9 Herling Edited

advertisement

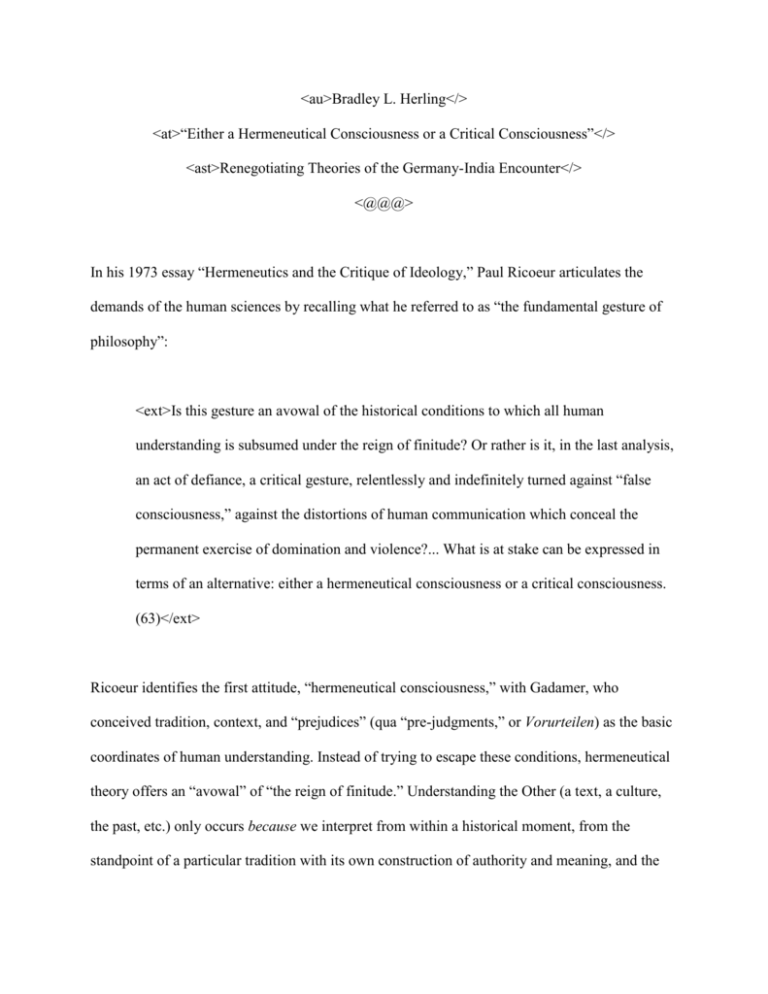

<au>Bradley L. Herling</> <at>“Either a Hermeneutical Consciousness or a Critical Consciousness”</> <ast>Renegotiating Theories of the Germany-India Encounter</> <@@@> In his 1973 essay “Hermeneutics and the Critique of Ideology,” Paul Ricoeur articulates the demands of the human sciences by recalling what he referred to as “the fundamental gesture of philosophy”: <ext>Is this gesture an avowal of the historical conditions to which all human understanding is subsumed under the reign of finitude? Or rather is it, in the last analysis, an act of defiance, a critical gesture, relentlessly and indefinitely turned against “false consciousness,” against the distortions of human communication which conceal the permanent exercise of domination and violence?... What is at stake can be expressed in terms of an alternative: either a hermeneutical consciousness or a critical consciousness. (63)</ext> Ricoeur identifies the first attitude, “hermeneutical consciousness,” with Gadamer, who conceived tradition, context, and “prejudices” (qua “pre-judgments,” or Vorurteilen) as the basic coordinates of human understanding. Instead of trying to escape these conditions, hermeneutical theory offers an “avowal” of “the reign of finitude.” Understanding the Other (a text, a culture, the past, etc.) only occurs because we interpret from within a historical moment, from the standpoint of a particular tradition with its own construction of authority and meaning, and the practice of interpretation unfolds in dialogical fashion, allowing a gradual accumulation of everadjustable truths. Misapprehensions, it should be said, are affirmed as part of this dialogical process as the interpreter “reintegrate[s] misunderstanding into understanding by the very movement of question and answer” (83). In his essay Ricoeur associates the opposing view, the approach of “critical consciousness,” with Habermas, though it surely evokes past modern masters of suspicions (Marx, Nietzsche, and Freud) and, by extension, more recent theorists such as Gramsci, Benjamin, and Foucault. According to Ricoeur, “critical consciousness” lodges a protest against the “reign of finitude,” often in the cause of lifting the veil on “the permanent exercise of domination and violence.”1 The “tradition” that dictates the expanse of our hermeneutical circle is in fact the product of underlying forces, like economic interest, sexual drive, or the will to power; criticism has the power to unmask these “ideologically frozen” dependencies (82), which is a crucial step in freeing ourselves from the repression, injustice, and exploitation that they often enforce. As a consequence, “critical consciousness” insists—in contrast with the hermeneutical model—that distortions in communication and understanding are “always related to the repressive action of an authority and therefore to violence” (83). Ricoeur’s scheme illuminates dynamics that have been at work within the humanities and social sciences for several decades. His formulations are particularly helpful, however, when we consider recent work on the encounter between European intellectuals and the cultural artifacts (texts and data) of non-Western, largely colonized lands. Within this broader frame, the postEnlightenment reception of South Asian culture, texts, and thought in German-speaking lands has emerged as a challenging area of investigation. And here too Ricoeur’s observations identify a significant theoretical rift in the scholarship, one that I plan to trace in this article. But I also aim to chart out some new territory. Indeed, by drawing bright lines between “hermeneutical consciousness” and “critical consciousness,” I wish neither to over-simplify nor to call for an either/or decision in our historical investigation of India’s place in the German imagination. In fact, Ricoeur himself questioned his categories almost as soon as he offered them: “Is it not the alternative itself which must be challenged? Is it possible to formulate a hermeneutics which would render justice to the critique of ideology, which would show the necessity of the latter at the very heart of its own concerns?” (63). Building upon my work on the early reception of the Bhagavadgītā among German intellectuals (figures like Herder, the Schlegel brothers, Wilhelm von Humboldt, and Hegel),2 I will offer suggestions regarding potential fusions of “hermeneutical consciousness” and “critical consciousness”—and also attempt to illuminate some new theory-driven pathways through the historical thicket of the Germany/India encounter. *<!>Please use an ornament rather than an asterisk<!> To begin, let us turn to the scholarship to discern notable examples of the approaches that Ricoeur has outlined. Where, first of all, do we find “hermeneutical consciousness”? Here we need to look no further than the influential work of the late great Wilhelm Halbfass. As a careful commentator on both Indian and Western thought, Halbfass devised an intellectual framework for comparative, cross-cultural philosophy, and, to put it in a nutshell, it was hermeneutical in orientation. Halbfass’s influential text India and Europe (1988) is in fact a monument to “hermeneutical consciousness”: to get a handle on the meaning of comparative philosophy in the present, one must first understand the tradition that forged it. India and Europe is precisely that genealogical account. In this work, Halbfass rarely hesitates to highlight moments when Europeans—and Germans in particular—misconstrued and misrepresented South Asian worldviews, but in his hands these misapprehensions consistently become Gadamerian “prejudices.” By carefully identifying the intellectual context from which limited judgments and faulty representations sprung, Halbfass constructs a historical narrative within which there was always some interpretive progress being made, however sporadic. India and Europe consistently reflects this hermeneutical sensibility, in discussions of Herder (72–73), Friedrich Schlegel (79–80), Hegel (96–99), Schelling (102–03), Schopenhauer (116–17), and many others. As Halbfass puts it, in a decidedly Gadamerian formulation: <ext>There is certainly no coherent history of [the] European search for India. Yet, there is an identifiable historical path leading to the