File - Anne W. Anderson

advertisement

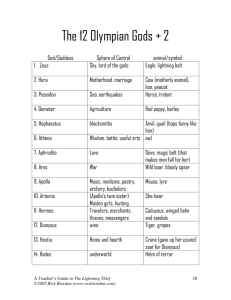

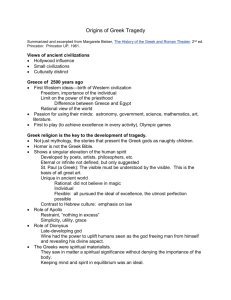

RUNNING HEAD: BUSTING OPEN WATERBUSTERS Busting Open Waterbusters: Finding Meaning within the Visual, Aural, and Choreographical Layers of an Imagined World Anne W. Anderson University of South Florida Patriann Smith University of Illinois Jenifer Jasinski Schneider University of South Florida 1 BUSTING OPEN WATERBUSTERS 2 Abstract As the percentage of the world’s population linked to the Internet—even in areas traditionally termed underdeveloped—grows at exponential rates, the digital divide rapidly is shrinking, and classroom teachers find themselves teaching digital methods of expression to children of many ages. Evaluating digital works, which may contain layers of multi-modal texts, challenges teachers and others to consider each layer separately and in relation to the others. Such evaluations also raise the philosophical questions, debated through the ages, of what constitutes art, what constitutes meaning, and whether art and meaning are to be found in the process or in the end product. This paper examines these evaluative and philosophical questions in terms of the dichotomy between the Greek gods Apollo and Dionysus, by applying Rodriguez and Dimitrova’s four-tiered model of evaluation multi-modal texts and Eco’s discussion of ostention to “Waterbusters,” a video produced at by 6th grade students from a public charter school under the direction of preservice teachers, supervised by a faculty member, at a nearby university. Additionally, we theatricize the data and embody the dichotomy as a dialogue between Apollo and Dionysus, moderated by their father, Zeus. BUSTING OPEN WATERBUSTERS 3 Busting Open Waterbusters: Finding Meaning within the Visual, Aural, and Choreographical Layers of an Imagined World As the percentage of the world’s population linked to the Internet—even in areas traditionally termed underdeveloped—grows at exponential rates, the digital divide rapidly is shrinking, and classroom teachers find themselves using and teaching digital methods of expression to children of many ages. Evaluating digital works, which may contain layers of multi-modal texts, challenges teachers and others to consider each layer separately and in relation to the others. Such evaluations also raise the philosophical questions, debated through the ages, of what constitutes art, what constitutes meaning, and whether art and meaning are to be found in the process or in the end product. Athanases (2008) described this divide in terms of the dichotomy between the Greek gods Apollo—“god of theory, of clear and rational understanding” and “linked to the static arts of sculpture and architecture and of distanced introspection and repose”—and Dionysus—“god of dynamic arts such as drama, music, song, and dance; of art as life in process” (p. 119). Callois (1958/2001) termed the divide as one between “ludus: play as a rule-governed system” and “paidea: a looser, more chaotic form of play” (as cited in Burns, 2009, p. 158), considering play in the commonly accepted metaphor that life is a game we can either play by the established rules (evoking the Apollonion or luddite) or ignore to our peril or to heightened levels of creativity (evoking the Dionysian or paidean). Applying these analogies to the questions of evaluating children’s digital work and of determining whether the work has artistic value— suggesting elements of imaginative thought—and/or conveys meaning—suggesting elements of rational thought—raises further questions of who establishes the rules for producing such work, BUSTING OPEN WATERBUSTERS 4 who establishes the standards by which such works are evaluated, and whether it is the final, static product or the fluid process leading to the product which ought to be examined. We bring these ethereal, philosophical questions down to earth by applying them to a specific product, a video produced by 6th grade students from a public charter school. The video, “Waterbusters,” was one of several videos produced by teams of students, guided by preservice teachers who were themselves students in a writing/composition methods course taught by one of the authors, a faculty member at a major university (Schneider, in press). Each video focused on a different environmental issue in the College of Education, and all videos were submitted as part of a university-wide grant-writing project on sustainability. The written application included a 65-page report (Schneider, 2011) consisting of an introduction of the project, an overview of the teaching timeline and introduction of the staff involved, a section describing the ways in which the project was presented and in which skills were taught to the pre-service teachers and to the students, and detailed explanations of each project, including line-itemed budgets developed by the children. The overall theme of the project was “Going Green to Save Gold,” a word-play on the university’s school colors. This particular group of five students focused on the problem of broken sprinkler heads wasting water and, by extension, money. The grant application was not funded, but the material produced—both the videos and the written report—provided much data for further analysis. Subsequently, the other two researchers, doctoral students studying multi-modal and multi-mediated literacies under the direction of the same faculty member who had created the video project, sought to discover the meanings implicit in the students’ uses of different modalities and to consider the collective impact of this multi-modal, multimedia text. Chandler-Olcott (2008) said “semiotic activity is about selecting which modes (e.g., spatial, visual, audio, gestural, and/or linguistic) need to be emphasized in a BUSTING OPEN WATERBUSTERS 5 particular context to achieve a particular end” (p. 251). More than just selecting modes and then deciding when, where, and how to emphasize one or more modes, the goal of a multimedia project, as Kress and Van Leeuwen (2001) noted), is to combine the modalities to create “an entire semiotic product or event” (as cited in Chandler-Olcott, 2008, p. 251). In a sense, the combination of modes to convey a message can be said to be analogous to the fable of the bundle of sticks being stronger than its individual component parts. Methods of analyzing the sticks and the bundle But how to analyze the sticks and the bundle? We turned to Rodriguez and