Chapter Fourteen - Emporia State University

advertisement

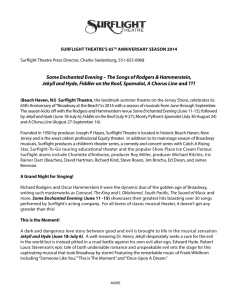

NEW DIRECTIONS (1970-1979) KENRICK, CHAPTER 14 “VARY MY DAY” THE ROCK MUSICAL HAIR inspired several new rock musicals. TWO GENTLEMEN OF VERONA (1971) was a rock, multiracial adaptation of Shakespeare’s comedy that first played in Central Park and then ran for almost 2 years on Broadway. DUDE (1972) reunited Rado and Ragni from HAIR (16 performances) VIA GALACTICA (1972) lasted only 7 performances and replaced the stage of the Broadway Theatre with a giant trampoline Between them, DUDE and VIA GALACTICA lost $1.8 million. Thurio’s Samba from the London Production (1973) THE ME NOBODY KNOWS (1970) A revue-like collage of songs based on poems by inner city children. Performed by a youthful cast of unknowns, it became a celebration of the human spirit triumphing over misfortune. A rave review in the Times sparked audience interest, and word of mouth did the rest. After seven months OffBroadway, the production moved to the Helen Hayes and ran profitably for 20 more. GODSPELL (1971) Greg Evigan, Don Scardino & Paul Shaffer from original Toronto production in 1972. American critics were kind to composerlyricist Stephen Schwartz's take on the new testament (2,651), which started offBroadway on a meager budget and became a phenomenal success. The upbeat score included "Day By Day," "Turn Back, O Man" and "Prepare Ye the Way of the Lord.” Multiple casts played throughout North America. Link to 2012 revival. ORIGINAL TORONTO CAST (1971) Victor Garber Eugene Levy Martin Short Gilda Radner Andrea Martin The music director was Paul Shaffer DAVE THOMAS WITH EUGENE LEVY AS JESUS ORIGINAL CHICAGO CAST WITH JOE MANTEGNA Joe Mantegna (with beard) and Karla DeVito are in the second row from the bottom. JESUS CHRIST SUPERSTAR (1971) Broadway's first full-fledged rock opera came from two British newcomers, composer Andrew Lloyd Webber and librettist Tim Rice. Jesus Christ Superstar (720) began life as a best-selling studio recording. The intriguing premise was to examine the role popular fame played in Christ's fate. JCS was a world away from the rock musicals of the late 1960s. With all dialogue set to music, this work qualified as the first rock opera. Broadway audiences didn't much mind the highpowered staging by Hair alumni Tom O'Horgan, but a more effective London production ran for a record-setting 3,358 performances. With this hit, Webber and Rice initiated a new creative era for the British musical theatre. GREASE (1972) Grease (3,388) won America's heart with a 1950s rock n' roll score and a hokey story about white trash high school kids finding friendship and romance during their senior year. It had enough low comedy, coarse language and general goodwill to entertain millions. After opening on the Lower East Side, the show soon moved to Broadway and became the most commercially successful 1970s rock musical. Grease set a new record as Broadway's longest running musical – a distinction it would hold until A Chorus Line surpassed it in the 1980s. The 1978 big screen version became the highest-grossing screen musical up to that time, and a 1994 Broadway revival supervised by Tommy Tune ran for 1,503 performances. BLACK MUSICALS WITH ROCK SCORES Purlie (1970) Raisin (1973) The Wiz (1975) ROCK OPERA FAILURES THE LIEUTENANT (1975) was a rock opera about the My Lai massacre. ROCKABYE HAMLET (1976) was based on Shakespeare's classic drama. Gower Champion staged the show like an all-out rock concert, and the result was such an incoherent mess that many found it hard to believe that Champion could have been responsible for it. The score included "He Got It in The Ear," and disgruntled audiences laughed when the despairing Ophelia strangled herself with a microphone cord. Bad rock and bad theatre, it closed in just one week. THE ROCKY HORROR SHOW (1973, 1975) THE ROCKY HORROR SHOW was the creation of a London musician, artist, composer, actor named Richard O’Brien. After a brief run in a London night club, it played at the Roxy in Los Angeles, where they made the cult film prior to its Broadway debut in 1975 (45 