situation of modern Indological research and of intercultural communication. It is a process which accompanies and reflects the development of European thought in general—a process in which Europe has defined and questioned itself, and in which misunderstandings and prejudices may be as significant as the accumulation of factual truth and correct information. (434–35)</ext> In a limited sense, this “process” of understanding led to a more faithful picture of Indian culture and thought, but Halbfass articulates another theoretical proposition that is central to the hermeneutical approach: gaining better knowledge about the Indian Other in Germany depended on the Indian Other becoming a genuine challenge to the self-understanding of German intellectuals; they were prompted to become Other to themselves. In no other way could idiosyncratic distortions and obviated prejudices have become dislodged. And according to Halbfass, they often did in early nineteenth century Germany, allowing Indian thought to come into focus slowly but surely. It must be noted that Halbfass’s account contains its own share of “critical consciousness.” The last part of India and Europe, for example, registers a deep concern about the “Europeanization of the earth,” a cultural/philosophical force that accompanies the ascendancy of European power (166–70, 439–42). Within this frame, Halbfass’s reading has both a nostalgic aura and a polemical edge; he charts the gradual expulsion of Indian thought from the canon of philosophy during the course of the nineteenth century and then discerns the impact of that legacy among his contemporary philosophical colleagues. By highlighting the relative openness and evident vigor with which late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century German intellectuals investigated Indian worldviews, a provocative argument emerges: if these figures (even someone like Hegel!) could take the intellectual content of Indian culture seriously, despite the limited information available to them, then why can’t today’s philosophers? And shouldn’t we be concerned about this parochialism, when it seems to mirror the globalizing hegemony of “the West”? Despite this critical edge, Halbfass’s Gadamerian apologetics might strike some readers as a bit quaint—and, indeed, perhaps dangerously naïve. After Said, we are urged to see the entirety of German intellectual discourse on India as part of a “Western style for dominating, restructuring, and having authority over” other cultures (Said 3), a style that was linked to the actual deployment of European colonialism. To this extent, Said’s Orientalism is a quintessential expression of “critical consciousness,” and it laid out the contours of a new and distinctive approach to the Germany/India case. One of the earliest and still most notable attempts to apply Said’s argument to the European study of South Asia appears in Ronald Inden’s work Imagining India. Drawing upon Freud, Gramsci, and Foucault (as well as Said), Inden argues that a master discourse circumscribed the interpretation of Indian culture and society in the modern West, transforming Orientalist knowledge into cover for European power. This scheme drew on a broad assumption in the post-Enlightenment episteme, namely that human beings, their cultural forms, and their social institutions could be reduced to stable, essential elements that undergird shifting “surface phenomena”—including “the actions of transient, historical agents” (Inden 263). Capturing and then dogmatically reasserting these tropes enabled the Western interpreter to get a fix on the imagined essence of the Indian Other, at the expense of reality; a world constituted by the dynamic overlapping of cultural and social institutions, and by the complex activities of actual living, breathing, thinking agents. According to Inden, two essentialized conceptions came to dominate the European study of India during the nineteenth century: caste and the imagination. German scholars and intellectuals played a major role in constructing and reinforcing these ideas, despite taking up divergent perspectives on them. Friedrich Schlegel’s Romanticist “positive Orientalism,” for example, led him to a relatively favorable view of caste; it was perhaps but “a primitive example of civil society” (69). Yet caste was a necessary touchstone in his discussion of India, contributing to Hegel’s powerful final word on the matter, as summarized by Inden: <ext>[Caste] has become, in Hegel’s pages, the necessary and distinctive nucleus of India, logically integral to the whole of Indian civilization. It has ... become the substantialized agent of Indian history, from the time of its appearance down to the present. To be sure, it gave India a brief glint of sunshine, but then petrified, causing India itself to spend the rest of time as the passive recipient of acts by other, more assertive essences from the West. (71) </ext> Schlegel also wrangled with Hegel over the nature and value of the imagination. For Schlegel, the Romantic, the imagination had a powerful synthesizing function, and thus its expressions, at least in theory, deserved to be honored. But Hegel subordinated imagination to reason because it intermingles with the sensual—and then detaches itself from reality in impassioned flights of fantasy (94). Allowing the imagination free play could lead to submergence in a dreamy, undifferentiated cloud (“illusionary pantheism”), or it could result in seeing more in the natural world than one should—maybe even gods (“nature religion”). In Hegel’s reading, both of these eventualities unfolded within the Indian worldview, and its center could not hold. The crucial point, according to Inden, is that both the Romantic and the Hegelian agreed that “the Indian mind” was essentially constituted by the irrational imagination. For the former, this could be seen as positive; perhaps India was a source of a primordial aesthetic revelation that would bring renewal to tired old Europe. For Hegel, this essence was decisively negative. Despite these differences, however, Inden suggests that both thinkers reinforced the same vision, the same essential interpretive touchstones, reinforcing a broader European intellectual discourse on India. Inden’s form of “critical consciousness” is most provocative when he attempts to dramatize