Dimitrova’s (2011) “four-tiered model of identifying and visualizing frames” (p. 48) to guide our process of evaluating the video. At the first level, the denotative level of interpreting visual elements, we described and accepted at more or less face value what we saw in the product. At the second stylistic level, we noted the choices made by the videographers, sound editors, costumers, prop managers, actors, and others involved in the process of creating the video. Connotatively, the third level of Rodriguez and Dimitrova’s model, we interpreted symbolically what was presented in each scene. Finally, we discussed the ideological representations conveyed by the product as a whole. We completed this process separately, compared our findings at a later time and considered the implications of the similarities and differences we each found. In this paper, then, we explore the multi-modal aspects of the video, consider the interstitial spaces as related to the video’s possible meanings—considering also the product-within-a-product aspect of the video in relation to both the writing methods course and the grant application—then discuss how future research might address other questions raised by the exploration. Additionally, we embody the dichotomy as a dialogue between Apollo and Dionysus, moderated by their father, Zeus, with commentary provided by a Chorus. BUSTING OPEN WATERBUSTERS 6 How we applied Rodriguez and Dimitrova’s (2011) four-tiered model. Anne and Patriann were students in a graduate-level multimedia literacies course taught by Jenifer, an associate professor in Childhood Education and Literacy Studies. The year prior to this course, Jenifer had taught an undergraduate teaching writing/composition methods course to preservice teachers. These preservice teachers worked with groups of 6th grade students from a nearby public charter school to produce short public-service announcement type videos about an environmental issue. These videos became part of a sustainability grant proposal submitted to the university. In the multimedia literacies course, Jenifer directed the graduate students, including Patriann and Anne, to view the videos (along with another group of student-produced videos that focused on social studies and science content) and to evaluate and analyze them. The instructions for the first four weeks were the same: Borrow concepts and strategies from the readings to analyze some aspect of these texts. You may analyze within one sample or across several. The focus of the analysis and the selection of text(s) is up to you, but…show clear evidence that you have applied or reappropriated concepts and strategies from the readings. Discuss your process and results…. [Examples of aspects to consider] Text, images, movement, sound, camera shots, as well as text embedded within these multimodal texts, etc. For each one of the previous [aspects listed], you can analyze themes, linguistics, classroom discourse analysis, technical production, etc. (Schneider, 2012) On the fifth week, Jenifer pointed out that “rather than looking solely at images, or movement, or text, the authors [of our readings] examine the interstitial spaces,” and she instructed us to “analyze your selected text in light of the authors' claims that resonate most with you. Maybe you can try something that doesn't resonate too” (Schneider, 2012). On the sixth and last week, Jenifer instructed us to look beyond the readings, to consider the video as part of a larger body of literature, and to consider what questions had not been asked or answered. BUSTING OPEN WATERBUSTERS 7 Coincidentally, Anne and Patriann each chose the same video, “Waterbusters,” to analyze, and each gravitated, separately, to Rodriguez and Dimitrova’s (2011) four-tiered, systematic model of considering the video at different levels, albeit to differing degrees. Additionally, as Anne discovered, the model lent itself to other applications, and she applied the same method of discovery to considering the aural and choreographical layers of the video. Tables 1 and 2 illustrate the paths of discovery each took in analyzing the video. Combining voices and dramatizing the data. When Jenifer suggested we compare notes and consider co-writing an article about our process of analyzing a student-generated video composition, we were intrigued; but, from having been in previous courses together, we knew we had very different writing styles and voices. Additionally, while Patriann had written about the entire video, Anne had focused more closely on just the three opening scenes. We wondered how we would blend our voices and our data. However, Anne had taken two courses in the spring and summer that considered the use of drama and narrative as a means of inquiry, one of which was taught by Jenifer, and had read a number of articles about methods of dramatizing data, usually as an ethnographic exploration called ethno-theater or performance ethnography. Bird (2011), for instance, studied the processes of four drama educators as they created performance drama based on the experiences of female students at a major university, and Carter (2010) discussed the use of monologue as a means of teacher reflection. Similarly, White and Belliveau (2011) explored the additional insights gleaned when theatricalized dialogues between educators and artists were performed in front of varying types of audiences. Anderson’s (2007) discussed experiences with performance ethnography using verbatim interview data, usually collected from individuals who are part of marginalized groups of people, as scripted texts. Kazubowski-Houston (2012) guided aging Roma women in Poland to share, via non-public BUSTING OPEN WATERBUSTERS 8 dramatic storytelling sessions, their experiences with each other, while Greenwood and McCammon (2007) used process drama and the story of the three billy goats, a bridge, and a troll to explore the third space between cultures in a cross-cultural workshop in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Schneider, King, Kozdras, Minick, and Welsh (2011) scripted and performed a play based on their own experiences guiding preservice teachers as they worked with elementary-age students at a multi-media writing/composing camp. Gray (2009) described using theatre artists and health researchers to develop a performance about traumatic brain injury. In our own case, we wondered if our disparate voices lent themselves to a dramatized dialogue and if narrative inquiry