Document

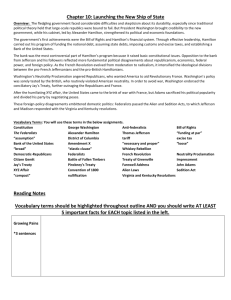

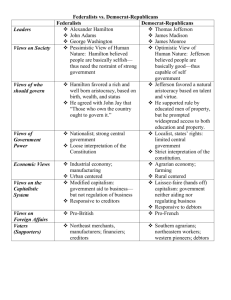

advertisement

Competency Goal 1: The New Nation (1789-1820) – identify, investigate, and assess the effectiveness of political, economic, cultural, and social institutions of the emerging republic. 1.01: Identify the major domestic issues and conflicts experienced by the nation during the Federalist Period 1.02: Analyze the political freedoms available to the following groups prior to 1820: women, wage earners, landless farmers, American Indians, African Americans, and other ethnic groups 1.03: Assess commercial and diplomatic relationships with Britain, France, and other nations Who’s In Charge: Central vs. Local Control Federalism: The U.S. has a federal system of government. Ultimate sovereignty (the power to govern) resides in the people, but the operation of government is divided in a federal structure, among three levels: local, state, and national. In theory, each level is supposed to be sovereign within in its sphere. But as the U.S. grew, tensions arose between localists and nationalists. A group known as the Democratic-Republicans (followers of Thomas Jefferson) and Federalists (followers of Alexander Hamilton) developed into political parties. The parties disagreed over what the U.S. should become. Jeffersonians wanted America to be made up of small republics where a homogeneous (not diverse) polity of small farmers (yeomen) toiled close to the earth and governed themselves. Hamiltonians saw an expansive American industrial empire governed by an educated and wealthy elite, where power was more centralized so that government could protect business to help America compete with European powers. Neither side won completely. What we had was a compromise. American History has been a working out of conflict over who is in charge (central or local), whether it is the fight over tariff and banking policy in the Early National and Jacksonian Eras, or secession crisis of the Civil War, or the economic crisis of the New Deal, or the constitutional battle that was the Civil Rights Movement. Precedent: The first time a thing is done that sets an example or a rule to follow later – George Washington, being the first President of the U.S., established many precedents: (1) to called “Mister;” (2) to serve only two terms despite no constitutional limitation (changed by the 22nd Amendment); (3) to meet regularly with his cabinet; (4) to add the words “so help me God” to the Oath of Office. Images of George Washington: First in War, First in Peace, First in the Hearts of his Countrymen Judiciary Act of 1789: The Constitution created the U.S. Supreme Court, but not lower courts. It left that up to Congress. One of the first pieces of legislation passed by Congress, thus, was the Judiciary Act. It created lower federal courts: the District Courts and Circuit Courts (Appeals Courts). It also gave the courts certain powers not expressly granted under the Constitution. That came back to haunt the Act in the 1803 case of Marbury v. Madison. Tariff Act of 1789: The Constitution gave the new federal government power to tax. This is the first tax imposed by Congress. This is a revenue tariff designed to raise money for the government’s use (particularly to pay off debt). It imposed a 5-to-15 percent tax on all imports. The tariff hurt consumers because it raised prices. Southern exporters opposed the tax because foreign nations often retaliated, imposing high tariffs on the things southerners exported. More troubling still for exporters, tariff rates rose during the 1790s, making the tax closer to a protective tariff. Partisanship: acting in the interests of a political party rather than in the interests of all the country: Political differences grew between 1789 and 1800 as leaders debated whether power should be based in the states or in the national government. The French Revolution widened the gap as the country split between sympathizers with the Revolution and those who saw it breaking down into mob rule. Two parties emerged. The Federalists (including Alexander Hamilton and John Adams) supported a strong central government and wanted an alliance with Britain; and the Democratic-Republicans (a.k.a. Jeffersonian Republicans, and including Jefferson and James Madison) called for state-based governmental authority and supported France. George Washington included men of both views in his cabinet, including Jefferson (Secretary of State) and Hamilton (Secretary of the Treasury). Jefferson’s Notes on Virginia: Jefferson was not an economist; not a practical man. He was a romantic. His romantic view of the American economy appears in his survey of Virginia as governor. It pictured a population of yeomen farmers--self-reliant farmers who owned their land and were tied to it by what they produced on it not by some debt they owed some landlord . Even in bad times, a