il 4 di aprile 2014

advertisement

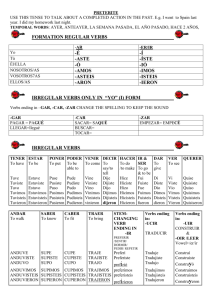

Italiano III Ora III e Ora IV il 22 di aprile 2011 4 META Unita´ Un Progetto del Passato Prossimo Un Progetto del Passato Prossimo Cio’ che hai fatto durante la vacanza Scritto Scrivete dieci frasi Cinque frasi Dove sei andato-a? Cinque frasi Cio´ che hai fatto durante la vacanza... Un disegno per ogni frase ORALE A parlare in Italiano di solito! Le Cinque Terre E Cultura parte II Le Cinque terre Cinque Terre Jump to: navigation, search The Cinque Terre (Italian pronunciation: [ˌtʃinkwe ˈtɛrːe]) is a rugged portion of coast on the Italian Riviera. It is in the the city of La Spezia. Liguria region of Italy, to the west of "The Five Lands" comprises five villages: Monterosso al Mare, Vernazza, Corniglia, Manarola, and Riomaggiore. The coastline, the five villages, and the surrounding hillsides are all part of the Cinque Terre National Park and is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Over the centuries, people have carefully built terraces on the rugged, steep landscape right up to the cliffs that overlook the sea. Part of its charm is the lack of visible corporate development. Paths, trains and boats connect the villages, and cars cannot reach them from the outside. The Cinque Terre area is a very popular tourist destination. The villages of the Cinque Terre were severely affected by torrential rains which caused floods and mudslides on October 25, 2011. Nine people were confirmed killed by the floods, and damage to the villages, particularly Vernazza and Monterosso al Mare, was extensive.[1] [hide] History The first historical documents on the Cinque Terre date back to the 11th century. Monterosso and Vernazza sprang up first, whilst the other villages grew later, under military and political supremacy of Genoa. In the 16th century to oppose the attacks by the Turks, the inhabitants reinforced the old forts and built new defence towers. From the year 600, the Cinque Terre experienced a decline which reversed only in the 14th century, thanks to the construction of the Military Arsenal of La Spezia and to the building of the railway line between Genoa and La Spezia. The railway allowed the inhabitants to escape their isolation, but also brought about abandonment of traditional activities. The consequence was an increase in poverty which pushed many to emigrate abroad, at least up to the 1970s, when the development of tourism brought back wealth. The variation of house colors is due to the fact that while fishermen were doing their jobs just offshore, they wanted to be able to see their house easily. This way, they could make sure their wives were still home doing the house work. Most of the families in the five villages made money by catching the fish and selling them in the small port villages. Fish was also their main source of food. Transportation and tourism There are few roads into the Cinque Terre towns that are Vernazza accessible by car, and the one into in particular is now open (June 2012 - but very narrow at many repair spots) to a parking area leading to a 1/2 mile walk to town after the October 2011 storm damage. It is best to plan not to travel by car at all but to park at La Spezia, for instance, and take the trains. Genova and the rest of the Local trains from La Spezia to region's network connect the "five lands". Intercity trains also connect the Cinque Terre to Milan, Rome, Turin and Tuscany. The tracks run most of the distance in tunnels between Riomaggiore and Monterosso. A passenger ferry runs between the five villages, except Corniglia. The ferry enters Cinque Terre from Genova's Old Harbour and La Spezia, Lerici, or Porto Venere. A walking trail, known as Sentiero Azzurro ("Light Blue Trail"), connects the five villages. The trail from Riomaggiore to Manarola is called the Via Dell'Amore ("Love Walk") and is wheelchair-friendly. The stretch from Manarola to Corniglia (still closed in June 2012 for ongoing repairs since the October 2011 damage)[2] is the easiest to hike, although the main trail into Corniglia finishes with a climb of 368 steps. Food This section entitled Food and Wine needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (March 2010) Liguria Given its location on the Mediterranean, seafood is plentiful in the local cuisine. Anchovies of Monterosso are a local specialty designated with a Protected Designation of Origin status from the The mountainsides