Subcultures - The W&M Digital Archive

advertisement

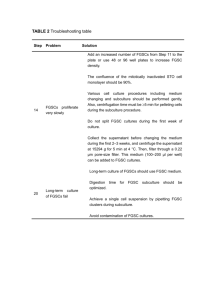

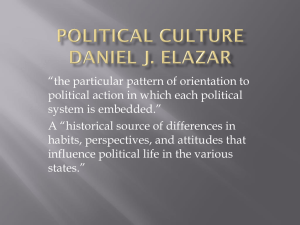

Political Culture in the Lower Shenandoah Valley: Evaluating Elazar Matthew Reges Summer 2008 The Valley of the Shenandoah River runs southwest to northeast along the western border of Virginia and the eastern panhandle of West Virginia, encompassing forests, farms, and such small cities as Staunton, Lexington, Harrisonburg, Strasburg, Winchester, and Harper’s Ferry. Walled by the Blue Ridge on the east and the Alleghenies on the west, the history and politics of this region have a tone distinct from both the Appalachian highlands and the coastal flatlands. Fear of Indian attack and the difficulty of east-west travel over the mountains slowed the settlement of the Shenandoah Valley by Virginia’s English population. It was first peopled in the 1730s by waves of German and Scotch-Irish who traveled up the valley from Pennsylvania. Since then there has been a mixing of cultures and the emergence of a distinctive synthesis affecting history, economics, and politics. The lower Shenandoah Valley is the only home I have known, and in this essay I will apply a leading theory in political science to the case I know best. I hope to benefit the literature of political culture and also that of Valley politics. Daniel Elazar, late professor of political science at Temple University, helped broaden the scope of political science inquiry beyond formal institutions with his four decade study of political culture. Political culture is “the particular pattern of orientation to political action in which each political system is embedded.”1 It is “the widely shared values, social norms, and institutions that structure and legitimate relationships within a political community.”2 A political culture is broader than party platform or ideology and may encompass several of each; it is the set attitude and philosophy of citizens with regard to governance. The values of political culture exist almost subconsciously and can be difficult to observe without variation for contrast. Elazar and his followers have sketched the broad American political culture, emphasizing representation, justice and fairness, equality of opportunity, individualism, and incremental change. There has been more work, however, on the variation of political culture in different parts of the United States. “Political culture is particularly important as the historical source of differences in habits, perspectives, and attitudes that influence political life in the various states.”3 Elazar suggests that political subculture is part of why Minnesota and Wisconsin so often advocate for new federal programs, why West Virginia and Pennsylvania have had difficulty with civil service reform, and why Texas and South Carolina put such importance on militia and National Guard units. The political subcultures of the United States have their origin in the colonial and early national periods. They emerged from the values and mannerisms of diverse settling groups in the face of economic, geographic, and social pressures. New immigrants to an area slowly adopted the political culture of their new home. Perhaps more importantly, settlers moving inexorably west carried their political thoughts and practices with them. Elazar identified three political subcultures in the United States. These three originated in the thirteen colonies and were carried like river sediment west to the Pacific. 1 Elazar, Daniel J. “American Federalism: A View from the States.” p. 109 Miller, David, David Barker, and Christopher Carman. “Mapping the genome of American political subcultures: a proposed methodology and pilot study.” p. 303 3 Elazar, Daniel J. “American Federalism: A View from the States.” p. 110 2 “The moralistic political culture emphasizes the commonwealth conception as the basis for democratic government.”4 The Puritans of New England saw government as a great cooperative endeavor where competition could result in progress for the community. Good government is honest, selfless, and devoted to the public welfare. The scope of the public versus the private is relatively large, because community involvement is generally good. Political participation is very important and the domain of every citizen. Party machinery and loyalty are secondary to issues, beliefs, and broader goals. The shining city on the hill remains an appropriate symbol for the strengths and flaws of the moralistic culture. And “wherever Puritan blood has gone, Puritan traditions have been carried –that is essential.”5 From its New England roots, the stream of moralistic settlement flowed across upstate New York, the Great Lakes coast and the Upper Midwest. Sixth-generation Yankees and like-minded Scandinavians settled the Pacific Northwest and parts of Kansas. Yankees turned Mormon and created an enclave in Utah. The moralistic political culture spans the left-right spectrum and encompasses many policies with the common thread of greater community involvement for the greater community good. New Hampshire’s large citizen