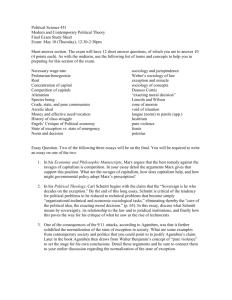

Agamben K - Open Evidence Project

advertisement

Agamben K

1nc

1nc

Modern surveillance reform is smoke and mirrors --- the state of exception will

continue to operate indefinitely

Douglas 9 (Jeremy – independent scholar, “Disappearing Citizenship: surveillance and the state of

exception,” in Surveillance & Society, Volume 6, Number 1, 2009, p. 32-42,

http://library.queensu.ca/ojs/index.php/surveillance-and-society/article/viewFile/3402/3365)

However, although many of the concepts and techniques we see at work in the camp are not fundamentally different today, not everything has remained the same.

The importance of a juridical- political system that acts according to the state of exception, or suspension of the law, is evident in the emergence of recent

totalitarian and ‘democratic’ permanent states of emergency; for example, the UK and the US have normalised the exception through the passing of ‘laws’

(Terrorism Act, Patriot Act, etc.) that essentially nullify the application of normal laws protecting human rights, while still holding them technically ‘in force’. We see

also that these ‘exceptional’ laws go hand in hand with increased surveillance, both of which are tactics that establish control of the population. Yet what remains to

be analysed is the relation(s) between surveillance, territory, and the state of exception - how does surveillance allow for the rise of the state of exception and the

camp? And, more broadly, how are all there concepts integrated in an art of government? Surveillance

must be regarded as the point at

which the camp and the bare of the state of exception intersect in the governmental control of the

population. Defining the Terms: Foucault and Agamben Although Michel Foucault wrote a book (Discipline and Punish) that dealt extensively with one

method of surveillance, the panoptic, his more useful contribution to the theory of surveillance comes from his study of ‘governmentality’, or the ‘art’ of governing.

In the course of his 1970s lectures at the College de France, Foucault underwent a significant shift in the emphasis of his theory, moving from the power- territory

relationship of sovereignty to the politico-economic governmentality of population; the concept of sovereignty concerned with maintaining power and territory is a

dated pre-modern concept, and what needs to be analysed now is the governing of a population though various circulatory (that is, relational) mechanisms: “it is

not expanse of land that contributes to the greatness of the state, but fertility and the number of men” (Fleury quoted in Foucault 2007, 323). In other words, what

is emerging in Foucault’s writings, beginning with The History of Sexuality Vol 1, is the concept of biopolitics: “the management of life rather than the menace of

death” (Foucault 1990, 143). Broadly, what is taking place in Foucault’s works and lectures in the mid to late 1970s is his description of the differences (not

transitions) between “sovereignty, discipline, and governmental management” (Foucault 2007, 107). The

essential goal of sovereignty is to

maintain power, which is achieved when laws are obeyed and the divine right of the throne is

reaffirmed. ‘Power’ is the essential defining component of sovereignty, while ‘government’ is more or

less just an administrative component within the sovereign state

- a component that is the function of the family; the family, oikos, in ancient Greece was the private

management (government) of economic matters where the father ensured the security, health, wealth, and goods of his wife and children, while the polis was the public realm where man realised his political significance in striving for “the good life”. The rise of government in the

sixteenth century is marked by this family government model being “applied to the state as a whole” (ibid, 93), as well as by the rise of “mercantilism” - the former not realizing its full scope and application until the eighteenth century and the latter being a stage of rasion d’etat between

sovereignty and governmentality. However, when the art of governing becomes the predominant ‘goal’ of the state in the eighteenth century, the family is relegated to the position of an “instrument” and population emerges as the “main target” (ibid, 108) of the government (territory is

the main target of sovereignty insofar as a sovereign defines itself according to its territory, while government defines itself in term of its population). With population as the central concern for government, other institutions and sites - such as territory, the family, security (military),

police, and discipline - all become “elements” or “instruments” in the management of the population - these biopolitical tactics are what primarily distinguish governmentality from sovereignty. Conduct and Subjectivization Foucault wants to situate bio-power in the multiplicity of

relations within the overarching structure of the state, and therefore not discard the notion of ‘power’ but instead couch it in terms of governmentality. Biopolitics is produced in the relations between biological life and political power (bio-power), which is possible when a population is

confronted with and in relation to the biopoliticizing (not to be confused with disciplining) techniques of institutions, territory, police, security, and surveillance; rather than positing a sovereign-people dialectic (which Agamben tends to do), Foucault wants to complicate the notion of

biopolitics by accounting for a state that “spreads it tentacles” (Virilio 1997, 12) through its various instruments and tactics. It seems as though, with the beginning of a governmentality discourse developing in the Security, Territory, Population course, Foucault feels he has said enough

about biopolitics as such and can now move towards the art and techniques of governmental and subjective “conduct”, in which biopolitics is implicit. Yet what emerges is, on the one hand, a theory of the top-down management of a population that is controlled through governmental

mechanisms such as statistics-guided surveillance and police practices, and, on the other hand, the bottom-up subjectivization of population through the regulation of actions confronted with state power relations; this may also be regarded as biopolitical population control and

individualizing discipline, respectively. These two streams of governmentality surface in Foucault’s later writings from time to time, but he never clearly reconciles the art of government and subjectivization. This subjective ‘conduct’ or ‘governing the self’ is a self-disciplining that is made

possible through the knowledge of oneself as ‘the other’, as the object of an unseen seer (as is discussed with the panoptic model in Discipline and Punish). This self-conduct, however, is framed in terms of the problematic of government that uses the power relation techniques of

governing others to govern themselves (Foucault 2000, 340-342); but again, where do these two points converge and differ? It seems as though we must look to surveillance to answer this question. We know that surveillance is certainly a governmental ‘technique’ for the management

and control of the population, but we also see that subjectivization is only possible via surveillance, as just mentioned with the panoptic model. However, panoptic surveillance is an ancient notion, developed at least as far back as EBII, sometime around 3000-2650BC (Yekutieli 2006, 78).

The relation between the seer and the subject is no longer that of a physical perspective from a point fixe, nor is it localised in a contained space, as with Bentham’s prison model. Rather, as Paul Virilio would argue, surveillance is making the traditionally confined space of the camp the

very centre of the city. However, before examining the juridical-political applications of this notion, we must understand Giorgio Agamben’s conception of biopolitics in terms of “bare life” and “the state of exception”. Redefining Biopolitics Following and ‘completing’ Foucault’s discussion

of biopolitics, Agamben seeks to further explore the relation between state power and life, not in terms of governmentality, but rather, in terms of sovereign power. That is, what affect(s) does the state have upon the lives of citizens in relations of power and control? In a sense,

