2013-XC-0047_c4871f6751b8b717fa91fafee01bcf56

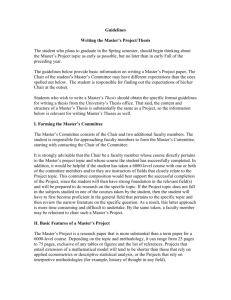

advertisement

Organizing for Commercialization Capability in Microcredit Institutions ORGANIZING FOR COMMERCIALIZATION CAPABILITY IN MICROCREDIT INSTITUTIONS Abstract Contextualized-driven theories for organizations in developing countries are scarce. In this paper, part of this gap is intended to be filled up; building on how some specialized microcredit institutions are organized to create and capture value. These organizations compete at the bottom of the pyramid (BOP) in emerging markets, trying to create social and economic value. The empirical domain in this paper refers to specialized microcredit financial institutions in the Colombian landscape. The theoretical domain relies on the resource based-view of the firm, applied to the mentioned context. The unit of analysis is the commercialization capability in its organizational environment: organizing for commercialization capability. These microcredit social enterprises differ from the traditional banks, because those refer to a “out of the office” commercial human interactions and the deployment of a service relationship between the credit analyst (employee) and the micro-entrepreneur (customer). The main findings are the organizational categories that interact with each other (system) in order to create social and economic value to microentrepreneurs: active corporate governance, microcredit social strategy, management capability in microcredit, relational culture and motivated human talent. Key Words Social enterprise, microcredit, bottom of the pyramid (BoP). Introduction Microcredit institutions co-create value through commercial human interactions with poor micro-entrepreneurs in developing countries. This research is relevant because it addresses a gap in the resource based-view of the firm: contextualized findings in deep poverty environments. This is a qualitative investigation base in a multiple case approach. This is why I have tackled the phenomenon from the perspective of the internal actors in the organization, which means that interviews are the main source of data, however, I have triangulated them with documents and observations. Firms develop and deploy specific resources and capabilities to compete in different economic, social and geographical contexts. However, there is little research understanding how organizations configure their resources and capabilities in specific contexts in order to create value for customers (Sirmon, Hitt & Ireland, 2007), and especially for those at the bottom of the pyramid (BoP) –low income consumers- in developing countries (Seelos & Mair, 2007). These specificities around BoP consumers in emerging markets- have also triggered a new academic research field that had its Organizing for Commercialization Capability in Microcredit Institutions tipping point in 2004 with Prahalad´s book The fortune at the bottom of the pyramid (Prahalad, 2004). Microcredit practices have been extensively studied from the financial and economic perspectives. A huge amount of academic literature has been related to financial models for firms and microcredit impact in economic development. However, the organizational, strategic and marketing perspectives have been understudied. This fact is an additional gap in the literature I want to fill up with this research. Under this view, it is relevant to research microcredit organizations that configure their resources and capabilities in order to structure a value creating commercialization capability, based on the human interaction between the seller (credit analyst) and the customer (micro-entrepreneur). So, the main research question: How do microcredit Colombian social enterprises organize themselves for configuring their commercialization capability? The conceptual domain relied on the resource based-view of the firm (RBV) theory and the relationship marking (RM) theory. They were the lens to approach to the research questions and our cases. These two theories are blended here in order to create a conceptual framework for iterating with the empirical domain supported on a qualitative methodology. I derivate an emergent contextualized model to explain how microcredit social enterprises organize for building the commercialization capability. Literature review Firms´ superior performance can be analysed from their specific resources and not only through products (Wernerfelt, 1984). In other words, firms´ strategy and performance, when creating value through competitive advantages, can be explained through their specific resources (Barney, 1991). Resources are classified as tangible and intangible (Wernerfelt, 1984; Barney, 1991; Hall, 1993). Some examples of tangible resources are cash, equipment, and buildings. Examples of intangibles resources are organizational culture, copyrights, know-how, and data bases (Hall, 1993). Otherwise, resources that lead to a competitive advantage are rare, valuable, immobile, durable and inimitable (Barney, 1991). Capabilities are functional skills or routines that combine and coordinate resources (Grant, 1991; Helfat & Peteraf, 2003). One capability for example is service delivery. Resources and capabilities can be owned by firms, but also have access to them through third parties (Helfat & Peteraf, 2003).Thus, under this framework, strategy is understood as a set of resources and capabilities that exploit opportunities in the competitive landscape and allow the firm to get an above average performance (Grant, 1991). However, resources