of the Cinque Terre are heavily terraced and are used to cultivate grapes and olives. This area, and the region of Liguria, as a whole, is known for pesto — a sauce made from basil leaves, garlic, European Union. salt, olive oil, pine nuts and pecorino cheese. Focaccia is a particularly common locally baked bread product. Farinata is also a typical snack found in bakeries and pizzerias- essentially it is a savoury and crunchy pancake made from a base of chick-pea "miele di Corniglia," gelato, made from local honey. flour. The town of Corniglia is particularly popular for The grapes of the Cinque Terre are used to produce two locally made wines. The eponymous Cinque Terre and the Sciachetrà are both made using Bosco, Albarola, and Vermentino grapes. Both wines are produced by the Cooperative Agricoltura di Cinque Terre (“Cinque Terre Agricultural Cooperative”), located between Manarola and Volastra. Other DOC producers are Forlini-Capellini, Walter de Batté, Buranco, Arrigoni. In addition to wines, other popular local drinks include grappa, a brandy made with the pomace left from winemaking, and limoncello, a sweet liqueur flavored with lemons. Preservation In 1998, the Italian Ministry for the Environment set up the Protected natural marine area Cinque Terre to protect the natural environment and to promote socio-economical development compatible with the natural landscape of the area.[4] In 1999 the Parco Nazionale delle Cinque Terre was set up to conserve the ecological balance, protect the landscape, and safeguard the anthropological values of the location.[5] Nevertheless, the dwindling interest in cultivation and maintenance of the terrace walls posed a long-term threat to the site, which was for this reason included in the 2000 and 2002 World Monuments Watch by the World Monuments Fund.[6] The organization secured grants from American Express to support a study of the conservation of Cinque Terre. Following the study, a site management plan was created. Other towns near the Cinque Terre Bonassola La Spezia Lerici Levanto Porto Venere Sarzana Volastra Cinque Terre Monterosso al Mare Vernazza Corniglia Manarola Riomaggiore SIENA Siena (Italian pronunciation: [ˈsjɛːna] ( listen); in English sometimes spelled Sienna) is a city in Tuscany, Italy. It is the capital of the province of Siena. The historic centre of Siena has been declared by UNESCO a World Heritage Site. It is one of the nation's most visited tourist attractions, with over 163,000 international arrivals in 2008.] Siena is famous for its cuisine, art, museums, medieval cityscape and the Palio, a horse race held twice a year. History Siena, like other Tuscan hill towns, was first settled in the time of the Etruscans (c. 900– 400 BC) when it was inhabited by a tribe called the Saina. The Etruscans were an advanced people who changed the face of central Italy through their use of irrigation to reclaim previously unfarmable land, and their custom of building their settlements in well-defended hill forts. A Roman town called Saena Julia was founded at the site in the time of the Emperor Augustus. The first document mentioning it dates from AD 70. Some archaeologists assert that Siena was controlled for a period by a Gaulish tribe called the Senones. The Roman origin accounts for the town's emblem: a she-wolf suckling infants Romulus and Remus. According to legend, Siena was founded by Senius, son of Remus, who was in turn the brother of Romulus, after whom Rome was named. Statues and other artwork depicting a shewolf suckling the young twins Romulus and Remus can be seen all over the city of Siena. Other etymologies derive the name from the Etruscan family name "Saina," the Roman family name of the "Saenii," or the Latin word "senex" ("old") or the derived form "seneo", "to be old". Siena did not prosper under Roman rule. It was not sited near any major roads and lacked opportunities for trade. Its insular status meant that Christianity did not penetrate until the 4th century AD, and it was not until the Lombards invaded Siena and the surrounding territory that it knew prosperity. After the Lombard occupation, the old Roman roads of Via Aurelia and the Via Cassia passed through areas exposed to Byzantine raids, so the Lombards rerouted much of their trade between the Lombards' northern possessions and Rome along a more secure road through Siena. Siena prospered as a trading post, and the constant streams of pilgrims