Agamben’s position is formulated in accordance with what Arendt and Foucault failed to do: Agamben completes Arendt’s discussion of totalitarian power, “in which a biop olitical perspective is altogether lacking” (Agamben 1998, 4), and completes Foucault’s discussion of biopolitics,

which fails to address the most paradigmatic examples of modern biopolitics, such totalitarianism and the camp. This revision of Arendt and Foucault is achieved through the exemplification of the state of exception and bare life, which find their ultimate realizatio n in modern examples of

the camp. But first, it is necessary to understand how Agamben arrives at this conclusion. In Politics, Aristotle distinguishes between natural, simple life , Zoe, and political life, bios. Zoe is private life confined to the home, oikos, while bios is life that exists in the public (political) realm of

the city, the polis; the former is life regulated by the economy of the family, while the latter is “good life” regulated by the state. It appears, then, that Zoe and bios are mutually exclusive, and man moves from an animal life to a distinct political life, as Aristotle seems to argue. Foucault

picks up on this Aristotelian animal/political life when he writes of the “threshold of biological modernity” (Foucault 1990, 143), in The History of Sexuality, and modifies it to reflect the transition from a politics of the power-limit of death to the politicization of biological (or, more

accurately, zoological - i.e. Zoe-logical) life: “For millennia, man remained what he was for Aristotle: a living animal [Zoe] with the additional capacity for a political existence [bios]; modern man is an animal whose politics places his existence as a living being in question” (ibid). The

distinction between Zoe and bios is called into question; what were once two distinct forms of life are now indistinguishable - biology has become political and politics has become biological, giving rise to biopolitics. Agamben’s claim, however, is that Foucault, Arendt, and others have

misread Aristotle; in interpreting Aristotle, they believe that “the human capacity for political organization is not only different from but stands in direct opposition to that natural association whose center is the home (oikia) and the family” (Arendt 1998, 24, author’s italics). On the

contrary, the simultaneous inclusion and exclusion of life in politics - that is, the production of a biopolitcal life - is the “original activity of sovereign power” (Agamben 1998, 6). Although Aristotle appears to present zoe and bios as polar forms of life - animal versus political - he provides

indications that the supposed exclusion of natural life from the political realm is at the same time its inclusion, and therefore the originary biopolitical act: “we may say that while [the polis] grows for the sake of mere life, it exists for the sake of a good life” (Aristotle quoted in Politics,

Metaphysics, and Death, 3). This implies, as Agamben notes, that natural life had to “transform” itself into political life; political life is not “in direct opposition” to natural life, then, but is born of it. The very notion of bios is itself only possible through its inclusion of zoe - “Nation-state

means a state that makes nativity or birth (that is, naked human life) the foundation of its own sovereignty” (Agamben 1998, 20); biopolitics is this indistinction between private life and public life, an “undecidability...between life and law” (Agam ben 2005, 86). Bare Life and the State of

Exception This conception of biopolitics as an ancient and founding notion of sovereignty needs to be distinguished from what Agamben terms “bare life” or “homo sacer” (life that may be killed but not sacrificed). Biopolitical life, as mentioned above, is still within the juridical-political

realm, but bare life is that which is banished from the polis. It is not pure political life as such, but a life that exists at the threshold between zoe and bios. Bare life is the indistinguishability between natural life and political life - a life that exists neither for the sake of politics nor for the

sake of life: “bare life.. .dwells in the no-man’s-land between the home and the city” (Agamben 1998, 90). It is a life that is banished from politics - outside of law - but included in its exclusion - still within the ‘force of law’: The ban is essentially the power of delivering something over to

itself, which is to say, the power of maintaining itself in relation to something presupposed as nonrelational [i.e. bare life]. What has been banned is delivered over to its own separateness and, at the same time, consigned to the mercy of the one who abandons it - at once excluded and

included, removed and at the same time captured. (ibid, 110) How is this possible? How can bare life be excluded and included? What implications would this have? In order to understand how bare life is produced and how it can exists both within and outside of the polis, it is necessary

to introduce another concept: state of exception. This notion is derived, by in large, from Carl Schmitt’s book Political Theology, as well as from a fairly extensive debate between Walter Benjamin and Schmitt concerning the nature of the state of exception. The state of exception is a

“suspension of law”, which is usually instituted during a period of war or another state of emergency: “The exception, which is not codified in the existing legal order, can at best be characterized as a case of extreme peril, a danger to the existence of the state, or the like” (Schmitt 1922,

6). Under the state of exception there becomes a ‘threshold’ between law that is in the norm but is suspended and law that is not the norm - i.e. not necessarily part of the juridical order - but is in force; so, in the state of exception there appears this “ambiguous and uncertain zone in

which de facto proceedings, which are themselves extra- or antijuridical, pass over into law, and juridical norms blur with the mere fact - that is, a threshold where fact and law seem to become undecidable” (Agamben 2005, 29). What needs to be underlined here is the relation between

the state of exception and bare life. This point is absolutely crucial for Agamben and for understanding the role of governmental surveillance: the state of exception opens up the possibility of bare life and of the camp, where bare life is outside law but constantly exposed to violence and

“unsanctionable killing” (Agamben 1994, 82). Agamben’s position can be understood in the triadic relation ‘state of exception-camp-bare life’; the ultimate power of the sovereign, and the complete dissolution of democracy into totalitarianism - two political systems that, according to

Agamben, already have an “inner solidarity” (ibid, 10) - happens at the point when the state of exception becomes the rule and the camp emerges as the permanent realization of the indistinguishability between violence and law, to which we all, as homines sacri, are exposed. The

paradigmatic example is, of course, Nazi Germany; but what remains to be seen is how this triad can be applied to our current political milieu. The Potentiality of/for Violence Perhaps the closest Agamben comes to discussing the relations between the state of exception and surveillance

is his 11th January 2004 article in Le Monde, entitled, “No to Bio-Political Tattooing” (Agamben, 2004). This article comes as a result of Agamben’s cancellation of a course he was scheduled to teach at New York University that March. The reason he cancelled the course was because he

modern security and

surveillance techniques are emerging as the new paradigm (though not to the extent of the camp) of the state of

exception, in which the exception has become the rule: There has been an attempt the last few years to

convince us to accept as the humane and normal dimensions of our existence, practices of control that

had always been properly considered inhumane and exceptional. Thus, no one is unaware that the control

exercised by the state through the usage of electronic devices, such as credit cards or cell phones, has reached

was denied entry to the US as a result of his refusal to provide biometric data as part of post-9/11 US security measures. The resulting article is mostly a brief, simplistic version of his book Homo Sacer, but Agamben does imply that

previously unimaginable levels. (Agamben 2004) Electronic and biometric surveillance are the tactics through which the

government is creating a space in which the exception is routine practice. The biopolitical implication of

surveillance is the universalization of bare life: “History teaches us how practices first reserved for foreigners find themselves applied

later to the rest of the citizenry” (ibid). These new control measures have created a situation in which not only is there

no clear distinction between private and political life, but there is no fundamental claim, or right, to a

political life as such - not even for citizens from birth; thus, the originary biopolitical act that inscribes life

as political from birth is more and more a potential de-politicization and ban from the political realm. We

are all exposed to the stateless potentiality of a bare life excluded from the political realm, but not outside the

violence of the law (and therefore still included): “states, which should constitute the precise space of political life, have made the person the ideal suspect, to the

point that it's

humanity itself that has become the dangerous class” (ibid). Making people suspects is

equivalent to making people bare life - it is the governmental (a Foucauldian governmentality rather than an Agambenian

sovereignty I would argue) production of a life exposed to the pure potentiality of the state of exception: “the sovereign

ban, which applies to the exception in no longer applying, corresponds to the structure of potentiality, which maintains itself in relation to actuality precisely

through its ability not to be” (Agamben 1994, 46). Surveillance

is the technique that opens up this potentiality, which

allows for the normalization of the exception. In this particular instance - i.e. biometric data collection and surveillance in the US - the

state of exception as a permanent form of governmentality and the universalization of homines sacri has been brought into existence though the USA Patriot Act

and the Patriot Act II . I have used

the term ‘potentiality’ a number of times precisely to point to the state in which the citizens (or, more broadly,

the population) of a number of countries find themselves. The potentiality I want to analyse can follow two directions: it is the potentiality to be stripped

of citizenship, to be banned, to be abandoned to the law, and to be subjected to political violence, or it is the

potentiality for the government to exercise violence and exceptional law upon the population. So, this potentiality can be both negative and

positive. Although violence becomes indistinguishable from law - or, more specifically, indistinguishable from

surveillance and control - in the state of exception, what needs to be emphasised is that it is not a power relation of

pure violence, but rather, of potential violence. It is important, as Benjamin notes in “Critique of Violence”, to understand that

violence is a function of the power mechanisms of the government (although Benjamin would probably say ‘sovereign’):