and capabilities should be adapted to different contexts in order to create the adequate value to customers (Sirmon et al., 2007). Organizing for Commercialization Capability in Microcredit Institutions In terms of the bottom of the pyramid markets in developing countries, little research has been done through RBV perspective (Seelos & Mair, 2007). Thus, in this paper, the RBV and the BoP markets are brought together for understanding how social enterprises organize their commercialization capability in circumstances of deep poverty. According to Prahalad & Ramasvamy (2004), firms should orient their business models, structures, systems and processes towards the co-creation of value with costumers. For these authors, value is co-created in the interaction with customers and consumers. Thus, the organizational configuration, in this case, understood as resources and capabilities combinations, should be oriented to cocreate value to customers (Sirmon et al., 2007) and with customers (Prahalad & Ramasvamy, 2004). The organizational conformation must be constructed under a customer-oriented framework. On the other hand, relationship marketing theory (RM) is a perspective that sheds light on how companies attract, develop and manage commercial relations with individual customers (Berry, 1995; Morgan & Hunt, 1994). Those relationships have been considered resources (“relational resources”) on which competitive advantages rely or emerge (Hunt, 1997). Under this framework of high employeecustomer contact services (Berry, 1995), managing relationships take a special interest. This is the case of the microcredit industry in developing countries. RM has developed several constructs that have special impact when applying them to microcredit services, where the human interaction between the credit analyst and the micro-entrepreneur is frequent, face-to-face, and deploy outside the bank´s branches. In other words, microcredit is a business built up “on the street”, at the micro-entrepreneurs´ homes, the place where normally micro-businesses also take place. The first RM relevant construct in this research is the “relational benefit” (Gwinner, Gremler & Bitner, 1998). This concept implies that commercial relations go beyond the simple transaction and include the value created from long lasting relationships (Gwinner et al., 1998). In the case of microcredit, this means that firms give some additional benefits for clients besides simply “selling a credit”. This approach includes into the business model the benefits that the customer (micro-entrepreneur) derives from the personalized relationships with firms and their sellers (credit analyst). Between the human beings that frequently interact with each other (employees and customers) emerge some sort of friendship that has been call “commercial friendships” in the service RM academic literature (Price & Arnould, 1999). Firms develop and deploy specific resources and capabilities when competing at the bottom of the pyramid markets (BoP) in developing countries (Seelos & Mair, Organizing for Commercialization Capability in Microcredit Institutions 2007), and configure their organizational components in a specific way in order to create and capture value when interacting with individual customers (commercialization capability). Social enterprises (SE) create social and economic value simultaneously (Dees, 1998). A business model with high social impact is deployed though these organizations (Dees, 1998). It is a business model where both economic and social value are created, and this is the argument to call them “hybrid organizations” (Mair & Noboa, 2003). In sum, resources and capabilities in contexts of deep poverty in developing countries have been understudied (Sirmon et al., 2007; Seelos & Mair, 2007) as well as the relationships developed by social enterprises with their individual customers in order to create social and economic value simultaneously. In this point, “relational benefits” and “commercial friendships” play an important role to understand this topic. Microcredit has been addressed from the economic and financial perspectives, but has been understudied from the organizational, strategy and marketing perspectives. Thus, to tackle these gaps, I place this research in the frontier or boundaries between the organizations and marketing fields. Methods This qualitative study aims to develop a grounded theory (Strauss & Corbin, 1990) from a multiple-case design through the literal replication logic among a series of cases (Eisenhardt, 1989; Yin, 2003). This means that each case is treated as an experiment to confirm or disconfirm the observations found in the previous cases (Eisenhardt, 1989; Yin, 2003). A unit of analysis has been chosen: The commercialization capability in the organizational context. Thus, this research fits in Yin´s type 3 -multiple-case design with a unit of analysis- (Yin, 2003, pp. 39-53). This qualitative approach has been chosen due to the nature of the research question -“how” for contemporary events within contextual conditions- (Yin, 2003, pp. 7-9 and p. 22) and to the lack of academic literature (incompleteness) for this specific topic (Eisenhardt, 1989; Golden-Biddle & Locke, 2007) and empirical domain. Sampling A purposeful sampling (Miles & Huberman, 1994; Patton, 2002, pp. 230-242) was conducted, taking into account that chosen organizations fitted adequately in the research question purpose. Moreover, this is being combined with the possibility to gather rich information from the settings and to accomplish the