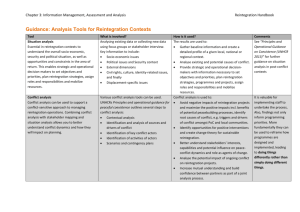

Reintegration Post-Deployment

advertisement