“the law’s interest in a monopoly of violence vis-a-vis individuals is not explained by the intention of

preserving legal ends but, rather, by that of preserving the law itself; that violence, when not in the hands of the law,

threatens it not by the ends that it may pursue but by its mere existence outside the law” (Benjamin 1933, 136). The state of exception arises when the population

threatens to take violence away from the law - the

population (rather than individuals per se) are regulated by surveillance methods,

in order to ensure that the ‘norm’ of the law is not threatened; and for this norm to remain ‘in force’ an indefinite period of state

of exception is often exercised, as we see with the example of the USA Patriot Act. The American State of Exception Surveillance and the External 'Threat' This

politics of potentiality is created through the de facto ‘laws’ of state of exception legislation like the Patriot Act. Looking at actual parts of the Act, we can see that it

exemplifies the state of emergency referred to by Agamben et al.; the

‘normal’ law of the state is not abolished but its

“application is suspended” so that it still technically “remains in force” (Agamben 2003, 31). As such, the

suspension of the normal application of the law is done “on the basis of its right of self-preservation”

(Schmitt 1985, 12), so that the exception is that which must produce and guarantee the norm. Obviously then the state of exception is not intended to be anything

more than a temporary safeguarding of normal law. In fact, there can be no ‘normal’ law without the state of exception: “ the

state of exception

allows for the foundation and definition of the normal legal order” (Agamben 1999, 48). The use of the state of emergency to

protect the normality of the legal order dates back at least as far as the Roman Empire. Whenever the Senate believed the state to be in danger, they could

implement the iustitium, which allowed for the consuls “to take whatever measures they considered necessary for the salvation of the state” (Agamben 2005, 41).

Looking back at the Judean Roman camp example, the detention of the Jews could be seen as enacted during an iustitium when Jewish rebelliousness was

endangering the newly acquired Roman providence of Judea. The iustitium, as with other examples of the state of exception, is a void in which the “suspension of

the law” creates a zone that evades all legal definition. Thus, the state of exception is neither within nor outside of jurisprudence - it is “situated in an absolute nonplace with respect to the law” (ibid, 50-51). This ‘non-place’, however, also has literal geographic implications - the ‘place’ of the camp is no longer necessary for

creating bare life. Rather, the mutually operative surveillance and state of exception allow for a city-camp, which maintains control and suspicion over a population

without necessitating borders. But, we must distinguish - and this is relevant for the Roman camp example - between the functionality and mechanization of camps

(see abstract). For example, the Roman camp, prison, border camp, work camp, etc. all have a different functionality - from the suppression of a rebellion to idle

detention - but the mechanizations they employ to carry out this functionality are the same - to monitor and maintain control over a given population by creating

bare life (the reason the population is in a camp in the first place is surprisingly irrelevant). Although the functionality of camps may differ, I want to emphasize that

the mechanizations of power will always employ a structure of surveillance; this is the link between ancient and modern camps. Moving away from ancient

examples of the state of exception and looking at the current American judicial-political situation, Agamben’s central argument in Homo Sacer and State of

Exception is that modern

politics are defined by the permanence of a state of exception in which the exception

becomes the rule, or the norm. An example of this exception-as-the-rule can be seen in an American 2006 CRS Report for Congress on national emergency

powers: “those authorities available to the executive in time of national crisis or exigency have, since the time of the Lincoln Administration, come to be increasingly

rooted in statutory law” (Relyea 2006, 2, author’s italics). It continues: Under

the powers delegated by such statutes [constitutional law,

statutory law, and congressional delegations], the President may seize property, organize and control the means of

production, seize commodities, assign military forces abroad, institute martial law, seize and control all

transportation and communication, regulate the operation of private enterprise, restrict travel, and, in a

variety of ways, control the lives of United States citizens. (ibid, 4, author’s italics). This report alludes to biopolitical powers for one, but also the

ways in which the state of emergency is implemented through a variety of statutes, and not instituted as one bill or act that can be in or out of force en bloc. Rather,

it is becoming more difficult to identify juridical documents that provide state of exception powers that

are clearly distinguishable from ‘normal’ law. The Patriot Act, to be sure, is clearly identifiable from ‘normal’ US law, but The Domestic

Security Enhancement Act 2003 was not passed under that name (nor under the alias ‘Patriot Act II’), but was tacked on to other Senate Bills piecemeal. For

example, some enhanced surveillance measures were not passed under the Patriot Act, but were passed into US Code - under title 50, chapter 36, subchapter I, §

1802 of the US Code: “Notwithstanding any other law, the President, through the Attorney General, may authorize electronic surveillance without a court order

under this subchapter to acquire foreign intelligence information for periods of up to one year”. So, ‘ snooping’

surveillance tactics will still be

part of ‘normal’ law even if the Patriot Act is not renewed; this is what Agamben means when he writes

of the “permanent state of emergency” (Agamben 2005, 2).

There are a few sections of the Patriot Act that are worth discussing in order to demonstrate the modern state of exception, as well as its link

to surveillance and the camp. Under Section 412 of the Act, entitled “Mandatory detention of suspected terrorists”, the Attorney General has the power “to certify that an alien meets the criteria of the terrorism grounds of the Immigration and Nationality Act, or is engaged in any other

activity that endangers the national security of the United States, upon a ‘reasonable grounds to believe’ standard, and take such aliens into custody”. The Attorney General must review the detention every six months and determine if the alien is to remain in detention because of a

continued risk to security. But what remains ambiguous, and allows for the indistinction between law and violence and between police and sovereignty, is this “reasonable grounds to believe standard”. Suffice it to say, without going into greater depth, this ‘standard’ is grounds for racial

profiling and the detention of political opponents. Also, the detention of aliens on a ‘belief’ is the production of bare life, since it is the stripping of rights without reference to a violation under ‘normal’ law; in other words, these “suspected terrorists” are detained without having done

anything wrong, but must be situated in the state of exception camp for those who may threaten the ‘normal’ force of the law - this is the aforementioned void, or ‘non¬place’, of the law. Since these aliens cannot be detained under the normal law, a camp of suspects must emerge in a

national security emergency. What is also telling about this Act is that the ten Titles may be seen as different governmental tactics, networked in one state of emergency act; Titles include, “Enhancing Domestic Security against Terrorism”, “Protecting the Border”, “Strengthening the

Criminal Laws against Terrorism”, and “Increased Information Sharing for Critical Infrastructure Protection”. Foucault would be quick to point out that this Act characterizes the population conducting tactics that define governmentality: policing, disciplining, and security. However, Title II,

“Enhanced Surveillance Procedures”, not only becomes implicit in many of the other areas of the act that discuss “intelligence” and “security”, but also allows the Act to go beyond the protection of the ‘norm’ in a sovereign nation-state through foreign surveillance provisions. Section 214

functions in collaboration with and amends several parts of the Foreign Intelligence Service Act 1978 (FISA) in order to allow for international surveillance activities in order identify suspected terrorists: during periods of emergency (i.e. state of exception), the US invests itself with the

power to collect “foreign intelligence information not concerning a United States person or information to protect against international terrorism or clandestine intelligence activities” (Sec. 214(b) (1)). The detention and surveillance of aliens continues though other mechanisms of

jurisprudence, which, as mentioned, are becoming normalised through bills, acts, etc. that are not designed as state of emergency ‘law’ per se. On 13th November 2001, George W. Bush issued a military order for the “Detention, Treatment, and Trial of Certain Non-Citizens in the War

