brainorgan

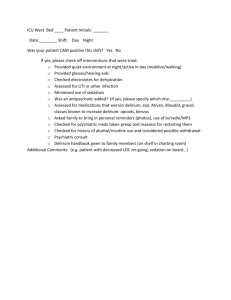

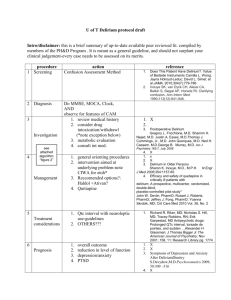

advertisement

REVIEW ARTICLE The Effects of Perioperative and Intensive Care Unit Sedation on Brain Organ Dysfunction Christopher G. Hughes, MD,* and Pratik P. Pandharipande, MD, MSCI*† February 10,2011. Increasing research and evidence, however, has implicated commonly prescribed sedative medications as risk factors for untoward events and worse patient outcomes, including brain organ dysfunction manifested as delirium and coma. The effect of sedatives on outcomes is also influenced by the depth of sedation, making it imperative to reduce total exposure to this class of medications. Juxtaposing the widespread necessity and use of sedation with the cost of acute and long-term cognitive dysfunction to patients and society, physicians must now strive to balance patients’ demands and requisite for comfort with their own oath to do no harm. Delirium is an acute disturbance of consciousness accompanied by inattention, disorganized thinking,and perceptual disturbances that fluctuates over a short period of time. Though previously underdiagnosed and often considered to be an inconsequential occurrence associated with a patient’s perioperative course or critical illness delirium is now regarded as a form of acute brain organ dysfunction that is independently associated with worse clinical outcomes, including longer and more costly hospitalizations, longer times on mechanical ventilation, increased rates of hospital readmissions, increased risk of prolonged cognitive dysfunction, and 3-fold higher mortality. Furthermore, each additional day with delirium increases the risk of dying by 10%, and longer periods of delirium are also associated with greater degrees of cognitive decline when patients are evaluated 1 year after hospital discharge. 50%–80% of patients with critical illness developing delirium depending on the severity of illness and the need for mechanical ventilation . Although delirium, along with coma, represents acute brain dysfunction, many surgical patients (with concurrent anesthesia exposure) and critically ill patients also have long-term cognitive impairment (chronic brain dysfunction), which may persist for months to years after their hospitalization, significantly impacting their quality of life. There are numerous hypotheses that include neurotransmitter imbalance (e.g., dopamine, γ-aminobutyricacid, and acetylcholine), inflammatory perturbations (e.g., tumor necrosis factorI, interleukin-1, and other cytokines/chemokines), impaired oxidative metabolism, cholinergic deficiency, and changes in various aminoacid precursors Contributing sources can be summarizedas patient-related actors (e.g., age, previous dementia,diabetes, and heart failure) or iatrogenic risk factors (e.g.,psychoactive medications, hypoxemia, shock, and hypothermia) SEDATIVE AND ANALGESIC MEDICATIONS AND ACUTE AND CHRONIC BRAIN DYSFUNCTION Numerous associations between psychoactive medications and worsening cognitive outcomes in postsurgical patients have been published. Insufficient pain relief, however, has also been shown to be a risk factor for delirium and can contribute to sleep disturbances, disorientation, anxiety,and long-term effects such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).26 Morrison et al.27 conducted a prospective cohort study that enrolled patients with hip fractures, none of whom had preoperative delirium. Patients who received <10 mg of parenteral morphine equivalents per day were more likely to develop delirium than were patients who received more analgesia.27 However, providing adequate analgesia needs to be balanced with the potential risk for predisposing patients to delirium due to excess opiate administration. Marcantonio et al.24 studied postoperative patients who developed delirium and found an association between benzodiazepine and meperidine use and the occurrence of delirium, and Dubois et al.22 have shown that opiates (morphine and meperidine) administered either IV or via an epidural route may be associated with the development of delirium in surgical patients. The role of perioperative benzodiazepine plasma levels has been further evaluated in a small study but found no relationship between diazepam concentration and cognitive dysfunction 1 week postoperatively in elderly patients undergoing abdominal surgery.28 Two large prospective studies have examined the effects of perioperative psychoactive medications on emergence delirium in the postanesthesia care unit. Lepouse et al.29 conducted a prospective study of 1359 consecutive patients who were evaluated for emergence delirium in the postanesthesia care unit. The authors found an incidence of emergence delirium of 4.7% and demonstrated an almost 2-fold increase in the odds of developing emergence delirium if benzodiazepines were administered as