CHAPTER OUTLINE - Find the cheapest test bank for your text book!

advertisement

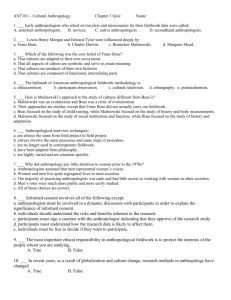

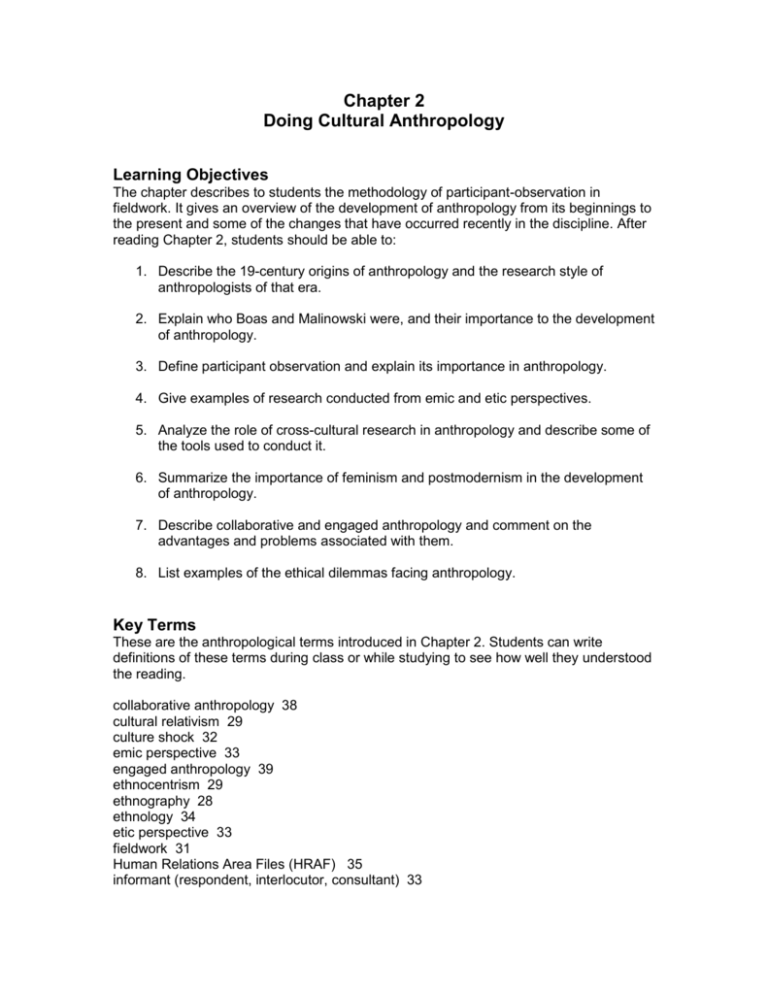

Chapter 2 Doing Cultural Anthropology Learning Objectives The chapter describes to students the methodology of participant-observation in fieldwork. It gives an overview of the development of anthropology from its beginnings to the present and some of the changes that have occurred recently in the discipline. After reading Chapter 2, students should be able to: 1. Describe the 19-century origins of anthropology and the research style of anthropologists of that era. 2. Explain who Boas and Malinowski were, and their importance to the development of anthropology. 3. Define participant observation and explain its importance in anthropology. 4. Give examples of research conducted from emic and etic perspectives. 5. Analyze the role of cross-cultural research in anthropology and describe some of the tools used to conduct it. 6. Summarize the importance of feminism and postmodernism in the development of anthropology. 7. Describe collaborative and engaged anthropology and comment on the advantages and problems associated with them. 8. List examples of the ethical dilemmas facing anthropology. Key Terms These are the anthropological terms introduced in Chapter 2. Students can write definitions of these terms during class or while studying to see how well they understood the reading. collaborative anthropology 38 cultural relativism 29 culture shock 32 emic perspective 33 engaged anthropology 39 ethnocentrism 29 ethnography 28 ethnology 34 etic perspective 33 fieldwork 31 Human Relations Area Files (HRAF) 35 informant (respondent, interlocutor, consultant) 33 Chapter 2 informed consent 43 institutional review board (IRB) 31 native anthropologist 42 participant observation 31 postmodernism 38 Lecture Outline I. Ethnography in Historical Perspective A. Ethnography is the gathering and interpretation of information based on intensive, firsthand study of a particular culture or the written report of this study. 1. Used as a basis for cross-cultural comparisons. 2. Data are analyzed to build and test hypotheses about cultural processes. B. Anthropology began in the late 19th century as a comparative science. 1. Early anthropologists, such as Lewis Henry Morgan and Sir Edward Burnett Tylor, were called “armchair anthropologists” because they did not practice fieldwork. 2. Anthropologists placed cultures they encountered on evolutionary scales of cultural development. a) These scales were characterized by different stages of technology or social institutions. b) Europeans were placed on the pinnacle of evolutionary success as “civilization,” while others were viewed as earlier forms of its development. 3. There were numerous problems with this kind of approach: a) Explorers and colonial officials exaggerated differences with Europe to promote colonialism. b) Many times these so-called “primitive” societies were actually colonial byproducts themselves, not “living fossils.” c) Evolutionists acknowledged that their “scales of achievement” were not well-established. C. By the early 20th century, fieldwork and ethnography had become the hallmarks of cultural anthropology. 1. Franz Boas was a primary influence in American anthropology. He: a) Rejected theories of evolution that held that some societies were more evolved than others. b) Developed the method of participant observation in fieldwork: (1) Living with natives while observing them. (2) Systematic recording of cultural patterns. (3) Use of archaeology and historical archives. (4) Collection of statistical data. c) Promoted theoretical ideas that cultures are products of their histories and that all human beings have equal capacities for culture. d) Insisted that anthropologists free themselves as much as possible from ethnocentrism, while cultivating cultural Chapter 2 II. relativism—understanding a culture from a native point of view. e) Tirelessly promoted human rights and justice. 2. In Britain, there developed a separate fieldwork tradition in large part due to the influence of Alfred Cort Haddon’s work in the Torres Straits. a) His study was interdisciplinary. b) Torres Straits prepared future ethnographers, such as Bronislaw Malinowski. (1) Malinowski’s main goal for an ethnographer was to obtain the native’s point of view by living among the native people. He: (a) Carried out fieldwork in the Trobriand Islands of Papua, New Guinea. (b) Argued that only through first-hand fieldwork could an anthropologist truly understand a member of another culture. (2) He developed an ethnography centered on empathic understanding of natives through description of social institutions and cultural and psychological functions. 