Against Terrorism”; by ‘certain’ this order means anyone “believed” to be associated with al Qaida (PoTUS, 2001). Like with Section 412 of the Patriot Act, suspected terrorists are to be detained without a court order. Similarly, under the Terrorism Act 2000 in the UK, “A constable may

arrest without a warrant a person whom he reasonably suspects to be a terrorist” (Section 41(1)). As with the US, any person detained under this Act can remain in detainment following and pending a review (Schedule 8, Part II). The Disappearance of Citizenship What we have been

discussing thus far applies to the “indefinite” and “mandatory” detention of aliens, but the Patriot Act and the Terrorism Ac t contain various sections on increased surveillance measures that target aliens and native citizens alike. These surveillance activities include the collection of DNA

from anyone detained for any offence or suspected of terrorism, phone taps, wiretaps for electronic communications, the collection of individual library records (Section 215; this Section in particular has received heavy criticism and debate), the collection of banking and financial records,

and other indirect surveillance methods, such as the collection of biometric data at US borders (as Agamben experienced). However, these universal surveillance methods become much more significant when we consider the proposed increased governmental powers outlined in the

Domestic Security Enhancement Act 2003 (alias, Patriot Act II). Under Section 501 of Patriot Act II the “mandatory dentition” of aliens suspected of terrorism extends to include Americans, who ca n also be stripped of their citizenship and made stateless detainees. As Gore Vidal remarks,

“under Patriot Act I only foreigners were denied due process of law as well as subject to arbitrary deportation...Patriot Act II now includes American citizens in the same category, thus eliminating in one great erasure the Bill of Rights” (Vidal 2003). Section 501, “Expatriation of Terrorists”,

of the Act states: This provision (i.e. Section 501) would amend 8 U.S.C. § 1481 to make clear that, just as an American can relinquish his citizenship by serving in a hostile foreign army, so can he relinquish his citizenship by serving in a hostile terrorist organization. Specifically, an

American could be expatriated if, with the intent to relinquish nationality, he becomes a member of, or provides material support to, a group that the United States has designated as a "terrorist organization,” if that group is engaged in hostilities against the United States. With the power

proposed in this section of the Patriot Act II, the government would be able to produce bare life with both aliens and American citizens - “a process leading to the disappearance of citizenship by transforming the residents into ‘foreigners within’, a new sort of untouchable [homo sacer],

in the transpolitical and anational state where the living are nothing more than the ‘living dead’” (Virilio 2005, 165). We have seen how a permanent state of emergency creates a situation in which foreign residents or visitors can be detained without a court order for a n indefinite period

of time; even greater governmental powers are now aiming at expanding this exposure to the pure power of the juridical-political system to citizens as well. Citizenship and political significance are becoming less fundamental and inalienable ri ghts and more categorizations that are only

maintained though blind adherence to so-called democratic polices, which look more and more like a dictatorial structure (see: Arendt 1973). What should also be mentioned is the production of bare life in foreign states; or, conversely, the loss of political rights to another state power

within one’s own country. The power to detain and expose individuals to pure violence and even death is characteristic of the CIA’s and MI5’s borderless security, policing and surveillance mechanisms, which becomes more evident with the Patriot Act and FISA. This may be seen as

grounds for a debate between sovereignty and governmentality. Is sovereignty concerned, above all, with the territorial nation-state, as Foucault argues (Foucault 2007, 14)? Or, is sovereignty more accurately defined as that which decides on the exception, as Schmitt and Agamben

maintain? Neither of these questions can be properly answered until we understand the relations between sovereignty and foreign states. That is to say, is sovereignty only possible in a contained nation-state, or is it something broader that can be applied to foreign nations and even to

the point of being able to declare a state of exception in a foreign land? But if this latter situation is possible - the suspension of other sovereigns’ law - maybe it is something that should, as Foucault insists, be called ‘governmentality’. What should be understood as common to both

conceptions of sovereignty and governmentality, however, is the production of camp, in which the state of exception reaches its ultimate realization. It should be clear that the Patriot Act and other juridical-political provisions precondition and allow for the continued existence of the

The difficulty with theorizing surveillance is that it cannot be done positivistically - it needs to be

situated within a state system that has a biopolitical relationship with the population through a network

of various techniques and conducting mechanisms. Failing to do so will result in a superficial study of surveillance that neglects the crux

camp. Conclusion

of governmental tactics. On the other hand, accounting for the various relations that condition and require surveillance can make theoretical examinations appear

as though they are not ‘about’ surveillance. But this is certainly not the case. Before we can even ask why a state uses surveillance mechanisms, we need to define

what state structure we are talking about. Following Foucault, governmentality

best describes our current political situation, as

it is above all concerned with managing the internal structure of the state according to a

biopoliticization of the population, rather than maintaining the power over life and death, as is characteristic of sovereign politics.

Governmentality is literally an ‘art’ of governing, in which the population is ‘conducted’ through various relations and tactics employed by the state, such as

institutions, security, statistics, and surveillance. So, governmentality is the structure in which surveillance can operate as one of the arms of state power. When we

move towards the juridical-political situation of the state of exception, we see another area in which surveillance plays a crucial biopolitical role. The

use of

exceptional legal measures in order to protect the ‘normal’ force of law is what defines the state of

exception. The ‘normal’ law that is suspended is often that which guarantees the rights and the citizenship of foreign and national citizens; thus, under an

exceptional juridical situation, individuals with no political significance are produced: bare life. The USA Patriot Act (among other documents) embodies this loss of

rights, production of bare life, and increased surveillance based on a perceived national threat. The

state of exception, Agamben argues, is

becoming more and more the normal course of politics - this is nowhere more exemplary than in the

camp. The camp is the place where bare life is produced and the exception becomes the rule. Yet, the Roman camp in Judea shows us that the emersion of

surveillance in a camp-‘state of exception’- territory structure is nothing new. What is primarily ‘modern’ is not biopolitics (Foucault) or the camp (Agamben), but

the governmental control of the disappearance of citizenship. With

digital technology, the erasure of a definite ‘here’ or ‘there’

means that the localised camp is no longer a paradigmatic ‘place’ where the limit of the state of

exception is realised; rather, the non-place of a population in constant movement is what defines the new non-place of the city camp. Thus,

surveillance is deeply imbedded in and necessary for the governmental system that seeks to be instantly

aware of any potential threats to the state so that it can quash those threats by depoliticizing

‘dangerous’ portions of the population and exposing them to the pure potentiality of the ‘management’

of life.

Refuse to draw lines between what forms of surveilling the population are

appropriate --- instead, refuse the ethic of sovereign power which demands such

control

Edkins and Pin-Fat 5 (Jenny – Professor of International Politics at Aberystwyth University, and

Veronique – Senior Lecturer in politics at Manchester University, “Through the Wire: Relations of Power

and Relations of Violence,” in Millennium - Journal of International Studies 2005, Volume 34, p. 14,

http://mil.sagepub.com/content/34/1/1.full.pdf)

One potential form of challenge to sovereign power consists of a refusal to draw any lines between zoeand bios, inside and outside.59 As we have shown, sovereign power does not involve a power relation in Foucauldian terms.

It is more appropriately considered to have become a form of governance or technique of

administration through relationships of violence that reduce political subjects to mere bare or naked life.