legislature, Massachusetts’s pioneering healthcare system, and the school board struggles over intelligent design in Kansas are all modern manifestations of political moralism. The individualistic political culture may be symbolized by a bazaar or the floor of a stock exchange. Government serves utilitarian concerns, advancing the interests of those citizens participating.6 Politics is a business, with rules, incentives, and partnerships. It is expected that government action will be limited to managing the marketplace and providing tangible goods. Politics is less sanctified and often perceived as dirty, and cohesive political parties function like efficient corporations, working for their stakeholders’ good. New programs are launched only in response to the demands of political consumers. Politics is more professional, with less amateur participation and less space for ideology. The ethnically and religiously diverse groups settling the middle colonies settled on pluralism and individual opportunity as political rules. From New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Maryland, the individualistic culture spread through much of the Midwest. Big machines in New York, St. Louis, and Chicago, and sparse areas around the Rocky Mountains all adopted this give-and-take, professional philosophy. The confining of government to economic concerns and the strength of party organizations and professional bureaucracies shows that the individualistic political culture is alive and well. After many decades and changes, the plantation remains the best analogy for the traditionalistic subculture. Government is dominated by an elite political class which uses policy and bureaucracy to preserve itself and its interests. The common citizen is not regarded as a Puritan’s brother or a boss’s client, and expensive new initiatives are undertaken reluctantly unless out of noblesse oblige or pragmatic concern for the power base. Politics is often a part-time vocation, and formal party structures take a back seat to personal associations and relationships between leaders. Because governing is the realm of a privileged few, political participation is most limited in the traditionalistic culture. 4 ibid. p. 117 Mathews, Lois K. “Two Centuries and a Half of New England Pioneering.” p. 109. 6 Elazar, Daniel J. “The American Mosaic” p. 230. 5 The Old South nurtured the traditionalistic subculture, and as Southern farmers pushed west to find new opportunities, they took their political ideas and structures to Missouri, Texas, and the desert Southwest. Southern planters and soldiers also rooted in Hawaii, and some desperate farmers made the post-war trek to Alaska. Beyond these outliers, though, the traditionalistic subculture remains rooted in the Confederacy. Demographic change –migration from around the country and the world –is rapid, and it remains to be seen whether the newcomers will adopt the traditionalistic values, as Elazar would theorize, or whether the political culture will be diluted to insignificance in our digital age. Political subcultures do not have clean boundaries at state lines; as people and ideas move, cultures mix. Daniel Elazar notes an individualistic-moralistic blend emerged in Rhode Island, where the communitarian impulse was moderated by an early population of outcasts and rogues. Two blended subcultures are worth noting here: the traditionalistic-moralistic “Appalachian” subculture and the traditionalistic-individualistic “Southern frontier.” The labels are my own. Elazar’s map of political subcultures features a vein of traditionalist-moralist labeled TM running along the Appalachians from Hampshire and Mineral counties in West Virginia, to which one could add Garrett County in far western Maryland, through Lee and Wise counties in far southwest Virginia, the western Carolina highlands, eastern Tennessee including Chattanooga, and northern Georgia and Alabama including the cities of Decatur and Huntsville. The distinctive political milieu of this region has lately been highlighted by the Democratic presidential primaries and the books of Virginia Senator Jim Webb. The old dynamic of tuckahoe and cohee remains useful, and the Appalachian political subculture can be partly understood by its opposition to the pure traditionalistic practices of the lowland state capitals in Richmond, Raleigh, Nashville, Columbia, Savannah, and Montgomery. Historically, the Appalachian areas were strongholds of opposition to elite machines in these seven states, and in Virginia the differences of political opinion and practice were so strong as to lead to the secession of 1864 and the dominion in West Virginia of a more modest and populist system. The religion of Appalachia tends to the evangelical; Pentecostal assemblies are common, as are Calvinist Lutherans and Presbyterians. This is another way that Appalachia opposes lowlands, with their more staid Methodists, Baptists, and Episcopalians.7 The gay marriage amendment of 2006 shows the moralistic tinge of Appalachia in contrast to pure traditionalism. The counties with the highest percentage votes in