farmer could at least grow his own food. Factory workers, on the other hand, relied on a wage and did not control their production. If workers were thrown out of work, then they would become a drain on society. Let virtuous farmers have America, Jefferson declared. “Let our workshops remain in Europe.” Hamilton’s Report on Manufactures: Alexander Hamilton’s economic vision for America. It called on government to invest or to spur investment in industries to create a diversified economy of farming, manufacturing, and commerce. It argued government should support manufacturing by imposing a high protective tariff on imports that could be produced in the U.S. This would give U.S. companies a competitive advantage. But it had drawbacks. It hurt consumers by raising prices on necessary goods and forcing them to buy what sometimes were inferior products. It also hurt American exporters, such as farmers who sold cotton to Europe, because foreign countries could retaliate with high tariffs of their own, making American farm products less competitive and less attractive. Hamilton's Economic Plan: Faced with substantial debts, such as those incurred during the Revolutionary War, Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton developed a multi-part plan to establish a viable and expanding American economy (1) Hamilton insisted that the war bonds be paid off in full. This would ensure the credit of the national government and enable the U.S. to borrow money in the future. But many of the original bondholders were small farmers who had sold their bonds to speculators at less than face value. Some advocates for the small farmers said that paying the speculators the full price of the bonds gave them an unfair profit. (2) Hamilton required the federal government to assume the debts of the states. This worked well for states that had not paid off their debts, such as Massachusetts, but it hurt several southern states because they had already paid off their debts and now would have to help pay the debts of other states. Hamilton was insistent. He argued that assumption of debts would strengthen the national government by making creditors dependent on the nation's succeeding if they wanted to be repaid. It would also create a more unified nation. (3) To pay off the debts, the country had to find revenue. Hamilton supported a high tariff that would not only raise money, but also would help U.S. manufacturers be more competitive. He also called for excise taxes--taxes on specific commodities, such as whiskey. (4) Finally, he called for the creation of a national bank. The Bank of the U.S. would act as a depository for federal revenues and would help to control currency and national credit. Controversy of the First Bank of the United States: Whiskey Rebellion (1794): Minor conflict in Pennsylvania resulting from farmers refusing to pay a federal excise tax on whiskey. Farmers roughed up federal marshals; President Washington led troops to put down the rebellion; by the time they arrived, the farmers had dispersed. It showed that the federal government, unlike during Shays' Rebellion, would not tolerate and had the power to end public disturbances Treaty of Greenville: As Americans moved into the Ohio Valley, they again came into conflict with Indians; this time, the Shawnee and Ottawa. General “Mad Anthony” Wayne (a hero of the Revolutionary War), led a force of about 2,600 troops to build Fort Greenville and other outposts to protect settlers. The troops routed the Indians at the Battle of Fallen Timbers. In 1795, the Indians agreed to the treaty that paid them $10,000 per year for their land in southern Ohio and Indiana, and enclaves at Detroit, Chicago, Cleveland, and Vincennes, Illinois. Whites flooded into the region as a result. Pinckney’s Treaty: Treaty negotiated by Thomas Pinckney, minister to Spain, to settle a dispute over the boundary between the U.S. and Spain in West Florida. Spain claimed all land south of the Tennessee River. The treaty settled on a line at 31 degrees latitude, from the Chattahoochee River to the Mississippi. The treaty also granted the U.S. free navigation of the Mississippi River, thus opening up the West to commerce. The French Revolution and The Terror The Napoleonic Wars, 1797-1815 The Problem of Neutrality in Foreign Affairs, 1793-1801 Proclamation of Neutrality: The central plank in George Washington’s foreign policy was to stay out of European conflicts to protect America’s interests. By 1792, the French Revolution had devolved into “the Reign of Terror” as over two years at least 1,285 citizens lost their heads at the guillotine, including King Louis XVI and several revolutionary leaders. And France declared war on Austria and Prussia. Britain went to war with France. Public opinion in the U.S. divided. Jeffersonians sided with France— Jefferson suggested that for revolutions to succeed sometimes you