In asking for a refusal to draw lines as a possibility of challenge, then, we are not asking for the elimination

of power relations and consequently, we are not asking for the erasure of the possibility of a mode of

political being that is empowered and empowering, is free and that speaks: quite the opposite. Following

Agamben, we are suggesting that it is only through a refusal to draw any lines at all between forms of life (and

indeed, nothing less will do) that sovereign power as a form of violence can be contested and a properly

political power relation (a life of power as potenza) reinstated. We could call this challenging the logic of sovereign

power through refusal. Our argument is that we can evade sovereign power and reinstate a form of power

relation by contesting sovereign power’s assumption of the right to draw lines, that is, by contesting the

sovereign ban. Any other challenge always inevitably remains within this relationship of violence. To move

outside it (and return to a power relation) we need not only to contest its right to draw lines in particular places, but

also to resist the call to draw any lines of the sort sovereign power demands. The grammar of sovereign

power cannot be resisted by challenging or fighting over where the lines are drawn. Whilst, of course, this

is a strategy that can be deployed, it is not a challenge to sovereign power per se as it still tacitly or even

explicitly accepts that lines must be drawn somewhere (and preferably more inclusively). Although such

strategies contest the violence of sovereign power’s drawing of a particular line, they risk replicating

such violence in demanding the line be drawn differently. This is because such forms of challenge fail to refuse

sovereign power’s line-drawing ‘ethos’, an ethos which, as Agamben points out, renders us all now homines sacri or bare

life.

Security logic guarantees that the world lives in a state of constant crisis and becomes

the justification for a violent state of exception that reduces us to bare life

Agamben 14 (Giorgio – Ph.D., Baruch Spinoza Chair at the European Graduate School, Professor of

Aesthetics at the University of Verona, Italy, Professor of Philosophy at Collège International de

Philosophie in Paris, and at the University of Macerata in Italy, “From the State of Control to a Praxis of

Destituent Power,” transcript of lecture delivered by Agamben in Athens, 11-16-13, published on

Roarmag, 2-4-14, http://roarmag.org/2014/02/agamben-destituent-power-democracy/)

A reflection on the destiny of democracy today here in Athens is in some way disturbing, because it obliges us to think the end of democracy in the very place where

it was born. As a matter of fact, the hypothesis I would like to suggest is that the prevailing governmental paradigm in Europe today is not only non-democratic, but

that it cannot either be considered as political. I will try therefore to show that European society today is no longer a political society; it is something entirely new,

for which we lack a proper terminology and we have therefore to invent a new strategy. Let me begin with a

concept which seems, starting

from September 2001, to have replaced any other political notion: security. As you know, the formula “for

security reasons” functions today in any domain, from everyday life to international conflicts, as a

codeword in order to impose measures that the people have no reason to accept. I will try to show that the real

purpose of the security measures is not, as it is currently assumed, to prevent dangers, troubles or even

catastrophes. I will be consequently obliged to make a short genealogy of the concept of “security”. A Permanent State of Exception One possible way to

sketch such a genealogy would be to inscribe its origin and history in the paradigm of the state of exception. In this perspective, we could trace it back to the Roman

principle Salus publica suprema lex – public safety is the highest law — and connect it with Roman dictatorship, with the canonistic principle that necessity does not

acknowledge any law, with the comités de salut publique during French revolution and finally with article 48 of the Weimar republic, which was the juridical ground

for the Nazi regime. Such a genealogy is certainly correct, but I do not think that it could really explain the functioning of the security apparatuses and measures

which are familiar to us. While

the state of exception was originally conceived as a provisional measure, which

was meant to cope with an immediate danger in order to restore the normal situation, the security

reasons constitute today a permanent technology of government. When in 2003 I published a book in which I tried to show

precisely how the state of exception was becoming in Western democracies a normal system of government, I could not imagine that my diagnosis would prove so

accurate. The

only clear precedent was the Nazi regime. When Hitler took power in February 1933, he

immediately proclaimed a decree suspending the articles of the Weimar constitution concerning

personal liberties. The decree was never revoked, so that the entire Third Reich can be considered as a

state of exception which lasted twelve years. What is happening today is still different. A formal state of

exception is not declared and we see instead that vague non-juridical notions — like the security

reasons — are used to install a stable state of creeping and fictitious emergency without any clearly

identifiable danger. An example of such non-juridical notions which are used as emergency producing

factors is the concept of crisis. Besides the juridical meaning of judgment in a trial, two semantic traditions converge in the

history of this term which, as is evident for you, comes from the Greek verb crino; a medical and a theological one. In the medical tradition, crisis means

the moment in which the doctor has to judge, to decide if the patient will die or survive. The day or the days in which this decision is taken are called crisimoi, the

decisive days. In theology, crisis is the Last Judgment pronounced by Christ in the end of times. As you can see, what

is essential in both

traditions is the connection with a certain moment in time. In the present usage of the term, it is

precisely this connection which is abolished. The crisis, the judgement, is split from its temporal index and

coincides now with the chronological course of time, so that — not only in economics and politics — but in every aspect

of social life, the crisis coincides with normality and becomes, in this way, just a tool of government. Consequently,

the capability to decide once for all disappears and the continuous decision-making process decides

nothing. To state it in paradoxical terms, we could say that, having to face a continuous state of exception, the government

tends to take the form of a perpetual coup d’état. By the way, this paradox would be an accurate description of what happens here in

Greece as well as in Italy, where to govern means to make a continuous series of small coups d’état. Governing the Effects This is why I think that, in order to

understand the peculiar governmentality under which we live, the

paradigm of the state of exception is not entirely adequate. I

will therefore follow Michel Foucault’s suggestion and investigate the origin of the concept of security in the beginning of modern economy, by François Quesnais

and the Physiocrates, whose influence on modern governmentality could not be overestimated. Starting with Westphalia treaty, the great absolutist European

states begin to introduce in their political discourse the idea that the sovereign has to take care of its subjects’ security. But Quesnay is the first to establish security

(sureté) as the central notion in the theory of government — and this in a very peculiar way. One of the main problems governments had to cope with at the time

was the problem of famines. Before

Quesnay, the usual methodology was trying to prevent famines through the

creation of public granaries and forbidding the exportation of cereals. Both these measures had negative effects on

production. Quesnay’s idea was to reverse the process: instead of trying to prevent famines, he decided to let

them happen and to be able to govern them once they occurred, liberalizing both internal and foreign exchanges. “To govern”

retains here its etymological cybernetic meaning: a good kybernes, a good pilot can’t avoid tempests, but if a tempest occures he must be able to govern his boat,

using the force of waves and winds for navigation. This

is the meaning of the famous motto laisser faire, laissez passer: it is not only

the catchword of economic liberalism; it is a paradigm of government, which conceives of security (sureté, in Quesnay’s words)

not as the prevention of troubles, but rather as the ability to govern and guide them in the right

direction once they take place. We should not neglect the philosophical implications of this reversal. It

means an epochal transformation in the very idea of government, which overturns the traditional

hierarchical relation between causes and effects. Since governing the causes is difficult and expensive, it is safer and more useful to try

to govern the effects. I would suggest that this theorem by Quesnay is the axiom of modern governmentality. The ancien

regime aimed to rule the causes; modernity pretends to control the effects. And this axiom applies to every domain, from

economy to ecology, from foreign and military politics to the internal measures of police. We must realize that European governments today gave up any attempt to

rule the causes, they only want to govern the effects. And Quesnay’s

theorem makes also understandable a fact which seems

otherwise inexplicable: I mean the paradoxical convergence today of an absolutely liberal paradigm in the

economy with an unprecedented and equally absolute paradigm of state and police control. If government aims

for the effects and not the causes, it will be obliged to extend and multiply control. Causes demand to be known, while effects can only be checked and controlled.