passing to and from Rome provided a valuable source of income in the centuries to come. The oldest aristocratic families in Siena date their line to the Lombards' surrender in 774 to Charlemagne. At this point, the city was inundated with a swarm of Frankish overseers who married into the existing Sienese nobility and left a legacy that can be seen in the abbeys they founded throughout Sienese territory. Feudal power waned however, and by the death of Countess Matilda in 1115 the border territory of the Mark of Tuscia which had been under the control of her family, the Canossa, broke up into several autonomous regions. This ultimately resulted into the creation of the Republic of Siena. It existed for over four hundred years, from the late 11th century until the year 1555. In the Italian War of 1551– 1559, the republic was defeated by the rival Duchy of Florence in alliance with the Spanish crown. After 18 months of resistance, Siena surrendered to Spain on 17 April 1555, marking the end of the republic. The new Spanish King Philip, owing huge sums to the Medici, ceded it (apart a series of coastal fortress annexed to the State of Presidi) to the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, to which it belonged until the unification of Italy in the 19th century. A Republican government of 700 Sienese families in Montalcino resisted until 1559. The picturesque city remains an important cultural centre, especially for humanist disciplines. Siena Cathedral Interior of the Siena Cathedral. Façade of the Palazzo Pubblico (town hall) during the Palio days. Piazza Salimbeni. Streets of old Siena. Church of San Domenico. View from the Campanile del Mangia. The Siena Cathedral (Duomo), begun in the 12th century, is one of the great examples of Italian Romanesque-Gothic architecture. Its main façade was completed in 1380. It is unusual for a cathedral in that its axis runs north-south. This is because it was originally intended to be the largest cathedral in the world, with a north-south transept and an east-west nave. After the completion of the transept and the building of the east wall (which still exists and may be climbed by the public via an internal staircase) the money ran out and the rest of the cathedral was abandoned. Inside is the famous Gothic octagonal pulpit by Nicola Pisano (1266–1268) supported on lions, and the labyrinth inlaid in the flooring, traversed by penitents on their knees. Within the Sacristy are some perfectly preserved renaissance frescos by Domenico Ghirlandaio, and, beneath the Duomo, in the baptistry is the baptismal font with bas-reliefs by Donatello, Lorenzo Ghiberti, Jacopo della Quercia and other 15th-century sculptors. The Museo dell'Opera del Duomo contains Duccio's famous Maestà (1308–1311) and various other works by Sienese masters. More Sienese paintings are to be found in the Pinacoteca, e.g. 13th-century works by Diotisalvi di Speme. The shell-shaped Piazza del Campo, the town square, which houses the Palazzo Pubblico and the Torre del Mangia, is another architectural treasure, and is famous for hosting the Palio horse race. The Palazzo Pubblico, itself a great work of architecture, houses yet another important art museum. Included within the museum is Ambrogio Lorenzetti's series of frescos on the good government and the results of good and bad government and also some of the finest frescoes of Simone Martini and Pietro Lorenzetti. On the Piazza Salimbeni is the Palazzo Salimbeni, a notable building and also the medieval headquarters of Monte dei Paschi di Siena, one of the oldest banks in continuous existence and a major player in the Sienese economy. Housed in the notable Gothic Palazzo Chigi on Via di Città is the Accademia Musicale Chigiana, Siena's conservatory of music. Other churches in the city include: Basilica dell'Osservanza Santa Maria dei Servi San Domenico San Francesco Santo Spirito San Martino Sanctuary of Santa Caterina, incorporating the old house of St. Catherine of Siena. It houses the miraculous Crucifix (late 12th century) from which the saint received her stigmata, and a 15th-century statue of St. Catherine. The city's gardens include the Orto Botanico dell'Università di Siena, a botanical garden maintained by the University of Siena. The Medicean Fortress houses the Enoteca Italiana and the Siena Jazz School, with courses and concerts all the year long and a major festival during the International Siena Jazz