favor of a gay marriage ban were in the mountainous southwest, with nearly 90 percent voting for. In traditionalistic but equally conservative Northern Neck and Southside 7 Zelinsky, Ira. “The Religious Geography of the United States.” p. 160. See also Tillson’s “Gentry and Common Folk” p. 65 for a note on fiercely individualistic highland Presbyterians in history. I can attest for the relative prevalence of Pentecostals in Hampshire County, West Virginia and that of Methodists in adjacent Frederick County, Virginia. The highland Lutheran and Presbyterian congregations also tend to be more activist and evangelical than their Valley counterparts. I have no citation for this observation, only my life of experience. Elazar’s method for the Chicago studies was similar, and it was criticized on the grounds of academic rigor. Ira Sharkansky has made quantitative studies that confirm Elazar’s “intuitive assessments.” See “The Utility of Elazar’s Political Culture” p. 247 and also Joslyn’s “Manifestations of Elazar’s Political Subcultures” in Publius 10:3. communities, the amendment received closer to 70 or 75 percent.8 The success of populist Democrat Jim Webb in the Southwest over patrician Republican George Allen despite the success in this area of the conservative marriage measure illustrates well the impact of political subculture on voting behavior. Elazar’s subculture map places a TM in the area of Staunton and Harrisonburg which connotes the entire Shenandoah Valley.9 Before introducing my hypothesis and data, I will explain the traditionalisticindividualist subculture, labeled TI by Elazar and which I call “Southern frontier.” This mix appears in Virginia around the Dismal Swamp and in western West Virginia closer to the Ohio River.10 It also exists in the southernmost part of Illinois, central Missouri, the foothill areas around Birmingham and Atlanta, and finally the forested areas of Louisiana and east Texas. Migrants from the latter area moved inland to Oklahoma and carried their politics with them. To generalize its scope, the Southern frontier subculture exists at the geographic edges of the South, nearly girdling the land border of the Confederacy. This fringe status explains some of the of the subculture’s traits. Climate and geography made the plantation system was less viable, and commercial agriculture and the slave economy never flourished on the periphery as they did in, for instance, the pure traditionalistic state of Mississippi. The voting population “possessed only limited social cohesion:”11 the Cajuns in Louisiana, Mexicans in Texas, and Germans in northwestern Virginia constituted significant minorities that made political demands and did not share Cavalier values.12 Where living was harder and populations more diverse, elements of the individualistic subculture, with its emphasis on providing services, strong party machines, and staying out of personal life, infused the traditionalist model. However, “Valley gentry obtained the support of provincial leaders and thus successfully replicated the political institutions established [on the coastal flatlands].”13 Leaders on the Southern frontier looked to their purist capitals for inspiration and often for religion, but their local decisions were moderated by the distinct, more hard-scrabble local needs. The above research suggests that the political culture of Virginia’s lower Shenandoah Valley is not purely traditionalistic: the German and Scotch-Irish element is too strong, and the plantation never thrived. However, the Appalachian TM label seems inappropriate, as well, due to a lack of committed public participation and a small-government tendency in both parties. Moreover, Valley elites have for more than two centuries consciously emulated some of the political, legal, and even architectural structures of their Tidewater peers. I hypothesized that Elazar’s use of the TM label for the Valley was inaccurate and imprecise, failing to acknowledge the northern settlement stream of the 18th century and the political and economic realities that exist there, distinct from both Appalachia to the west and the 8 Virginia State Board of Elections. “2006 Official Results. Constitutional Amendment One: Marriage.” Obtained online. 9 Elazar, Daniel J. “American Federalism: A View from the States.” p. 125. 10 Beeman, Richard R. “Robert Munford and the Political Culture of Frontier Virginia.” p. 169. Beeman’s literary analysis of politics in early Southside Virginia bears a striking resemblance to practices and beliefs of the equally unsettled Shenandoah Valley. Glaser makes an interesting case study of mid-1990s Southside in “The Hand of the Past in Contemporary Southern Politics” p. 88. A parallel case study is in east Texas. 11 Tillson, Albert H. Gentry and Common Folk.” p. 66. 