Free Will and Determinism

advertisement

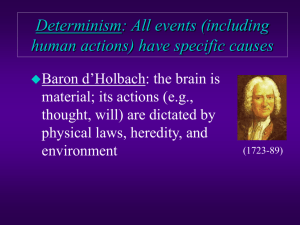

Dialogue Education 2009 Have I got any choice? Free Will versus Determinism THIS CD HAS BEEN PRODUCED FOR TEACHERS TO USE IN THE CLASSROOM. IT IS A CONDITION OF THE USE OF1THIS CD THAT IT BE USED ONLY BY THE PEOPLE FROM SCHOOLS THAT HAVE PURCHASED THE CD ROM FROM DIALOGUE EDUCATION. (THIS DOES NOT PROHIBIT ITS USE ON A SCHOOL’S INTRANET) • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Contents Page 3 – Hoop shoot game on Free Will Page 4 - Video Presentation outlining the Free Will/Determinism debate Pages 5 to 6 - Free Will Page 7 - Fundamental questions in the debate Page 8 - Determinism Page 10 - Libertarianism Pages 11 to 12 - Compatibilism Page 13 - Incompatibilism Page 14 - Overview map Pages15 to 17 - Moral Responsibility Pages 18 to 22 - Science and the Free Will debate Pages 24 to 25 - Eastern Philosophy Page 26 - Jewish Philosophy Page 27 - Islamic Philosophy Pages 28 to 29 - Christian philosophy Page 31 - Community of Inquiry Stimulus Material Page 32 - Bibliography 2 HOOPSHOOT • Click on the image above for a game of “HOOPSHOOT”. Try playing the game with your students at the start and the end of the unit. Make sure you have started the slide show and are connected to the internet. 3 You Tube Presentation on Free Will / Determinism debate • Click on the image to the left. You will need to be connected to the internet to view this presentation. • Enlarge to full 4 screen Free Will versus Determinism The question of free will is whether, and in what sense, rational agents exercise control over their actions and decisions. Addressing this question requires understanding the relationship between freedom and cause, and determining whether the laws of nature are causally deterministic. The various philosophical positions taken differ on whether all events are determined or not — determinism versus indeterminism — and also on whether freedom can coexist with determinism or not — compatibilism versus incompatibilism. So, for instance, 'hard determinists' argue that the universe is deterministic, and that this makes free will impossible. 5 Free Will versus Determinism • The principle of free will has religious, ethical, and scientific implications. For example, in the religious realm, free will may imply that an omnipotent divinity does not assert its power over individual will and choices. In ethics, it may imply that individuals can be held morally accountable for their actions. In the scientific realm, it may imply that the actions of the body, including the brain and the mind, are not wholly determined by physical causality. The question of free will has been a central issue since the beginning of philosophical thought. 6 Free Will vs Determinism The basic philosophical positions on the problem of free will can be divided in accordance with the answers they provide to two questions: 1. Is determinism true? 2. Does free will exist? Determinism is roughly defined as the view that all current and future events are causally necessitated by past events combined with the laws of nature. Neither determinism nor its opposite, non-determinism, are positions in the debate about free will. Compatibilism is the view that the existence of free will and the truth of determinism are compatible with each other; this is opposed to incompatibilism which is the view that there is no way to reconcile a belief in a deterministic universe with a belief in free will. Hard determinism is the version of incompatibilism that accepts the truth of determinism and rejects the idea that humans have any free will. Metaphysical libertarianism topically agrees with hard determinism only in rejecting compatibilism. Because libertarians accept the existence of free will, they must reject determinism and argue for some version of indeterminism that is compatible with freedom. 7 Determinism 8 Determinism Determinism is a broad term with a variety of meanings. Corresponding to each of these different meanings, there arises a different problem of free will. Causal (or nomological) determinism is the thesis that future events are necessitated by past and present events combined with the laws of nature. Such determinism is sometimes illustrated by the thought experiment of Laplace's demon. Imagine an entity that knows all facts about the past and the present, and knows all natural laws that govern the universe. Such an entity may be able to use this knowledge to foresee the future, down to the smallest detail. Logical determinism is the notion that all propositions, whether about the past, present or future, are either true or false. The problem of free will, in this context, is the problem of how choices can be free, given that what one does in the future is already determined as true or false in the present. Theological determinism is the thesis that there is a God who determines all that humans will do, either by knowing their actions in advance, via some form of omniscience or by decreeing their actions in advance.The problem of free will, in this context, is the problem of how our actions can be free, if there is a being who has determined them for us ahead of time. Biological determinism is the idea that all behavior, belief, and desire are fixed by our genetic endowment. There are other theses on determinism, including cultural determinism and psychological determinism. Combinations and syntheses of determinist theses, e.g. bioenvironmental determinism, are even more common. 