Masterclasses. Over two weeks more than 30 concerts and jam sessions are held in the two major town squares, on the terrace in front of the Enoteca, in the gardens of the Contrade clubs, and in numerous historical towns and villages of the Siena province. Siena is also home of Sessione Senese per la Musica e l'Arte (SSMA), a summer music program for musicians, is a fun/learning musical summer experience. In the neighbourhood are numerous patrician villa, numerous of which attributed to Baldassarre Peruzzi: Villa Chigi Castle of Belcaro Villa Celsa Villa Cetinale Villa Volte Alte Contrade Siena retains a ward-centric culture from medieval times. Each ward (contrada) is represented by an animal or mascot, and has its own boundary and distinct identity. Ward rivalries are most rampant during the annual horse race (Palio) in the Piazza del Campo. The Palio The Palio di Siena is a traditional medieval horse race run around the Piazza del Campo twice each year, on 2 July and 16 August. The event is attended by large crowds, and is widely televised. Seventeen Contrade (which are city neighbourhoods originally formed as battalions for the city's defence) vie for the trophy: a painted banner, or Palio bearing an image of the Blessed Virgin Mary. For each race a new Palio is commissioned by well-known artists and Palios won over many years can often be seen in the local Contrade museum. During each Palio period, the city is decked out in lamps and flags bearing the Contrade colours. Ten of the seventeen Contrade run in each Palio: seven run by right (having not run in the previous year's corresponding Palio) together with three drawn by lot from the remaining ten. A horse is assigned to each by lot and is then guarded and cared for in the Contrade stable. The jockeys are paid huge sums and indeed there are often deals and bribes between jockeys or between "allied" Contrade committees to hinder other riders, especially those of 'enemy' Contrade. For the three days preceding the Palio itself, there are practice races. The horses are led from their stables through the city streets to the Campo, accompanied by crowds wearing Contrade scarves or tee-shirts and the air is filled with much singing and shouting. Though often a brutal and dangerous competition for horse and bare-back rider alike, the city thrives on the pride this competition brings. The Palio is not simply a tourist event as a true Sienese regards this in an almost tribal way, with passions and rivalry similar to that found at a football 'Derby' match In fact the Sienese are baptised twice, once in church and a second time in their own Contrade fountain. This loyalty is maintained through a Contrade 'social club' and regular events and charitable works. Indeed the night before the Palio the city is a mass of closed roads as each Contrade organises its own outdoor banquet, often for numbers in excess of 1,000 diners. On the day of the Palio itself the horses are accompanied by a spectacular display of drummers and flag twirlers dressed in traditional medieval costumes who first lead the horse and jockey to the Contrade parish church and then join a procession around the Piazza del Campo square This traditional parade is called the Corteo Storico, which begins in the streets and concludes in the Piazza del Campo encircling the square. There are often long delays while the race marshall attempts to line up the horses, but once underway the Campo becomes a cauldron of wild emotion for the 3 minutes of the race. This event is not without its controversy however, and recently, there have been complaints about the treatment of the horses and to the danger run by the riders. To better protect the horses, steps have been taken to make veterinary care more easily available during the main race. Also at the most dangerous corners of the course, cushions are used to help protect both the riders and horses. Art Madonna and Child with saints polyptych by Duccio (1311–1318). Sassetta, Institution of the Eucharist (14301432), Pinacoteca di Siena. Over the centuries, Siena has had a rich tradition of arts and artists. The list of artists from the Sienese School include Duccio and his student Simone Martini, Pietro Lorenzetti and Martino di Bartolomeo. A number of well known works of Renaissance and High Renaissance art still remain in galleries or churches in Siena. The Church of San Domenico contains art by Guido da Siena, dating to mid-13th century. Duccio's