12 Some of the distinctions between New England and the South can be traced back to the English Civil War. See Ellis, Richard J. “American Political Cultures.” p. 101 13 Tillson, Albert H. “Gentry and Common Folk.” p. 64. flatlands to the east. The subculture of the Southern frontier would more appropriately capture the values, norms, and institutions of politics in my home. To illuminate this subculture, I interviewed seven local elected officials over a two-week period in May. All were eager to speak with me and answered my questions thoughtfully and graciously. Their stories and opinions shed light on their shared political culture and the variations within it. Jill Holtzman Vogel is, at 39, the youngest member of the Virginia Senate’s Republican caucus, one of its two freshmen, and its only woman. She is a fast-moving and dynamic legislator but remains rooted in the mores of her home. She confesses “a strong sense of place” and being “wedded to where I’m from.”14 The Holtzman name is an old one in Shenandoah County, and her father is a prominent oil and gas distributor. After attending the College of William & Mary and law school in Chicago, she worked in election law for the Republican National Committee, eventually starting her own practice in that field. While she is not an automatic party-line vote, notably breaking with her caucus in her first session on a handful of energy-related votes, her commitment to the national organization, her private consultations with Republican colleagues and candidates at every level of government, and her integration into the party structure is typical of Elazar’s individualist model. Also typical and with no prodding on my part, she acknowledged politics as a business relationship: “You [the supportive constituent] have got to feel like you got your money’s worth. If you took the time to go to the polls, you oughta know what I did.” Ms. Vogel also displays characteristics of the traditionalistic subculture’s hierarchical elitism.15 Unlike the individualistic legislators of New Jersey and Illinois, she does not consider politics a profession and is frustrated when partisan deadlock and special sessions impair her career and family life. She is not in politics for monetary gain; having personal and family wealth “it never crossed my mind what the compensation would be.” And she does not dream of holding her seat for decades; like Daniel Morgan long before her, a brief legislative stint suffices. She was elected by a small margin on a 38 percent turnout and quite satisfied with this level of participation; there is no moralistic desire to democratize. “Big pledges, that’s what makes it work,” she said as she acknowledged the role of a fundraising elite. Senator Jill Holtzman Vogel is a young legislator, but she carries the traditions of the Southern frontier. Like Ms Vogel, Delegate Clifford “Clay” Athey has a family history in the Valley, going back to the 1760s. His family has a four-generation history with his Methodist church. Athey works with his wife and sister as a civil attorney in Warren County’s seat of Front Royal, and like Vogel he does not see politics as a full-time endeavor. The roles of father and husband come first, followed by faith, business, and the then public life. “I’ve never been a person who is desirous of being elected at all costs,” and this less professional orientation to government is typical of Elazar’s traditionalists.16 Of the low salary for a state delegate, Athey says, “I like the idea that person who gets to the General Assembly goes to contribute, not to get a salary.” Taking care of a dependent community is important. 14 Jill Holtzman Vogel. Personal interview conducted Tuesday, May 20, 2008. Richard Ellis gives American hierarchy and deference a chapter’s treatment in his “American Political Cultures.” 16 Clifford Athey. Personal interview conducted Friday, May 23, 2008. 15 Athey sees two roles as state legislator: a service provider for his district and an arbiter who can “permit change t occur in an orderly fashion.” This kind of noblesse oblige typifies the traditionalistic, as does his dismissive view of political parties, which should be “nothing but vehicles for ideas.”He has consistently broken with the state Republican Party to help protect his rural environment. Athey believes that he wins reelection because he does good work for his voters and shares their conservative values. A fourterm delegate, Athey has never faced intense opposition, and voter turnout in his district has been low. He sees this lack of participation as a vote of confidence, that he is “protecting the minority.” In Clay Athey, Elazar’s traditionalist and individualist are visible, the former more clearly. Dennis Morris met me at a truck stop in Shenandoah County, not far from his family farm.17 He graduated from the local high school and community college, and then at age 22 ran for the county board of supervisors. He won a close race and has held the seat for more than thirty years, rarely facing opposition and occasionally serving as chairman. An important part of his role on the board is to house institutional memory and provide stability. A pure individualist would not stay so long in such an economically unrewarding seat, and a pure moralist would yield presently to give another citizen a chance to participate; in the traditionalistic subculture, however, Morris’s tenure is the honorable