How sex offense registries fail youth and

advertisement

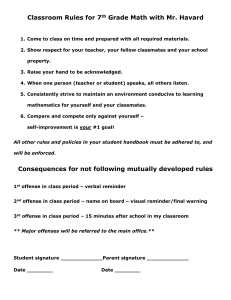

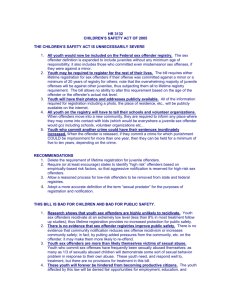

Registering Harm How sex offense registries fail youth and communities History and Origins of Sex Offense Registries During the 1990s, a spike in media coverage of sex offenses led to an outbreak of laws aimed at people convicted of sex offenses at the state and national levels. However, at the same time, the rate of reported violent offenses and forcible rapes during these years fell dramatically. The Federal Bureau of Investigation’s Uniform Crime Reports show that violent offense rates fell 25 percent during this time and the rate of forcible rapes dropped 19 percent. Sex offense legislation and policy 1994 – The Jacob Wetterling Crimes Against Children and Sexually Violent Offender Act (Wetterling Act) required states to compile a list of individuals convicted of violent sex offenses against children to register with the police for a period of 10 years. 1996 - Megan’s Law amended the Wetterling Act by mandating community notification for 15 years after the release of adults convicted of violent sex offenses who were released into the community. 2003 – The Dru Sjodin National Sex Offender Public Registry (NSOPR) joins state webbased registries to a single federal registry available online. The law also makes it a felony for persons on a registry to fail to update their contact information and whereabouts. 2006 – The Adam Walsh Act (AWA) mandates that states comply with federal guidelines or lose federal funding. In most instances, states that comply with Adam Walsh will have to both expand their registries to include children and increase the number of offenses for which registration is required. The Adam Walsh Act (AWA) explained Title I of the AWA mandates a national sex offender registry and provides a comprehensive set of minimum standards for sex offender registration and notification in the United States: • Requires that youth register, if prosecuted and convicted as an adult OR (a) if offender is 14 or older at time of offense AND (b) adjudicated delinquent for an offense comparable or more serious than “aggravated sexual abuse” OR adjudicated delinquent for a sex act with any victim under the age of 12. • Incorporates more sex offenses for which registration is required. • Requires people to provide more extensive registration information, including photos. • Makes the registry retroactive. People convicted of sex offenses prior to AWA’s passage are subject to SORNA’s registration requirements IF (a) they are currently registering, (b) under supervision or incarcerated, OR (c) if the offender re-enters the system because of a new conviction whether or not the new crime is a sex offense. • Requires states to have a failure to register offense on the books and provide a criminal penalty for a “maximum term of imprisonment greater than one year.” The Adam Walsh Act (AWA) exposed Congress relied on faulty data to justify AWA’s passage Assertion: All people who are convicted of a sex offense will do it again. Research: The Bureau of Justice Statistics tracked 272,111 individuals, including 9,691 people convicted of sex offenses, for three years following their release in 1994. Within the three-year time frame, 95 percent of the people convicted of sex offenses in the study remained arrest free. Assertion: Registries can protect children from sexual violence by strangers who are the biggest threat to children. Research: A study using FBI Uniform Crime Report data between 1991 and 1996 showed that 34 percent of youth victims (0-17 years old) were sexually assaulted by a family member and 59 percent were assaulted by acquaintances. Seven percent of youth victims in this study were assaulted by strangers. The AWA imposes a burden on already stretched state budgets. Ohio determined that the cost of implementing new software to create a registry would approach a half million dollars in the first year. • Installing and implementing software alone would cost $475,000 in the first year. The software would then cost $85,000 annually thereafter for maintenance. • If Ohio chose not to implement AWA, the state would lose approximately $622,000 annually from its Byrne funds. However, the total cost of software, certification of treatment programs, salaries, and benefits for new personnel would likely exceed the lost Byrne funds. Virginia conducted a comprehensive cost analysis and determined a total cost of more than $12 million for the first year of compliance with the registry aspect of the AWA. • The first year of implementing AWA would cost the Commonwealth of Virginia $12,497,000. This figure would include the cost of hiring 99 new staff people, implementing new technology and increasing the number of people on the registry by approximately 8,000 individuals. The AWA places significant burdens on law enforcement. Spending so much time tracking down people for failing to register and making sure that information in the registry is accurate overburdens law enforcement and can take away precious time and resources from more effective crime-fighting