the impact of this discourse. For example, to insist that India is a) essentially a caste society, whose parts are radically and inherently disparate and scattered, and b) that it is a also land of the dreamy imagination, where rationality and pragmatism have not matured, is equivalent to saying, in no uncertain terms: India needs a firm, guiding hand from outside to make sense of things—a European hand. As Inden writes, “[Indology] actually fashioned the ontological space that a British Indian empire occupied. Its leaders would ... inject the rational intellect and world-ordering will that the Indians themselves could not provide” (128). At the same time, this discourse was not just about foisting reductive essences on the Indian Other; rather, “India was (and to some extent still is) the object of thoughts and acts with which this [Western] ‘we’ has constituted itself” (3). In other words, positioning India as a realm of caste allowed European observers to define and bolster their own vision of individualism and community. And reducing the “Indian mind” to irrationality and imagination was a mode of ejecting these foibles from the rational, pragmatic Western Self, while also keeping them on hand as a projected part that has been lost, a potential object (particularly for the Romantic) of a nostalgic quest. On both fronts, the central dictate of Inden’s “critical consciousness” comes through loud and clear: Western scholarly discourse on India played an important role in the construction of cultural identities and political structures that effaced the lived reality of the colonial subject, while simultaneously narrowing the capacity for self-understanding in the socalled West. How are we to measure these different approaches, hermeneutics and criticism, in relation to each other? How should we decide whether one theory is right, and the other is wrong? Certainly the body of scholarship on this material has advanced well beyond these two venerable texts, India and Europe and Imagining India, so perhaps the answer lies in the concreteness of the analysis—in the devilish details of careful intellectual history.3 But as I illustrate in the next section, historical specificity does not necessarily resolve the tension between these two approaches. In fact, it may only exacerbate the problem. *<!>Please use an ornament rather than an asterisk<!> One of the most impressive intellectual achievements of the early part of the nineteenth century was Wilhelm von Humboldt’s two-part analysis of the Bhagavadgītā from 1825 and 1826.4 Here Humboldt puts on a remarkable display of erudition: he immersed himself in the language of the text, learned as much as he could about its philosophical backdrop (from Colebrooke’s newly published treatises on the schools of Indian philosophy), and allowed his subjectivity to be engaged in the interpretive process, going so far as to engage his empathetic imagination, trying ideas from the Gītā on for size.5 All of this was premised, one might argue, on a high degree of open-mindedness that allowed Humboldt to take the text seriously as an object of both philosophy and philology. But a proponent of “hermeneutical consciousness” might remind us that Humboldt’s investigations were themselves conditioned by a prejudicial structure, one that had been authorized by his intellectual tradition and carried forth by the learned community to which he belonged. So Humboldt’s analysis of the Gītā was the culmination of a gradual process begun by Johann Gottfried Herder some 35 years earlier. When Herder read Charles Wilkins’ English translation of the Gītā in the late 1780s, he had a place ready for it, an interpretive position that imagined it as a product of the “cradle of humanity,” an archaic expression of the “mind” of India that combined poetry, philosophy, and religion in a direct synthetic whole. It was the kind of text that suggested the possibility of cultural rebirth in modern Germany, one that asserted the validity of holistic philosophical doctrine, a vitalist pantheism that could unify the forces that modernity had split asunder. This interpretive structure, which circumscribed the level of hermeneutical engagement Herder could have with the text, along with his exclusive reliance on Wilkins’s English translation, led to a distorted reading. Yet these prejudices also promoted a relatively sophisticated textual encounter. For example, in light of his own philosophical experimentations in the wake of the Pantheismusstreit,6 which are most vividly expressed in the pages of Gott Einige Gespräche (1787), Herder’s “translations” of excerpts from the Wilkins rendering tend to isolate the seeming contradiction between a pantheist or monistic metaphysics and the significance of action. This was one of the main objections to pantheism in Herder’s philosophical context, and it guided his reading of the Gītā. So, while he was attracted to the possibility of synthesizing knowledge and action, Herder implicitly raised questions about why any given action has moral significance, if one had attained realization of the oneness of all things. This point, the proponent of “hermeneutical consciousness” would likely assert, is an entirely viable line of inquiry in dealing with the text. For the present purposes, however, the more important result of Herder’s analysis of the Gītā—and of the Indian worldview in general—was that it conditioned the next phase of the discussion. Friedrich Schlegel inherited many of the hermeneutical presuppositions that Herder had clarified and championed. When Schlegel turned to actual Indian texts in the early years of the nineteenth century, he was hoping to see a “new mythology” arise in their pages, one that would provide the rationale for a powerful Romantic synthesis.7 Once again, pantheism was a central concern guiding Schlegel’s line of hermeneutical questioning. However, the historical framework laid out in Über die Sprache und Weisheit der Indier (1808) also led him to a differentiate philosophical layers within the text, which was a significant advance—even if his intent was ultimately to devalue the Gītā. The uneasy interpretive legacy that Schlegel left when it comes to the interpretation of South Asian language, culture, and philosophy is now well documented. His Frühromantik rhapsodies placed India solidly within