Understanding - National Union of Teachers

advertisement

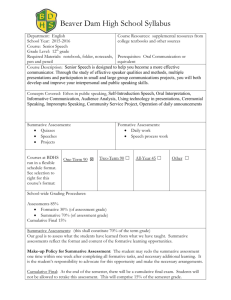

Section 2 The nature of the assessment task There are three key questions: • What are we doing when we assess? • How can we be sure that we are accurate in our assessments? • What different approaches are there? © Curriculum Foundation 1 In Unit 5 of the first programme, we looked at what it is that we are actually trying to do when we assess. In essence we are trying to find out what someone has learned, either as we go along (formative) or at the end (summative). And the bit of learning that we are interested in is usually to do with the aims we set in our lesson, unit or whole curriculum. Or we might be checking before we start to see whether they have already learned what we are about to teach them (initial assessment). The learning concerned is actually contained inside someone’s head. © Curriculum Foundation 2 Yes, it’s a picture of the neural networks of Any idea what this is? the brain. What about this next picture? © Curriculum Foundation 3 These are the synapses – where nerve cells interconnect. When we learn something, a new connection is made and the pathway becomes more complex. © Curriculum Foundation 4 So, if learning is about making new connections in the brain, then assessment is about finding out what new connections have been made. Perhaps the process should look like this. (That’s a brain they’re all looking at, by the way. This is a GCSE exam of the future.) © Curriculum Foundation 5 As we cannot actually get inside our pupils’ brains, we just have to do the best we can. Assessment is not an exact science. In order to find out what is going on inside someone’s brain, we have to observe their behaviour in certain controlled situations. At the simplest, we ask them some questions and see what they say. If they say “Paris” when we ask them what is the capital of France, we conclude that they know what the capital of France is. So the big issue for assessment is how valid are the conclusions we can draw from our observations. Simple pieces of knowledge are easy enough, but it starts getting more complex when we get into deeper understanding. Can we really conclude that someone understands something complex from the basis of their answers to some questions? And would everyone respond similarly to the same questions, even if they had equal understanding? © Curriculum Foundation 6 Do you remember ‘reliability’ and ‘validity’ from Unit 5 of the first Programme? Reliability in assessment means that whoever carries it out would come to the same conclusion. Validity means that we are actually assessing the thing we want to assess. Unfortunately, the two are often at the opposite ends of a line of tension. The more reliable an assessment is, the less valid it seems to be. And vice versa. We gave IQ tests as an example. They are high in reliability, but we are not sure if they are measuring intelligence or the ability to answer IQ test questions – so low in validity. Assessments made by teachers in the course if their work are often the most valid, but there is always a question of subjectivity and whether all teachers would come to the same conclusion. So they are low on reliability. Validity Reliability © Curriculum Foundation 7 We mention “know” and “understand” here – and these are some of the ‘building blocks’ of the curriculum that we looked at in Unit 1. Do you remember what they were? They are important to letting us look into the brain, and to deal with the issues of validity and reliability. © Curriculum Foundation Unit 1 looked at these ‘building blocks’ of the curriculum: Knowledge Possession of information Skills Ability to perform mental or physical operation Understanding Development of a concept: putting knowledge in a framework of meaning If you recall, each of these levels of expectation had some related verbs that made them explicit. These help us unlock what is in the brain. Knowledge State, name, label, draw, identify, describe Skills Carry out, perform, find, investigate, explore Understanding Explain, justify, analyse, give reasons for These are the verbs that also help us make the assessments. Knowledge Skills Understanding But what implications do these three forms of learning have for assessment? This is what we shall be looking at across this programme of Units. But here is a short outline to go on with. © Curriculum Foundation 11 Knowledge is on the whole the easy bit to assess because usually a simple question will be sufficient. We can be both valid and reliable in our assessment of knowledge. Not only that, we can assess whole classes at a time because we can do it through written papers. This is probably why we are so keen on doing it. Understanding is much harder to assess because this is where we really need to get inside the brain. Because we cannot actually do so, we need to look for ‘proxy measures’ such as the ability to explain or give reasons. These will give us some idea about the extent of understanding. This is best done through oral questioning of individual students in a series of different situations over time. Much more expensive – and much less popular. It also runs into issues of reliability. © Curriculum Foundation 12 So, that’s all very technical – but this Unit is supposed to be about making use of assessment! This is where we come back to those pairs of assessment words: Formative summative Diagnostic evaluative Initial - ipsitive Did you notice some definitions appearing in earlier slides? Did you spot them? In fact, these six terms are all different uses of assessment. © Curriculum Foundation 13 Here are some short definitions: • Initial is to establish a baseline or starting point • Formative is to check how learning is progressing to make adjustments to the course or to teaching as you go along • Summative is to get a final picture of learning – often for reporting or accountability reasons or to award a qualification • Diagnostic is to find out why someone is not learning as well as they should • Evaluative is to find out how well a programme or institution is doing (rather like the SATs) • Ipsative is finding out how well someone in doing in relation to their previous performance. © Curriculum Foundation 14 Of course, all of these are uses that we will wish to make of assessment at some point in a year: establishing a baseline or starting point, getting a final picture of learning, finding out why someone is not learning as well as they should, finding out how well someone in doing in relation to their previous performance. You might also want to find out how well a lesson or unit of work went or, if you are a school leader, how well a class or the whole school is doing. But most importantly as teachers, we want to check how well learning is progressing so that we can make adjustments to our teaching as we go along. This is the formative use, and there is much more to follow about this in this unit. © Curriculum Foundation 15 In Unit 1, we referred to the Note for inspectors: use of assessment information during inspections in 2014/15 This states that inspectors will: • spend more time looking at the range of pupils’ work to consider what progress they are making in different areas of the curriculum • talk to leaders about schools’ use of formative and summative assessment and how this improves teaching and raises achievement • evaluate how well pupils are doing against relevant age-related expectations as set out by the school and the national curriculum (where this applies) © Curriculum Foundation 16 So Ofsted see both formative and summative as important. But to make any use at all of assessment, we have to be clear about what sort of learning we are assessing: knowledge, understanding or skills. They each have their different methods. As we have seen, knowledge is the most straightforward. Understanding is fairly straightforward if it can be done orally – the issue is one of time. But skills, especially mental skills, are difficult. We shall look at these separately in the next section. © Curriculum Foundation 17