could be applied to a theatricized reading of our data. We recalled Athanases’ (2008) discussion of the Apollonian and the Dionysian approaches to meaning and wondered if, instead of speaking verbatim in our own voices from our separate analyses, we could assume the characters of Apollo and Dionysus and combine our thoughts to explore oppositional perspectives about evaluating product vs. process, aesthetic meaning vs. pragmatic meaning, and child-produced (immature) artifacts vs. adult-produced (mature) artifacts. Saldaña’s (2003) descriptions of ethnotheatre (combining the arenas of “formal theatre production” and “research participants’ experiences and / or researchers’ interpretations of data for an audience” [p. 218]), ethnodrama, (a script created from “analyzed and dramatized significant selections from…[various] written artifacts” [p. 218]), and characters (“research participants portrayed by actors” or by “the researchers and participants themselves” [p. 218]) spoke to the concept but did not address the researchers’ assuming characters other than themselves or anyone else directly involved in the production of the videos or of the analytic process. However, Saldaña (2003) did discuss the “appropriateness of a story’s medium” (p. 219) BUSTING OPEN WATERBUSTERS 9 and noted that playwrights have been “representing social life on stage” (pp. 230-231) for more than two millennia. While we were exploring conceptual ideas more than social life—we were not, for instance, dramatizing the interaction among the group producing the video nor our own process of viewing the data—we saw social life as replete with conceptual ideas. In this sense, then, we decided to proceed with our experiment of dramatizing the data through voices other than our own, but we remained reluctant to term this ethnotheatre. Additionally, in theatricizing the data, we selected some portions and omitted other, equally interesting, equally valuable data in order to fit the presentation within the time constraints of a public performance at a conference, and the question of framing data remained foremost in our wondering about this form of inquiry. Nevertheless, Anne developed, over two iterations, the following script: Live! From Mount Olympus: “Busting Open Waterbusters: Finding Meaning within the Visual, Aural, and Choreographical Layers of an Imagined World” Characters: Zeus: Father of gods and men, god of the sky and of the heavens, brother to Poseidon (god of the sea) and Pluto (god of the underworld); married to his sister Hera, but many times unfaithful to her; Zeus “upheld law, justice and morals, and this made him the spiritual leader of both gods and men” (Zeus, 2005, ¶1). Wonder what Hera thought of that…. Apollo: Zeus’s son by Leto, one of the Titans; twin to Artemis; associated with the sun and light, Apollo was the god of music, “prophecy, colonization, medicine, archery (but not for war or hunting), poetry, dance, intellectual inquiry and the carer of herds and flocks” (Apollo, 2004, ¶1). Apollo’s list of approved dances included, no doubt, the stately quadrille. Dionysus: Zeus’s son by Semele, a mortal; called by the Romans ‘Bacchus,’ Dionysus is the “god of wine, agriculture, and fertility of nature, who is also the patron god of the Greek stage” (Dionysus, 2007, ¶1), or what we today might call one wild and crazy guy. Chorus: Weiner (1980) discussed of the Chorus as the song-and-dance backdrop of the theatrical action, but he also noted that Sophocles won a number of play-writing competitions by integrating the Chorus “into the fabric of the play” until it “resembles a ‘collective character’” (p. 206). The Chorus as an “element of production” adds “to the general pleasure and understanding of the audience” (p. 210), and our Chorus does just that! BUSTING OPEN WATERBUSTERS 10 Props: Throughout, the CHORUS holds a Tragedy/Comedy mask on a stick. Slides are projected throughout. Setting: The scene takes place on the lofty heights of Mount Olympus, where the gods dwell between heaven and earth. (As the scene begins, RESEARCHERS 1, 2, and 3 (ZEUS, APOLLO, and DIONYSUS) sit at the conference table. The CHORUS stands, faces the audience, and raises her masks. SLIDE: Title Slide1) CHORUS: (addressing the audience) Hail, mortal audience! Greetings in the name of Zeus, and (gestures to indicate the performance space) welcome to Mount Olympus, where the gods observe and comment on mortal lives. Today, mortal researchers Jenifer Schneider (RESEARCHER 1 / ZEUS stands, dons costume, and looks down at an unseen earthly scene), Patriann Smith (RESEARCHER 2 / APOLLO stands, faces away from audience on one side of ZEUS, and dons costume), and Anne Anderson (RESEARCHER 3 / DIONYSUS stands, faces away from audience on the other side of ZEUS, and dons costume) assume the roles of ZEUS (gestures to ZEUS: SLIDE: Theory & Theatre2) and his two sons—by different women—APOLLO (gestures to APOLLO), “god of theory...linked to the static arts,” and DIONYSUS (gestures to DIONYSUS), called Bacchus by the Romans and considered the “god of dynamic arts [such as theatre]...of art as life in process” (Athanases, 2008, p. 119). (Beat) One day, Zeus, looking down from Mount Olympus, saw a group of 6th grade students working with a pre-service teacher, under the direction of a university faculty member, to create a video as part of a writing methods course. He called Apollo and Dionysus into his presence. (APOLLO and DIONYSUS turn to face audience, step forward, and stand on either side of ZEUS) ZEUS. (gestures below) My sons, mortal children are staging scenes and creating a video, “Waterbusters.” (SLIDE: Waterbusters3) The students intend to focus attention on the problem of broken sprinkler heads, at a university campus, wasting water and, by extension, money. Is this art? Is this information? What do you suppose this means? APOLLO. (disdainfully) What possible meaning could be contained in something made by children? Didn’t one of these mortals, Vygotsky, write that “a lack of technical skill prevents [children’s] creations, no matter how meaningful to their personality development, from reaching artistic status” (as cited in Smagorinsky, 2011, p. 325)? Slide: Title Slide shows the playbill logo, title, and researchers’ names / affiliations Slide: Theory & Theatre includes this text: Greek word thea means view / Theory and Theatre (Athanases, 2008, p. 119) 3 Slide: Waterbusters shows beginning frame of video 1 2 BUSTING OPEN WATERBUSTERS 