performances). A 2000 Broadway revival played 437 performances. THE CONCEPT MUSICAL In One More Kiss: The Broadway Musical in the 1970s (New York: Palgrave, 2003), Ethan Mordden defines a concept musical as "a presentational rather than strictly narrative work that employs out-of-story elements to comment upon and at times take part in the action, utilizing avant-garde techniques to defy unities of time, place and action." Once a subject or situation is raised (marriage, love, finding a job, etc.) characters can comment on or illustrate aspects of the subject. There is a solid storyline, but all the major elements of these shows are linked in some way to the central concept. Harold Prince was not thrilled that so many of his shows are referred to as concept musicals – "The whole label that was put on our shows, the whole notion of the 'concept' musical, was one that I really resent. I never wished it on myself. It caused a backlash and animosity towards the shows and us . . . It's called a 'unified' show, an 'integrated' show." Craig Zadan's Sondheim & Co., Harper and Row, New York, 2nd edition, 1986, p. 362) By any name, the musicals that Prince, Sondheim and their various collaborators offered in the early 1970s re-energized the Broadway musical, setting the genre on a soulsearching course that redefined the genre. Historian Foster Hirsch explains how Prince and Sondheim, though different, complemented each other – Prince galloping ahead while Sondheim holds tightly onto the reins; Prince the affable public relations man, glibly articulating concepts and trajectories, Sondheim leery of publicity; Prince relishing the activity of the rehearsal process, Sondheim disliking it: out of the fusion of their temperamental dissimilarities they have become modernism's answer to Rodgers and Hammerstein – the makers of the self-reflexive musical. Harold Prince and The American Musical Theater (New York: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1989, p. 71) PRINCE AND SONDHEIM Five years after his bitter experience working as lyricist on Do I Hear A Waltz (1965 - 220), Stephen Sondheim returned to Broadway as a fulltime composer/lyricist. He formed a creative partnership with producer/director Harold Prince, and the duo saw their innovative concept musicals become the most acclaimed hits of the early 1970s. They worked with a series of librettists on shows built around a "concept”. Through this central issue or idea, each show examined numerous characters and relationships. Sondheim and Prince were assisted in their first two efforts by choreographer Michael Bennett, who would independently create the most successful concept musical of all. COMPANY (1970) George Furth's libretto for Company (706) used Bobby, a single 30something man seeking love in contemporary Manhattan, to focus on the problems and gentle insanities of five couples – Bobby's "good and crazy" married friends – as well as the various single women vying for Bobby's hand. As Bobby confronts the emotional confusion brought on by his thirty-fifth birthday, he realizes that a myriad of friends are no replacement for sharing intimate love with one person. Bennett's choreography embodied everything from a surprise party to coitus, and Prince's direction kept this bountiful mix in sharp focus. Dean Jones headed Company's original cast but left early in the run. He was replaced by Larry Kert. Sondheim's score was pure Broadway with a contemporary edge. Much of that edge came from inventive, literate, dramatically potent lyrics. For example, the often-married character Joanne (played by Elaine Stritch) observed that perfect marital relationships are made by the "tactics you employ, neighbors you annoy" and "children you destroy . . . together." Sondheim's marriage of wit and heart was a vibrant continuation of what Berlin, Porter, Ira Gershwin and Oscar Hammerstein II (Sondheim's mentor) had done in earlier eras. But Sondheim's lyrics spoke for a generation in the midst of a cultural and sexual revolution. As no one else before or since, he gave uncertainty and self-exploration an eloquent, intriguing voice. Neil Patrick Harris – Being Alive