3. Malinowski and Boas each had a distinct approach to anthropology. a) Boas focused on understanding cultures with respect to their context and histories. b) Malinowski emphasized the notion of function in the maintenance and stability of society 4. Malinowski and Boas also shared a common way of approaching cultures. Both: a) Developed strong fieldwork traditions of participant observation. b) Publicly and scientifically opposed racism. c) Agreed that all cultures are equally rational and none is superior to another. Anthropological techniques of fieldwork—the firsthand, systematic exploration of a society. A. Participant-observation is the fieldwork technique that involves gathering cultural data by observing people’s behavior and participating in their lives. It involves: 1. Gathering as much information as possible about a particular culture. 2. Observing, listening to, and asking questions of the natives studied. 3. Participant observation has advantages and limitations. a) Anthropologists are on the job 24 hours a day and observe people in all kinds of situations. b) However, they must work with small numbers of individuals. 4. Fieldwork is often funded and many times requires oversight by institutional review boards (IRBs)—university committees that oversee research of human subjects. Doing Cultural Anthropology 5. III. In the past, anthropologists frequently did studies of one small, relatively isolated group, but today they often focus on specific situations, individuals, or culture change. B. Participant observation involves challenges and styles. 1. Culture shock is feelings of alienation and helplessness that emerge when one is immersed in a new and different culture. 2. Variation of research styles includes: a) Emic perspective—seeking to understand a society from the inside. b) Etic perspective—using a scientific analysis as an outsider. c) Anthropological research often follows a natural science model: (1) Proposing a hypothesis. (2) Collecting empirical data. d) Highly interpretive style of anthropological research which uses techniques drawn from study of history and literature. C. When practicing participant observation, anthropologists utilize informants (consultants)—people who guide them and inform them of the native culture. Working with consultants is often informal, but may include: 1. Interviews. 2. Inventories and questionnaires. 3. Collection of genealogies. D. Other field techniques may include: 1. Photography and filming. 2. Mapping space. 3. Serving apprenticeships. E. Part of ethnographic fieldwork is also organizing and analyzing data. Ethnographic Data and Cross-Cultural Comparison A. Cross-cultural comparison has always been part of anthropology. 1. Boas and his students had the goal of encouraging Europeans and Americans to compare their own societies with those that anthropologists studied. 2. British and European anthropologists focused on ethnology—the attempt to find general principles or laws that govern cultural phenomena: a) Herbert Spencer developed a systematic approach to data called Descriptive Sociology. b) Americans George Murdock and Albert Keller created the Human Relations Area Files (HRAF) – a large, indexed ethnographic database. (1) This includes a wide range of current and historical societies. (2) It allows for insightful, creative comparisons across cultures. (3) It does have critics, though: (a) Reports are written from different perspectives. (b) Indexing is often inconsistent. Chapter 2 3. IV. There has also been single investigator cross-cultural research. a) Studies of violence. b) Medical research studies. c) Pre-school research. Changing directions in ethnography A. Feminist Anthropology 1. Questioning the power of gender bias in both ethnography and cultural theory has been a significant contribution. a) Historically, men who had limited access to women’s lives performed much of the fieldwork. b) Traditionally, it was assumed that men performed the most important cultural activities. c) By only presenting the male view, culture appears to be more homogeneous than it really is and may perpetuate the oppression of women by ignoring their own perspectives. 