have to spill some blood; U.S. ambassador to France, James Monroe, declared his support for the Revolution in the French legislature, causing his recall by President Washington. Federalists sided with England. Washington knew that for its own good the U.S. had to stay out of it and try to continue to trade with both sides. In 1793, he issued his Proclamation of Neutrality, stating America would remain “friendly and impartial toward the belligerent powers.” France rejected U.S. neutrality, insisting the alliance from the War of Independence was still in effect. Britain refused to accept that the U.S. could truly be neutral when it traded with France. The problem of neutrality plagued U.S. foreign relations for the next twenty years. Citizen Genet: Amid the growing conflict in Europe in 1793, French diplomat Edmond Charles Genet arrived in Charleston and began paying American merchant marines to seize British ships and disrupt trade in the British West Indies. In Philadelphia, the U.S. capital at the time, he conspired to begin a war to take Spanish territories in Louisiana. The Washington administration demanded his recall. When it became clear that he would lose his head if he returned to France, the U.S. gave him asylum provided he stop his mischief. Genet’s actions turned many in the U.S. against France. Although he continued his unyielding support for the French Republic, even Jefferson thought that Genet had gone too far. Jay’s Treaty: Under the Treaty of Paris, Britain was to give up control of land east of the Mississippi. Ten years later, it had not yet done so. President Washington sent Chief Justice of the Supreme Court John Jay to settle that issue and others. To satisfy America’s goals, Jay gave in on several important British demands, notably British definitions of neutrality and contraband trade (closing off trade of food to France), unrestricted traffic on the Mississippi, and free trade between the U.S. and Canada. Jeffersonians criticized the treaty for giving Britain too much, for cutting off trade with France, and especially for giving no protection against impressment of American sailors or protection to U.S. trade under international law. The general public also rejected the treaty. Public opposition was so fierce that when Hamilton defended it, he was literally spat upon. Despite its weaknesses, Washington signed it and pushed it through the Senate in 1795. The greatest effect of the treaty was that it deepened the rift between Federalists and Jeffersonians. John Jay Burned in Effigy Washington's Farewell Address: In 1796, George Washington declared that he would not run for another term, setting the precedent of two terms for President. As he left office, the General gave some advice to the nation. He celebrated American liberty and called for national unity. He also sternly warned against political or regional parties: “To the efficacy and permanency of your Union, a government for the whole is indispensable. . . . The spirit of party . . . unfortunately, is inseparable from our nature, having its root in the strongest passions of the human mind. It exists under different shapes in all governments, more or less stifled, controlled, or repressed; but, in those of the popular form, it is seen in its greatest rankness, and is truly their worst enemy. The alternate domination of one faction over another, sharpened by the spirit of revenge, natural to party dissension, which in different ages and countries has perpetrated the most horrid enormities, is itself a frightful despotism. But this leads at length to a more formal and permanent despotism.“ Referring to the situation in Europe, he insisted that American independence depended on neutrality and flexibility. Americans, he insisted, should not hold a grudge against Britain or insist on permanent links to France. Instead, the U.S. must try to be a friend to all countries: “nothing is more essential than that permanent, inveterate antipathies against particular nations, and passionate attachments for others, should be excluded; and that, in place of them, just and amicable feelings towards all should be cultivated. [Indeed], against the insidious wiles of foreign influence . . . the jealousy of a free people ought to be constantly awake, since . . . foreign influence is one of the most baneful foes of republican government. . . . [We] may choose peace or war, as our interest, guided by justice, shall counsel. . . . It is our true policy to steer clear of permanent alliances with any portion of the foreign world.” Neutrality was declared foreign policy until WWII. The John Adams Administration, 1797-1801 XYZ Affair and Quasi-War: Tensions with France increased as Adams took office. Upset over the ratification of Jay’s Treaty, France rejected Monroe’s replacement. Adams sent a delegation to meet with French Foreign Minister Talleyrand to resolve the issue. Three French