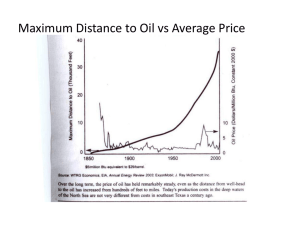

Oil price fluctuations and its effect on GDP growth A case study of

advertisement