strategies like educating communities about effective ways to prevent sexual violence. • In Texas, the number of registerable crimes has grown from four to 20 since the enactment of the first registration laws in 1991, with approximately 100 new people added to the registry each week. • In 2003, San Jose, California, spent $600,000 to dedicate seven staff people to monitoring 2,700 people who are required to register. • In Michigan, as of August 2004, two full-time employees manage information and records for people convicted of sex offenses, but according to a state audit, the state’s sex offender registries still contain inaccurate and incomplete information that may give the public a false sense of security. The AWA needlessly targets children and families. • Numerous stories publicized in the media document youth as young as age 6 being labeled a sex offender for behaviors such as hugging or kissing other youth. • In most states, intercourse with a child under the age of 14, 15, or 16 is considered sexual assault regardless of consent. However, according to the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, slightly more than three-quarters of youth in the survey reported having had sexual intercourse. Of those youth, more than 80 percent reported having had sex by age 15.71 Thus, the youth reporting having engaged in sex by the age of 15 would be guilty of committing a sex offense. • Youth rarely eroticize aggression and are rarely aroused by child sex stimuli. Most youth behavior that is categorized as a sex crime is activity that mental health professionals do not deem as predatory. The AWA needlessly targets children and families. Recidivism rates of youth who commit sex offenses are low A 2002 review of 25 studies concerning juvenile sex offense recidivism rates reveals that youth who commit sex offenses have a 1.8 — 12.8 percent chance of re-arrest and a 1.7 — 18.0 percent chance of reconviction for another sex offense. Comparatively, in a 2005 study of 27 states’ youth recidivism rates conducted by the Virginia Department of Juvenile Justice, a study in 2005 found that 55 percent of youth were re-arrested within one year and 24 percent were reimprisoned for any offense, not just sexual offenses. The AWA needlessly targets children and families. Registries prevent people who need treatment from seeking it. • According to Bruce Winick of the University Of Miami School Of Law, sexual predator and community notification laws may be providing a strong disincentive for people who commit sex offenses to plead guilty to their crimes and accept treatment. • Researchers have found that as the penalty for sex offenses has increased, it has become more difficult to initiate an intervention for sexual violence both before the behavior is brought to the attention of authorities and after criminal sanctions are imposed. The AWA needlessly targets children and families. Registering children means registering entire families Having a family member on the registry puts an extra burden on the family of a person convicted of a sex offense. • A study of 183 people participating in sex offense treatment in Florida found that about 19 percent reported that other members of their household had been “threatened, harassed, assaulted, injured, or suffered property damage” as a result of living with a person on the registry. • According to a 1996 study by Freeman-Longo, reports in New Jersey and Colorado suggest a decrease in the reporting of both incest offenses and juvenile sex offenses by victims and by family members who do not want to deal with the impact of public notification on their family. The AWA needlessly targets children and families. The very purpose of the juvenile justice system is inherently undermined by the AWA. The AWA increases the likelihood that youth will be on registries because it includes youth adjudicated in juvenile court of sex offenses, thus undermining a system which is designed to protect youth from the lifelong penalties carried by the adult criminal justice system. • The juvenile justice system acknowledges that youth are amenable to treatment. Youth involved in the juvenile justice system should receive more treatment and rehabilitative services than they would receive in the adult criminal system. The registry undermines rehabilitation by labeling a young person a “sex offender,” thereby stigmatizing the youth and closing available doors for services and treatment. • Registries and notification ostracize youth and disconnect them from support systems. The Annie E. Casey Foundation’s annual Kids Count data book keeps tally of “disconnected” youth (youth who are not working or in school) as a factor in child well-being. Youth who are connected to school or work are generally expected to have better life outcomes than youth who are not. The AWA compromises community safety. Registries encourage a disproportionate and inappropriate focus on registries and the people on them. Statistics from the Justice Department support the idea that the people on the registry are not likely to be the people who pose the greatest potential threat. • The majority of