9 Libertarianism Libertarianism is the view that humans have free will , and that we have the freedom to choose what we want, and that our choices are not pre-determined. It allows the existence of the concepts of “good” and “evil” because people have the capacity to do either of those with the ability to have chosen the alternative. Many religious people are Libertarianists and some use the existence of free will as proof of a divine creator. 10 Compatibilism Compatibilists maintain that determinism is compatible with free will. A common strategy employed by "classical compatibilists", such as Thomas Hobbes, is to claim that a person acts freely only when the person willed the act and the person could have done otherwise, if the person had decided to. Hobbes sometimes attributes such compatibilist freedom to the person and not to some abstract notion of will, asserting, for example, that "no liberty can be inferred to the will, desire, or inclination, but the liberty of the man; which consisteth in this, that he finds no stop, in doing what he has the will, desire, or inclination to doe." In articulating this crucial proviso, David Hume writes, "this hypothetical liberty is universally allowed to belong to every one who is not a prisoner and in chains". To illustrate their position, compatibilists point to clear-cut cases of someone's free will being denied, through rape, murder, theft, or other forms of constraint. In these cases, free will is lacking not because the past is causally determining the future, but because the aggressor is overriding the victim's desires and preferences about his own actions. The aggressor is coercing the victim and, according to compatibilists, this is what overrides free will. Thus, they argue that determinism does not matter; what matters is that individuals' choices are the results of their own desires and preferences, and are not overridden by some external (or internal) force. To be a compatibilist, one need not endorse any particular conception of free will, but only deny that determinism is at odds with free will. 11 Compatibilism William James' views were ambivalent. While he believed in free will on "ethical grounds," he did not believe that there was evidence for it on scientific grounds, nor did his own introspections support it. Moreover, he did not accept incompatibilism as formulated below; he did not believe that the indeterminism of human actions was a prerequisite of moral responsibility. In his work Pragmatism, he wrote that "instinct and utility between them can safely be trusted to carry on the social business of punishment and praise" regardless of metaphysical theories. He did believe that indeterminism is important as a "doctrine of relief"—it allows for the view that, although the world may be in many respects a bad place, it may, through individuals' actions, become a better one. Determinism, he argued, undermines meliorism—the idea that progress is a real concept leading to improvement in the world. 12 Incompatibilism "Hard determinists", such as d'Holbach, are those incompatibilists who accept determinism and reject free will. "Metaphysical libertarians", such as Thomas Reid, Peter van Inwagen, and Robert Kane, are those incompatibilists who accept free will and deny determinism, holding the view that some form of indeterminism is true. Another view is that of hard incompatibilism which states that free will is incompatible with both determinism and indeterminism. This view is defended by Derk Pereboom. One of the traditional arguments for incompatibilism is based on an "intuition pump": if a person is determined in his or her choices of actions, then he or she must be like other mechanical things that are determined in their behaviour such as a wind-up toy, a billiard ball, a puppet, or a robot. Because these things have no free will, then people must have no free will, if determinism is true.This argument has been rejected by compatibilists such as Daniel Dennett on the grounds that, even if humans have something in common with these things, it does not follow that there are no important differences. “There is no mind absolute or Free will, but the mind is determined for willing this or that by a cause which is determined in its turn by another cause, and this one again by another, and so on to infinity.” (Spinoza, 1673) 13 A Diagram showing the Different stances in relation to Determinism and Free will 14 Moral responsibility • Society generally holds people responsible for their actions, and will say that they deserve praise or blame for what they do. However, many believe that moral responsibility requires free will. Thus, another important issue in the debate on free will is whether individuals are ever morally responsible for their actions—and, if so, in what sense. • Incompatibilists tend to think that determinism is at odds with moral responsibility. It seems impossible that one can hold someone responsible for an action that could be predicted from (potentially) the beginning of time. Hard determinists say "So much the worse for free will!" and discard the concept. Clarence Darrow, the famous defence attorney, pleaded the innocence of his clients, Leopold and Loeb, by invoking such a notion of hard determinism. During his summation, he declared: What has this boy to do with it? He was not his own father; he was not his own mother; he was not his own grandparents. All of this was handed to him. He did not surround himself with governesses and wealth. He did not make himself. And yet he is to be compelled to pay. 15 Moral responsibility Conversely, libertarians say "So much the worse for determinism!