agents, referred to as X, Y, and Z, demanded the U.S. give France a loan and pay a bribe to see Talleyrand. Federalists demanded war, saying “millions for defense but not one cent for tribute.” Adams resisted, but soon the two countries were in an undeclared “Quasi- War” in the West Indies. Adams asked Washington to lead an army. As the Hamilton wing of the Federalist Party readied for war, Adams negotiated peace with Napoleon Bonaparte. In the Convention of 1800 (a.k.a. Treaty of Mortefontaine), the French refused to compensate the U.S. for naval losses but agreed to end the 1778 alliance, thus ending the war. Alien and Sedition Acts: Four laws enacted by Federalists to restrict political activities of Republicans . The Alien Acts limited political activity of foreigners who tended to support Republicans; Sedition Acts limited rights of citizens to criticize government, making it illegal to publish or publicly say anything of “a false, scandalous and malicious” nature about the government or any government official. Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions: Jeffersonian Republican response to Alien and Sedition Acts, written by James Madison at the behest of Thomas Jefferson. They argued for nullification, saying a state could make null and void federal laws with which a state disagreed. Nullification renewed the debate over federalism. The “Revolution of 1800” A turning point in American political history, it pitted the Federalist John Adams against Democratic-Republican Thomas Jefferson. Given the Adams administration's failures and a split between Hamilton and Adams, the Federalists lost. Adams refused to attend Jefferson's inauguration, but the peaceful transition of government from one party to its opponent was remarkable for the time. In the election, a problem arose in the Electoral College. Jefferson received the same number of votes as his running-mate Aaron Burr. Under the Constitution, the candidate winning the most votes became POTUS, the second most votes VicePOTUS. With the vote a tie, the election went to the House of Representatives. Federalists hated Jefferson, but they also hated Burr. When Jefferson promised to keep Hamilton's economic plan intact and promised to keep Federalists in government jobs, the Federalists decided that they hated Burr more and voted for Jefferson. To make sure that the problem did not recur, the Twelfth Amendment established that Electors vote for a party ticket or that they declare which vote was for which office. Midnight Judges: Despite losing the election, Adams remained POTUS until March 1801. This meant he still held the power to nominate judges. Federalists also controlled Congress. The appointments continued up to the day Adams left office, earning them the name “midnight judges” meaning at the last minute. Although not one of the last, the most important appointment was of John Marshall for Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. He was Jefferson’s cousin and sworn rival. The Federalists also enacted the Judiciary Act of 1801, adding six new circuit judgeships and reducing the Supreme Court from six justices to five. Jeffersonians cried foul and once they took over repealed the law. Jeffersonians also attacked Federalist judges through the Congress’ power of impeachment. Two judges were impeached. Associate Justice Samuel Chase, however, committed no “bad behavior” other than being a partisan Federalist. The Senate acquitted Chase, setting the precedent that a judge could not be removed from the bench for political reasons. Louisiana Purchase: Land deal, wherein Jefferson bought the Louisiana Territory from Napoleon although he had no clear constitutional authority to do so. The total amount of land bought was imprecise, but it at least included ‘all the lands drained by the waters of the Mississippi River.’ The purchase more than doubled the size of the U.S., extending the nation west to the Continental Divide in the Rocky Mountains. Marbury v. Madison, (1803): Most important U.S. Supreme Court ruling in history. William Marbury was one of the midnight appointments. But the appointment was not delivered before Adams left office. When new Secretary of State James Madison refused to give him the job Marbury sued, asking the court to order Madison to to "hand-over" the appointment. The court, led by Chief Justice John Marshall, ruled against Marbury, saying that although the Judiciary Act of 1789 had given the court the power to issue writs, the Constitution did not give it such power. Thus, part of the Judiciary Act of 1789 was unconstitutional. The ruling established a more important court power: judicial review. The Duel: In 1804, Vice-President Aaron Burr, alienated from the Jeffersonians, ran for Governor of New York without the support of the Republican Party. Again he clashed with Alexander Hamilton. With Federalists weak and out of power, Hamilton