2. Increasing numbers of women faculty on university campuses have begun shifting this bias from male-centered studies to studies of both genders. B. Postmodernism is a theoretical perspective focusing on issues of power and voice. It suggests that anthropological accounts are partial truths reflecting on the background, training, and social position of their authors. 1. Ethnographers today are more sensitive to how their own status, personality, and cultural backgrounds can affect their interpretations and representations of a culture. 2. Ethnographies are “stories” and the ethnographer’s voice should be included with many other possible representations. 3. Works such as Orientalism by Edward Said encouraged anthropologists to think about the ways that they impact the data that is being collected. 4. Depending on their theoretical persuasions, anthropologists have differing views of postmodernism, but regardless of the anthropologist’s view, almost all contemporary ethnographies include some reflection about fieldwork conditions. C. Engaged and collaborative anthropology 1. Collaborative anthropology places the ethical responsibility to consultants above everything else. It seeks: a) To give priority to informants on the topic, methodology, and written results of research. b) To displace the anthropologist as the sole author representing the culture of a group. 2. Engaged anthropology moves from the production of texts to political action. It strives: a) To provide ethnographic data that will lead others to understand and help the community. b) To improve the life chances of individuals in the study community (see Bourgois’s study on p. 36-37 and LyonCallo’s study p. 39-40). 3. Engaged and collaborative anthropology generates some criticism. Doing Cultural Anthropology a) V. There is a tension between always producing what the informant desires and the scientific goal of not falsifying information. b) Native communities rarely speak in a homogenous, single voice, making multiple voices difficult to accurately record. D. Native Anthropology/native anthropologist conduct fieldwork in the anthropologist’s own culture. 1. Native anthropologists must try to maintain the social distance of an outsider because it is too easy to take for granted what one knows. a) Fieldwork of one’s own culture allows one a glimpse of the possible future (see Myerhoff’s study, p. 42). b) Cultural insiders may not have access to all people due to gender and social class distinctions. c) Anthropologists can examine their own culture objectively and bring what they learned back home again (see Jones’s study p. 42). 2. In recent years, native anthropology has become increasingly common. Ethical considerations in fieldwork A. Anthropologists must obtain informed consent of the people to be studied, protecting them from risk and respecting their privacy and dignity. B. In trying to address these issues, the American Anthropological Association Statement of Ethics holds anthropologists responsible for: 1. The people they study and those with whom they work. 2. Obligations to the discipline of anthropology: a) Not to endanger the research prospects of other anthropologists b) Publish the results of the research for the public and future researchers. 3. Obligations to sponsors. 4. Obligations to their own and host governments. 5. Obligations to the public. C. Numerous projects have tested the boundaries of the ethical considerations. 1. Project Camelot was controversial because it involved anthropologists in working for the foreign policy goals of the United States. a) What is the integrity of this research? b) How can the anthropologist be kept safe while in the field? c) For what purposes will this research be used? 2. It was because of Project Camelot that the American Anthropological Association first issued a statement on anthropological ethics. 3. Today, there are concerns about the engagement of some anthropologists with the American military. a) Some anthropologists work on military bases and at facilities providing anthropological training and analysis for officers. Chapter 2 Other anthropologists work “on the ground” collecting data in zones of active combat. (1) This is most controversial, as it is difficult to keep ethical obligations under these conditions. (2) Anthropologists have virtually no ability to safeguard any of their information under these conditions. 4. The majority of anthropologists oppose this use of anthropology. New Roles for the Ethnographer A. Immigration, expanded communication, and cheap transportation have all altered the nature of anthropology. 