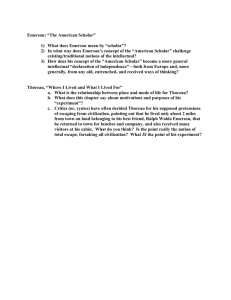

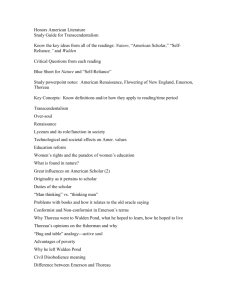

Week 3, Day 1, Emerson

advertisement

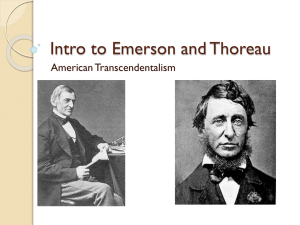

Early American Environmental Texts: Rowlandson, Crevecoeur, Emerson Letters from an American Farmer J. Hector St. John De Crevecoeur (1782) Key terms/ideas: pastoral, georgic, literary agrarianism, wilderness Crevecoeur Michel Guillaume Jean de Crèvecœur (December 31, 1735 – November 12, 1813). Naturalized in New York as John Hector St. John in 1759. French-American writer. In 1755 he immigrated to New France (Canada, Hudson Bay, Louisiana) in North America, where he served in the French and Indian War as a surveyor in the French Colonial Militia Crevecoeur Spent 1759-1769 traveling colonies. 1769: bought land in Orange County, NY, married, and settled into life as an American farmer. In 1782, in London, he published a volume of narrative essays entitled the Letters from an American Farmer. The book quickly became a literary success, especially in Europe, and turned Crèvecœur into a celebrated figure. Letters Who is the person or narrator whose “voice” we are “hearing” as we read? What kind of character is he? What is the voice like? Letters Form: epistolary Genre: literary agrarianism, philosophical travel narrative Guiding question: how is a European or a new immigrant to see America? (see page 1) This is American literature, but it is still an America as dreamed of by the European mind. Crevecoeur: Letters An European, when he first arrives, seems limited in his intentions, as well as in his views; but he very suddenly alters his scale; two hundred miles formerly appeared a very great distance, it is now but a trifle; he no sooner breathes our air than he forms schemes, and embarks in designs he never would have thought of in his own country. There the plenitude of society confines many useful ideas, and often extinguishes the most laudable schemes which here ripen into maturity. Thus Europeans become Americans. (10) Letters 1 What kinds of landscape or environment are of interest in this text (Letter III)? 2 What are the text’s attitudes towards these landscapes? Crevecoeur: Letters He must greatly rejoice that he lived at a time to see this fair country discovered and settled; he must necessarily feel a share of national pride, when he views the chain of settlements which embellishes these extended shores. When he says to himself, this is the work of my countrymen, who, when convulsed by factions, afflicted by a variety of miseries and wants, restless and impatient, took refuge here. They brought along with them their national genius, to which they principally owe what liberty they enjoy, and what substance they possess. Here he sees the industry of his native country displayed in a new manner, and traces in their works the embryos of all the arts, sciences, and ingenuity which flourish in Europe. Here he beholds fair cities, substantial villages, extensive fields, an immense country filled with decent houses, where an hundred years ago all was wild, woody, and uncultivated! What a train of pleasing ideas this fair spectacle must suggest; it is a prospect which must inspire a good citizen with the most heartfelt pleasure. (1) Crevecoeur: Letters The rich and the poor are not so far removed from each other as they are in Europe. Some few towns excepted, we are all tillers of the earth, from Nova Scotia to West Florida. We are a people of cultivators, scattered over an immense territory communicating with each other by means of good roads and navigable rivers, united by the silken bands of mild government, all respecting the laws, without dreading their power, because they are equitable. (1) “Cultivators of the earth are the most valuable citizens. They are the most vigorous, the most independent, the most virtuous, & they are tied to their country & wedded to its liberty & interests by the most lasting bonds.” - Thomas Jefferson Pastoral vs. Georgic Pastoral (in its simplest and least radical form)—an idealized alternative space in which nostalgic fantasy or national allegory can unfold. Georgic—a more pragmatic, rather than meditative, account of the land (and specifically of agricultural work on the land). Letters “Letter III” frames American character as a function of how Americans relate to and dwell in their environment. (see pages 1, 3) “Letter III” draws on the myth of America as new beginning (and return to Eden). (see pages 2, 10) Cultivate. Cultivate! Cultivate!! Crevecoeur: Letters In offering a certain conception of progress, of how cultivation happens, Crevecoeur differentiates between first settlers and later settlers: See pages 4, 5, 7, 9 Thus are our first steps trod, thus are our first trees felled, in general, by the most vicious of our people; and thus the path is opened for the arrival of a second and better class, the true American freeholders; the most respectable set of people in this part of the world: respectable for their industry, their happy independence, the great share of freedom they possess, the good regulation of their families, and for extending the trade and the dominion of our mother country. (9) Crevecoeur: Letters He does not find, as in Europe, a crowded society, where every place is over-stocked; he does not feel that perpetual collision of parties, that