Maestà which was commissioned by the City of Siena in 1308 was instrumental in leading Italian painting away from the hieratic representations of Byzantine art and directing it towards more direct presentations of reality. And his Madonna and Child with Saints polyptych, painted between 1311 and 1318 remains at the city's Pinacoteca Nazionale. The Pinacoteca also includes several works by Domenico Beccafumi, as well as art by Lorenzo Lotto, Domenico di Bartolo and Fra Bartolomeo. Fashion Siena has grown in importance because of its easy access to locally produced luxury goods in Tuscany and with new independent fashion designers such as Romana Correale. Economy The main activities are tourism, services, agriculture, handicrafts and light industry. Agriculture Agriculture constitutes Siena's primary industry. As of 2009, Siena's agricultural workforce comprises 919 companies with a total area of 10,755 km2 for a UAA (usable agricultural area) . Industry and manufacturing The industrial sector of the Sienese economy is not very developed. However, The confectionery industry is one of the most important of the traditional sectors of the secondary industry, because of the many local specialties. Among the best known are Panforte, a precursor to modern fruitcake, Ricciarelli biscuits, made out of almond paste, and the well-known gingerbread, and thehorses. Also renowned is "Noto" a sweet made of honey, almonds and pepper. The area known for making these delicacies ranges between Tuscany and Umbria. Other seasonal specialties are the chestnut and the pan de 'Santi (or Pan co' Santi) traditionally prepared in the weeks preceding the Festival of Saints, the November 1. All are marketed both industrial and artisan bakeries in different cities. The area has also seen a growth in biotechnology. Centenary Institute Sieroterapico Achille Sclavo, is now Swissowned and operates under the company name, Novartis Vaccines. Novartis develops and produces vaccines and employs about a thousand people. fin Helping verbs PASSATO PROSSIMO Past Participles and the two helping verbs: AVERE and ESSERE!!!!! For most italian verbs and all transitive verbs (verbs that take a direct object), the passato prossimo is conjugated with the present of the auxiliary verb avere+the past participle (participio passato) of the main verb. The participio passato of the regular verbs is formed by replacing the infinitive ending –are, -ere, and –ire with –ato, -uto, and –ito, respectively. With avere Comprare comprato Ricevere ricevuto Dormire dormito Irregular past participles are below: with avere Fare fatto Bere bevuto Chiedere chiesto Chiudere chiuso Conoscere conosciuto Leggere letto Mettere messo Perdere perduto (perso) Prendere preso Rispondere risposto Scrivere scritto Spendere speso Vedere veduto (visto) Aprire aperto Dire detto Offrire offerto Most intransitive verbs (verbs that do not take a direct object) are conjugated with the auxiliary essere. In this case, the past participle must agree with the subject in gender and number. Andare Andato Venire Venuto Arrivare Arrivato Partire Partito Ritornare Ritornato Entrare Entrato Uscire Uscito Salire Salito Discendere Disceso Cadere Caduto Nascere Nato Morire Morto Essere Stato Stare Stato Restare Restato Diventare Diventato passato prossimo The — grammatically referred to as the present perfect—is a compound tense (tempo composto) that expresses a fact or action that happened in the recent past or that occurred long ago but still has ties to the present. Here are a few examples of how the passato prossimo appears in Italian: Ho appena chiamato. (I just called.) Mi sono iscritto all'università quattro anni fa. (I entered the university four years ago.) Questa mattina sono uscito presto. (This morning I left early.) Il Petrarca ha scritto sonetti immortali. (Petrarca wrote enduring sonnets.) The following table lists some adverbial expressions that are often used with the passato prossimo: COMMON ADVERBIAL EXPRESSIONS OFTEN USED WITH THE PASSATO PROSSIMO ieri yesterday ieri pomeriggio yesterday afternoon ieri sera last night il mese scorso last month l'altro giorno the other day stamani this morning tre giorni fa three days ago The present perfect tense is used in the following situations: an action which took place a short time ago. an action which took place some time ago and the results of the action can still be felt in the present an experience in your life an