Raul Esparza – Being Alive 2011 revival “Side by Side by Side” Dean Jones – Being Alive 1996 London – Not Getting Married Glee 2013 – Not Getting Married Lea Salogna – Another Hundred People FOLLIES (1971) In Follies (522), the libretto by playwright James Goldman centered on two former showgirls and their spouses assessing embittered marriages while attending a reunion of performers from a Ziegfeld era Broadway revue. Sondheim's wide-ranging score evoked various musical styles of the past. While the melodies had a traditional sound, the lyrics often went for the jugular, ("Could I leave you? Yes! Will I leave you? Guess!"). No musical had ever taken such a frank look at the painful realities of growing older and abandoning one's dreams. Bennett's innovative choreography was a crucial element, showing characters in a parallel past and present. Follies was not a commercial success, but its magnificent score made it a favorite with theatre buffs. Bernadette Peters sings “Losing my Mind in the 2011 revival. A LITTLE NIGHT A Little Night Music (600), Sondheim MUSIC (1973) For and librettist Hugh Wheeler had a central love story, but like its inspirational source (Ingmar Bergman's film Smiles of A Summer Night) that romance became an excuse to focus on numerous characters and relationships. As an aging actress (Glynis Johns) tried to re-ignite a past amour with a married attorney (Len Cariou), love was examined from the perspectives of youth, middle age and seniority, creating a haunting, bittersweet collage. Sondheim composed the entire score in variations of waltz time, so even the music was built around a concept. The show's most popular number, "Send In The Clowns," would be the only time a song with words and music by Sondheim became a best-selling pop chart hit. PACIFIC OVERTURES (1976) In Pacific Overtures (193) the book by John Weidman examined how Japan's ancient culture was wrenched when the American Navy forced the isolated island nation to open to international trade in 1853. The story is told from a Japanese point of view as broad array of characters take the story through the decades, with a finale set in contemporary times (skipping any mention of World War II). The score was one of Sondheim's most intriguing, including musical haiku and pastiches of Sullivan and Offenbach. Highlights included the extended musical scenes "Chrysanthemum Tea," "Please Hello" and "Someone In A Tree" – each a well crafted mini-musical that brought a separate set of characters to life. Prince adapted ancient kabuki techniques for the staging, using a mostly male Asian cast. Pacific Overtures was so innovative that American audiences did not know what to make of it. An exquisite Off-Broadway revival won critical acclaim in 1984, but did not see a much longer run than the original -- and subsequent revivals have reached a small but dedicated audience. Perhaps this unique musical is too challenging to win mass approval. PIPPIN (1972) Bob Fosse reached his creative peak in the 1970s. While turning out acclaimed films and TV specials, he offered Broadway three dance-centered concept musicals, where a central concept drove the show, rather than a traditional plot. Fosse's directorial vision took total precedence over the book or score – Pippin (1,944) used the story of Charlemagne's forgotten son as a flimsy excuse to examine jealousy, sex, war, sex, love, sex, life, sex . . . and sex. When composer Stephen Schwartz disagreed with changes made to his score, Fosse barred him from rehearsals. Thanks to Fosse's erotically charged choreography and teasing TV ad, Pippin ran long and toured far. John Rubenstein charmed audiences in the title role. BOB FOSSE HAD A CAREER YEAR IN 1973 His film of CABARET earned him an Academy Award. His TV special LIZA WITH A Z earned him an Emmy Award. His direction of PIPPIN earned him a Tony Award. CHICAGO (1975) Fosse's stylish and sexy choreography was also evident in Chicago (898), the saga of two 1920s flappers seeking fame through marital homicide. This concept musical cast a cynical, merciless spotlight on social hypocrisy and mediabased celebrity. Fosse helped shape the