Vote NEG to utilize the 1AC’s politics of biopolitical crisis as an impetus for radical

transformation

Prozorov 10 (Sergei – Professor of Political and Economic Studies at the University of Helsinki, “Why

Giorgio Agamben is an optimist,” in Philosophy Social Criticism, Volume 36, Number 9, p. 1056-1058,

November 2010, http://psc.sagepub.com/content/36/9/1053.abstract)

The second principle of Agamben’s optimism is best summed up by Ho ̈lderlin’s phrase, made famous by Heidegger: ‘where

danger grows, grows

saving power also’.20 Accord- ing to Agamben, radical global transformation is actually made possible by nothing

other than the unfolding of biopolitical nihilism itself to its extreme point of vacuity. On a number of occasions in

different contexts, Agamben has asserted the possibility of a radi- cally different form-of-life on the basis of

precisely the same things that he initially set out to criticize. Agamben paints a convincingly gloomy

picture of the present state of things only to undertake a majestic reversal at the end, finding hope

and conviction in the very despair that engulfs us.21 Our very destitution thereby turns out be the

condition for the possibility of a completely different life, whose description is in turn entirely devoid

of fantastic mirages. Instead, as Agamben repeatedly emphasizes, in the redeemed world ‘everything will

be as is now, just a little different’,22 no momentous transformation will take place aside from a ‘small

displacement’ that will nonetheless make all the difference. While we shall deal with this ‘small displacement’ in the follow- ing

section, let us now elaborate the logic of redemption through the traversal of ‘danger’ in more detail. It is evident that the danger at issue in Agamben’s

work is nihilism in its dual form of the sovereign ban and the capitalist spectacle. If, as we have shown in the previous sec- tion, the reign of

nihilism is general and complete, we may be optimistic about the pos- sibility of jamming its entire

apparatus since there is nothing in it that offers an alternative to the present ‘double subjection’ . Yet,

where are we to draw resources for such a global transformation? It would be easy to misread Agamben as an utterly utopian

thinker, whose intentions may be good and whose criticism of the present may be valid if exaggerated,

but whose solutions are completely implausible if not outright embarras- sing.23 Nonetheless, we must

rigorously distinguish Agamben’s approach from utopian- ism. As Foucault has argued, utopias derive their

attraction from their discursive structure of a fabula, which makes it possible to describe in great detail a better way of life, precisely

because it is manifestly impossible.24 While utopian thought easily pro- vides us with elaborate visions of a better future, it cannot really lead us there, since its site

is by definition a non-place. In contrast, Agamben’s

works tell us quite little about life in a community of happy life

that has done away with the state form, but are remark- ably concrete about the practices that are

constitutive of this community, precisely because these practices require nothing that would be

extrinsic to the contemporary condition of biopolitical nihilism. Thus, Agamben’s coming politics is

manifestly anti-utopian and draws all its resources from the condition of contemporary nihilism.

Moreover, this nihilism is the only possible resource for this politics, which would otherwise be doomed to continuing the work of negation, vainly applying it to

nihilism itself. Given the totality of contemporary biopolitical nihilism, any

‘positive’ project of transformation would come down

to the negation of negativity itself. Yet, as Agamben demonstrates conclusively in Language and Death, nothing is more nihilistic

than a negation of nihilism.25 Any project that remains oblivious to the extent to which its valorized

positive forms have already been devalued and their content evacuated would only succeed in

plunging us deeper into nihilism. As Heidegger adds in his commentary on Ho ̈lderlin, ‘It may be that any other salvation

than that, which comes from where the danger is, is still within non-safety’.26 Moreover, as Roberto Esposito’s work on

the par- adox of immunity in biopolitics demonstrates, any attempt to combat danger through ‘negative protection’

(immunization) that seeks to mediate the immediacy of life through extrinsic principles (sovereignty,

liberty, property) necessarily introjects within the social realm the very negativity that it claims to battle,

so that biopolitics is always at risk of collapsing into thanatopolitics.27 In contrast, Agamben’s coming politics

does not attempt to introduce anything new or ‘positive’ into the condition of nihilism but to use this

condition itself in order to reappropriate human existence from its biopolitical confinement.28 Thus,

while the aporia of the negation of negativity might lead other thinkers to res- ignation about the

possibilities of political praxis, it actually enhances Agamben’s opti- mism. Renouncing any project of

reconstructing social life on the basis of positive principles, his work illuminates the way the unfolding

of biopolitical nihilism itself pro- duces the conditions of possibility for radical transformation. We can now see

that the state of total crisis that Agamben has diagnosed must be understood in the strict medical sense. In pre-modern medicine, the crisis of the disease is its

kairos, the moment in which the disease truly manifests itself and allows for the doctor’s intervention that might finally defeat it.29 For this reason, the

crisis

is not something to be feared and avoided but an opportunity that must be seized. Similarly, insofar as the

sovereign state of excep- tion and the absolutization of exchange-value completely empty out any

content of pos- itive forms-of-life, the contemporary biopolitical apparatus prepares its self-destruction

by fully manifesting its own vacuity.

2nc topshelf

turns case

The axiom of security has depoliticized society and generated a permanent state of

exception, permitting the extermination of all entities under the cover of political and

economic necessity --- ecological catastrophe, torture, enslavement, and military

conflict are the end-points of a politics built on liberal economics and unprecedented

state and police control --- that’s Agamben

The plan reifies the failed logics at the foundation of the surveillance state --FIRST IS PRE-EMPTION: scenario planning results in threat creation because it relies on

turning possiblities into actualities

Massumi 15 (Brian – Professor of Communication at the University of Montreal, “The Remains of the

Day,” in Emotions, Politics and War, Ed. Åhäll and Gregory, 2015)

This isn't just stupidity or faulty reasoning. There is a perverse logic to it. Because if you accept that it's paramount to respond to threat, and that you have to act in

response to it even if it has not yet fully emerged, or even if it is hasn't really even begun to emerge, then you're facing a real conundrum. If you wait for the

emergence, you'll have waited too long -- too late. A

terrorist threat can strike like lightning. Like lightning it can strike anywhere

and any time. But worse than lightning, it can strike anywhere at any time in any guise. This time it might be planes crashing into

buildings. Next time it might be an improvised explosive device. Or a bomb in a subway. Or anthrax in

the mail. No one knows. This only makes the urgency of action all the more acute. Faced with urgent

need to act in the face of the unknown-unknown of a threat that has not yet emerged, there is only one

reasonable thing to do: flush it out. Poke the soft tissue. Prod the terrain. Stir things up and see what starts to emerge.