11 DIONYSUS. (enthusiastically) Children? Staged scenes? Video? Fantastic! Young “world builders,” Figueiredo (2011), another mortal thinker, might call them--”creating meaning from fragments of data” (p. 92). Sight, sound, lights, camera, action! What a fluidly artistic and divine process! APOLLO. Can a video of staged scenes even be classified as art? Sculpture, architecture, even painting are static--one can ponder and reflect on their meaning. But video produced by children? It’s not stable! Everything’s going on at once! It’s so...messy! Let us consider this rationally, O Zeus. First, what do you mean when you ask what this means? Do you refer to the meaning contained in the product of the video itself? DIONYSUS. Or to the meaning derived during the process of creating the video? APOLLO. That’s not meaning! Meaning only exists in a product. (CHORUS shakes head and makes an “Oh, please—not in front of our guests” sort of gesture during this next exchange) DIONYSUS. Process! APOLLO. Product! DIONYSUS. Process! ZEUS. Silence! This cannot and will not be decided by bickering. (Beat) You will use mortal means to explore the multi-modal aspects of the mortally-produced video. You will view the text in four iterations (SLIDE: Levels of Visual Framing4), using other mortal work by Rodriguez and Dimitrova (2011). CHORUS. (without emotion) Denotative. (Beat) Stylistic. (Beat) Connotative. (Beat) Ideological. (faster) Denotative. Stylistic. Connotative. Ideological. (cheering enthusiastically and waving masks) Denotative, Stylistic, Connotative, Ideological—Go-o-oo-o, gods!!! (notices audience, stops, and composes self) (SLIDE(S): Theory5) 4 Slide: Levels of Visual Framing lists citation for Rodriguez & Dimitrova (2011) and four pairs of words: Denotative / Literal, Stylistic / Techniques, Connotative / Symbolic, Ideological / Critical 5 Slide(s): Theory includes these texts: (1) “[M]ultimodal texts require different cognitive strategies from written texts because the meaning in visual images is derived from spatial relations whereas the meaning in written text emanates from its temporal sequence” (Serafini, 2011, p. 343) and (2) “Semiotic activity is about selecting which modes (e.g., spatial, visual, audio, gestural, and/or linguistic) need to be emphasized in a particular context to achieve a particular end” (Chandler-Olcott, 2008, p. 251), and (3) The goal of a multimedia project is to BUSTING OPEN WATERBUSTERS 12 APOLLO and DIONYSIS. (Eagerly) Agreed. (both open their mouths as if to say something, but ZEUS beats them to it) Zeus: And we will cast lots to determine who speaks first. (mimes taking a token from each son, shaking them together, closing his eyes, and drawing one) Apollo, you shall speak first. (APOLLO begins to smirk) Dionysus, you shall have the last word. (DIONYSUS smirks) APOLLO and DIONYSUS. (Less eagerly than before) Agreed. ZEUS. Let us view a portion of the video. (SLIDE: Waterbusters6) (ZEUS sits and assumes the role of moderator) ZEUS. Proceed. APOLLO. (Imperiously) Considering visuals as denotative and stylistic-semiotic systems allows for examination of images through identification of the objects and elements observed in the visual, followed by the organization of these into themes based upon certain principles of organization (Rodriguez & Dimitrova, 2011, p. 53). We begin, therefore, with the (with a touch of disdain) stage. (Beat) Let it be known that, despite my disdain for their artistic value, I can speak to the “fluid arts” as well as my brother. (DIONYSUS gestures “Oh, brother” and becomes increasingly bored, looks at imaginary watch, etc.) As Honzl (1940/1998) noted, “although a stage is usually a construction, it is not its constructional nature that makes it a stage but the fact that it represents dramatic place” (p. 270). So, for the first actor, the bench (CHORUS becomes game-show model and indicates bench in SLIDE) on which he sits becomes a stage, while for the second and third, the steps (CHORUS indicates steps) and sidewalk (CHORUS indicates sidewalk) on which they move assume a stage-like quality. In Honzl’s (1940/1998) words, a “stage could arise anywhere—any place could lend itself to theatrical fantasy” (p. 271). (SLIDE. Still Images / Opening Scene7) DIONYSUS. (exaggeratedly polite) My brother fails to note the stages he describes are static objects, the sculptures, if you will, of which he so highly speaks and on which mortal creatures play their parts. (Beat) (CHORUS indicates various items as they are mentioned) The opening scene fades in from a blur to a scene of a person, (becoming more effusive) wearing sneakers, green shorts, a white t-shirt, and a bright green wig!—love it!—sitting outdoors on a bench, head tilted back and resting on the back of the bench. The sound effect of a loud snore tells us the person is sleeping, and a subtitle proclaims, “One day at the College of Education…” all of which lead us to assume the person is a student. combine modalities to create “an entire semiotic product or event (Kress and van Leeuwen, 2001, as cited in Chandler-Olcott, 2008, p. 251). 6 Slide: Waterbusters plays first 21 seconds 7 Slide(s): Still Images / Opening Scene includes three images: (1) the student on the bench, (2) the student going down the steps, and (3) the professor on the sidewalk. BUSTING OPEN WATERBUSTERS 13 APOLLO. The fact that these individuals represent someone, that they signify a role in a play (shudders) implies that they can also be considered stages in themselves. DIONYSUS. (Ignoring Apollo) Next, we hear orchestral music (mimes gentle conducting; CHORUS joins in) playing a pastoral theme. This gentle music contrasts with the two streams of water (mimes shooting; CHORUS joins in; APOLLO looks down his nose at the scene) pow, pow, pow, pow! directed, from an unseen source, at the student. The student raises his/her arms in defense but is overpowered and falls off of the bench. (DIONYSUS and CHORUS high five) APOLLO. The sprinklers, while not visible in the film, produce water which functions, as Honzl puts it, as a “stage prop” (Honzl, 1940/1998, p. 274), symbolizing aggression. DIONYSUS. (appealing to ZEUS) I thought we were not discussing connotations here. ZEUS. (speaking to APOLLO) Your brother has a point. APOLLO. My brother “discussed” connotations by his actions and extraneous verbalizations. ZEUS. (speaking to DIONYSUS) Your brother has a point. Proceed. APOLLO. (irritated) As I was saying... The sprinklers, while