contribution of good family. Political activity does not consume his time, and he gives priority to his family and his farm work. These traditionalistic elements, however, are joined by some others. Morris is unusual among county supervisors in that he holds monthly informational meetings for the voters of his district. They occur at a central location and discuss the news, issues, and initiatives of the county. The June 2008 meeting detailed a community farm that provides for the locality’s unemployed, impoverished, and disabled population. This kind of public involvement could serve as a flag for the Appalachian or the Southern frontier, but I am inclined to label it the latter because it is billed to district voters rather than all residents generally, suggesting a kind of local machine and the voters’ getting their money’s worth. Morris also leans individualistic in his partisan involvement, actively advising, assisting, and endorsing younger Republicans. Stuart Wolk grew up in the DC suburbs of Prince George’s County, Maryland, where some of his family still lives. After graduating from Virginia Commonwealth University in 1975, he moved to Frederick County and has remained ever since. In 1995, Wolk ran in first round of county school board elections after that body changed from appointed to elected membership. He had “the traditional, kind of trite thought of giving back to a community that’s been good to me.”18 He sought advice from the courthouse crowd of local political elites, notably the county clerk, as well as his Methodist minister.19 The race was genial, and Wolk has been reelected three times without opposition, taking turns on every committee and serving one term as chairman. He is disappointed by the low turnout in his off-year elections: “We’re doing all the right things, but people are by nature apathetic.” 17 There was a glitch with the digital recording of the interview with Mr. Morris, conducted on Wednesday, May 28, 2008, and no direct quotations are available. 18 Stuart Wolk. Personal interview conducted Tuesday, May 27, 2008. 19 The influence of the courthouse crowd in rural Virginia dates almost to the founding of the colony and continues in many places today, sometimes with the same family names. See Sydnor’s “County Oligarchies” p. 92. Wolk’s opinions and the nature of board, which cannot levy its own taxes, have often thrown him into conflict with the fiscally conservative county board of supervisors. His relatively liberal views, however, should not be conflated with the moralistic subculture of the Northeast; Huey Long and Harry Byrd sprouted from the same soil.20 When Wolk spars with recalcitrant supervisors, he “agrees to disagree without being disagreeable.” “We don’t air our dirty laundry publicly,” adding that trenchant politics would only help the newspaper publisher. At their best, Elazar’s traditionalistic elites interact this way, reaching positive outcomes while preserving their own public images. In the same vein, Wolk is not worried about his $4,500 annual salary. The school board position does not throw the differences of political culture into stark relief, and Wolk does not epitomize any subculture, but the Old Line State native’s response to conflict and his approach to participation leans slightly to the traditionalistic. The subculture model seems to fit Mike Butler awkwardly at best. Butler grew up in Newport News, becoming politically active in the campaign of Hubert Humphrey and the anti-Byrd Organization candidacies of Henry Howell and J. Sargeant Reynolds. A Virginia Tech-educated expert on public health and safety issues, Butler has lived in Winchester for the latter half of his life. He was an active volunteer in community service groups, neighborhood organizations, and his Presbyterian church before being appointed by a Republican majority to fill a City Council vacancy in 2000.21 He has since been reelected twice. He has little to do with party politics: “I very much vote the man.”22 Butler remains involved in community service and regularly attends neighborhood association meetings around the city of Winchester. He likes listening to citizens directly, seeing them at the grocery store or coffee shop, “government right to the people.” He believes that “government is a team sport” and backs citizen advisory panels on important issues as well as more democratic ward districting. Elazar’s traditionalists tend to mistrust bureaucracies as loose cannons or professional threats; Butler, however, “put[s] a lot of faith in career staff” and counts them as vital members of the team.23 The closest label for Butler’s ideas on Elazar’s typology would be the pure moralistic. The Puritaninspired New England values of direct democracy, civic progress, and moral imperatives with little tolerance for political shenanigans or partisan squabbling mesh with Butler’s responses. It is difficult, though, to see a long geographical-historical origin for his beliefs, and Elazar’s theory seems to fall short. The formative experiences of the 1970s are clearer causes, and it may be that such turbulent times can overwhelm