the realm of “reverse teleology” that for Gadamer characterized Romanticism, a backwards teleology that located its prized objects (in this case the “wisdom” of India) in some irreal, primordial past (Gadamer 201). The present of these cultural objects, in contrast, could only be read as a dim, degenerated outgrowth of the “Golden Age.” This scheme persisted in Über die Sprache, but the narrative of degeneration became all the more pronounced. The Gītā, for example, was in the end a bearer of “pure pantheism” (F. Schlegel, Kritische Ausgabe 8: 249), but pantheism was no longer a good thing; instead, it was where the degeneration of Indian wisdom had terminated. Surprisingly, it was also where contemporary Europe found itself, in the thrall of idealism.8 Thus Schlegel’s contentious relationship with his own cultural and intellectual context ultimately distorted his hermeneutical frame for interpreting South Asian texts, and after 1808, he largely left them behind. But once again, it could be argued that Schlegel’s contributions allowed for a further expansion of the interpretive capacity of his intellectual community. We must take note of the lengthy excerpts from the Gītā (and other texts) that are appended to Über die Sprache, for example. These are powerfully wrought, German verse translations of the original texts, the product of several years of intensive study in Paris. As these excerpts show, the prejudicial assumption that Indian texts should be studied like those of Greece and Rome had proved remarkably productive—as had Romantic “Indomania,” based on a misguided “reverse teleology.” Classicist philological sensibilities and Romantic enthusiasm, which persisted beyond Schlegel’s own disillusionment, were in fact crucial elements in the construction of a viable hermeneutical location for the new discipline of Indology. This frame of reference began to emerge most decisively in the work of Franz Bopp and August Wilhelm Schlegel. In the present context, Schlegel’s full Latin translation of the Bhagavadgītā from 1823 draws our attention. Here the translator refrains from non-philological commentary; he resists the temptation to impose some cultural or philosophical agenda on his rendering. This move reveals that a new interpretive structure is at work in the examination of Indian sources: that of philological science.9 The hermeneutical issues, the interpretive questions that prompted response and further inquiry within this discursive community, were concentrated within the language itself; they resided within the translator’s choices, and these become the more technical sites of inquiry that anchored the practice of interpretation in the era of Indology. This is not to say that A.W. Schlegel’s Gītā was merely a transparent, technical product of German philology. His choice of Latin was designed to say something, for example, namely that the translation, a shining example of German intellectual preeminence, was designed for the consumption of learned Europe as a whole. This target language also positions the text as archaic—and worthy (through the translator’s artifice) of a place next to the authoritative works of the Classical world. I should also note that the individual choices within the translation were at times enigmatic, a fact that was not lost on the European audience that Schlegel had hoped to dazzle.10 And so, at this moment, after following the German career of the text that he devoted so much attention to in the mid-1820s, Humboldt becomes the inheritor of an accretion of hermeneutical prejudices that allow him to achieve some remarkable exegetical work. Did he retain some of the early Romantic assumptions carried forth by figures like Herder and F. Schlegel? Yes: he suggested that the Gītā did in fact present a kind of synthetic, imaginative whole, a vision that combined the philosophical and the aesthetic. But it is also clear that philological prejudices, which led to many fruitful avenues of reception, tempered the excesses of bygone enthusiasms and led ultimately to a measured account that is noteworthy even to this day. The analysis I have just presented provides a breezy but not implausible case for the approach of “hermeneutical consciousness.” I have based it on a relatively specific historical testing ground: the early reception of the Gītā in Germany. While it is tempting to evaluate it on its own terms, let us turn instead to a rejoinder from “critical consciousness” and, following Ricoeur’s schema, highlight the distinctiveness of these two theoretical approaches. There are, in fact, so many openings for an interpretation in light of “critical consciousness” that it is difficult to know where to start. From the Saidian perspective, for example, all of these efforts to understand the Gītā are relentlessly self-obsessed: these readings only refer to each other and themselves; they compose a body of enunciations that are designed to uphold the European sense of superiority. In each phase, we find a brand of intellectual imperialism: in the Romantic “reverse teleology” (the “positive Orientalism,” to use Inden’s phrase), which proposes that India’s greatness is only in its bygone past, and now the artifacts of that past can only be recovered by the ingenuity of the German/European; in the emphasis on Indian pantheism, which is ultimately obtuse and amoral, requiring the tutelage of a more discriminating European intelligence; in philological science itself, which represents the ascendancy of the Orientalist’s ability to organize, control, and categorize another culture’s texts. Instead of working through all the details of this critique, however, allow me to choose an example that supports a more direct case for “critical consciousness.” In an 1849 publication by the Wesleyan Mission Press in Bangalore, we find Wilkins’s original English translation of the Bhagavadgītā, A.W. Schlegel’s Latin rendering, and a number of essays—including an English translation of Humboldt’s 1825–26 Berlin lectures on the text. In his introduction, the Reverend G.H. Weigle glosses the Humboldt treatise as follows: <ext>Should these pages find any readers among young Hindoos, it is hoped that they will acknowledge the perfect fairness and deep research, with which the learned author conducts his disquisition; and that they will learn from him an art