Arabic Calligraphy - The National Museum of Language

advertisement

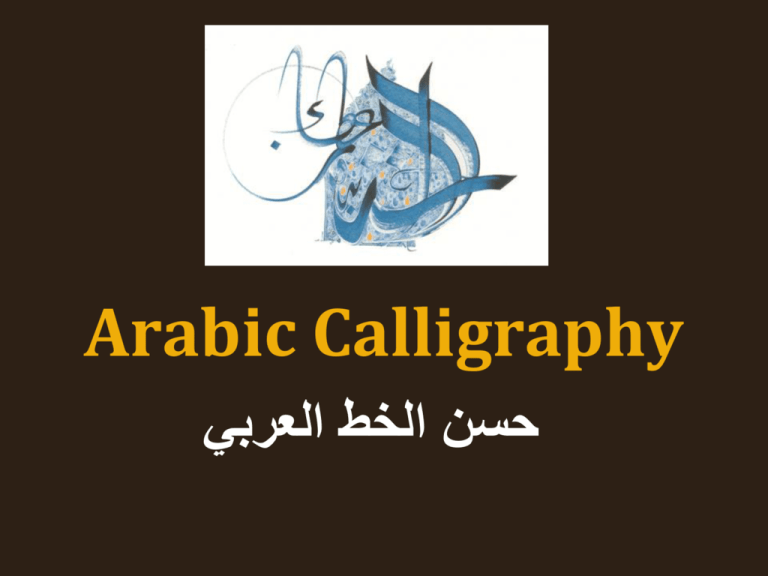

Arabic Calligraphy حسن الخط العربي The Act of Writing • In calligraphy the production of the character is an artistic act. • In calligraphy, each character is treated as a plastic image to convey harmony, grace, and beauty. • Calligraphic styles have changed over time and in relation to different applications. Bismilleh pear calligraphy, wikipedia.org The Act of Writing In calligraphy, each character or word is treated as an image and must satisfy three criteria: Calligraphy courtesy of Hassan Massoudy (Slides one and three) from pagespersoorange.fr/hassan.massoudy 1. Communication (semantic) criteria. It must convey the meaning of the word it represents. 2. Phonetic criteria. It must represent the corresponding sounds of letters it depicts. 3. Aesthetic criteria. A calligraphic work has its own autonomy and integrity as a shape in space. It must meet appropriate artistic standards. Visual Representation • In Arabic and Persian calligraphy characters are sometimes arranged in the forms of plants or animals. This produces a visual message in addition to the linguistic one. • In Arabic calligraphy, characters may be arranged to satisfy mathematical criteria, whose perfect production may itself carry a message. Nastaliq Persian Calligraphy, http://rshamshiri.50megs.com/caligraphy/Persian_Calligraphy.htm Directionality • Most writing is produced in vertical or horizontal lines. • Chinese can be written in three directions: left-to-right, right-to-left, and vertically. • Arabic and Hebrew are written right-to-left, while English and other Latin-based systems are written leftto-right. • Greek writing could be both left-to-right and right-toleft and was sometimes both. • In calligraphy characters may defy the conventions of direction as long as they do not compromise comprehension. • In calligraphy characters are placed in space according to aesthetic or other criteria. Medium Photos of Mauritanian school children with their wood writing tablets (Allouha). Children learn to write and recite the Qu’ran in this way in much of West Africa. (Images from http://www.bourlin gueurs.com/maurit anie/page_09.htm) • The medium selected for writing influences its appearance. • Earliest writing may have been painted on ceramics. • Written texts can be carved in stone, as on grave markers or on buildings, or etched in metal. • They can be woven into fabric, as in carpet making. • Written symbols can also be arranged into slats that form doors or windows. Arabic • Arabic is one of the most important scripts in the world. • It is descended from the early Semitic scripts of western Asia that also lay the basis for Latin and other alphabets. • About 950 million people speak Arabic and many more people use its alphabet. Map of Arabic-speaking countries, wikipedia.org Arabic • Arabic is written from right to left. • Arabic is an efficient language with 17 basic consonants. • Vowels are indicated by markers above, below, or alongside the consonant. • Arabic is generally written in a cursive style with letters linking to one another. • There is no upper and lower case in Arabic letters, but there are rules regarding the form of the letter in relation to it place in the word. Writing and the Word of God Since the words of the Prophet Muhammed may only be written in Arabic, the act of writing has special import in the Islamic world. A calligrapher may be motivated by spiritual inspiration. He may use his calligraphy as a medium to convey the greatness of God. In Islamic traditions, therefore, calligraphy has been held in high regard. Secular calligraphers combine movement of line with poetic meanings to produce aesthetic experience. Arabic Writing: Passing it On! Since the words of the Prophet Muhammed may only be written in Arabic, the Arabic language has traveled far and wide with the spread of Islam. Arabic script is used by languages that are not Semitic, such as Persian, Urdu, Indonesian, and others. These languages have adapted the Arabic alphabet to meet their own phonetic requirements. A Qur’an may have Arabic in the center of the page, and a local translation, also in Arabic script but not language, in the margins. Handwritten letter in Urdu, pakistaniat.com Arabic calligraphy is the art of beautiful writing The Arabic calligrapher uses a reed pen (qalam) with a point cut on an angle. This feature produces a thick down stroke and a thin upstroke with an infinity of gradation in between. Calligraphy writing implements, wikipedia.org Styles • There are many different styles of Arabic Calligraphy. It can be done on many different mediums. • Detailed on the right are a few classic examples of the major styles of Arabic Calligraphy in the Islamic world. Six calligraphic styles, http://www.islamicarchitecture.org Materials • Arabic Calligraphy can be done on many different mediums. • The following slides show classic examples of the major styles of Arabic Calligraphy in the Islamic world. Images: Emirates Air (left) and Arabic graffiti (right) Calligraphy as a Stamp of Authority Tughra (Imperial Cipher) ca. 1555; Ottoman