“ Daniel Dennett asks why anyone would care about whether someone had the property of responsibility and speculates that the idea of moral responsibility may be "a purely metaphysical hankering". Jean-Paul Sartre argues that people sometimes avoid incrimination and responsibility by hiding behind determinism: "... we are always ready to take refuge in a belief in determinism if this freedom weighs upon us or if we need an excuse". However, the position that classifying such people as "base" or "dishonest" makes no difference to whether or not their actions are determined is quite as tenable. • The issue of moral responsibility is at the heart of the dispute between hard determinists and compatibilists. Hard determinists are forced to accept that individuals often have "free will" in the compatibilist sense, but they deny that this sense of free will can ground moral responsibility. The fact that an agent's choices are unforced, hard determinists claim, does not change the fact that determinism robs the agent of responsibility. 16 Moral responsibility • • Compatibilists argue, on the contrary, that determinism is a prerequisite for moral responsibility. Society cannot hold someone responsible unless his actions were determined by something. This argument can be traced back to David Hume. If indeterminism is true, then those events that are not determined are random. It is doubtful that one can praise or blame someone for performing an action generated spontaneously by his nervous system. Instead, one needs to show how the action stemmed from the person's desires and preferences—the person's character—before one can hold the person morally responsible. Libertarians may reply that undetermined actions are not random at all, and that they result from a substantive will whose decisions are undetermined. This argument is considered unsatisfactory by compatibilists, for it just pushes the problem back a step. It also seems to involve some mysterious metaphysics, as well as the concept of ex nihilo nihil fit. Libertarians have responded by trying to clarify how undetermined will could be tied to robust agency. St. Paul, in his Epistle to the Romans addresses the question of moral responsibility as follows: "Hath not the potter power over the clay, of the same lump to make one vessel unto honour, and another unto dishonour?“ In this view, individuals can still be dishonoured for their acts even though those acts were ultimately completely determined by God. 17 Science… The most extreme determinists are mostly scientists, such as Richard Dawkins. One argument against determinism focuses on science and free will in relation to it, the basic argument is as follows: Science is purely deterministic due to the scientific method of analysis. But, just because science is deterministic, does not mean the universe is. Science is only capable of seeing the universe as deterministic, because it looks only at the effects that are caused by matter and energy. An analysis based on cause and effect can only conclude in determinism. In science a theory is only considered True if it has proof, which means you have to demonstrate that it works in an experiment. And the experiment has to produce the same outcome if it is carried out correctly. This means that the existence of Free will cannot be proven through scientific method. This is because, if Free will exists, it is possible to produce different outcomes in the same situation regardless of the events leading up to it. This means that it is impossible for the existence of free will to be proved True by science. Any experiment that is conducted by scientists to prove the existence of free will is invalid as proof because if the results vary, they could also or only be due to unknown factors. 18 Physics • • Early scientific thought often portrayed the universe as deterministic,[and some thinkers claimed that the simple process of gathering sufficient information would allow them to predict future events with perfect accuracy. Modern science, on the other hand, is a mixture of deterministic and stochastic theories.Quantum mechanics predicts events only in terms of probabilities, casting doubt on whether the universe is deterministic at all. Current physical theories can not resolve the question, whether determinism is true of the world, being very far from a potential Final Theory, and open to many different interpretations. Assuming that an indeterministic interpretation of quantum mechanics turns out to be the right one, one may still object that such indeterminism is confined to microscopic phenomena. However, many macroscopic phenomena are based on quantum effects, for instance, some hardware random number generators work by amplifying quantum effects into practically usable signals. A more significant question is whether the indeterminism of quantum mechanics allows for anything like free will, when the laws of quantum mechanics are supposed to give a complete probabilistic account of the motion of particles. 