a preoperative medication. In the second study by Radtke et al. 301868 patients were evaluated in the recovery room and assessed for emergence delirium and hypoactive emergence.These authors found the incidence of emergence delirium to be 5% and that of hypoactive emergence to be 8%. Significant risk factors for emergence delirium were benzodiazepine premedication and etomidate induction,whereas longer anesthetic duration was a risk factor for hypoactive emergence.30 The International Study of Postoperative Cognitive Dysfunction evaluated patients for cognitive impairment after major noncardiac surgery and found that approximately 25% had cognitive impairment at 1 week postoperatively,10% at 3 months, and about 1% at 1 year.19,31 Although anesthetic duration was found to be a risk factor for early cognitive impairment, only age was a risk factor for cognitive impairment at 3 months.19 A follow-up May 2011 • Volume 112 • Number 5 study showed no difference in cognitive impairment at 1 week and 3 months in patients receiving regional anesthesia versus general anesthesia, though the group receiving general anesthesia had a slightly higher mortality.32The temporal association of psychoactive medications and delirium in critically ill patients has recently been studied in 3 separate cohorts.11,14,25 Pandharipande et al.25followed a cohort of mechanically ventilated medical ICU patients and found that lorazepam was an independent risk factor for daily development of delirium after adjusting for important covariates such as age, severity of illness, and presence of sepsis. Fentanyl, morphine, and propofol were associated with higher but not statistically significant odds ratios.25 Similar associations between midazolam and worse delirium outcomes have been found in trauma, surgical, and burn ICU patients.11,14 It is important to note that the data on opioids and brain dysfunction are not as consistent as are those with benzodiazepines. Although meperidine has been associated with delirium in most of the published studies, data with other opioids have been less convincing. In fact, some studies have suggested that morphine and thadone have beneficial effects with regards to delirium.11,14,24,27 Thus, it is possible that opioids are protective in patients at high risk for pain but may be detrimental if utilized to achieve sedation. DEPTH OF SEDATION AND OUTCOMES Although sedative and analgesic medications have a very important role in patient care,comfort, and safety, health care professionals must strive to achieve the right balanceof drug administration. Inadequately treated pain leads totachycardia, increased oxygen consumption, hypercoagulability,immunosuppression, hypermetabolism, and increased endogenous catecholamine activity.33,34 Additionally,hyperactive delirium or agitation can become life threatening if it leads to the removal of devices such as endotracheal tubes and intravascular lines, and unrelieved anxiety can be a significant source of physical and psychological stress for patients both during an acute event and in the long term, when PTSD may result.26 Similarly, intraoperative awareness has also been associated with persistent PTSD, attesting to the importance of adequate amnesia during general anesthesia.35,35a So how does this correlate with depth or choice of anesthesia? In theory, deeper levels of anesthesia (e.g.,decreased levels of responsiveness) and benzodiazepine use would decrease intraoperative awareness and PTSD.Results from the B-Aware Trial suggest that using the bispectral index (BIS) for titration of anesthesia in a population at high risk for awareness reduces the risk of recall.36 A study by Kerssens et al.37 examined the ability of patients to recall lists of words played during BIS-guided anesthesia and found that titration to BIS 50 to 60 did not necessarily offer any benefits. Farag et al.38 found that deeper levels of anesthesia according to the BIS were associated with improved cognitive function 4 to 6 weeks postoperatively,particularly with respect to the ability to process information. However, BIS levels <45 used as a surrogate for deep sedation have been associated with increased mortality at 1 year, 2 years, and even longer postoperatively.35,39,40 Monk et al.39 followed 1064 patients undergoing general anesthesia for major noncardiac surgery and found that cumulative deep hypnotic time (BIS <45) was an independent predictor of mortality at 1 year in addition to patients’ comorbid diseases and intraoperative hypotension. A followup study40 in 174 patients confirmed these findings and extended the association of low levels of BIS with mortality up to 2 years, but it cautioned that in comparison with the comorbid conditions, the contribution of depth of anesthesia was weak. Finally, the B-Aware trial35 found that absence of BIS values <40 for >5 minutes was associated with improved