libretto, staged the scenes as a series of vaudeville-style acts. Gwen Verdon (in her final musical role) and Chita Rivera were the stellar killers, and Jerry Orbach played their "razzle dazzle" attorney. The John Kander and Fred Ebb score offered a parade of showstoppers, including "All That Jazz." One of the most brilliant and biting musicals Broadway would ever produce, Chicago was overshadowed by the success of A Chorus Line and did not win a single Tony. It took a 1996 Broadway revival and a 2002 film version to bring it the popularity it deserved. DANCIN’ (1978) With Dancin' (1,744), Fosse took concept shows a step further and dispensed with a script and original score, building an entire evening of unrelated dance sequences around nothing more than a gifted cast, a title and pre-existing, nontheatrical musical sources like Benny Goodman's jazz classic "Sing, Sing, Sing." Alan Jay Lerner wired Fosse, "Congratulations. You finally did it. You got rid of the author, " but the public and critics adored the results, making this one of Fosse's most profitable productionsAlthough Fosse never had another original stage hit after Dancin', his legacy as a choreographer and director would outlive him. In 1999, more than a decade after his death, the Broadway dance revue Fosse (supervised by Gwen Verdon) introduced a new generation to this showman's genius. MICHAEL BENNETT Director, choreographer, dancer (Michael DeFiglia) b. April 8, 1943 (Buffalo, NY) d. July 2, 1987 (Tuscon, Arizona) After dancing in the choruses of several Broadway shows, Bennett made his choreographic debut with A Joyful Noise (1966). He staged dances for Promises, Promises (1968) and director Hal Prince's productions of Stephen Sondheim's innovative hits Company (1970) and Follies (1971). At a series of private sessions in the early 1970s, Bennett tape recorded the memories and musings of veteran Broadway dancers. This material formed the basis for A Chorus Line (1975), which Bennett directed and choreographed. The show became a sensation, receiving several Tonys and the Pulitzer Prize, and going on to a record-setting Broadway run. Bennett's innovative Ballroom (1978) displeased critics and closed in a matter of weeks, but his stylish Dreamgirls (1981) became a long-running hit. After his marriage to Donna McKechnie ended in divorce, he abandoned the musical Scandal in mid-workshop, and was forced to give up directing the longawaited Chess when he was diagnosed with AIDS. SEESAW (1973) Seesaw is a musical with a book by Michael Bennett, music by Cy Coleman, and lyrics by Dorothy Fields. directed and choreographed by Bennett, opened on March 18, 1973 at the Uris Theatre. It later transferred to the Mark Hellinger; between the two venues, it ran a total of 296 performances. The opening night cast included Ken Howard, Michele Lee, Tommy Tune, Giancarlo Esposito, Thommie Walsh, Amanda McBroom and Baayork Lee. Reviews were universally good, but there was no money for newspaper ads to quote them or thirty-second television spots to promote the show. As a publicity stunt, New York City Mayor John V. Lindsay was persuaded to appear on stage during a production number set in Times Square, and the ensuing media coverage resulted in a boost at the box office. Tommie Tune was featured in the touring production. A CHORUS LINE (1975) The concept musical reached its peak with A Chorus Line (6,137), the brainchild of Michael Bennett. He had Broadway chorus dancers (known in the business as "gypsies" because they go from show to show) share memories while a tape recorder ran. Working with these tapes, Bennett built a libretto with writers Nicholas Dante and James Kirkwood. Concurrently, composer Marvin Hamlisch and lyricist Edward Kleban developed a vibrant score. The concept was a Broadway chorus audition where a director demands that his dancers share their most private memories and inner demons. Some dismissed this as staged group therapy, but most found that the result was riveting theatre. A Chorus Line glorified the individual fulfillment that can be found in ensemble efforts. When the entire cast sang of being "One" while dancing and singing in