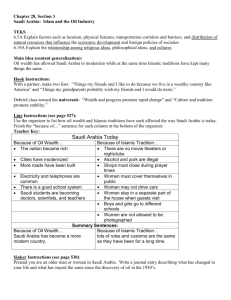

N. Rózsa Erzsébet, Ph.D. Deésy Veronika

advertisement