in which their own ancestors were certainly not backward, that of thinking. And if they think aright, and examine the holy books of the Christians, with a fairness similar to that with which one of their own is here investigated, they cannot remain in doubt concerning the value of either. (123)</ext> Weigle executes some classic colonialist strategies in this passage, strategies that “critical consciousness” is designed to detect and unmask. He promotes the value of India’s past, for example, but only in order to chide contemporary “Hindoo” youth with a subtle and patronizing rebuke. The “young Hindoos” themselves are not able to return to their own venerable, thoughtful past: that will take the enlightened mediation of great European scholars like Humboldt. At the same time, Weigle uses Humboldt’s methodological openness as a tool for proselytizing, for if Humboldt in his far-flung land could take the Gītā seriously and study it with care, then why can the natives not do the same with the Christian Bible? Thus even hermeneutical openness is an expression of power; it can easily be brandished before the colonial subject as a marker of European cultural superiority. This is perhaps the very nature of a hegemonic, imperialist discourse: it manages to convert both empathetic engagement and vigorous protest into fuel for its own persistence. In instances like this, it must be admitted that the ghosts of Foucault and Said put a real scare into the Gadamerian model of hermeneutical consciousness. *<!>Please use an ornament rather than an asterisk<!> What are we ultimately to conclude regarding the two theoretical approaches outlined in our investigation? A very big question is actually at issue here: how should history, and specifically this history, be done, and assuming that it can be done faithfully, what conclusions should we draw from it? In this particular instance, we are asking: what is it, exactly, that Humboldt did when he wrote his remarkable treatise on the Gītā? Perhaps this is merely a question of emphasis: maybe Humboldt’s text is both a success of the hermeneutical process, a momentary “fusion of horizons” (to use Gadamer’s phrase) that contributed to later interpretive efforts, and a product and object of Orientalist, colonialist discourse, destined to bolster an imbalance of power between colonizer and colonized. Yet we cannot so quickly discount the genuine tensions between these two perspectives, tensions that seem to render them mutually exclusive. While “hermeneutical consciousness” takes the individual encounter with a text (or with another person, a conversation partner) as its model for the act of understanding that which is foreign, and thus affords Humboldt a high degree of interpretive freedom, it also tells us that his tradition guided his questioning. Humboldt’s hermeneutical engagement with the Gītā was only meaningful to the extent that it was authorized by his context, and if his context was surreptitiously twisted by deeper forces, this flash of understanding was in the ultimate service of something larger and perhaps more nefarious. The ease with which Reverend Weigle appropriated the text is the tip-off on this account. Even Humboldt’s openness, which is the premise of successful acts of interpretation in Gadamer’s scheme, emerges as part of a larger discourse of European power. Yet the advocate of hermeneutics has a response: the individual German interpreters like Humboldt had no way out of a monolithic discourse that was anonymously designed to control and patrol India with its intellectual practices. To this point, we recall one of Said’s most famous (or infamous) declarations from the pages of Orientalism: <ext>It is therefore correct that every European, in what he could say about the Orient, was consequently a racist, and imperialist, and almost totally ethnocentric. Some of the immediate sting will be taken out of these labels if we recall additionally that human societies, at least the more advanced cultures, have rarely offered the individual anything but imperialism, racism, and ethnocentrism for dealing with “other” cultures. So Orientalism aided and was aided by general cultural pressures that tended to make more rigid the sense of difference between the European and Asiatic part of the world. (204)</ext> As this passage illustrates, the approach of “critical consciousness” has the tendency to leave aside differences between disparate national, local, and individual efforts at cross-cultural understanding. It also denies flatly that actual advances and progress occurred, despite considerable evidence to the contrary. Not everything can be reduced to the political and/or the economic; it seems sensible to remain open to the possibility that some Orientalist efforts escaped such interests and contributed to cross-cultural understanding. We might add that the approach of “critical consciousness” tends to see the Indian Other as silent and passive in the face of an overwhelming, all-powerful European discourse. “Hermeneutical consciousness,” in contrast, always reminds us that otherness, even if it is only embodied in a foreign text, always speaks, always resists, and always insists that the interpreter adjust his understanding—if he is brave enough to listen. Even denial and stubbornness in the face of cultural otherness is symptomatic of its disruptive potential. Despite these serious disjunctions between the two approaches, I am drawn to the prospect of a synthesis, and Richard King has proposed a succinct way to think about this possibility: <ext>it is necessary to combine Gadamer’s insights into the “historical situatedness” of the interpreter with an awareness of the ideological elements at play in both text and interpreter. Gadamer’s redemption of prejudice suggests that the interpreter, rather than suppressing his or her biases and agenda in the pursuit of scholarly neutrality, should, on the contrary, bring such prejudices to the fore. Such an approach involves an attitude of critical reflexivity towards one’s work. (King 80) </ext> In other words, hermeneutics and “critical consciousness” come together when we identify the genealogical critique of our categories, including the anti-Orientalist critique, with a foregrounding of the prejudices that have come down to us from within our tradition.11 This echoes