rigid roup formation, the effect was dazzling. Veteran chorus dancers Donna McKechnie, Kelly Bishop and Sammy Williams won Tonys, as did the entire creative team. A Chorus Line's popularity crossed all lines of age and musical taste, smashing every other long-run record in Broadway history. Many who came of age during its run dubbed it the best musical ever. REVIVALS NO, NO NANETTE (1971) ran 861 performances LORELEI (1974) was a revised Gentlemen Prefer Blondes with Carol Channing GYPSY (1974) with Angela Lansbury as Mama Rose MY FAIR LADY (1976) ran for a year with George Rose as Alfred Doolittle AN ALL-BLACK GUYS AND DOLLS (1976) REVIVALS HELLO, DOLLY! (1975) with Pearl Bailey (1978) with Carol Channing FIDDLER ON THE ROOF (1976) with Zero Mostel MAN OF LA MANCHA (1970, 1977) Sandy Duncan in PETER PAN (1979) REVIVALS OKLAHOMA! (1979) VERY GOOD EDDIE (1975) THE KING AND I (1977) ran in the Uris with Yul Brynner for 2 years. He died a few months after his final performance. CANDIDE (1974) Hal Prince restaged Leonard Bernstein's unsuccessful 1956 operetta Candide (740) as a wacky Off-Broadway farce, underplaying the grander aspects of the score and stressing physical comedy. This rollicking production delighted the critics, moved to the Broadway Theater and ran for two profitable years. RICHARD RODGERS TWO BY TWO (with Martin Charnin) starring Danny Kaye (1970) REX (1976) with Sheldon Harnick starring Nicol Williamson I REMEMBER MAMA (1979) with Liv Ullman He died December 30, 1979 LERNER AND LOEWE GIGI (1973) Alan Jay Lerner and Frederick Loewe adapted their 1958 screen classic Gigi (110) for Broadway. Despite the stellar presence of Alfred Drake, Maria Karnilova and Agnes Moorhead, the production lost a fortune. JERRY HERMAN MACK AND MABEL (1974) ran for only 69 performances. The show featured one of Jerry Herman's finest scores and a cast headed by Robert Preston and Bernadette Peters. But the tragic true life love story of silent screen director Mack Sennett and actress Mabel Normand made the libretto unworkable. APPLAUSE (1970) The book musical had been a Broadway's staple since Oklahoma, and the format managed an impressive comeback in the 1970s. Several writers took the common sense approach of adding contemporary musical flavoring to otherwise conventional musicals. Charles Strouse and Lee Adams, who used early rock and roll effectively in Bye Bye Birdie, had similar success with Applause (900), which re-set the backstabbing plot of the film All About Eve in the theatrical world of 1970. This time, rock rhythms and orchestrations gave a "mod" sound to traditional showtunes, and the presence of 1940s movie star Lauren Bacall cemented the show's success with mainstream theatregoers. She couldn't sing worth a damn, but her star power sold plenty of tickets. ANNIE (1976) Some suggested that the standard book musical was an endangered Broadway species. Then an orphan girl and a scruffy dog re-energized the genre. Both critics and audiences melted for Annie (2,377), a shamelessly old-fashioned musical inspired by the comic strip Little Orphan Annie. It told how a penniless tyke met and captured the heart of billionaire Daddy Warbucks, finding love, adventure and a loveable mutt named Sandy along the way. Newcomer Andrea McArdle gave a disarming performance in the title role, and Dorothy Loudon copped the Tony with a hilarious performance as Miss Hannigan, the harried orphanage director who has come to loathe "Little Girls." The 2012 revival official site. OTHER SUCCESSES SHENANDOAH (1975) Based upon a civil war era play, it featured John Cullum as the play’s patriarch. THE BEST LITTLE WHOREHOUSE IN TEXAS (1978) A musical about Texas, politics, football and sex. Directed by Tommy Tune. Despite decent runs, both Purlie and Raisin wound up losing money. At the other extreme, AIN’T MISBEHAVIN’ (1978 - 1,604) revitalized the revue format with an all-black cast in beguiling vignettes built around the songs of Fats Waller. OTHER SUCCESSES THEY’RE PLAYING OUR SONG (1979) featured music by Marvin Hamlisch and a book by Neil Simon SUGAR BABIES (1979) with Mickey Rooney and Ann Miller in a revue-style