supported Burr’s opponent because he despised Burr. During the campaign, Hamilton criticized Burr, calling him “a dangerous man” who should “not be trusted with the reins of government.” His honor offended, Burr challenged Hamilton to a duel. Under the code duello, duels were an elaborate game of chicken in which one party forced the other to back down. Hamilton knew Burr could not be trusted, but he agreed to the duel anyway. They met in New Jersey, on the heights above the Hudson River. Using Hamilton’s pistols the dueled. As they turned to face one another, they fired—Hamilton firing into the air, as was the custom. Burr fired, hitting Hamilton in the side and grazing his heart. Mortally wounded, Hamilton died the next day. Now a wanted man, Burr fled to the Louisiana Territory. Burr’s plot: In 1807, Aaron Burr hatched an unlikely plot to establish his own empire in the West. The plot failed and Jefferson had Burr charged with treason. John Marshall, Jefferson’s nemesis, presided over the trial. The Constitution requires that to convict for treason there must be two witnesses; since the Jeffersonians had but one, Marshall advised the jury to acquit. Thus, Marshall established the narrowest definition of treason. Additionally, during the trial, the defense subpoenaed the President to testify. Jefferson refused, asserting executive privilege. This set a long-held precedent that the Executive is independent of the other branches. Impressment: One of the main issues regarding Britain's refusal to accept the neutrality of the U.S. in the Napoleonic Wars and one of the main causes of the War of 1812. It had long been the custom of Britain to raid British and colonial port towns and impress (press into service) men and force them to join the Royal Navy. In the early 1800s, Britain stopped American merchant vessels and kidnapped American sailors. Hostility against Britain grew significantly—especially in the summer of 1807 when a British ship, Leopard, fired upon an American ship, Chesapeake. The Chesapeake Affair led to cries for war and revenge from many Americans, but Jefferson refused. Embargo Act of 1807: With Britain and France both pressing in on American trade with Napoleon’s Berlin and Milan Decrees and with the Chesapeake Affair, Jefferson sought an answer in ending trade with both. The Embargo Act forbade all international trade to and from American ports. The Act backfired badly. Britain and France were unimpressed and American farmers, merchants, and sea traders (particularly in New England) protested vigorously. Many evaded the law. In March 1809, Congress thought better of the rule and announced that the more limited Non-Importation Act controlled in the situation allowing resumption of all trade except with Britain and France. Jefferson reluctantly accepted it. Tecumseh and the Battle of Tippecanoe (1811): Despite the Greenville Treaty, relations with the Indians in Ohio remained strained because of continued encroachment settlers on Indian land. By 1811, the Shawnee leader, Tecumseh, and this brother, The Prophet, determined to keep Indian hunting lands open. As Tecumseh traveled the South seeking support, Military Governor of the Indian Territory, William Henry Harrison, assembled troops at Tecumseh’s village on the Tippecanoe River. The Indians attacked a battle ensued. The Shawnee were defeated and retreated north to Canada. Westerners blamed Britain for the conflict, saying they had incited the Indians to violence. Tecumseh was killed during the War of 1812; Harrison, “Old Tippecanoe,” became POTUS in 1841. “No man in the nation desires peace more than I. But I prefer the troubled ocean of war, demanded by the honor and independence of the country, with all its calamities and desolations, to the tranquil, putrescent pool of ignominious peace.” Henry Clay “War Hawks”: Group of young Republicans from lower south and the west, elected in 1810, who demanded that America be respected overseas. They included: Henry Clay (KY), Felix Grundy (TN), John C. Calhoun (SC), and Andrew Jackson, among others. They insisted that Britain’s refusal to accept American neutrality and allow America’s free movement on the seas were worthy of war. They also hoped to gain new lands in Canada. They voted Clay in as Speaker of the House and Clay placed other War Hawks on important committees, almost completely controlling Congress. The War Hawks would not ignore the impressment issue or the Indian raids on the west, and using these issues they convinced President Madison to go to war. War of 1812 Sometimes called the “Second War of Independence” or “Mr. Madison’s War,” it was the war between the U.S. and Britain that grew out of tensions arising from America’s policy of neutrality in the Napoleonic Wars in Europe. Battles raged in the Great Lakes region, on the Thames River and in the Niagara Peninsula as U.S. invaded Canada, destroying the