survival and reduced morbidity. Recently, Sieber et al.41 demonstrated that sedation during spinal anesthesia for hip surgery targeted towards higher BIS levels (e.g., lighter sedation and increased levels of responsiveness;BIS P80) decreased the incidence of postoperative delirium in elderly patients in comparison with patients sedated with propofol to a BIS of approximately 50. A Cochrane Database review suggested that regional anesthesia(and subsequent higher levels of consciousness in comparison with general anesthesia) may decrease postoperative confusion in hip surgery patients,42 but a more recent structured, evidence-based, clinical update suggested that there was no significant difference in the incidence of delirium or postoperative cognitive dysfunction when general anesthesia and regional anesthesia were compared.43 The ongoing dexamethasone, light anesthesia, and tight glucose control (DeLiT) trial will hopefully shed further light on the effects of intraoperative anesthesia and cognitive outcomes.44 Oversedation, however, occurs commonly in ICU patients and is associated with worse clinical outcomes,including longer time on mechanical ventilation and in the ICU, greater need for radiological evaluations of mental status, and higher probability of developing delirium.11,14,25,45,46 Furthermore, the presence of burst suppression on encephalograms, associated with deep sedation, has been shown to be an independent predictor of mortality in critically ill ICU patients.47 Instituting daily interruption of sedatives and analgesics, protocolizing their delivery, and instituting target-based sedation have all been shown to decrease sedative administration and improve patient outcomes, though many of these studies have not specifically evaluated delirium rates or duration. The Awakening and Breathing Controlled Trial 50 which combined daily spontaneous awakening and breathing trials, showed a 50% reduction in sedative use that was accompanied by a reduction in coma and ventilator days during the ICU stay and, more importantly, in mortality at 12 months. Notably, this linked approach was not associated with an increase in long-term neuropsychological outcomes, including PTSD, attesting to the fact that deep sedation and amnesia are not necessary in the majority of critically ill patients.52,53 In fact, sedatives (lorazepam in particular) have been associated with increased PTSD symptoms,54 and symptoms of depression and PTSD have been positively associated with more days of sedation in the ICU.55 Unpleasant memories of the ICU stay may contribute to PTSD symptoms in survivors,56–58 although data have shown that PTSD is more often related to having delusional memories of the ICU stay and that factual memories, even if painful, are less likely to cause PTSD.59,60 Similarly, patients who had recall of their ICU stay had less cognitive dysfunction than did patients with no recall of their ICU experience, further emphasizing that excessive sedation and amnesia may have prolonged neuropsychological and cognitive effects.61 Initiating physical therapy early during the patient’s ICU stay has also been associated with improved outcomes, including decreased length of stay both in the ICU and hospital.62 Taking this approach a step further, Schweickert et al.63 examined the effect of combining daily interruption of sedation with physical and occupational therapy on the development of ICU-acquired weakness and delirium in mechanically ventilated patients. They demonstrated that patients who underwent early mobilization had an approximate 50% decrease in the duration of delirium in the ICU and hospital and had significant improvement in functional status at hospital discharge.63 Therefore, a liberation and animation strategy (ABCDEs) focusing on Awakening and Breathing trials (AB), Choice of sedation (C), Delirium monitoring and management (D), and early Exercise (E) during critical illness can improve patient outcomes and likely reduce the incidence and duration of acute and long-term brain dysfunction in critically ill patients.64 CHANGING ICU SEDATION PARADIGMS TO IMPROVE PATIENT OUTCOMES Beyond target-based and goal-directed sedation with daily interruption of sedatives, the choice of sedative has implications on cognitive impairment. Studies comparing propofol with benzodiazepines have shown better outcomes in patients randomized to the propofol group May 2011 • Volume 112 • Number 5 in the majority of the investigations.65,66 Similarly, analgesiabased approaches towards sedation with the use of remifentanil have shown shorter times on mechanical ventilation, though we must be attentive to withdrawal and hyperalgesia if remifentanil is considered.67,68 The MENDS study (a randomized controlled trial of the I2 agonist dexmedetomidine versus lorazepam) provided evidence that sedation with dexmedetomidine can decrease the duration