Create the conditions for the emergence of threat. Start the threat on the way to becoming a clear and

present danger, and then nip it in the bud with your superior rapid-response capabilities. Make it real so

you can really eliminate it. I'm not saying that the Bush administration consciously decided to make Iraq a staging ground for terrorism. I'm only

saying that the fact that their preemptive actions did in fact do that fits perfectly into the logic of preemption, and says something fundamental about what that

logic implies. It

is fundamental to the logic of preemption to produce what it is designed to avoid. That is the only

way to give its urgent need to "go kinetic" in response to threat something positive to attack. This is what distinguishes preemption from the logic presiding over the

previous age of conflict, the Cold War. The logic of the Cold War was deterrence: making something not happen. The goal, faced with the clear and present danger

of nuclear Armageddon, was to hold it in potential, to make sure the threat was never realized, precisely by refraining from preemptive attack. What was

fundamental to the logic of deterrence was the impossibility of a first strike – exactly what preemption requires. Deterrence

exercises a negative

power. In a way, it's logic is the inverse of the logic of preemption. Its aim is to prevent the unthinkable from happening by

transforming a clear and present danger into a threat, then to hold the threat in abeyance, so that it continues to loom over the present indefinitely, so that it

doesn't follow any action path back to the future. The aim of deterrence aim was to suspend threat. Preemption, by contrast, suspends

the

present. It puts us and our actions in that conditional time-loop of the would have/could have. It hangs us on

a thread of futurity. It does this in order to make the would-have-been/could-have-been a "will-have-been-in-any-case." The job of preemption is to

translate the unknown-unknown into a foregone conclusion. Preemption always will have been right,

because it exercises a positive power, a reality-producing power to make things emerge. There is a word for a

reasoning that is always right regardless of the objective situation, and that always leads a foregone conclusion in any case. The word is tautological. The logic of

preemption is a tautological logic. But that's just the half of it. The

logic of preemption is a tautological logic that has the

power to produce the reality to which it responds. In spite of being tautological, or because of the particular way it is tautological,

preemption works. It operates. It operationalizes the future of threat in a way that really, positively produces a

future. It is an operative logic. I call an operative logic that is positively productive of what will really come to be, an ontopower – "onto-" meaning being. An

ontopower is a power that makes things come to be: that moves a futurity felt in the present, into a

presence in the future. When threat becomes effectively tautological, and power becomes ontopower, everything has changed. We've entered a brave

new world, a new regime of power, and a new political era And yes, the more things change, the more they stay the same. In a recent book, Andrew Bacevich, a lifelong military careerist turned military critic, laments that "since taking office, President Obama has acted on many fronts to adjust the way the United States

exercized that leadership. Yet these adjustments have seldom risen above the cosmetic. … The

global war on terror [begun by Bush has

not only] continued [under Obama] .. it has metastasized." It has turned cancerous. It has turned into a selfdriving tendency that has swept Obama up in it. The operative logic of preemption is not a logic he has

– it has him. It has proven itself a self-propagating historical force, an operative historical logic whose

"rightness" is still, as always, a foregone conclusion. It has proven its ability to continue, as a tendency, across the break between

administrations and the changes on the level of explicitly stated doctrine. I will briefly go into how Bush's 9-11-fueled-"everything-changed" is now Obama's "more

off the same," despite the differences in doctrine, the change in the cast of characters, and the obvious differences in personal quality and leadership style. But

before I do that, I want to draw out a bit more some of the implications of the recentering of war and politics on threat. On the way, I want to respond to an

objection I've left my account open to. The example of Al-Qaeda in Iraq that was central to my argument that preemptive power is a productive power is just one

example. In many eyes it might seem a weak one, since it could be laid to unforeseen collateral effects, and dismissed as a mere anomaly or accident, or simply a

product of a miscalculation. The point I want to make is that in

the operative logic of preemption more-or-less unforeseen

effects are precisely what is and must be produced. If the situation is really one full of unknownunknowns, in a perpetually crisis-ridden, ungraspably complex, increasingly chaotic world, then unforeseen effects

will always accompany any action carried out according to any logic. That's a corrollary of the foregone conclusion. What's

particular about preemption is that makes a virtue of this. It turns this problem into something positive as well. It turns it into

a mechanism that fosters its own continuation and proliferation. It can't make the unknown-unknown known. It can't pre-form

or fore-see the exact nature of the reality it will produce. But if it is ready with fast-adapting rapid response capabilities, it can field the effects it

brings into being, by immediately going kinetic in a follow-up action. When it flushes out threat, it can contrive to keep the

emergence within parameters it can handle, more-or-less. There will be threat again. But if all goes well it will be in more controllable parameters.

Preemption can then re-legitimate itself affectively, and redeploy. In this way, to use the military theory jargon, the

operative logic of preemption "leverages" uncertainty. What preemptive power must do is remain

poised to go kinetic again and again, in serial response to the exercise of its own ontopower. Every time it acts,

it must already be poising itself to act again, with equal urgency. In that way, each of its actions will contain within it the seeds of

the next action, and that action, the action after, so that the deployment of preemption cascades,

bringing its affective legitimation by threat with it, step by step. Preemptive action has become selfdriving. It only stands to reason that if terrorist threat is ever-present and proliferates in unforeseen ways, then the

power mobilized against it must be similarly ever-present and proliferating. ow could anyone argue that we shouldn't

be capable of fielding uncertainty? We must always be poised for threat. We must assume the posture -- even if the stated doctrine has changed. If we sit on our

hands, all it will take to delegitimate a government would be another terror attack that happened on its watch. No

government can afford not to

be in a posture of preemption. We must assume the posture at every moment – we must be poised to go kinetic at a moment's notice, whenever

and wherever in the world that threat is felt to loom. Whenever and wherever. The realignment on time I mentioned earlier ends up driving a a tendency for the

logic set in motion to turn space-filling. The

operative logic of preemptive is not only self-driving; it is self-expanding. We

was in fact used as a terror training ground. Terrorist techniques such as the

improvised explosive device and suicide bombings were perfected there, then carried to the other front,

Afghanistan, where they fueled a resurgent insurgency. The preemptive follow-up response on the part of the US was to expand the

watched this happen. Iraq

use of counter-terrorist tactics that matched the IED attack in terms of their ability to strike by surprise with lightning speed, and to morph themselves to the shape

any kind of circumstance, taking any number of guises. The use of these techniques by the US military exploded. Chief among them were targeted assassinations

using rapidly-deployed special operations forces, and unmanned drone attacks. This

escalation began under Bush, but was taken to

new levels by Obama, who had criticized the war in Iraq and called for its winding down only in order to shift attention to Afghanistan, which he defined

as the "good war" and the right war. The right war overflowed to the wrong side of the border, into Pakistan. The blowback from US crossborder drone attacks and special operations in Pakistan have energized activity elsewhere in the world:

in Somalia, in Yemen. Yet another proliferation. US drone attacks and special ops have followed. Preemptive US military intervention has expanded to

yet another continent. The invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan may be winding down. But the preemptive military posture of the US has only spread. And

nowhere has terrorist threat stopped looming. Last month (July 2011) was the bloodiest for months for US military personnel in Iraq,

and terrorist attacks in Afghanistan picked up spectacularly with the assassinations of the governor of Kandahar province and the mayor of Kandahar city. Even after

the "withdrawal" of US troops from Iraq, there will be a continuing US presence indefinitely into the future, as Obama's Secretary of Defense Robert Gates put it, in

order to "fill the gap in Iraqi Security Force operations." This continuing presence will be in the form of five high-tech compounds outfitted for drone operations and

housing aircraft and armored vehicles for rapid-response forays. The withdrawal from Afghanistan will similarly leave a permanent preemption-ready presence.

That presence has unprecedented reach. According to best estimates, the US preemptive presence stretches across more than 750 bases around the world. The less

focused it becomes on outright invasion, the more spread-out and tentacular it becomes. US special operations forces are now active in no less than 75 countries

around the world and carry out an average of 70 missions a day. The number of countries "serviced" is slated to rise to 120. A key to advisor to General Petraeus,

the commander of US troops in Iraq, then Afghanistan, and now incoming CIA director, was recently quoted marvelling at the reach of this "almost industrial scale

killing machine". Preemption

doesn't go away. It spreads its tentacles. Things change. Boots on the ground may recede as drones

advance, following the rhythms of public opinion and the electoral cycle of politicians' engrossment in domestic affairs. Nation-building might get backgrounded in

favor of targeted assassination campaigns. But the

operative logic of preemption only becomes more widespread and

insidious. The more it changes, the more it stays the same, ever-expanding. To the point that it can be said to become the dominant operative logic of our

times. Preemption octopuses on. Ontopower rules.