Ricoeur’s suggestion that we “formulate a hermeneutics which would render justice to the critique of ideology, which would show the necessity of the latter at the very heart of its own concerns” (63). When we transform these suggestions for the present into a historical model, we derive an instructive corollary: we must be able to account for both interpretive progress and ideological retrenchment, sometimes in the very same object of historical inquiry, an object like Humboldt’s Gītā text. This is no mean task. I would argue that it requires a highly nuanced sociology of knowledge, one that reaches across the boundaries of intellectual history, comparative literature, and comparative philosophy and adds richness and texture to our theoretical vocabulary. For example, following the work of Bruce Lincoln, Dorothy Figueira, and George Williamson (and of course the venerable A. Leslie Willson),12 I have proposed that we begin by revivifying the old dialectic of “myth” vs. “logos” to distinguish and describe the prejudicial structures that we find in the work of intellectuals and their communities. “Myth,” according to Lincoln, is “ideology in narrative form” (147), and when framing their work, scholars have been utterly prone to constructing such mythic imaginaries when encountering the foreign and unknown (the Voltairean vision of India as the “cradle of humanity” is one such myth). Much of what is described by “critical consciousness” as the European discourse of intellectual imperialism, including the vast body of distorted representations and stereotypes, falls under this conceptualization of myth. But there also must be some room made for the possibility of refinements in understanding and logos is the name for the application of technique and method to the project of cross-cultural understanding (here the application of philological, exegetical tools to a text like the Gītā is an example). Can logos be overwhelmed by myth, distorted out of recognition by unsettling agendas and narratives? Certainly. Do esoteric and inaccessible logoi need myths to justify and popularize themselves to a learned (or not so learned) public? Yes. Can logos be taken up by mythic discourse and brandished before the real or imagined colonial subject? Of course. But is there something ultimately independent about scholarly technique and method that has at times yielded moments of cross-cultural understanding, even if there were great challenges to it? Without a doubt. I would also argue that we increase our attention to the way intellectual communities mediate myth and logos. Invoking Ludwik Fleck’s pioneering text Genesis and Development of a Scientific Fact (first published in 1935), I have proposed that we trace the “proto-ideas,” “conceptions,” “structures,” and “styles” of scholarly communities and their discourse. In the early construction of knowledge about the Indian Other by the German intellectual tradition, for example, we find that hazy “pre-ideas” and “conceptions,” often tied to broader scholarly myths of Indian culture, initiated the circle of interpretation. Through the process of more technically oriented inquiry (logos), these conceptions gained a level of firmness. Certain structures and styles became reliable modes of knowing. And some of these structures and styles were allowed to calcify, solidifying into slogans and clichés. The nature of these prejudices—and the basic tendencies of a scholarly community encountering something challenging and new, and foreign—inhibited the hermeneutical openness that should have allowed faulty assumptions to be corrected and refined. That the pantheism concept remained in play for so long in the interpretation of the Gītā, for example, supports the suggestion that it was one of these “structures” described by Fleck: it was a repeated scholarly touchstone, virtually a fetish, that took on a life of its own as a frame through which to view the foreign text. Here we address one consistent quandary for the “hermeneutical consciousness” proponent. Why do certain unproductive prejudices persist, even when intellectuals have the opportunity to put themselves into interpretive play with sources that are supposed to make them adjust and recalibrate their views? The answer is not always “power”: it sometimes has to do with the nature of intellectual communities themselves, which have their own distinct set of sociological dynamics and discursive practices. As a final point, I would also argue that this history needs to move much closer to the event of contact between European intellectuals and India. This means moving closer to the material conditions of possibility for cross-cultural encounter, and paying more careful attention to the scholarly practices that constructed India as an object of European knowledge. Halbfass, the purveyor of “hermeneutical consciousness,” admitted that his inquiry was intellectualist: “It seems to neglect the ‘real world’ of social, anthropological, economic, political, and military events and conditions” (xi). But we might ask whether “critical consciousness” has made much more progress drawing connections with the “real world.” Stemming from Said, it is assumed that critique of Orientalist discourse (or German intellectual discourse) always somehow speaks to these realities because of the assumption that all such discourse must be linked to the actual deployment of European colonialism. As I have already suggested, this is a faulty assumption; or, at the very least, it must be borne out by the historical research itself, in individual sites of inquiry. As a general rule, we might attempt to get beyond one of the most misleading, but largely neglected limitations of the Saidian brand of inquiry: it fixates on representations of India that were embodied primarily in statements about it. This methodological focus led Said to suggest that the “enunciations” (to use Foucault’s term) that made up the discursive formation called Orientalism only referred to themselves and never to a real, empirical Orient. There was inevitably a form of encounter, however, in the practices through which foreign texts were constituted, such that it was possible to make statements about their culture in the first place. Attention to the details of these textual practices, I would argue, disrupts the problematic assumption that