people arrested for sex offenses have never been previously convicted of a sex offense. In 2003, the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) reported that 86.1 percent of the people arrested for a sex offense had never been previously convicted of a sex offense and would therefore not already be included in the registry. Furthermore, another study by BJS found that of all the adults arrested for rape in 1997 (791,513), 3.6 percent were of people released from prison in 1994. In other words, people who had been previously convicted of sex offenses are not the majority of people arrested for sex offenses on a yearly basis. • People who are convicted of sex offenses are not likely to repeat the offense. The BJS found that 95 percent of people released from prison after serving time for a sex offense remained arrest free within three years. The AWA compromises community safety. Reliance on registries creates the illusion that parents can protect their children from sexual violence simply by checking an online database. • A survey of mental health professionals found that 70 percent of those surveyed felt that “a listing of sex offenders on the web would create a false sense of security for parents who might feel that they can protect their children simply by checking a web site.” • Despite registry requirements and stiff penalties for not registering, registries are often inaccurate and out of date. • In 2006, Dallas Morning News found that 18 percent of Dallas County registrants either had incorrect addresses listed or never lived at the address listed. • In 2005, a Virginia man sued a private registry management company for falsely listing his name on a registry of people convicted of sex offenses. Another suit was filed against a neighbor for defamation. The company managing the registry does not verify information before posting it online. The AWA compromises community safety. Registering people for consensual, nonviolent, and statutory offenses overloads the registry and distracts the public. Furthermore, not every person on a sex offender registry has committed rape or a sexual offense against a child. Human Rights Watch reviewed statutes in all 50 states and found that a sex offense is defined differently in different states. The Adam Walsh Act (AWA), the newest piece of federal legislation related to registries, is designed to represent the minimum offenses that are registerable, thus the law is likely to encourage states to further expand the offenses for which people must register. At the time of the publication of the Human Rights Watch report, the following offenses require registration: • • • • Adult prostitution-related offenses (five states) Public urination (13 states, two limit registration to urination in front of a minor) Consensual sex between teenagers (29 states) Exposing genitals in public (32 states; of those, seven require the victim to be a minor). Recommendations: Federal and State Policy 1. Congress should repeal the section of the Adam Walsh Act that mandates the registration of youth under age 18. 2. States should refuse to put children on public registries. 3. Assess the effectiveness of sex offense registries and community notification on a national or state scale. 4. Reframe the problem of sexual violence from a criminal justice issue to a public health issue. 5. Determine how money spent maintaining sex offense registries and notifying communities might be better used elsewhere. 6. Evaluate the effectiveness of responses to sexual violence. 7. Assess the public safety impact of registries on communities. Recommendations: Local and Community Strategies 1. Educate the public about the realities of sex offenses 2. Educate the public on ways to increase personal safety 3. Provide resources to families who may be worried about inappropriate behavior 4. Provide training to teachers to help identify and distinguish between appropriate and concerning behavior State Legislation or Statute Alaska Arizona Submitted to SMART Office? Status as of September 2008 Alaska has not submitted any SORNA legislation and has just recently appointed an AG in the Department of Law to analyze the situation and make recommendations regarding whether or not (and how) Alaska will implement. Awaiting the SORNA final guidelines before drafting legislation. SB 1628 (passed April, 2007) Requires youth sex offenders to only be placed in treatment programs of similar age and developmental maturity level; requires a court hearing for any youth prosecuted as an adult to determine if youth should be transferred to juvenile court.; allows for an annual probation review hearing for youth sex offenders under age 22 who are in the adult system; allows transferred youth to be removed from the registry. California Considering costs, no legislation yet. Colorado A compliance committee made up of all the stakeholders is currently studying what it would take to implement AWA in CO. Doing a cost-benefit analysis of implementation and then will make recommendations to the Governor's office and legislature. There has been no legislation run or passed as of yet and we don't anticipate