difficulty of beginning, that contention which oversets so many. There is room for every body in America; has he any particular talent, or industry? he exerts it in order to procure a livelihood, and it succeeds. Is he a merchant? the avenues of trade are infinite; is he eminent in any respect? he will be employed and respected. Does he love a country life ? pleasant farms present them-selves; he may purchase what he wants, and thereby become an American farmer. Is he a laborer, sober and industrious? he need not go many miles, nor receive many informations before he will be hired, well fed at the table of his employer, and paid four or five times more than he can get in Europe. Does he want uncultivated lands? Thousands of acres present themselves, which he may purchase cheap. Whatever be his talents or inclinations, if they are moderate, he may satisfy them. (10) Crevecoeur: Letters To examine how the world is gradually settled, how the howling swamp is converted into a pleasing meadow, the rough ridge into a fine field; and to hear the cheerful whistling, the rural song, where there was no sound heard before, save the yell of the savage, the screech of the owl, or the hissing of the snake? (14) Crevecoeur: Letters "Welcome to my shores, distressed European; bless the hour in which thou didst see my verdant fields, my fair navigable rivers, and my green mountains! If thou wilt work, I have bread for thee; if thou wilt be honest, sober, and industrious, I have greater rewards to confer on thee-- ease and independence. I will give thee fields to feed and clothe thee; a comfortable fireside to sit by, and tell thy children by what means thou hast prospered; and a decent bed to repose on. I shall endow thee beside with the immunities of a freeman. If thou wilt carefully educate thy children, teach them gratitude to God, and reverence to that government that philanthropic government, which has collected here so many men and made them happy. I will also provide for thy progeny; and to every good man this ought to be the most holy, the most Powerful, the most earnest wish he can possibly form, as well as the most consolatory prospect when he dies. Go thou and work and till; thou shalt prosper, provided thou be just, grateful and industrious.” (15) Intro to Emerson and Thoreau American Transcendentalism Transcendentalism (1836-1844) Emerson’s “Nature” is published in 1836 – taken as the manifesto of the Transcendental Club. This is the same year (1836) that the club forms, with Emerson as one of its founding members. The Transcendental Club begins to publish the Dial, a magazine (1840-1844). Transcendentalism: Central Ideas Union of spiritual and physical realities: immersion in nature can lead to spiritual insight. Divinity in nature – transcendental natural reality. We don’t normally have access to this reality, but can glimpse it in moments. The mind is creative in perception, not just a passive receptor of impressions. Reason (a high, intuitive form of perception) vs. Understanding (working through logical premises) – a distinction adapted from Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Human beings are products of nature – perfect end result. Ralph Waldo Emerson One of the most important writers of mid-19th century America. Poet; speaker; journal/essay writer. Unitarian minister who moves away from Christianity towards pantheistic language. Resigns pastorate and becomes a lecturer. Religious, but does not want to be restrained by dogma. Nature Central question: why does nature exist? What is it’s relationship to ME, if it is NOT ME? Emerson wants an “original relation to the universe” (27). Insight v. tradition Revelation v. history Believes answers to all questions are possible to discover. Science – all about finding a theory of nature. Know reality through studying nature. Art = “mixture of his [man’s] will” with nature (28) Idea of correspondences: inner and outer, part and whole, mind/spirit and world Anthropocentric/Ecocentric Not a binary, but a continuum. Where does a given text (or philosophy) place its value? Manifestation in language? Stylistic or formal features of the text. Emerson: ecocentric/anthropocentric? “Nature, in its ministry to man, is not only the material, but is also the process and the result. All the parts incessantly work into each other’s hands for the profit of man.” (31) “Nature is thoroughly mediate. It is made to serve. It receives the dominion of man as meekly as the ass on which the Saviour rode. It offers all its kingdoms to man as the raw material which he may mould into what is useful … One after another his victorious thought comes up with and reduces all things, until the world becomes at last only a realized will,--the double of the man.” (from the chapter “Discipline”) The Poet’s Perception When we speak of nature in this manner, we have a distinct but most poetical sense in the mind. We mean the integrity of impression made by manifold natural objects. It is this which distinguishes the stick of timber of the wood-cutter, from the tree of the poet. The charming landscape which I saw this morning, is indubitably made up of some twenty or thirty farms. Miller owns this field, Locke that, and Manning the woodland beyond. But none of them owns the landscape. There is a property in the horizon which no man