replication logic through “multiple experiments, with similar results (literal replication)” (Yin, 2003, p. 53). The a priori informants´ willingness to collaborate with the investigation has Organizing for Commercialization Capability in Microcredit Institutions also been an important matter (site availability1). Each CEO was contacted through a Colombian non-profit organization within the industry that plays the role of a lender for micro-financial institutions. This fact has allowed having the opinion of an expert about how well the cases fitted to the research objectives, including a reputational case selection (Miles & Huberman, 1994, p. 28). Besides, this person has helped the researcher to have access to the key informants and get the green light from the chosen social enterprises. Four criteria were used to choose these cases in the Colombian context: 1) social impact (outreach and growth), 2) auto-sustainability (financial viability), 3) longevity (at least 10 years), 4) recommendations made from a savvy expert in the industry. Likewise, three chosen organizations were ranked by Forbes2 magazine within the world´s top 10 performance micro-financial institutions. Data sources and collection The data was collected from three main sources of evidence: 1) Interviews as the primary data, 2) archival data (documents), and 3) non-participant observation. Interviews were conducted in a top-down approach with semi-structured templates (protocol guide) with open-ended questions. This implies collecting data from different perspectives and levels within the organization (Leonard-Barton, 1990). Documents were given to the researcher by each one of the informants during interviews: Power points, statistics, financial statements, publicity material, company´s memories, codes, manuals, magazines, newspaper articles, etc. Organization´s Web sites were visited. During the interviews (being within the organization setting) field notes were taken with details of the interactions and the researcher´s impressions and observations. Descriptive narratives (histories) were written by the researcher, including and selecting quotes from the informants and triangulating different sources (Eisenhardt, 1989). Four descriptive case reports (narrated neutrally), reviewed and approved by the informant organizations, give the research a broader validity in terms of reducing the researcher´s subjectivity (Yin, 2003). Data analysis and conceptualization As mentioned above, the general chosen strategy integrates the grounded theory, the multiple case studies for analyzing the qualitative data, and the narrative and visual strategy to present the findings. For general validity, this research use different sources of data and triangulate them (different informants, documents and nonparticipant observations). Moreover, the organizations and the key interviewees According to Leonard-Barton (1990, p. 263), this is a very important criteria and includes commitment and cooperation. The top 50 microfinance institutions. Forbes: http://www.forbes.com/business/2007/12/20/microfinance-philanthropy-credit-bizcz_ms_1220microfinance_table.html. Accessed: January 10th, 2008. 1 2 Organizing for Commercialization Capability in Microcredit Institutions reviewed the case reports, activity that increases validity (Yin, 2003) or credibility (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). The patterns and the relationships among categories will have to emerge from the evidence during the cross-case analysis, which was made, as mentioned, through the literal replication logic (Eisenhardt, 1989; Yin, 2003). This replication technique, on the other hand, is our support for external validity (Yin, 2003). However, this research doesn’t look for an external generalization understood as a universal theory derived from a statistically representative sample, and rather it has been designed under the replication logic and qualitative data interaction with the theoretical framework looking for an analytic generalization (Miles & Huberman, 1994; Yin, 2003, pp. 32-34) or internal generalization (Maxwell, 1996). Identifying and explaining the relationships among categories completed the construction of an emergent contextualized theory. The emergent model A performance model emerged from the qualitative data. This model explains how microcredit social enterprises organized the main organizational components (in terms of resources and capabilities) in order to deploy the commercialization capability. This model is depicted by Figure 1: Microcredit social strategy Relational Culture Commercialization capability Active corporate governance Social and economic value creation Motivated human talent Management capability in microcredit Figure 1. Organizing for commercialization capability Conclusion Organizing for commercialization capability in microcredit institutions implies several organizational components oriented to structure the human commercial interaction. These causal components are the following: Social strategy, management Organizing for Commercialization Capability in Microcredit Institutions capability, relational culture, active corporate governance and motivated human talent. They are combined to deploy a social and economic creating value service relationship with customers. I argue that in the case of microcredit, the space where value is created relies on the human interaction between the credit analyst and the micro-entrepreneur (commercial friendship with relational benefits), because it is a process where collaterals can be