any in 2008. Delaware SB 60 Passed compliance legislation. Wholly adopted SORNA provisions. State Florida Legislation or Statute SB 1604 HB 665 Submitted to SMART Office? Georgia Hawai’i Illinois Kansas Submitted some policies such as the website, and some statutes, but has not passed legislation or submitted a full compliance package. Status as of September 2008 from the Association for the Treatment of Sexual Abusers Mostly adopts provisions of the SORNA, but not retroactive prior to July 1, 2007. So busy with their state residence restriction and other bills that they haven’t addressed the SORNA yet. Will be addressing SORNA but most likely not the juvenile piece. A work group, the Sex Offender Registration Team (SORT), is in place to study the possibilities for SORNA implementation. 7/17/08 update : legislature and the AG set up committee to evaluate the impact of SORNA, it will report back to the legislature prior to the opening of the 2009 session in midJanuary. SORNA implementation on hold for now. SB 121 passed in 2007 which challenges juvenile provisions of the SORNA: allows juveniles to petition to be removed from registry after a full hearing, 2 years for misdemeanor offense; 5 years for a felony offense Working on substantial legislative changes to come closer to compliance with SORNA. The state attorney general, based on information provided by the state’s Offender Registration Working Group, will not pursue the adult retroactivity portion or the juvenile requirements of the SORNA. Kansas will exceed SORNA’s registration requirements by having all sex offenses except for sexual battery register for life. Sexual battery will require a 15-year registration. Also, ALL offenders will be required to report in person quarterly. State Louisiana Legislation or Statute HB 970 R.S. 15:540 et seq Maine Maryland Proposed: SB24 Passed: SB59/HB18 Failed: SB 629/HB 76, SB1538, HB1450 Submitted to SMART Office? Yes; not in compliance. Status as of September 2008 from the Association for the Treatment of Sexual Abusers SMART Office responded: LA not in compliance and must change state codes regarding sexual assault to be in compliance. Also, tiering has to be fact-based rather than based on elements of the state offense. Also said LA not in compliance vis a vis tribal nations. Supreme Court ruled that retroactivity did not violate expo facto. United States Supreme Court is set for argument on Wednesday, April 16, 2008 regarding Patrick Kennedy v. a Jefferson Parrish sex offender on death row. Legislation pending to remove offenders from the registry for some offenses committed between 1982-1992. Also pending in the courts five challenges to the entire registry based on Doe v District Attorney et al, 2007 ME 139, a decision of the Maine Supreme Judicial Court issued last fall that called into question the constitutionality of registry based on state constitutional issues. The matter has been remanded for hearing. The state’s Criminal Justice Committee has put off consideration of whether or not to comply with Adam Walsh until next session (starting January 2009). Currently, no juvenile is included on the ME registry unless they have been bound over as an adult. SB59/HB18: State's sexual offender registry include the registrant's former names, electronic mail addresses, computer log-in or screen names or identities, instant-messaging identities, and electronic chat room identities used by the registrant. The bills also add (1) a copy of the registrant's valid driver's license or identification card; and (2) the license plate number and description of any vehicle owned or regularly operated by the registrant as items that must be included in a registration statement. State Legislation or Statute Submitted to SMART Office? Status as of September 2008 from the Association for the Treatment of Sexual Abusers Massachusetts MA has not decided on strategy yet, but are leaning towards compliance. No forward movement yet at the legislative side (that we know of). Several state constitutional issues have been identified as counter to the provisions of the SORNA, including the right of sex offenders to a due process hearing to determine risk level. Michigan The MI Senate had legislation introduced for compliance early on, but it didn’t go anywhere.With final guidelines will likely move in a definitive direction. The House has created a subcommittee to address existing registry issues and SORNA compliance but no bill has yet been introduced. Minnesota There are no plans at this time to introduce AWA-related legislation in the 2008 session. Passed SORNA compliance bill but it does not address retroactivity, nor is it in compliance as far as the requirements re: juveniles. Mississippi HB 1015 Submitted compliance package but it was not approved. Missouri SB 714 Passed SORNA compliance bill March 2008. Montana SB 156 SB 156 passed in early 2007 addresses some aspects of the SORNA compliance, but not all. Next legislative session is just before the July 2009 substantial compliance date. No SORNAspecific legislation has been drafted yet. June 11, 2008 decision in ’s US District Court (Waybright