has but he whose eye can integrate all the parts, that is, the poet. This is the best part of these men's farms, yet to this their warranty-deeds give no title. Nature Love of nature has eye/heart of child “wild delight” (29) Famous passage: transparent eyeball, “glad to the brink of fear” Transparent eye-ball passage 1. What is Emerson proposing happens in the woods? (try to paraphrase as much of the passage as you can) 2. What do you notice about the language of this passage? Is Emerson using any poetic devices? (or in other words, think about the style of this passage, how it is written) 3. Based on your reading of the passage, come up with ONE detailed question to ask about the passage and about the essay more generally. “Standing on the bare ground, -- my head bathed by the blithe air, and uplifted into infinite space, -- all mean egotism vanishes. I become a transparent eye-ball; I am nothing; I see all; the currents of the Universal Being circulate through me; I am part or particle of God.” Nature—A radical new imagination of woods and wilderness: Correspondences The greatest delight which the fields and woods minister, is the suggestion of an occult relation between man and the vegetable. I am not alone and unacknowledged. They nod to me, and I to them. The waving of the boughs in the storm, is new to me and old. It takes me by surprise, and yet is not unknown. Its effect is like that of a higher thought or a better emotion coming over me, when I deemed I was thinking justly or doing right. (28) Nature—A radical new imagination of woods and wilderness: Correspondences Yet it is certain that the power to produce this delight, does not reside in nature, but in man, or in a harmony of both. It is necessary to use these pleasures with great temperance. For, nature is not always tricked in holiday attire, but the same scene which yesterday breathed perfume and glittered as for the frolic of the nymphs, is overspread with melancholy today. Nature always wears the colors of the spirit. To a man laboring under calamity, the heat of his own fire hath sadness in it. Then, there is a kind of contempt of the landscape felt by him who has just lost by death a dear friend. The sky is less grand as it shuts down over less worth in the population. (29) Nature’s Multiple Uses 1. Commodity – food, air, water, earth – physical uses. Everything humans build comes from nature. 2. Beauty – idea of nature as cosmos. Love for things in and of themselves. a) Perceiving nature causes delight; we love it just for being beautiful. b) Nature also has spiritual beauty. Connection between noble acts and beautiful scenery. c)Nature has intellectual beauty – absolute order; contemplation leads man to great creation. 3. Spirit- nature also reveals spirit, the “ineffable.” Physical nature is compared to the shadow which indicates the sun behind it. Spirit and Nature The world proceeds from the same spirit as the body of man. It is a remoter and inferior incarnation of God, a projection of God in the unconscious. But it differs from the body in one important respect. It is not, like that, now subjected to the human will. Its serene order is inviolable by us. It is, therefore, to us, the present expositor of the divine mind. It is a fixed point whereby we may measure our departure. As we degenerate, the contrast between us and our house is more evident. We are as much strangers in nature, as we are aliens from God. We do not understand the notes of birds. The fox and the deer run away from us; the bear and tiger rend us. We do not know the uses of more than a few plants, as corn and the apple, the potato and the vine. Is not the landscape, every glimpse of which hath a grandeur, a face of him? Yet this may show us what discord is between man and nature, for you cannot freely admire a noble landscape, if laborers are digging in the field hard by. The poet finds something ridiculous in his delight, until he is out of the sight of men. (50) Nature—Correspondences When I behold a rich landscape, it is less to my purpose to recite correctly the order and superposition of the strata, than to know why all thought of multitude is lost in a tranquil sense of unity. I cannot greatly honor minuteness in details, so long as there is no hint to explain the relation between things and thoughts; no ray upon the metaphysics of conchology, of botany, of the arts, to show the relation of forms of flowers, shells, animals, architecture, to the mind, and build science upon ideas. (51) From Emerson to Thoreau… If Emerson is arguably the most important 19th century American literary figure, Thoreau is arguably the most important 19th century American environmental figure. What are the stereotypes we have of Thoreau? Thoreau: Emerson’s “Earthy Opposite”? Heavily influenced by Emerson Split visions of Thoreau: an ecological saint? Or the wannabe who lived in Emerson’s backyard? Walden never claims to be an experiment in wilderness living….so what is it? What is Walden? Based on the journals Thoreau kept during his stay at Walden Pond. Kept a journal from 1837-1861. Spent 2 years in a cabin at Walden Pond that he built himself (1845-1847). Walden is not published until 1854: nine years of writing and revisions! Walden is thus a highly constructed literary piece – not a direct nature essay or a simple journal.