not visible in the film, produce water, which functions as a “stage prop” (Honzl, 1940/1998, p. 274). The action of this water—attacking passers-by—in turn signifies its characteristic nature. DIONYSUS. (whining) So is the water a prop or a character? (shrugs and turns back to the script) Within this first scene, then, we see the modalities of the— CHORUS. Spatial. APOLLO. —outdoors, moving from sitting on a bench to falling off a bench— CHORUS. Visual. DIONYSUS. —colors, costumes/clothing, furniture, streams of water— CHORUS. The auditory. APOLLO. —snore, music— CHORUS. Choreographical and gestural. DIONYSUS. —raising arms to defend self— CHORUS. Linguistic. BUSTING OPEN WATERBUSTERS 14 APOLLO. —subtitles— DIONYSUS. —all of which are stylistic choices made in the process of conveying the idea of a helpless student being assaulted and overpowered by water. No words have been spoken, and the few words of written text serve only to ground the setting. APOLLO. To answer the question, “Who or what is depicted here?” is partially to achieve the goal of describing the visuals at their most basic level. DIONYSUS. The scene fades, and a new scene takes its place, also set outdoors. This time— APOLLO. (cuts DIONYSUS off to forestall more theatrics; DIONYSUS is left with his mouth open) This time we see a person in sunglasses, a hoodie, shorts, and sneakers—hands in the front pocket of the hoodie—swaggering down a set of steps, toward the camera/viewer, in time to a synthesized beat reminiscent of rap music. DIONYSUS. A subtitle appears, which reads, “Later that same day…” Again— APOLLO. (as before) Again, two streams of water come from nowhere and assault the person. The person’s hand remain in the pockets; the person’s only defense is to duck and to turn his/her head—or, perhaps, cheek?—and to back away from the water. DIONYSUS. The scene changes a third time, we are again outdoors. Now we see— APOLLO. (as before) Now we see a man moving toward us—or the representation of a man, that is. One student has donned a ball cap and a mask of a middle-aged man. “He” struts to a clarinet playing rag-jazz; and a subtitle appears, which reads, “Soon after…” This man, too— DIONYSUS. (cuts APOLLO off and leaves APOLLO with his mouth open) —is assaulted by streams of water (mimes shooting; CHORUS joins in; APOLLO looks down his nose at the scene)—dzdzdzdzdzdzdz! He raises his hands, tries to defend himself, but is overpowered and falls flat on his back. (CHORUS and DIONYSUS high five) APOLLO. (appealing to ZEUS) Really? ZEUS. You must admit he is…entertaining. Proceed. APOLLO. (SLIDE: Still Images / Other Scenes8; CHORUS again assumes game-show model role) Continuation of the film reveals a makeshift newsroom set with two news reporters, wearing masks, sitting at tables who alternate reporting events related to the sprinkler mishaps. 8 Slide(s): Still Images / Other Scenes shows still images of the newscasters, protesters, and Waterbusters. BUSTING OPEN WATERBUSTERS 15 DIONYSUS. Outraged protesters, many wearing highly fluorescent colored wigs and bearing placards, bang (demonstrates) on the closed doors of the maintenance office, demanding that the sprinkler problems be solved (strikes a “Let justice be done” pose). APOLLO. (ignoring DIONYSUS) Intermittently, the Waterbusters appear, collectively at times and individually during others, wearing wigs similar to the protestors’ and offering solutions. DIONYSUS. (behaving himself) Stylistically, the videographers chose medium and full shots to frame the three subjects— APOLLO. —signifying relationships ranging from personal to social (Rodriguez, and Dimitrova, 2011, p. 55). DIONYSUS. Visually, they considered such things as length (distance) of the shot, prominence of the face, the ways color tones enhance realism, and poses or image acts by the subjects in the pictures (pp. 54-56). APOLLO. Aurally, the volume remains somewhat constant—there is no appreciable difference between one segment and then next— DIONYSUS. —which suggests the viewer/hearer should give equal weight to each incident. The sleeping student is no more and no less significant than the other two people. APOLLO. While we cannot initially see the backpacks of the Waterbusters, we notice the straps suggesting there are “power tools” concealed, which they intend to use. Furthermore, the combination of the camera position at an upward or dominant angle (see Hardin et al., 2002 in Rodriguez & Dimitrova, 2011) and the indication that the Waterbusters are all males (based on societally-construed norms), the underlying subtlety is that these individuals are powerful and can indeed handle the problem. ZEUS. As you have introduced connotative meaning into the conversation, speak now to that which you have described in terms of the mortal Eco’s (1994) idea of ostention. (SLIDE: Ostention9) CHORUS. (Reads Slide: Ostention; spelling bee voice) Ostention: a form of signifying, which occurs when a person (or, possibly, an object) having been “picked up [from] among the existing physical bodies, [is] de-realiz[ed]…in order to make it stand for an entire class” (Eco, 1994, p. 281). 9 Slide: Ostention includes this text: Ostention: a form of signifying, which occurs when a person (or, possibly, an object) having been “picked up [from] among the existing physical bodies, [is] de-realiz[ed]…in order to make it stand for an entire class” (Eco, 1994, p. 281). BUSTING OPEN WATERBUSTERS 16 DIONYSUS. Connotatively, the third level of Rodriguez and Dimitrova’s model, we interpret symbolically what each student is wearing and his/her actions. The first person wears a typical school uniform of shorts and shirt. Atop his/her head sits a green frizzy wig, one of the school colors and similar to those worn during pep rallies or spirit week skits. APOLLO. By ostention, this person symbolizes “rah-rah, go school” students, ones, perhaps who expend their energies in places other than class and end up sleeping on benches. DIONYSUS. The second person wears a zipped-up sweatshirt with the hood pulled up. “Hoodies,” are worn by people of many races, but they have become particularly identified with young African Americans. Combined with the rap music playing during this segment, the hoodie ostends this person into symbolizing African American students, perhaps even all non-White students. APOLLO. The third person wears a ball cap, suggesting someone not quite with the current trend of wig or hoodie. The ball cap combined with the middle-aged