1. Traditional research sites are expended in size today and may include work across continents, even. 2. Fieldwork techniques have changed and now include more questionnaires, archival research, government documents, and court records. 3. Today, research is constantly being re-evaluated to reflect more global issues and connections. a) There may be a struggle over whose voice prevails in ethnography, as informants read and, increasingly, critique anthropological research. b) On the other hand, as natives’ knowledge has increased about the world around them, relations between anthropologists and natives have become closer and ethnographies more accurate. 4. In societies like Toraja of Indonesia, anthropological data and anthropologists may be incorporated as important sources of cultural authority. a) As aristocrats became more insecure about the relevance of their own royal genealogies, anthropological accounts became an important resource, shoring up their claims to noble status. b) Anthropological data becomes particularly relevant in societies who find traditional stratification is affected by the global economy. B. These forces of globalization have produced as much diversity as homogeneity. 1. New cultural forms are constantly being created. 2. Older cultural forms are undergoing constant adaptations. C. Anthropology is increasingly a rich field of study. b) VI. Student Activities and Assignments 1) Ask students to imagine they are doing ethnographic fieldwork: under what conditions do they think they would best work? What kinds of research would most interest them? Why? 2) Present various cases of ethical challenge and discuss possible actions that an anthropologist should or should not take under those conditions. The website for the American Anthropological Association has examples of ethically challenging Doing Cultural Anthropology fieldwork situations and discussions of how these might be addressed. See http://www.aaanet.org/profdev/ethics/ 3) Have students design a fieldwork manual, using step-by-step instructions on how to best prepare to go to the field to do research. They should create a proposal for research, a research design including methodology in the field, and a budget for the work. 4) eHRAF is available in many college/university libraries as an electronic resource. See if this is available on your campus and invite a librarian to class to present the mechanics on how to use this electronic source. Students should choose a cultural topic or topic area that interests them prior to the presentation and then work to compile e-resources available for doing this research. 5) If your university has a grants office and an IRB committee, ask students to do research on how the grants office works at your school. Get an IRB application and go through the steps of presenting a research proposal at your own campus. Many students, after their freshman year, will be able to use this information if they do any research, in any discipline, that involves human subjects. Media Suggestions (Films) 1) The Shackles of Tradition: Franz Boas. 1990. 52 minutes. (Pioneers of Anthropology: Strangers Abroad Series) A film by Bruce Dakowski and Andre Singer. Distributed by Films for the Humanities and Sciences, Princeton, NJ. Incredible account of the work of Franz Boas, whose fieldwork in the Arctic and the North West Coast of America gained him the title of the founding father of American anthropology. 2) Amchis: The Forgotten Healers of the Himalayas. 2001. 52 minutes. A film by Anoko Productions, ARTE, Pois Chiche Films. In this film about a small valley in the Himalayas, the traditions of healing and culture change are examined. Known as “amchis,” the traditional healers have become all-but-forgotten by younger generations of Tibetans who increasingly see Western remedies and more modern interactions. Located at the altitude of 3,700 meters, these remote villages are the last stronghold of traditional Tibetan medicine. (Internet Sites) 1) For an in-depth discussion of participant observation go to the website of Family Health International at http://www.fhi.org/NR/rdonlyres/ed2ruznpftevg34lxuftzjiho65asz7betpqigbbyorgg s6tetjic367v44baysyomnbdjkdtbsium/participantobservation1.pdf a. How is participant observation useful in applied anthropology? b. What are the strengths and weaknesses of participant observation? 2) The Royal Anthropological Institute has a fieldwork site with excellent video clips and follow-up web resources/useful information. See this at http://www.discoveranthropology.org.uk/about-anthropology/fieldwork.html