of brain organ dysfunction, with less likelihood of delirium development on subsequent days.69,70 The SEDCOM study compared dexmedetomidine with midazolam and demonstrated a reduction in delirium prevalence with dexmedetomidine along with a shorter time on mechanical ventilation.71 Another recent randomized controlled trial, the DEXCOM study, compared dexmedetomidine with morphine and showed that dexmedetomidine reduced the duration but not the incidence of delirium after cardiac surgery in comparison with morphine-based therapy.72 These studies attest to the fact that reducing benzodiazepine exposure by using alternative sedation paradigms improves patient outcomes, including brain dysfunction. Extrapolation of these data to the operating room environment is challenging; ongoing clinical trials will hopefully answer important questions with regards to the benefits and risks of preoperative anxiolysis therapy and the practice of sedative administration while undergoing surgical procedures under regional anesthesia. DELIRIUM AND COGNITIVE DYSFUNCTION PREVENTION The most important factor in preventing and managing delirium is to recognize and proactively treat reversible causes of delirium. These include, but are not limited to, pain, anxiety, sleep disturbances, hypoxia, hypercarbia, hypoglycemia, metabolic derangements, shock, and medication effects. Beyond that, just as the potential causes of delirium are multifactorial, the approach to prevention must be multifaceted. A landmark study of medical patients reduced the development of delirium by 40% by focusing on several key goals, including regular provision of stimulating activities, a nonpharmacological sleep protocol, early mobilization activities, appropriate and early removal of catheters and restraints, optimization of sensory input, and attention to hydration.73 Similar studies have shown a decrease in the duration and severity of delirium without impacting overall incidence;74,75 others have shown benefit only in subgroups of patients76 or have not shown any benefit at all.77Unfortunately, there are few data about the efficacy of these strategies in perioperative and ICU patients. As was mentioned earlier, a strategy focusing on reducing sedative drug exposure via coordination of ABCDEs may reduce the incidence and duration of acute and long-term brain dysfunction in critically ill patients.64 DELIRIUM MANAGEMENT Pharmacologic therapy to manage delirium should be attempted only after correcting any contributing factors or underlying physiologic abnormalities. Numerous studies have examined the effects of antipsychotic medications on delirium, though large randomized controlled trials comparing the efficacy of typical and atypical antipsychotics to placebo are still lacking. Contributing sources can be summarizedas patient-related factors (e.g., age, previous dementia,diabetes, and heart failure) or iatrogenic risk factors (e.g.,psychoactive medications, hypoxemia, shock, and hypothermia) In one of the first studies in critically ill patients, olanzapine and haloperidol were shown to be equally effective in reducing the severity of delirium symptoms.In a small study of patients with delirium and with orders to receive as needed haloperidol,quetiapine was shown to be more effective than placebo in time to resolution of delirium. Prakanrattana et al. conducted a randomized controlled trial and showed that a single dose of risperidone sublingually after cardiac surgery reduced the incidence of delirium in comparison with placebo. Rivastigmine has been recently studied as an adjunct to haloperidol and was not found to decrease the duration of delirium while potentially contributing to increased mortality. Additionally, there are now data showing that dexmedetomidine reduced the time to tracheal extubation, decreased ICU length of stay, and decreased the incidence of tracheostomy in comparison with haloperidol in critically ill patients with agitated delirium. Although drugs used to treat delirium are intended to improve cognition, there is an important caveat in that they all have psychoactive effects that may further cloud the sensorium and promote a longer overall duration of cognitive impairment. Delirium is a prevalent and costly problem that is associated with significant morbidity and mortality in our patient population. On the basis of the available literature reviewed in this article, anesthesiologists can significantly decrease the burden of this acute brain dysfunction given our active roles in operating room and ICU patient care. Management techniques with an integrated approach that includes alteration of sedative medication regimens, deployment of preventative strategies, initiation of delirium monitoring, and judicious use of pharmacologic therapy can reduce the incidence and impact of this disease and, plausibly, chronic brain dysfunction as well.