—risk da

Current debate reverses the logical burden of proof --- we begin from the presumption

advantages start from 100% risk instead of being built up by zero risk --- this distorts

our risk calculus

Cohn 13 (Nate – politics writer for the NY Times, debate coach at Georgia, “Improving the Norms and

Practices of Policy Debate,” in CEDA Debate forums, 11-24-13,

http://www.cedadebate.org/forum/index.php?action=printpage;topic=5416.0)

The fact that policy

debate is wildly out of touch—the fact that we are “a bunch of white folks talking about nuclear war”—is a damning

indictment of nearly every coach in this activity. It’s a serious indictment of the successful policy debate coaches, who have been content to continue a

pedagogically unsound game, so long as they keep winning. It’s a serious indictment of policy debate’s discontents who chose to disengage. That’s not to say there

hasn’t been any effort to challenge modern policy debate on its own terms—just that they’ve mainly come from the middle of the bracket and weren’t very

successful, focusing on morality arguments and various “predictions bad” claims to outweigh. Judges

were receptive to the sentiment that

disads were unrealistic, but negative claims to specificity always triumphed over generic epistemological

questions or arguments about why “predictions fail.” The affirmative rarely introduced substantive responses to the disadvantage,

rarely read impact defense. All considered, the negative generally won a significant risk that the plan resulted in nuclear

war. Once that was true, it was basically impossible to win that some moral obligation outweighed the (dare I say?)

obligation to avoid a meaningful risk of extinction. There were other problems. Many of the small affirmatives were unstrategic—teams

rarely had solvency deficits to generic counterplans. It was already basically impossible to win that some morality argument outweighed extinction; it was

totally untenable to win that a moral obligation outweighed a meaningful risk of extinction; it made even

less sense if the counterplan solved most of the morality argument. The combined effect was devastating: As these debates are currently

argued and judged, I suspect that the negative would win my ballot more than 95 percent of the time in a debate between two teams of equal ability. But even if a

“soft left” team did better—especially by making solvency deficits and responding to the specifics of the disadvantage—I still think they would struggle. They could

compete at the highest levels, but, in most debates, judges would still assess a small, but meaningful risk of a large scale conflict, including nuclear war and

extinction. The

risk would be small, but the “magnitude” of the impact would often be enough to outweigh a

higher probability, smaller impact. Or put differently: policy debate still wouldn’t be replicating a real world

policy assessment, teams reading small affirmatives would still be at a real disadvantage with respect to reality. . Why? Oddly, this is the

unreasonable result of a reasonable part of debate: the burden of refutation or rejoinder, the

responsibility of debaters to “beat” arguments. If I introduce an argument, it starts out at 100 percent—

you then have to disprove it. That sounds like a pretty good idea in principle, right? Well, I think so too. But it’s really tough to refute

something down to “zero” percent—a team would need to completely and totally refute an argument.

That’s obviously tough to do, especially since the other team is usually going to have some decent arguments and pretty good cards defending each component of

their disadvantage—even the ridiculous parts. So one

of the most fundamental assumptions about debate all but ensures

a meaningful risk of nearly any argument—even extremely low-probability, high magnitude impacts,

sufficient to outweigh systemic impacts. There’s another even more subtle element of debate practice at play. Traditionally, the

2AC might introduce 8 or 9 cards against a disadvantage, like “non-unique, no-link, no-impact,” and then go for one and two. Yet in

reality, disadvantages are underpinned by dozens or perhaps hundreds of discrete assumptions, each of which

could be contested. By the end of the 2AR, only a handful are under scrutiny; the majority of the disadvantage is

conceded, and it’s tough to bring the one or two scrutinized components down to “zero.” And then there’s a

bad understanding of probability. If the affirmative questions four or five elements of the disadvantage, but the negative was still “clearly

ahead” on all five elements, most judges would assess that the negative was “clearly ahead” on the disadvantage. In reality, the risk of the disadvantage has been

reduced considerably. If

there was, say, an 80 percent chance that immigration reform would pass, an 80 percent

chance that political capital was key, an 80 percent chance that the plan drained a sufficient amount of capital, an 80 percent chance

that immigration reform was necessary to prevent another recession, and an 80 percent chance that another recession would cause a nuclear war (lol), then

there’s a 32 percent chance that the disadvantage caused nuclear war. I think these issues can be overcome. First, I think

teams can deal with the “burden of refutation” by focusing on the “burden of proof,” which allows a team

to mitigate an argument before directly contradicting its content. Here’s how I’d look at it: modern policy debate

has assumed that arguments start out at “100 percent” until directly refuted. But few, if any, arguments are

supported by evidence consistent with “100 percent.” Most cards don’t make definitive claims. Even when they

do, they’re not supported by definitive evidence—and any reasonable person should assume there’s at least some uncertainty on matters

other than few true facts, like 2+2=4. Take Georgetown’s immigration uniqueness evidence from Harvard. It says there “may be a window” for immigration. So,

based on the negative’s evidence, what are the odds that immigration reform will pass? Far less than 50 percent, if you ask me. That’s not always true for every card

in the 1NC, but sometimes it’s even worse—like the impact card, which is usually a long string of “coulds.” If

you apply this very basic level of

analysis to each element of a disadvantage, and correctly explain math (.4*.4*.4*.4*.4=.01024), the risk of the

disadvantage starts at a very low level, even before the affirmative offers a direct response. Debaters

should also argue that the negative hasn’t introduced any evidence at all to defend a long list of

unmentioned elements in the “internal link chain.” The absence of evidence to defend the argument that, say, “recession causes

depression,” may not eliminate the disadvantage, but it does raise uncertainty—and it doesn’t take too many additional sources of

uncertainty to reduce the probability of the disadvantage to effectively zero—sort of the static, background

noise of prediction. Now, I do think it would be nice if a good debate team would actually do the work—talk about what the cards say, talk about the

unmentioned steps—but I think debaters can make these observations at a meta-level (your evidence isn’t certain, lots of

undefended elements) and successfully reduce the risk of a nuclear war or extinction to something

indistinguishable from zero. It would not be a factor in my decision. Based on my conversations with other policy judges, it may be possible to pull it

off with even less work. They might be willing to summarily disregard “absurd” arguments, like politics disadvantages, on the grounds that it’s patently unrealistic,

that we know the typical burden of rejoinder yields unrealistic scenarios, and that judges should assess debates in ways that produce realistic assessments. I don’t

think this is too different from elements of Jonah Feldman’s old philosophy, where he basically said “when I assessed 40 percent last year, it’s 10 percent now.”

Honestly, I was surprised that the few judges I talked to were so amenable to this argument. For me, just saying “it’s absurd, and you know it” wouldn’t be enough

against an argument in which the other team invested considerable time. The more developed argument about accurate risk assessment would be more convincing,

but I still think it would be vulnerable to a typical defense of the burden of rejoinder. To be blunt: I want debaters to learn why a disadvantage is absurd, not just

make assertions that conform to their preexisting notions of what’s realistic and what’s not. And perhaps more importantly for this discussion, I could not coach a

team to rely exclusively on this argument—I’m not convinced that enough judges are willing to discount a disadvantage on “it’s absurd.” Nonetheless, I think this is

a useful “frame” that should preface a following, more robust explanation of why the risk of the disadvantage is basically zero—even before a substantive response