the more subtle influences of political culture. Despite a difference in core beliefs about government, Butler’s geniality and civic commitment have allowed him to flourish in a traditional city. Delegate Beverly Sherwood has also adjusted to the Valley after moving, but she has done so more seamlessly. Now the senior female in Virginia’s lower house, she has represented Winchester and Frederick County since 1993. Before that election she served as a neighborhood activist, appointed planning commissioner, and elected county supervisor. Sherwood is a native of Ossining, New York, a 20 Chandler, David L. “The Natural Supremacy of Southern Politicians: A Revisionist History.” p. 236 and 348. In true Winchester fashion, the first round of courting and vetting for his appointment occurred at a Handley Judges high school football game. 22 Mike Butler. Personal interview conducted Friday, May 23, 2008. 23 Elazar, Daniel J. “The American Mosaic” p. 238. 21 rural area in the southeast part of the state –individualistic, business-machine country for Elazar –and she has farmed in Frederick County for about thirty years. Of my seven participants, Sherwood was most friendly to party politics, supporting log rolling and reciprocal bloc votes. “Voting as a [House Republican] caucus, we are really powerful.”24 She said “behind-the-scenes” four times over 23 minutes and is particularly proud of her work on complex environmental, infrastructure, and public safety bills. Unlike her peers Clay Athey and Jill Vogel, Sherwood sees her legislative job as a full-time commitment despite the low pay. “My husband supports what I do;” “when I’m home, I do a lot of getting out” to meet constituents. “I can do a lot of campaigning at the grocery store. It takes me a long time to shop.” I see in Sherwood many traces her New York political upbringing, but it is possible that her relatively long experience in the partisan scene of Richmond is the cause and not the effect of her political philosophy. Causation can be frustratingly difficult to show with a small sample and qualitative data. Sherwood’s partisanship and professionalism seem distinctly individualistic, but her adult life on the Southern frontier has made a mark. On redistricting, she said plainly and with a hint of elitism, “I feel very protective of Frederick County as mine.” She has had a Democratic opponent only once since 1995, and her safe seat “allows me to legislate more.” Community involvement and influence are important, but when I asked what she liked about her legislative work, she was quick to answer: “I love the arena.” Like Wolk, Butler, and Sherwood, Karen Schultz moved to the Winchester area to work and raise a family. More than any of the other immigrants, however, she came prepared, moving from Anderson County in east Texas, a place “much like Winchester, proud and conservative.”25 More western than southern in character, and its dense forests and bayous hampered the development of plantation economics and hierarchical control in a way that parallels the Shenandoah Valley.26 Schultz’s family has a history of leadership in the area, and her father was a state legislator. “Growing up, public service was always a given.” In her adult home, Schultz is active in her Presbyterian church and local boards for health and human services. She teaches Shenandoah University and has served on the appointed city school board. In November 2007, she lost an expensive and bitter senate race to Jill Holtzman Vogel. Schultz’s approach to party politics mixes the traditionalist and individualist. Political participation is low because “there’s a lack of time” and informed commitment among common citizens, which necessitates a degree of elitism. She was encouraged to run by state and local leaders from both parties, and individual associations were more important than official connections. For her, the crucial relationships in politics are personal, not professional. However, she would like to the state Democratic Party to “mentor and encourage individuals at all levels,” penetrating to the grassroots to recruit candidates, mobilize voters, and contest more races.27 Such an aggregate of friendships and contacts to win elections is reminiscent of the Byrd machine in the Valley half a century before. 24 Beverly Sherwood. Personal interview conducted Tuesday, May 20, 2008. Karen Schultz. Personal interview conducted Tuesday, May 27, 2008. 26 Karen Schultz. Personal correspondence by electronic mail. August 27, 2008. 27 Elazar notes that recruitment is a key function of parties in the traditionalistic subculture. See “The American Mosaic” p. 239. 