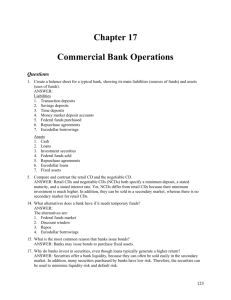

Managing the Investment Portfolio

advertisement