action which has finished but the time period (e.g. this year , this week, today) hasn't finished yet The present perfect is formed in the following way: il presente indicativo dei verbi essere o avere Auxiliary to have/ to be + in the present form il participio passato del verbo in questione Past participle Passato Prossimo: Past Tense in Italian Here is a form of a past tense in Italian, passato prossimo, which is used for events that happened once. Learn the formation of the Italian passato prossimo for both regular and irregular verbs. Also learn when essere or avere should be used. Regular Verb Formation of the Past Participle Passato prossimo follows a simple pattern: essere or avere and the past particle. When we use passato prossimo, we talk about something that has happened once, instead of an ongoing event in the past (we use imperfect then). For example: Ieri ho mangiato un panino. (Yesterday I ate a sandwich) Notice the verb formation in the sentence: the first verb is avere in the present indicative form, followed by the past participle for the verb mangiare, which means to eat. -the formation of the past participle with regular verbs — remember three verb endings exist in regular Italian verbs: are, -ere and -ire. When we form the past participle, we remove the verb ending to get the stem, then add the past participle ending. For example: -are verbs: the ending for the past participle is -ato cantare → cantato (to sing) -ere verbs: the ending for the past participle is -uto credere → creduto (to believe) -ire verbs: the ending for the past participle is -ito dormire → dormito (to sleep) Irregular Verb Formation of the Past Participle Verbs that are irregular in Italian do not follow the same pattern as the regular verbs for the past participle. There is no particular pattern. some of the common verbs: accendere → acceso (to turn on) aprire → aperto (to open) bere → bevuto (to drink) chiedere → chiesto (to ask) chiudere → chiuso (to close) correggere → corretto (to correct) correre → corso (to run) cuocere → cotto (to cook) decidere → deciso (to decide) dire → detto (to say/tell) dividere → diviso (to divide) essere → stato (to be) fare → fatto (to do/make) leggere → letto (to read) mettere → messo (to put) morire → morto (to die) muovere → mosso (to move) nascere → nato (to be born) nascondere → nascosto (to hide) offrire → offerto (to offer) perdere → perso or perduto (to lose) piacere → piaciuto (to like) piangere → pianto (to cry) porre → posto (to place) prendere → preso (to take) ridere → riso (to laugh) rimanere → rimasto (to stay) risolvere → risolto (to solve) rispondere → risposto (to answer) rompere → rotto (to break) scegliere → scelto (to choose) scrivere → scritto (to write) succedere → successo (to happen) togliere → tolto (to remove) tradurre → tradotto (to translate) uccidere → ucciso (to kill) vedere → visto or veduto (to see) venire → venuto (to come) vincere → vinto (to win) vivere → vissuto (to live) THE HELPING VERB: Essere or Avere? In Italian passato prossimo, we have two auxiliary verbs: essere and avere. Essere is used when we have: → Intransitive verbs (verbs with no direct object) → Movement verbs (examples are andare (to go), arrivare (to arrive) and tornare (to return)) → State verbs (examples are stare (to be) and rimanere (to stay)) → Changing state verbs (examples are diventare (to become), nascere (to be born) and morire (to die) → Reflexive verbs (verbs preceded by a pronoun, such as mi) → Other verbs: accadere/succedere (to happen), bastare (to be enough/need), costare (to cost), dipendere (to depend), dispiacere (to displease/mind), mancare (to miss), occorrere (to be necessary), parere (to seem/think), piacere (to like), sembrare (to seem) and toccare (touch). When we use essere as the auxiliary verb, the past participle matches in gender and quantity. Avere is used when we have: → Transitive verbs (verbs followed by a direct object) Certain verbs can use either essere or avere — it depends on whether we use the verb intransitively or transitively. Let's go over those verbs: aumentare (to increase) bruciare (to burn) cambiare (to change) continuare (to continue) diminuire (to reduce/decrease) passare (to go past) salire (to go up/get on) saltare (to jump) scendere (to go down/get off) Another way of understanding which auxiliary verb (helping verb) to use: Essere or Avere? In Italian passato prossimo, we have two auxiliary verbs: essere and avere. Let's go over the different rules for which auxiliary verb to use: Essere is used when we have: → Intransitive verbs (verbs with no direct object) → Movement verbs (examples are andare (to go), arrivare (to arrive) and tornare (to return)) → State verbs (examples are stare (to be) and rimanere (to stay)) → Changing state verbs (examples are diventare (to become), nascere (to be born) and morire (to die) → Reflexive verbs (verbs preceded by a pronoun, such as mi) → Other verbs: accadere/succedere (to happen), bastare (to be enough/need), costare (to cost), dipendere (to depend), dispiacere (to displease/mind), mancare (to miss), occorrere (to be necessary), parere (to seem/think), piacere (to like), sembrare (to seem) and toccare (touch). When we use essere as the auxiliary verb, the past participle matches in gender and quantity. Avere is used when we have: → Transitive verbs (verbs followed by a direct object) Certain verbs can use either essere or avere — it depends on whether we use the verb intransitively or transitively. Let's go over those verbs: aumentare (to increase) bruciare (to burn) cambiare (to change) continuare (to continue) diminuire (to reduce/decrease) passare (to go past) salire (to go up/get on) scendere (to go down/get off) SuperCiao 1B La Bici - parts of a bike 1. A continuare con Inno nazionali di Italia .... SuperCiao IB Tutti devono cantare 2. Inno del popolo di Veneto 3. Cultura degli stati Italiani e la storia del RISORGIMENTO Capitolo 3 L´ introduzione Tutti cantano Fratelli d'Italia Italian unification History of Italy Italian unification (Italian: Risorgimento [risordʒiˈmento], meaning the Resurgence) was the political and social movement that agglomerated different states of the Italian peninsula into the single state of the Kingdom of Italy in the 19th century. Despite a lack of consensus on the exact dates for the beginning and end of this period, many scholars agree that the process began in 1815 with the Congress of Vienna and the end of Napoleonic rule, and ended in 1870 with the Capture of Rome. Some of the terre irredente did not, however, join the Kingdom of Italy until after World War I with the Treaty of SaintGermain. Some nationalists see the Armistice of Villa Giusti as the end of unification.[3] Fratelli d'Italia L'Italia s'è desta, Dell'elmo di Scipio S'è cinta la testa. Dov'è la Vittoria? Le porga la chioma, Ché schiava di Roma Iddio la creò. Stringiamci a coorte Siam pronti alla morte L'Italia chiamò. Noi siamo da secoli Calpesti, derisi, Perché non siam popolo, Perché siam divisi. Raccolgaci un'unica Bandiera, una speme: Di fonderci insieme Già l'ora suonò. Stringiamci a coorte Siam pronti alla morte L'Italia chiamò. Uniamoci, amiamoci, l'Unione, e l'amore Rivelano ai Popoli Le vie del Signore; Giuriamo far libero Il suolo natìo: Uniti per Dio Chi vincer ci può? Stringiamci a coorte Siam pronti alla morte L'Italia chiamò. Dall'Alpi a Sicilia Dovunque è Legnano, Ogn'uom di Ferruccio Ha il core, ha la mano, I bimbi d'Italia Si chiaman Balilla, Il suon d'ogni squilla I Vespri suonò. Stringiamci a coorte Siam pronti alla morte L'Italia chiamò. Son giunchi che piegano Le spade vendute: Già l'Aquila d'Austria Le penne ha perdute. Il sangue d'Italia, Il sangue Polacco, Bevé, col cosacco, Ma il cor le bruciò. Stringiamci a coorte Siam pronti alla morte L'Italia chiamò La Vittoria si offre alla nuova Italia e a Roma, di cui la dea fu schiava per volere divino. La Patria chiama alle armi: la coorte, infatti, era la decima parte della legione romana Mazziniano e repubblicano, Mameli traduce qui il disegno politico del creatore della Giovine Italia e della Giovine Europa. "Per Dio" è un francesismo, che vale come "attraverso Dio", "da Dio" Sebbene non accertata storicamente, la figura di Balilla rappresenta il simbolo della rivolta popolare di Genova contro la coalizione austropiemontese. Dopo cinque giorni di lotta, il 10 dicembre 1746 la città è finalmente libera dalle truppe austriache che l'avevano occupata e vessata per diversi mesi L'Austria era in declino (le spade vendute sono le truppe mercenarie, deboli come giunchi) e Mameli lo sottolinea fortemente: questa strofa, COMPITI COMPITI Il Passato Prossimo! SuperCiao 1B I QUADERNI NOTEBOOKS collected today !!! il 4 di aprile 2014 I COMPITI Studiate il passato prossimo!! IN BOCCA AL LUPO! IN BOCCA AL LUPO! IN BOCCA AL LUPO! IN BOCCA AL LUPO! IN BOCCA AL LUPO! IN BOCCA AL LUPO!