face mask and Dixieland jazz, ostend the one person into all older people on campus, those who usually are faculty and staff members. DIONYSUS. Through the visual, aural, and choregraphical modalities, then, we see a Typical (if stereotyped) White Student, a Typical (if stereotyped) Black Student, and a Typical (if caricatured) Professor/Adult, each of whom has been the victim of renegade waters. APOLLO. Clearly, the unverbalized— DIONYSUS. —but not unspoken—idea transcending the individual components is, APOLLO, DIONYSUS, and CHORUS. “This happened to us; it could happen to anyone; (pointing to audience) it could happen to you.” DIONYSUS. We perceive the images, as Rodriguez and Dimitrova put it, as “closely analogous to reality, they provide a one-to-one correspondence between what is captured by the camera and what is actually seen in the world” (Rodriguez & Dimitrova, 2011, p. 53). APOLLO. Even if we didn’t actually know the person being filmed by name, we can relate to the person as a person of the same social standing as we are; we empathize because we can easily see ourselves in the same predicament. ZEUS. And ideologically? (Slide: Ideologies10) 10 Slide: Ideologies contains three questions: (1) Who or what is threatened? (2) By whom? (3) Who or what holds the power to resolve the issue? BUSTING OPEN WATERBUSTERS 17 DIONYSUS. The water outbursts produced by these sprinklers represent wastage; they signify that there is an underlying problem of wastage. APOLLO. In particular contexts (rolls eyes at DIONYSUS and CHORUS), water outbursts could be conceived of as fun. In the context in which the water outbursts are portrayed, however, “Waterbusters” emerge. These Waterbusters represent those who depict water outbursts as a threat, thereby creating the social context in which conservation versus wastage becomes the ideological abstraction. DIONYSUS. Capable of the changeability described by Honzl (1940/1998), these Waterbusters first appear collectively as a theatrical sign, and then individually, before reappearing as a collection. Perhaps, in the process (looks pointedly at APOLLO) of creating the video, the students chose this particular order to indicate to spectators the importance of approaching this problem in a unified manner while at the same time emphasizing the necessity of each individual’s ability to make a difference. APOLLO. Whatever the case, one finds that semiotic phenomena strongly are designed to function similarly to “everyday conversational interaction” (Eco, 1977, p. 286). For instance, upon noting the individual presentations of each of these Waterbusters, spectators may decide to listen, to become waterbusters themselves, find a way to solve the problem, or to join the protest. DIONYSUS. (triumphant) Then you admit the video has cognitive, persuasive, and pragmatic meaning derived from the process the children used in deciding what to portray and how! APOLLO. I said spectators MAY decide to do these things. Given the crudity of the product itself, while I am forced to applaud their attempts, the students’ end product remains only an attempt at conveying such meaning. Vygotsky, Smagorinksy went on to note, also looked for “a sense of profundity (CHORUS puts index finger to temple and looks profound) and new planes of emotional experience,” and “paradoxical combination of form and material,” (CHORUS holds hands over heart and looks emotional) in addition to technical mastery (CHORUS makes fists and looks masterful). Surely you are not suggesting this video meets Vygotsky’s definition of art? (SLIDE: Art11) DIONYSUS. Surely art is in the eye of the beholder. (APOLLO looks DIONYSUS up and down, then nods knowingly at the audience) APOLLO. Surely it is so. DIONYSUS. Regardless, the video has other value. The mortal Figueiredo (2011) suggested that comics creators— APOLLO. Comics creators? Really, Dionysus— 11 Slide: Art contains the text What is Art? BUSTING OPEN WATERBUSTERS 18 DIONYSUS. Hear me out, Brother. (begins to pace up and down in lecture mode; CHORUS follows and mimics) Comics creators are information designers (p. 87) (SLIDE: Comics12) who work to “create meaning from fragments of data by organizing the selected pieces of data into an ordered view of the world” (p. 92). Further, Figueiredo drew on the 1985 work of Eisner who described comics as creating a “flow” across “segments of frozen scenes and enclosing them by a frame or panel” (as cited in Figueiredo, 2011, p. 92). APOLLO. And? DIONYSUS. If we consider “Waterbusters” as a moving comic strip—each scene fluid, rather than frozen, but still enclosed by transitions from scene to scene that fragments the data, and its creators as information designers—world builders—rather than as artists… APOLLO. Go on. DIONYSUS. …our task then becomes to glean and interpret the information presented not as art but as information about the world made over in the image of the creators, in this case, the students’ own selves (p. 88). APOLLO. (repeating slowly) “The world made over in the image of the crea--” You mean like gods? We’re supposed to think of these children as gods capable of creating worlds? (CHORUS whispers in APOLLO’s ear) APOLLO. Say! You’re right! (High fives CHORUS) Then you admit it is a product, a created world that is of ultimate importance? ZEUS. (stands and interjects with laughter) It appears you both have been had. In arguing for a product, Apollo, you have had to dissect and evaluate the artistic process. And you, Dionysus, in arguing for the process, have ended up with a product on which your evaluations rest. I declare this debate a draw. Shake hands (APOLLO and DIONYSUS obey) and let us close the veil over this scene. (ZEUS waves his hand over the earthly scene and turns to leave) APOLLO. (gathering his papers) Perhaps when these children have matured, they will produce something worthy of future discussion. DIONYSUS. (gathering his papers) It would appear what “these children” produced in their present immaturity was worth our present discussion. (APOLLO and DIONYSUS get in each other’s face during these next few lines; the CHORUS 12 Slide: Comics contains an image of a comic strip and this text with appropriate words in bold font: Comics creators work to “create meaning from fragments of data by organizing the selected pieces into an ordered view of the world” (Figueiredo, 2011, p. 92). BUSTING OPEN WATERBUSTERS 19 cringes and covers her ears) APOLLO. Future. DIONYSUS. Present. APOLLO. Future! DIONYSUS. Present! Zeus: (stepping between APOLLO and DIONYSUS) Silence! (ZEUS, APOLLO, DIONYSUS, and CHORUS freeze for a two-count beat, then bow to audience and take their seats) FINIS Afterthoughts on the process Dramatizing the data on paper, bringing the script to life, then tailoring the drama to fit the constraints of a presentation at an academic conference involved several iterations. Anne first created an incomplete draft sketch using the voices of the three researchers, with one person doubling briefly at the beginning as the Narrator. However, at the first video-conference readthrough, a fourth person was present who read the part of the narrator and who was agreeable to doing so at the conference. Hearing the four voices reading the parts, presented new options for the remainder of the sketch. We also discussed the uses of a playbill to give the audience introductory information and of slides to present information visually during the drama. Our concern was that conference attendees would not be expecting a theatrical performance and that they would not be familiar with the video on which the analysis and the performance was based. In the second draft of the drama, which is included in this paper, Anne changed the part of the Narrator to function as a Greek Chorus, a typical device found in most classical Greek tragedies, although used with varying effect (Weiner, 1981). With the Chorus acting as a bit of a foil, Anne heightened the contrast between Dionysus and Apollo by adding visual and verbal BUSTING OPEN WATERBUSTERS 20 comedic effects. Anne also included possible slides to be presented at particular points in the sketch, and she began drafting a playbill. At the same time, Jenifer worked to create a slide show presentation, which included background information about the initial video-composing project. In the second video-conference, we realized we were working from slightly different conceptions about what kinds of information the audience needed to make sense of the presentation. For instance, Jenifer felt the audience needed to see the entire three-minute video, while Anne felt the first 21 seconds was sufficient as the bulk of the analysis was focused on this segment. We also were scheduled to present last (of three papers), and we were concerned that we might not have a full 20 minutes to present. Saldaña (2003) observed that entertainment is the goal of theatre artists—not education or enlightenment, which is the goal of most researchers— and we were experiencing the tension between those two goals. We needed to be mindful that we had, as Saldaña (2003) put it, a “responsibility to create an entertainingly informative experience for an audience, one that is aesthetically sound, intellectually rich, and emotionally evocative” (p. 220). After discussion, we agreed the audience needed more information in order to enter into the aspect of being entertained. Too little knowledge might leave them merely confused or even angry at the thought their time was being wasted. Accordingly, we decided to expand the backstory by giving more information about the initial project, show the video in full, and rethink the dramatization. The third iteration is yet to be performed. Discussion of how the presentation is received will form the last part of this paper. BUSTING OPEN WATERBUSTERS 21 References Anderson, M. (2007). Making theatre from data: Lessons for performance ethnography from verbatim theatre. NJ: Drama Australia Journal, 31(1), 79-91. Apollo. (2004). Encyclopedia Mythica. Retrieved November 18, 2013, from Encyclopedia Mythica Online. <http://www.pantheon.org/articles/a/apollo.html> Athanases, S. Z. (2008). Theatre and theory partnered through ethnographic study. In J. Flood, S. B. Heath, & D. Lapp (Eds.), Handbook of research on teaching literacy through the visual and communicative arts, Volume II(119-128). Baines, L. (2008). Film, literature, and language. In James Flood, Shirley Brice Heath & Diane Lapp (Eds.), Handbook of Literacy Research: Visual, Communicative and Performative Arts, Vol. 1, pp. 545-557. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Bannerman, H. L. (2010). Movement and meaning: An enquiry into the signifying properties of Martha Graham’s Diversion of Angels (1948) and Merce Cunningham’s Points in Space (1986). Research in Dance Education, 11(1), 19-33. Bird, J. (2011). Performance-based data analysis: A dynamic dialogue between ethnography and performance-making processes. NJ: Drama Australia Journal, 34, 35-45. Burn, A. (2009). The case of rebellion: Researching multimodal texts. In J. Coiro, M. Knobel, C. Lankshear, & D. Leu (Eds.), Handbook of research on new literacies (pp. 151-178). New York, NY: Routledge. Carter, M. R. (2010). The teacher monologues: An a/r/tographical exploration. Creative Approaches to Research, 3(1), 42-66. Chandler-Olcott, K. (2008). Anime and manga fandom: Young people’s multiliteracies made visible. In J. Flood, S. B. Heath, & D. Lapp (Eds.), Handbook of research on teaching BUSTING OPEN WATERBUSTERS 22 literacy through the communicative and visual arts, Volume II. New York, NY: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Dionysus. (2007). Encyclopedia Mythica. Retrieved November 18, 2013, from Encyclopedia Mythica Online. <http://www.pantheon.org/articles/d/dionysus.html> Eco, U. (2003). Semiotics of theatrical performance (1977). In Brandt, George (Ed.) Modern theories of drama: A selection of writings on drama and theatre, 1840-1990. Oxford University Press: Oxford, England. pp. 279-287 Figueiredo, S. (2011). Building worlds for an interactive experience: Selecting, organizing, and showing worlds of information through comics. Journal of Visual Literacy, 30(1), 86100. Gouzouasis, P. (2005). Fluency in general music and arts technologies: is the future of music a garage band mentality? Action, Criticism & Theory for Music Education, 4(2), 2-18. Gray, J. (2009). Theatrical reflections of health: Physically impacting health-based research. Applied Theatre Researcher/IDEA Journal, 10, Special Section 1-10. Greenwood, J., & McCammon, L. A. (2007). The bridge, the trolls and a number of crossings: A foray into the ‘third space.’ NJ: Drama Australia Journal, 31(1), 55-68. Holle, K. A., & Colyar, J. (2009). Rethinking texts: Narrative and the construction of qualitative research. Educational Researcher, 38(9), 680-686. Honzl, J. (1998). Dynamics of the sign in the theater (1940). In Brandt, George (Ed.) Modern theories of drama: A selection of writings on drama and theatre, 1840-1990. Oxford University Press: Oxford, England. pp. 269-278. (Original work published 1940) Hung, K. (2001). Framing meaning perceptions with music: The case of teaser ads. Journal of Advertising, 30(3), 39-49. BUSTING OPEN WATERBUSTERS 23 Kazubowski-Houston, M. (2012). “A stroll in heavy boots”: Studying Polish Roma women’s experiences of aging. Canadian Theatre Review, 151, 16-23. DOI:10.3138/ctr.151.16 Kist, W. (2008). Film and video in the classroom: Back to the future. In James Flood, Shirley Brice Heath & Diane Lapp (Eds.), Handbook of Literacy Research: Visual, Communicative and Performative Arts, Vol. 2, pp. 521-528. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Learning Gate Community School Students. (2011). Waterbusters [Video]. University of South Florida, Tampa, FL. Retrieved November 18, 2013, from https://itunes.apple.com/institution/university-of-south-florida/id384490576#ls=1 Mendelson, A. L. (2008). The construction of photographic meaning. In James Flood, Shirley Brice Heath & Diane Lapp (Eds.), Handbook of Literacy Research: Visual, Communicative and Performative Arts, pp. 27-36. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Rodriguez, L., & Dimitrova, D. (2011). The levels of visual framing. Journal of Visual Literacy, 30(1), 48-65. Saldaña, J. (2003). Dramatizing data: A primer. Qualitative Inquiry, 9(2), 218-236. Schneider, J. J. (2011). The sustainability responsibility possibility project: Fall 2011. (Unpublished report). University of South Florida, Tampa, FL. Schneider, J. J. (2012). Analysis instructions. LAE7868: Symbolic Processes of Multimedia Literacies. University of South Florida, Tampa. Blackboard (no longer available online). BUSTING OPEN WATERBUSTERS 24 Schneider, J. J., King, J. R., Kozdras, D., Minick, V., & Welsh, J. L. (2012). Accelerating reflexivity? An ethnotheater interpretation of a preservice teacher literacy methods field experience. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 25(8), 1037-1066. DOI: 10.1080/09518398.2011.595740 Schneider, J.J., Kozdras, D., Wolkenhauer, N., Arias, L. (in press). Environmental E-books and Green Goals: Changing Places, Flipping Spaces, and Real-izing the Curriculum. Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy. Serafini, F. (2011). Expanding perspectives for comprehending visual images in multimodal texts. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy 54(5), 342-350. doi:10.1598/JAAL.54.5.4 Smagorinsky, P. (2011). Vygotsky’s stage theory: The psychology of art and the actor under the direction of Perezhivanie. Mind, Culture and Activity, 18(4), 319-341. Weiner, A. (1980). The function of the tragic Greek chorus. Theatre Journal, 32(2), 205-212. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3207113 White, V., & Belliveau, G. (2011). Multiple perspectives, loyalties, and identities: Exploring intrapersonal spaces through research-based theatre. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 24(2), 227-238. DOI: 10.1080/09518398.2010.495736 Zeus. (2005). Encyclopedia Mythica. Retrieved November 18, 2013, from Encyclopedia Mythica Online. <http://www.pantheon.org/articles/z/zeus.html> BUSTING OPEN WATERBUSTERS 25 BUSTING OPEN WATERBUSTERS 26 Table 1. Patriann Smith’s approach to analyzing various layers of the student-produced video “Waterbusters.” Segment’s Analyzed and How Theorists & Methods Considered Opening segment*: Humans and sprinklers as representative of larger Eco (1994) and ostention populations; sprinklers as prop and as Honzl (1940/1998) and collective art character; bench, steps, sidewalk, and humans as stages Waterbusters segments: Waterbusters as implicit persuaders Stylistic choices and ideological implications of visual text in: Opening segment Newsroom segments Protestors segment, and Waterbusters segment Rodriguez & Dimitrova’s (2011) fourtiered model Hall (1966), Hardin, et al. (2002), Lister & Wells (2001), Pieterse (1992), and van Leeuwen (2001) and camera framings (as cited in Rodriguez & Dimitrova, 2011) Mendelson (2008) and candid vs. posed images Serafini (2011) and ideological representation in images Kist (2011) merging literary and academic Baines (2011) merits of books vs. films Gouzouasis (2005) and fluency, FITness (appropriate selection) vs. FATness (creation) Auditory text in: Opening segment (snore and music choices) Protestors scene (noise) Inherent essence in product vs. structural Smagorinsky (2011) and Vygotsky’s perspective in process choices using view of art and children costuming choices as an example *Possible segments to consider (in order of appearance) were (1) opening segment, (2) newsroom segments, (3) protestors and maintenance office segment, (4) Waterbusters segments, and (5) closing credits. BUSTING OPEN WATERBUSTERS 27 Table 2. Anne Anderson’s approach to analyzing various layers of the studentproduced video “Waterbusters.” Segment’s Analyzed and How Theorists & Methods Considered Alphabetic and visual texts in opening segment: Chandler-Olcott (2008) and which modes to emphasize Student on bench Student walking down steps Kress and Van Leeuwen (2001, as cited in Chandler-Olcott, 2008) and Non-student strutting down sidewalk combining the modes to create a whole All attacked by water; what do they event represent (ostention) Eco (1994) and ostention Other possible interpretations Burn (2009) and interpretation of text Impact of the collective whole Honzl (1976) and collective art Other research questions raised Stylistic choices and ideological implications of visual text in all four levels of: Opening segment Auditory text at all four levels in: Opening segment Rodriguez & Dimitrova’s (2011) fourtiered model Rodriguez & Dimitrova’s (2011) fourtiered model Hung (2001) and how music affects what we see Rodriguez & Dimitrova’s (2011) fourtiered model Bannerman (2010) and movement Schneider (2011) grant application Smagorinsky (2011) and Vygotsky’s view of art and children Figueiredo (2001) and Eisner’s view of comics Choreographic choices (gestural texts) at all four levels in: Opening segment Purpose of the video: As part of grant application As video in and of itself o Art? o Imagined world? Possible affective influences on students making video *Possible segments to consider (in order of appearance) were (1) opening segment, (2) newsroom segments, (3) protestors and maintenance office segment, (4) Waterbusters segments, and (5) closing credits.