Istanbul. Ink, colors, and gold on paper; 20 1/2 x 25 3/8 in. (52.1 x 64.5 cm) Rogers Fund, 1938 (38.149.1) Metropolitan Museum of Art, www.metmuseum.org. A calligraphic image may represent a stamp of authority. In Ottoman Turkey the tughra was a calligram that served as an emblem of the sultan. Not being easily forged, it was used to legitimize royal decrees, bequests, and coins. It indicated the name of the sultan and his father, as well as the phrase "eternally victorious." A special court artist was required to draw the tughra calligram. An illuminator added delicate natural forms, scroll designs, color, and gold leaf. From the use of the first tughra in 1324, the forms became increasingly ornate and elaborate. The tughra shown to the left, which belonged to the Sultan Suleyman the Magnificent (1520-566), contains three vertical shafts and a number of concentric loops in complex, graceful, flowing lines. In a calligram an inscription takes the form of a flower, bird or other animal, or, with less frequency, an inanimate object such as a ship. Here, the text follows the outline of a peacock's spread tail feathers. Praising an unnamed sultan, it reads: Album leaf, 17th century; Ottoman Turkey Ink, colors, and gold on paper; 9 5/8 x 7 in. Louis V. Bell Fund, 1967 (67.266.7.8r). Metropolitan Museum of Art. “Beautiful …of angelic character, of auspicious omen, envy of the perfect ones, parrot of sweet tongue and sweet speech, peacock of the garden of … the lofty decree, sultan of the sultans of the world, fortunate and august, khaqan of the shahs, Darius of the time, Faridun of the age, hero of the world, [text reverses direction] champion of earth and time, sultans of the sultan of the family of Uthman ibn Sultan Ghazi Khan … may God extend the days of his [happiness] to the day of [judgment?]. The script reverses direction half way through. This page of a Qur'an depicts two types of script: muhaqqaq in the three lines in body of the page, and the kufic script in the upper and lower margins. The page was signed by Ahmad ibn al-Suhrawardi al-Bakri, one of the six celebrated disciples of Yaqut alMusta'simi, a great master of cursive calligraphy. The page was illuminated by Muhammad ibn Aybak. It was completed in the year 1307–8; (Ilkhanid period) in Baghdad. Iraq, Rogers Fund, 1955 (55.44) Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org. This ceramic bowl from the 9th century is an early example of calligraphy as a main element in decorative design. The Arabic word ghibta, meaning happiness, is repeated in two cobalt blue lines in the center of the bowl against a neutral slip background. Bowl, 9th century; Abbasid period (750–1258) Attributed to Iraq Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1963 (63.159.4) Metropolitan Museum of Art, www.metmuseum.org. Sandstone roundel, early 17th century, India. Diam. 18 1/2 in. Edward Pearce Casey Fund, 1985 (1985.240.1) Metropolitan Museum of Art, www.metmuseum.org. This sandstone roundel from the Deccan, (ca. seventeenth century), shows skill in both calligraphy and stonework. The Arabic invocation Yacaziz, "Oh Mighty!" (one of the ninety-nine Most Beautiful Names of God), is repeated eight times in mirror juxtaposition in the thuluth script. An eight-pointed star emerges from the shafts of the letter a, while the z's of caziz, mirrored and knotted, form a heart-shaped ornament. The number eight, aside from its geometrical qualities, points also to eternal bliss and the eight paradises of which the Islamic tradition speaks, thus adding yet another level of meaning. The calligrapher, although working in Deccan, India, is thought to be Persian. Metal engraving This 15th century helmet bears incised Persian engravings decorated with silver. In addition, the metal is stamped with the mark of the Ottoman arsenals, suggesting that it came into Turkish possession as war booty. Helmet, Iran. Steel, engraved and damascened with silver; Rogers Fund, 1950 (50.87) Metropolitan Museum of Art, www.metmuseum.org. This 13th century Egyptian hanging lamp bears several kinds of insignia. It shows entwined bows, symbolizing the Keeper of the Bow, as it also bears the word for the Keeper of the bow: bunduqdar. The inscription, written in the thuluth style, reads: "That which was made for the tomb of the noble, the elevated, / the cAla'i, the Keeper of the Bow, / may Allah sanctify his soul." An inscription on the lamp indicates that it was made for the tomb of the Mamluk emir Aydakin al-cAla'i al-Bunduqdar who died in the 1285. The neck of the lamp shows an unusual mistake -- as the calligrapher misspelled the word bunduqdar to read bunqud-dar. Mosque lamp (ca. 1285) Mamluk, Egypt. Brownish colorless glass, free-blown, enameled, gilded, and stained; tooled on the pontil; H. 10 3/8 in., Max. Diam. 8 1/4 in. Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917 (17.190.985) Metropolitan Museum of Art, www.metmuseum.org. Data and images provided with the courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art (http://www.metmuseum.org) Hassan Massoudy (http://pagespersoorange.fr/hassan.massoudy/) Christina Campbell and Janet Chernela University of Maryland