town of York (now Toronto). “It would be difficult to conceive a finer spectacle. The sky was brilliantly illumined by the different conflagrations, and a dark red light was thrown upon the road, sufficient to permit each man to view distinctly his comrade’s face.” -- British Soldier With Napoleon’s temporary defeat in 1814, Britain focused its efforts in America. British troops attacked Washington, DC, destroying the “President’s Palace.” The White House Important battles included Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry on Lake Erie (“We have met the enemy and they are ours”) and the attack at Fort McHenry at which Francis Scott Key wrote the “Star Spangled Banner.” “O say, can you see by the dawn’s early light, What so proudly we hailed at the twilight’s last gleaming, Whose broad stripes and bright stars through the perilous fight O’er the ramparts we watched so gallantly streaming? And the rockets red glare, the bomb bursting in air, Gave proof through the night that our flag was still there, O say does that star spangled banner yet waved O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave? Oh! Thus be it ever, when freemen shall stand Between their loved homes and the war’s desolation, Blest with vict’ry and peace, may the Heav’n-rescued land Praise the Power that hath made and preserved us a nation! Then conquer we must, when our cause it is just, And this be our motto: ‘In God is our trust” And the star-spangled banner in triumph shall wave O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave.” The war ended in December 1814 in the Treaty of Ghent, negotiated by John Quincy Adams, Henry Clay, and Albert Gallatin. It led to a long-standing peace with England, but before word of the treaty reached the U.S. a final battle occurred. The Battle of New Orleans was a rare American victory and it made Andrew Jackson a national hero. Jackson at the Battle of New Orleans “The Battle of New Orleans” In 1814 we took a little trip Along with Colonel Jackson down the mighty Mississip. We took a little bacon and we took a little beans And we caught the bloody British in the town of New Orleans. [Chorus:] We fired our guns and the British kept a'comin. There wasn't nigh as many as there was a while ago. We fired once more and they began to runnin' on Down the Mississippi to the Gulf of Mexico. We looked down the river and we see'd the British come. And there must have been a hundred of'em beatin' on the drum. They stepped so high and they made the bugles ring. We stood by our cotton bales and didn't say a thing. [Chorus] Old Hickory said we could take 'em by surprise If we didn't fire our muskets 'til we looked 'em in the eye We held our fire 'til we see'd their faces well. Then we opened up with squirrel guns and really gave 'em ... well [Chorus] [Bridge] They ran through the briars and they ran through the brambles And they ran through the bushes where a rabbit couldn't go. They ran so fast that the hounds couldn't catch 'em Down the Mississippi to the Gulf of Mexico.** We fired our cannon 'til the barrel melted down. So we grabbed an alligator and we fought another round. We filled his head with cannon balls, and powdered his behind And when we touched the powder off, the gator lost his mind. [Chorus] [Repeat Bridge] Hut Two Three Four Keep it up Tow Three Four Hartford Convention: December 1814 meeting of New England Federalists opposed to the War of 1812. Now the Federalists claimed a power to nullify federal laws and suggested the possibility of secession. The convention offered several Constitutional amendments, notably: abolishing the three-fifths compromise (not counting the slaves at all); requiring a two-thirds vote to declare war, prohibiting foreign-born citizens from holding any government office; limiting a person to one term as POTUS; and forbidding successive presidents from the same state. None of them passed. After the Battle of New Orleans a new nationalist fervor developed and made the Hartford conventioneers look unpatriotic. The Federalist Party died out within a year of the end of the war. Era of Good Feelings: The end of the War of 1812 ushered in a spirit of nationalism in America. The Federalist party disappeared, leaving a one-party nation. James Monroe won about 85% of the Electoral College vote for POTUS in 1816 and 99.6% of the EC vote in 1820. Two important military consequences resulted. (1) The U.S. became determined never to be invaded again; so it built forts along the Gulf of Mexico and Atlantic coasts to defend the nation and developed a policy of preemption—attack a threatening power, before it attacked us. The policy helps explain America’s militarism in the 19th century. (2) It resulted in a longstanding peace with Britain. Britain was tired of fighting the U.S.; after the war it often sided with the U.S. in international disputes, including giving backing to the Monroe Doctrine.