19 Genetics Like physicists, biologists have frequently addressed questions related to free will. One of the most heated debates in biology is that of "nature versus nurture", concerning the relative importance of genetics and biology as compared to culture and environment in human behavior. The view of most researchers is that many human behaviors can be explained in terms of humans' brains, genes, and evolutionary histories.This point of view raises the fear that such attribution makes it impossible to hold others responsible for their actions. Steven Pinker's view is that fear of determinism in the context of "genetics" and "evolution" is a mistake, that it is "a confusion of explanation with exculpation". Responsibility doesn't require behavior to be uncaused, as long as behaviour responds to praise and blame. Moreover, it is not certain that environmental determination is any less threatening to free will than genetic determination. 20 Neuroscience • It has become possible to study the living brain, and researchers can now watch the brain's decision-making "machinery" at work. A seminal experiment in this field was conducted by Benjamin Libet in the 1980s, in which he asked each subject to choose a random moment to flick her wrist while he measured the associated activity in her brain (in particular, the build-up of electrical signal called the readiness potential). Although it was well known that the readiness potential preceded the physical action, Libet asked whether the readiness potential corresponded to the felt intention to move. To determine when the subject felt the intention to move, he asked her to watch the second hand of a clock and report its position when she felt that she had the conscious will to move. 21 Experimental psychology Experimental psychology’s contributions to the free will debate have come primarily through social psychologist Daniel Wegner's work on conscious will. In his book, The Illusion of Conscious Will Wegner summarizes empirical evidence supporting the view that human perception of conscious control is an illusion. Wegner observes that one event is inferred to have caused a second event when two requirements are met: 1.The first event immediately precedes the second event, and 2.The first event is consistent with having caused the second event. For example, if a person hears an explosion and sees a tree fall down that person is likely to infer that the explosion caused the tree to fall over. However, if the explosion occurs after the tree falls down (i.e., the first requirement is not met), or rather than an explosion, the person hears the ring of a telephone (i.e., the second requirement is not met), then that person is not likely to infer that either noise caused the tree to fall down. 22 23 In Eastern philosophy In Hindu philosophy • The six orthodox (astika) schools of thought in Hindu philosophy do not agree with each other entirely on the question of free will. For the Samkhya, for instance, matter is without any freedom, and soul lacks any ability to control the unfolding of matter. The only real freedom (kaivalya) consists in realizing the ultimate separateness of matter and self. For the Yoga school, only Ishvara is truly free, and its freedom is also distinct from all feelings, thoughts, actions, or wills, and is thus not at all a freedom of will. The metaphysics of the Nyaya and Vaisheshika schools strongly suggest a belief in determinism, but do not seem to make explicit claims about determinism or free will. • A quotation from Swami Vivekananda, a Vedantist, offers a good example of the worry about free will in the Hindu tradition. “Therefore we see at once that there cannot be any such thing as free-will; the very words are a contradiction, because will is what we know, and everything that we know is within our universe, and everything within our universe is moulded by conditions of time, space and causality. ... To acquire freedom we have to get beyond the limitations of this universe; it cannot be found here.” 24 In Eastern philosophy In Buddhist philosophy Buddhism accepts both freedom and determinism (or something similar to it), but rejects the idea of an agent, and thus the idea that freedom is a free will belonging to an agent. According to The Buddha, "There is free action, there is retribution, but I see no agent that passes out from one set of momentary elements into another one, except the [connection] of those elements." Buddhists believe in neither absolute free will, nor determinism. It preaches a middle doctrine, named pratitya-samutpada in Sanskrit, which is often translated as "inter-dependent arising". It is part of the theory of karma in Buddhism. The concept of karma in Buddhism is different from the notion of karma in Hinduism. In Buddhism, the idea of karma is much less deterministic. The Buddhist notion of karma is primarily focused on the cause and effect of moral actions in this life, while in Hinduism the concept of karma is more often connected with determining one's destiny in future lives. 25 In Jewish Philosophy • Jewish philosophy stresses that free will is a product of the intrinsic human soul, using the word neshama (from the Hebrew root n.sh.m. or . מ.ש.נmeaning "breath"), but the ability to make a free choice is through Yechida (from Hebrew word "yachid", ,יחידsingular), the part of the soul which is united with God, the only being that is not hindered by or dependent on cause and effect (thus, freedom of will does not belong to the realm of the physical reality, and inability of natural philosophy to account for it is expected). 