exchanged for information and deep knowledge of individual clients, allowing their inclusion into the economic system -human empowerment-. Contributive motivation seems to be distributed throughout the microcredit organization. This means that senior managers and collaborators make sense of their work in terms of its impact on other people, in this case, on micro-entrepreneurs. This propels a pro-social behavior: serving and empowering the low-end segments of customers with respect. Future work for this article requires going deeper in the qualitative data in order to comprehend the relationships among these organizational components. This means to find in an accurate way, for example, the link between culture and the commercialization capability or the link between strategy and culture, etc. This is important for theorizing and stating propositions. Some limitations must be mentioned. This work has been done in a specific context: Colombia. Findings are limited to microcredit social enterprises in this empirical domain. I refer here to microcredit and not to microfinance. Microcredit is about loans, and microfinance is about loans, savings and insurance. The social enterprises I study here were microcredit institutions. On the other hand, “richness” and “replication logic” need further work in this article. For future research, I think this research could be replicated in other Latin American countries, so in this way a Latin American model could emerge. I also think the model depicted in Figure 1 could be tested through a quantitative approach. Finally, some ethical elements must be mentioned. All the informants consented to give the interviews and were authorized by their superiors. I kept their anonymity and I did everything to protect their privacy and their integrity. The informants agreed to use their comments for writing research cases. References Barney, J.B (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17 (1), 99-120. Berry, L. (1995). Relationship marketing of services –Growing interest, emerging perspectives. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 23 (4), 236-246. Cardona, P. y Rey, C. (2005). Dirección por misiones. Barcelona: Deusto. Organizing for Commercialization Capability in Microcredit Institutions Dees, J. G. (1998). Enterprising nonprofits. Harvard Business Review, 76 (1), 12. Eisenhardt, K. (1989). Building Theories from Case Study Research. Academy of Management Review, 14 (4), 532-550. Golden-Biddle, K. and Locke, K. (2007). Composing qualitative research. Thousand Oaks: Sage. Grant, R. (1991). The resource based theory of competitive advantage. California Management Review, 33 (3), 114-135. Gwinner, K., Gremler, D. y Bitner, M.L. (1998). Relational benefits in services industries: The customer´s perspective. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 26, 101-114. Hall, R. (1993). A framework Linking Intangible Resources and Capabilities to Sustainable Competitive Advantage. Strategic Management Journal, 14 (8), 607-618. Helfat, C. y Peteraf, M. (2003). The dynamic resource-based view: capabilities lifecycles. Strategic Management Journal, 20 (10), 179-191. Hunt, S. (1997). Competing through relationships: Grounding relationship marketing in Resource-Advantage Theory. Journal of Marketing Management, 13, 431-445. Leonard-Barton, D. (1990). A dual methodology for case studies: Synergistic use of a longitudinal single site with replicated multiple sites. Organization Science, 1 (3), 248-266. Lincoln, Y. y Guba, E. (1985). Naturalistic enquiry. Beverly Hills: Sage. Mair, J. and Noboa, E. (2003). Emergence of Social Enterprises and Their Place in the New Organizational Landscape. IESE Working Paper No. D/523. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=462284, accessed on may 17, 2008. Maxwell, J. A. (1996). Qualitative research design: An interactive approach. Thousand Oaks: Sage. Miles, M.B. and Huberman, A.M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis. Thousand Oaks: Sage. Morgan, R. y Hunt, S. (1994). The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. Journal of Marketing, 58, 20-38. Patton, M.Q. (2002). Qualitative research & evaluation methods. Thousand Oaks: Sage. Pérez, J. A. (2000). Fundamentos de la dirección de empresas. Madrid: Rialp. Porter, M. (1996). Estrategia competitiva. México: CECSA. Prahalad, C.K. (2004). The fortune at the bottom of the pyramid. New Jersey: Wharton School Publishing. Prahalad, C.K. y Ramaswamy, V. (2004). The future of competition. Co-creating unique value with costumers. Boston: Harvard Business School Press. Price, L. y Arnould, E. (1999). Commercial friendships: Service provider-client relationships in context. Journal of Marketing, 63, 38-56. Schein, E. (1985). Organizational culture and leadership. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Seelos, C. y Mair, J. (2007). Profitable Business Models and Market Creation in the Context of Deep Poverty: A Strategic View. Academy of Management Perspectives, 21 (4), 49-63. Sirmon, D.G, Hitt, M.A., e Ireland, R.D. (2007). Managing firm resources in dynamic environments to create value: Looking inside de black box. Academy of Management Review, 32 (1), 273-292. Organizing for Commercialization Capability in Microcredit Institutions Strauss, A.L. and Corbin, J.M. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Newbury Park: Sage. Wernerfelt, B. (1984). A resource based view of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 5 (2), 171-180. Yin, R.K. (2003). Case study research: Design and methods. London: Sage.