25 Seven interviews with local politicians show a remarkable degree of consistency around questions of political culture. This consistency suggests the existence of distinct political subculture on the Southern frontier that combines elements of the traditionalistic and individualistic subcultures from Daniel Elazar’s typology. The combination may be the result of historical, geographic, and economic factors that continue to influence the way long-time residents perceive the role of government. The lower Shenandoah Valley is less keen on direct democracy and broad public participation than other parts of the United States. Political parties are of moderate importance, less than purely individualistic areas like eastern Pennsylvania but more than purely traditionalistic ones like the coastal Carolinas. Personal associations –hierarchical elitism –picks up the organizational slack of formal parties, and these associations sometimes foster bipartisanship. Elite political service is not a professional activity, and elected officials are satisfied with their relatively low pay and infrequent meetings. There tends to be a skepticism of professional bureaucrats, who are carefully vetted and closely watched. The sample of interviews is diverse enough to dismiss some confounding variables. That Jill Vogel (the Senate’s most junior female member) and Beverly Sherwood (the House’s most senior female member) share ideas on the role of a party suggests that political subculture crosses generations. The interviews cross the political spectrum, suggesting that a political subculture and encompass or transcend ideology. Three of the interviews were of natives to Warren and Shenandoah counties, and four were of immigrants from other parts of the United States. Comparing these groups, it is interesting to see some convergence. While Karen Schultz moved from one part of the Southern frontier to another, the original subcultures of Stuart Wolk and Beverly Sherwood do not match that of the Valley, and during their adult lives they acquired some noticeable traits. It may be that political subculture can not only be transmitted from one native generation to the next but also from a native majority to newcomers. It may be concluded, in agreement with much of the literature, that Daniel Elazar’s theory of political subcultures is a useful way to consider the political orientation of a region. Elected officials in the lower Shenandoah Valley show the mixing of Elazar’s traditionalistic and individual subcultures to form a Southern frontier distinct from the either pure form as well as from the Appalachian region to the west. In Elazar’s map of political subcultures that appears in American Federalism, the TM label in the area of Harrisonburg that signifies the Valley should be a TI. The theoretical framework is correct, but Elazar may have overestimated the extent of the Appalachian influence, underestimated the orientation of the residents towards Richmond, or neglected the definitive immigrant stream that was German and ScotchIrish, Lutheran and Presbyterian. For three centuries, the Shenandoah Valley has existed as a distinct part of Virginia’s politics. It has contributed notable leaders, including the architect of the machine that dominated the 20th century in the state. Beverly Sherwood noted that her regional delegation remains formidable when it votes as a bloc. I hope that this essay will contribute to the literature on Valley politics and to the understanding of political continuity and change in my home. Bibliography Beeman, Richard R. “Robert Munford and the Political Culture of Frontier Virginia.” Journal of American Studies. 12.2: 169(14). Chandler, David L. “The Natural Supremacy of Southern Politicians: A Revisionist History.” Doubleday & Co., Inc. New York: 1977. Elazar, Daniel J. “American Federalism: A View from the States.” 3rd Edition. Harper & Row. New York: 1984. Elazar, Daniel J. “The American Mosaic.” Westview Press. Boulder, CO: 1994. Ellis, Richard. “American Political Cultures.” Oxford University Press. New York: 1993. Glaser, James M. “The Hand of the Past in Contemporary Southern Politics.” Yale University Press. New Haven, CT: 2005. Joslyn, Richard A. “Manifestations of Elazar’s Political Subcultures: State Public Opinion and the Content of Political Campaign Advertising.” Publius. 10.3 (Spring 1980): 37(21). Miller, David, David Barker, and Christopher Carman. “Mapping the genome of American political subcultures: a proposed methodology and pilot study.” Publius. 36.2 (Spring 2006): 303(13). Sharkansky, Ira. “The Utility of Elazar’s Political Cultures: Research Note.” Polity. 2.1 (Fall 1969): 66(18). Reprinted in “The Ecology of American Political Culture: Readings.” Daniel J. Elazar and Joseph Zikmund Jr., eds. Thomas Y. Crowell Company. New York. 1975. Sydnor ,Charles. “County Oligarchies.” In “The Ecology of American Political Culture: Readings.” Daniel J. Elazar and Joseph Zikmund Jr., eds. Thomas Y. Crowell Company. New York. 1975. Tillson, Jr., Albert H. “Gentry and Common Folk: Political Culture on a Virginia Frontier 1740-1789.” The University Press of Kentucky: 1991. Virginia State Board of Elections. “2006 Official Results. Constitutional Amendment One: Marriage.” http://www2.sbe.virginia.gov/web_docs/Election/results/2006/Nov/htm/l_141.htm. Updated November 7, 2006. Accessed August 20, 2008. Zelinsky ,Wilbur. “The Religious Geography of the United States.” In “The Ecology of American Political Culture: Readings.” Daniel J. Elazar and Joseph Zikmund Jr., eds. Thomas Y. Crowell Company. New York. 1975.