26 In Islamic Philosophy • In Islam the theological issue is not usually how to reconcile free will with God's foreknowledge, but with God's jabr, or divine commanding power. al-Ash'ari developed an "acquisition" or "dual-agency" form of compatibilism, in which human free will and divine jabr were both asserted, and which became a cornerstone of the dominant Ash'ari position. In Shia Islam, Ash'aris understanding of a higher balance toward predestination is challenged by most theologists. Free will, according to Shia Islamic doctrine is the main factor for man's accountability in his/her actions throughout life. All actions taken by man's free will are said to be counted on the Day of Judgement because they are his/her own and not God's. 27 In Christian Philosophy • • The theological doctrine of divine foreknowledge is often alleged to be in conflict with free will, particularly in Reformed circles. For if God knows exactly what will happen, right down to every choice one makes, the status of choices as free is called into question. If God had timelessly true knowledge about one's choices, this would seem to constrain one's freedom. This problem is related to the Aristotelian problem of the sea battle: tomorrow there will or will not be a sea battle. If there will be one, then it seems that it was true yesterday that there would be one. Then it would be necessary that the sea battle will occur. If there won't be one, then by similar reasoning, it is necessary that it won't occur. This means that the future, whatever it is, is completely fixed by past truths—true propositions about the future. However, some philosophers follow William of Ockham in holding that necessity and possibility are defined with respect to a given point in time and a given matrix of empirical circumstances, and so something that is merely possible from the perspective of one observer may be necessary from the perspective of an omniscient. Some philosophers follow Philo of Alexandria in holding that free will is a feature of a human's soul, and thus that non-human animals lack free will. 28 In Christian Philosophy • The philosopher Søren Kierkegaard claimed that divine omnipotence cannot be separated from divine goodness. As a truly omnipotent and good being, God could create beings with true freedom over God. Furthermore, God would voluntarily do so because "the greatest good ... which can be done for a being, greater than anything else that one can do for it, is to be truly free." Alvin Plantinga's "free will defense" is a contemporary expansion of this theme, adding how God, free will, and evil are consistent. 29 Is there any freedom for an actor on a stage in time and space? Does existence as physical entities in time and space allow any genuine choices? 30 A community of Inquiry on Free Will vs Determinism • CLICK ON THIS LINK FOR THE STIMULUS FOR A DISCUSSION ON THE PROBLEM OF FREE WILL (You might like to print this material out and distribute it to the class.) 31 Bibliography • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Bischof, Michael H. (2004). Kann ein Konzept der Willensfreiheit auf das Prinzip der alternativen Möglichkeiten verzichten? Harry G. Frankfurts Kritik am Prinzip der alternativen Möglichkeiten (PAP). In: Zeitschrift für philosophische Forschung (ZphF), Heft 4. Dennett, Daniel . (2003). Freedom Evolves New York: Viking Press ISBN 0-670-03186-0 Epstein J.M. (1999). Agent Based Models and Generative Social Science. Complexity, IV (5). Gazzaniga, M. & Steven, M.S. (2004) Free Will in the 21st Century: A Discussion of Neuroscience and Law, in Garland, B. (ed.) Neuroscience and the Law: Brain, Mind and the Scales of Justice, New York: Dana Press, ISBN 1932594043, pp51–70. Goodenough, O.R. (2004) Responsibility and punishment, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society: Biological Sciences (Special Issue: Law and the Brain), 359, 1805–1809. Hofstadter, Douglas. (2007) I Am A Strange Loop. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0465030781 Kane, Robert (1998). The Significance of Free Will. New York: Oxford University Press ISBN 0-19-512656-4 Lawhead, William F. (2005). The Philosophical Journey: An Interactive Approach. McGraw-Hill Humanities/Social Sciences/Languages ISBN 0-07-296355-7. Libet, Benjamin; Anthony Freeman; and Keith Sutherland, eds. (1999). The Volitional Brain: Towards a Neuroscience of Free Will. Exeter, UK: Imprint Academic. Collected essays by scientists and philosophers. Morris, Tom Philosophy for Dummies. IDG Books ISBN 0-7645-5153-1. Muhm, Myriam (2004). Abolito il libero arbitrio - Colloquio con Wolf Singer. L'Espresso 19.08.2004 http://www.larchivio.org/xoom/myriam-singer.htm Nowak A., Vallacher R.R., Tesser A., Borkowski W. (2000). Society of Self: The emergence of collective properties in self-structure. Psychological Review. 107 Schopenhauer Arthur (1839). On the Freedom of the Will., Oxford: Basil Blackwell ISBN 0-631-14552-4. Van Inwagen, Peter (1986). An Essay on Free Will. New York: Oxford University Press ISBN 0-19-824924-1. Velmans, Max (2003) How Could Conscious Experiences Affect Brains? Exeter: Imprint Academic ISBN 0907845-39-8. Wegner, D. (2002). The Illusion of Conscious Will. Cambridge: Bradford Books Williams, Clifford (1980). Free Will and Determinism: A Dialogue. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Co. Wikipedia- Free Will- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Free_will 32