v. ) that SORNA is unconstitutional. State Nebraska Legislation or Statute LB 957 Nevada AB 579 New Hampshire HB 1640 New Mexico New York Submitted to SMART Office? Compliance package submitted to the SMART Office. Submitted their compliance package to the SMART Office. No answer yet. Not yet. Status as of September 2008 from the Association for the Treatment of Sexual Abusers AB 579 was passed May 31, 2007, enrolled on June 1, 2007, approved by governor on June 13, 2007, and codified in Chapter 485 of the NRS on June 14, 2007. Became effective July 1, 2008. NV appears to be closest to substantial compliance of all the states that have passed compliance legislation. On June 24, 2008, NV ACLU filed a federal lawsuit asking for a temporary stay in the law. July 9, 2008: HB 1640 passed by NH legislature and signed by governor. The law reworks state's registration system by categorizing the levels of sex offender crimes into three tiers. Law takes effect January 1, 2009. NM will not attempt to pass AWA legislation until January, 2009. Uncomfortable with the juvenile and retroactivity provisions of the Proposed Guidelines and have provided letters to DOJ on two occasions about this. Otherwise, NM appears to already be approximately 80% compliant. Many NM state officials are adamantly opposed to the juvenile provisions.Will be difficult for legislature to enact legislation providing for substantial compliance if DOJ maintains its strict reading of AWA. Has not yet determined whether it will comply with the AWA requirements. NY may not be able to achieve compliance because juvenile records are expunged. Concerned with the cost of implementation. State Legislation or Statute Submitted to SMART Office? SB 10 Not yet. North Carolina Ohio Status as of September 2008 from the Association for the Treatment of Sexual Abusers HB 933 (Jessica’s Law) introduced in short session. It increases 10 year registration to 30 years with a petition process at 10 years. If HB 933 is enacted, NC will have 2 tiers: 30 years and life. HB 933 changes 10 day registration/verification of registration to 3 business days. Attempt at compliance with AWA. Senate and House conference committee members appointed to work out differences between House and Senate versions of that bill; no action since appointments on 7/8/08. Implemented SORNA compliance legislation as of 1/1/08. Ohio Supreme Court ruled in favor of retroactive application of original SORN law, saying that SO classification is remedial, not punitive. State AG and legislators relied exclusively on that case to dispute constitutional claims. Ohio Criminal Sentencing Commission voted unanimously to recommend against retroactive application (but didn’t testify). SB 10 is retroactive, but not “super retroactive”. SB 10 was amended to greatly limit the juveniles who will appear on the Internet registry. Only juveniles transferred to adult court or designated “serious youthful offenders”. It includes only 2–3% of juvenile sex offenders in DYS. In Oct. 2007, direct action filed in Ohio Supreme Court. Challenge retroactive application of SB 10: violates separation of powers, ex post facto, due process, double jeopardy. The case ultimately dismissed. State Oklahoma Legislation or Statute HB 1760 went into effect November 1, 2007. Submitted to SMART Office? Yes; did not achieve substantial compliance Oregon Pennsylvania Texas Utah HB 492 Virginia SB 590 Washington Not yet. Status as of September 2008 from the Association for the Treatment of Sexual Abusers Under HB 1760 5,500 SOs were reclassified and almost 80% of them have been reclassified as Tier III offenders. The legislature considered HB 3159 to achieve further compliance. Earliest legislative session to address SORNA will be Jan 2009; right now looking at the financial impact of implementing the SORNA; legislative concepts are not due from state agencies until later in 2008.Will be filing for one-year extension in April 2009 as session does not end until July 2009. PA has introduced a SORNA compliance-related bill, SB 1130, but it doesn’t address much of what needs to be addressed to come into compliance. Will not address the SORNA until the Jan 2009 session. Had a bill in the 2007 session of the legislature that would have brought TX into partial compliance. HB 492 is a sex offender bill passed in 2008that addresses some of the SORNA requirements, but contravenes others, e.g. requires reporting of changes of residence, work, education institution, vehicle, and other information within three business days rather than five days; but requires registration every six months, rather than every year as is currently required by the UT registry Passed by the VA Assembly in its 2008 session. Attempt to meet substantial compliance but some question as to its success. Formed Sex Offender Policy Board in July 2008 How to contact us Justice Policy Institute 1003 K Street, NW Suite 500 Washington, DC 20001 202-558-7974 info@justicepolicy.org www.justicepolicy.org The accompanying guide for advocates, policymakers, and the media can be found at: http://www.justicepolicy.org/images/upload/08-11_BRF_WalshActRegistries_JJ-PS.pdf