Burlesque show A CHANGING CLIMATE It's not so much that the public disapproved of these well-written but imperfect shows. Most Americans were not paying attention to the musical theatre anymore, and consequently musicals had become a sort of subculture. Rock and disco were the predominant sounds in popular music, and neither genre had more than a token presence in most Broadway scores. The potential sales for cast albums had fallen so low that major labels stopped recording them altogether. To make matters worse, by 1979, most Broadway musicals cost $1,000,000 or more to produce, and weekly operating expenses were so high that even a two year run could not guarantee a profit. Some blamed the volatile economy, but Broadway was the only place where inflation (a widespread problem in the 1970s economy) had run at a rate of 400 percent. In this unsettled environment, two important musicals came to represent the forces that would compete for the soul of musical theatre in the decade to come. SONDHEIM VS. LLOYD WEBBER SWEENEY TODD (1979) While Stephen Sondheim's Sweeney Todd (557) used a conventional plot structure, its operatic score was Sondheim's most ambitious effort to date. Going further, this blood-soaked tale of an unjustly persecuted man's all-consuming quest for revenge in Victorian London explored emotional territory no musical had ever touched before. SONDHEIM VS. LLOYD WEBBER Not since Shakespeare had a poet of the theatre taken such an unflinching look into the darkest corners of the human soul. When Sweeney's cast pointed at audience members and insisted that they had a murderous hate like Sweeney's hiding inside them, it was bound to leave many theatergoers uneasy. Tony-winning performances by Angela Lansbury and Len Cariou added to the impact, as did a massive production helmed by Hal Prince. (Prince framed the action in the actual ruins of an old factory, trucked in from Rhode Island.) But this lofty accomplishment came at a crippling price. Despite a healthy run and numerous awards, the show was unable to turn a profit. A far different musical came from England with advance hoopla that Gilbert and Sullivan might have envied. Following the pattern they had initiated with Jesus Christ Superstar, Andrew Lloyd Webber and librettist Tim Rice launched their stage biography of Argentina's Eva Peron as a recording. Working with director Hal Prince, they refined it on stage in London, sharpening the book's focus, toning down the rock elements and adding a touch of disco to expand the score's commercial possibilities. SONDHEIM VS. LLOYD WEBBER By the time it reached Broadway, Evita (1979 1,567) was a slick and stylish smash hit, with breakthrough performances by Patti Lupone as Evita and Mandy Patinkin as Che. A disco version of "Don't Cry For Me Argentina" became a hit. Evita was a calculated triumph of stagecraft and technology, undeniably entertaining but in some ways as vapid as any of Ziegfeld's Follies. Webber and Rice depicted Eva as a whore with flair and ruthless ambition, but gave no clue as to what made her complex character tick. Meaningful or not, people liked it. Running three times longer than Sweeney Todd, it made a massive profit from productions all over the world. With this flashy victory of matter over mind, the Mega-musical was born. Link to montage from 2012 revival. Samantha Barks sings “Another Suitcase in Another Hall (2013) THE MEGAMUSICAL Both Sweeney and Evita were expensive productions with stunning stage direction by Hal Prince, and both won seven Tony Awards (including Best Musical) in adjoining seasons. The key difference: Sweeney Todd lost money, Evita made money. This was not lost on producers and investors. It is easy for armchair critics to advocate artistic merit over financial concerns, but answer this: If you were investing $100,000 or more of your own money, would you prefer to lose it or make a profit? The inevitable answer to that question set the uneasy course of the Broadway musical for the remainder of the 20th Century. SOURCES Kenrick, John MUSICAL THEATRE A HISTORY (New York: Continuum, 2008) Kenrick, John Musicals 101 <http://www.musicals101.com/>