Indian otherness offered no resistance to a supposedly insular, monolithic intellectual discourse that was invented to control it in Germany. Given the Foucauldian impulse behind the Said’s deployment of the “critical consciousness,” it is surprising that the “micro-physics” of Orientalism’s textual practices have rarely been explored.13 There are some notable exceptions of course. For example, in his essay on the 1820s debate about the Gītā between Humboldt and Hegel, Saverio Marchignoli claims that a basic matter of textual practice framed the discussion: whether the Indian work should be part of the “cultural canon” or not. Such debates had an immediate impact on the way German learned culture received and handled a text; it determined what texts would be produced and read, and how they would proliferate and become known as representative objects of the past, or of the other land. A thorough discussion of the practices of textual reception would go on to account for the full chain of transmission: the relationship between the native informant (e.g., the pandit) and the European intellectuals who learned native languages and then translated and published Indian texts; the process by which Indian texts were procured and transported to European centers of learning; and the method by which libraries identified, catalogued, and made these texts available such that they became recognizable to the German exegete. In my own work, by focusing on translation practices, I have admittedly remained relatively close to the surface of the European archive, but I would argue that when we look at translation carefully, against the specific backdrop of a German culture of scholarship, we take an important step forward in reconstructing the dynamics of the transmission of South Asian sources into the European episteme. To invoke Ricoeur’s dichotomy one last time, we can take up “hermeneutical consciousness” and think of a translation as an interpretive act that interrogates the original text with its approximations. We can also see it, in accordance with “critical consciousness,” as an act of intellectual/cultural mastery. My tendency has been to identify the degree to which German translations of Indian texts (on which so much depended) foreclosed and fixed cross-cultural understandings, rather than opening them to scrutiny. And yet, vigorous contemporary analysis of these renderings (analysis I am tempted to call deconstructive) also reveals how they confound themselves: how the supposed mastery of the European intellectual was disrupted by South Asian textual otherness before the Orientalist discourse could ever have imagined itself to be in control. I cannot claim to have thoroughly outlined a “third way” for scholarship on German Orientalism in this brief essay. Instead, we can only wait for this path to emerge as contemporary scholars continue to revisit this challenging layer of European intellectual history—but it is beginning to emerge. The last few years have seen complex institutional histories instead of diatribes driven by grand generalizations, careful estimations of the link between scholarship and colonialism, and an ever-expanding recognition of the sheer diversity of motives and aims among German intellectuals who took India as their object of study. In addition, we observe a persistent urge to move beyond statements about and representations of India, and into the specific contexts, intellectual practices, and material conditions that subtended them. In light of these developments, perhaps the “third way” is but a reassertion of careful intellectual history and incisive textual analysis. But it also must be grounded in a simple but powerful recognition: the German Orientalist understanding of India was never purely a function of power, nor did it always make progress; the truth resides somewhere between. <#><aff>Marymount Manhattan College</> <bmh>Works Cited</> <bib>Benes, Tuska. In Babel’s Shadow: Language, Philology, and the Nation in NineteenthCentury Germany. Detriot: Wayne State University Press, 2008. </bib> <bib>Figueira, Dorothy M. Aryans, Jews, Brahmins: Theorizing Authority through Myths of Identity. Albany: State University of New York Press, 2002. </bib> <bib>______. The Exotic: A Decadent Quest. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1994. </bib> <bib>Fleck, Ludwik. Genesis and Development of a Scientific Fact. Trans. Fred Bradley and Thaddeus J. Trenn. Eds. Thaddeus Trenn and Robert K. Merton. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1979. </bib> <bib>Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. New York: Routledge, 1979. </bib> <bib>Gadamer, Hans-Georg. Truth and Method. 2nd ed. Trans. Joel Weinsheimer and Donald G. Marshall. New York: Continuum, 1989. </bib> <bib>Germana, Nicholas. The Orient of Europe: The Mythical Image of India and Competing Images of German National Identity. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2009. </bib> <bib>Halbfass, Wihelm. India and Europe: An Essay in Philosophical Understanding. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1990. </bib> <bib>Herder, Johann Gottfried. God: Some Conversations. Trans. Frederick H. Burkhardt. New York: Veritas Press, 1940. </bib> <bib>Herling, Bradley L. “Epilinguistic Hypophecy: August Wilhelm Schlegel’s Latin Bhagavadgītā.” Epilanguages: Beyond Idioms and Languages. Ed. Pascale Catharine Hummel. Paris: Philologicum, 2009. 95–122. </bib> <bib>_____. The German Gītā: Hermeneutics and Discipline in the German Reception of Indian Thought, 1778–1831. London: Routledge, 2006. </bib> <bib>_____. “The Problem of Action in the Early German Interpretation of the Bhagavadgītā.” Mapping Channels between the Ganges and the Rhein. Eds. Joerg Esleben, Christina Kraenzle, and Sukanya Kulkarni. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2008. 82–106. </bib> <bib>Humboldt, Wilhelm von. “Ueber die unter dem Namen Bhagavad-Gîtâ bekannte Episode des Mahâ-Bhârata [I and II].” Gesammelte Schriften. Vol. 5. 1906; reprint, Berlin: Walter de Gruyter & Co., 1968. 190–232, 325–44. </bib> <bib>Inden, Ronald. Imagining India. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2000. </bib> <bib>King, Richard. Orientalism and Religion: Postcolonial Theory, India and ‘The Mystic East.’ London: Routledge, 1999. </bib> <bib>Kontje, Todd. German Orientalisms. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2004. </bib> <bib>Lincoln, Bruce. Theorizing Myth: Narrative, Ideology, and Scholarship. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999. </bib> <bib>Marchand, Suzanne L. German Orientalism in the Age of Empire: Religion, Race, and Scholarship. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009. </bib> <bib>Marchignoli, Saverio. “Canonizing an Indian Text? A.W. Schlegel, W. von Humboldt, Hegel, and the Bhagavadgītā.” Sanskrit and ‘Orientalism’: Indology and Comparative Linguistics in Germany, 1750–1958. Eds. Douglas T. McGetchin, Peter K.J. Park, and Damodar SarDesai. Delhi: Manohar, 2004. 245–70. </bib> <bib>Ricoeur, Paul. Freud and Philosophy: An Essay on Interpretation. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1970. </bib> <bib>______. “Hermeneutics and the Critique of Ideology.” Hermeneutics and the Human Sciences. Ed. and trans. John B. Thompson. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993. 63– 100. </bib> <bib>Said, Edward. Orientalism. New York: Vintage Books, 1979. </bib> <bib>Schlegel, August Wilhelm von, trans. Bhagavad-Gītā, id est Thespesion Melos sive Almi Krishnae et Arjunae Colloquium de Rebus Divinis, Bharatae Episodium. Bonn: Edward Weber, 1823. </bib> <bib>Schlegel, Friedrich. “Gespräch über Poesie.” Kritische Friedrich-Schlegel-Ausgabe. Vol. 2. Ed. Ernst Behler. Paderborn: Schöningh, 1967. 284–98. </bib> <bib>_____. Über die Sprache und Weisheit der Indier. Kritische Friedrich-Schlegel-Ausgabe. Vol. 8. Eds. Ernst Behler and Ursula Struc-Oppenberg. Paderborn: Schöningh, 1975. 105–433. </bib> <bib>_____. “On the Language and Wisdom of the Indians.” The Aesthetic and Miscellaneous Works of Frederick von Schlegel. Trans. E.J. Millington. London: Henry G. Bohn, 1849. 425– 526.</bib> <bib>Weigle, G.H. Preface to “Essay on the Episode of the Mahabharat, Known by the Name of Bhagvat-Geeta; by Baron William de Humboldt.” The Bhagvat-Geeta, Dialogues of Krishna and Arjoon; in Eighteen Lectures. Ed. J. Garrett. Bangalore: The Wesleyan Mission Press, 1849. 121. </bib> <bib>Wilkins, Charles, trans. The Bhagvat-Geeta. 1785. Reprint, Delmar, N.Y.: Scholars’ Facsimiles & Reprints, 1972. </bib> <bib>Williamson, George S. The Longing for Myth in Germany: Religion and Aesthetic Culture from Romanticism to Nietzsche. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004. </bib> <bib>Willson, A. Leslie. A Mythical Image: The Ideal of India in German Romanticism. Durham: Duke University Press, 1964.</bib> <bmh>Notes</> <en>1 Ricoeur’s 1973 distinction can perhaps be traced back to its more famous precedent in Freud and Philosophy: An Essay on Interpretation (1970). There Ricoeur described the “hermeneutics of recollection” versus the “hermeneutics of suspicion” (28–36). 2 See The German Gītā: Hermeneutics and Discipline in the German Reception of Indian Thought, 1778–1831. 3 Indeed, the last few years have seen the appearance of a remarkable body of scholarship that uncovers the historical complexity of German Orientalism, raising important questions about the applicability of both Gadamerian and Saidian approaches. See, for example, Todd Kontje, German Orientalisms; Douglas McGetchin, Peter K.J. Park, and Damodar SarDesai, eds., Sanskrit and ‘Orientalism’: Indology and Comparative Linguistics in Germany, 1750–1958; Tuska Benes, In Babel’s Shadow: Language, Philology, and the Nation in Nineteenth-Century Germany; Jörg Esleben, Christina Kraenzle, and Sukanya Kularni, eds., Mapping Channels between Ganges and Rhein: German-Indian Cross-Cultural Relations; Nicholas Germana, The Orient of Europe: The Mythical Image of India and Competing Images of German National Identity; and Suzanne L. Marchand, German Orientalism in the Age of Empire: Religion, Race, and Scholarship. 4 “Ueber die under dem Namen Bhagavad-Gîtâ bekannte Episode des Mahâ-Bhârata [I and II].” 5 For a full account of Humboldt’s reading of the Bhagavadgītā, see my essay, “The Problem of Action in the Early German Interpretation of the Bhagavadgītā” in Mapping Channels between the Ganges and the Rhein. 6 The “Pantheism Controversy” broke out in 1783 when philosopher Friedrich Heinrich Jacobi revealed a supposed death-bed confession by Lessing: he (Lessing) had secretly been a long-time devotee of Spinoza’s philosophy. This caused a scandal. Lessing was a standard-bearer of the Enlightenment, and if he had taken his guidance from Spinoza, something vital (and dangerous) was revealed about the Enlightenment: it was essentially pantheistic. In late eighteenth century intellectual life, that necessarily meant that the Enlightenment project was also atheistic and morally bankrupt. 7 The call for the “new mythology” inspired by India appears in Ludoviko’s famous exhortation in Gespräch über die Poesie (1800). 8 “All other Oriental doctrines, however disguised by error and fiction, are found in, and dependent on, divine and marvelous revelations; but Pantheism is the offspring of unassisted reason [“ist das System der reinen Vernunft”: “is the system of pure reason”], and therefore marks the transmission [Übergang] from the Oriental to the European philosophy” (F. Schlegel, “On the Language and Wisdom of the Indians” 490, with my interpolations; original available in the Kritische Ausgabe 8: 243). 9 “[C]riticam et grammaticam Bhagavad-Gîtae rationem ... satis expedisse mihi videor; philosophicam nondum attigi” (A.W. Schlegel xxiv) [it seems appropriate to me to have worked out the critical and grammatical basis of the Gītā; the philosophical I have not yet touched upon] (my translation). 10 For an extensive treatment of these impulses in Schlegel’s translation, see The German Gītā 183–97. See also my essay “Epilinguistic Hypophecy” in Epilanguages: Beyond Idioms and Languages. 11 For another nuanced version of this theoretical balancing act, see the introduction to Dorothy M. Figueira’s The Exotic: A Decadent Quest. 12 See Bruce Lincoln, Theorizing Myth: Narrative, Ideology, and Scholarship; Dorothy M. Figueira, Aryans, Jews, Brahmins: Theorizing Authority through Myths of Identity; and A. Leslie Willson, A Mythical Image: The Ideal of India in German Romanticism. 13 The “micro-physics” of practice is a concept that guides Foucault’s analysis in Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. See 29–30.