The Nature and Quality of Attachment

advertisement

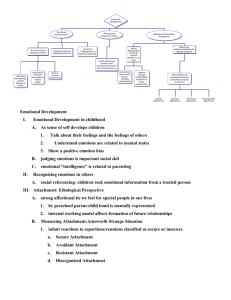

Chapter Six Emotional Development and Attachment Explanations of emotional development: Geneticmaturational, cognitive, and learning. Genetic-maturational, cognitive, and learning may each may be important for different aspects of emotional development. Explanations of emotional development: Geneticmaturational, cognitive, and learning. Genetic-Maturational explanations: 1.) Twin studies: MZ twins are more similar than DZ twins in when they begin to smile and how often they smile (sociability); same for fear of strangers and general fearfulness (behavioral inhibition) 2.) Smiling occurs at 46 weeks conceptual age, regardless of when baby is born. I.e., premies smile 6 weeks after they should have been born. Explanations of emotional development: Geneticmaturational, cognitive, and learning. Genetic-Maturational explanations: 3.) Stranger distress occurs at same age in all cultures regardless of childrearing practices. Separation Protest (infant's distress at being separated from mother, from ~6 mos. to 39 mos.) also occurs in all cultures at about the same time. 4.) Performance anxiety occurs around 18-24 mos. Concerned about being evaluated. (Shame, embarrassment would be typical emotions.) Explanations of emotional development: Geneticmaturational, cognitive, and learning. Cognitive perspective: 1.) Infants acquire mental representations (= schemata) and become better able to assimilate new events to schemata they already have. (This is a Piagetian meaning of assimilation.) 'Confronting a novel event causes buildup of tension; the infant responds with cognitive effort to master the meaning of the event; when the infant is successful, tension is released and he smiles.' (p. 216) = Smile of assimilation; reflects intrinsic motivation as central to cognitive development. Explanations of emotional development: Geneticmaturational, cognitive, and learning. Cognitive perspective: 2.) Context effects in fear of stranger (see above) can be explained by increasing cognitive sophistication. E.g., how close the mother is, whether the stranger is smiling or sober. Explanations of emotional development: Geneticmaturational, cognitive, and learning. Functionalist perspective: 1.) Combines aspects of the cognitive and learning explanations into a unified theory. 2.) Emotions are linked to goals. For example, how would emotions like hope, joy, frustration, anger, and fear be linked to goals? Some goals are innate: Baby wanting to be near mother; love, sex, rock n’ roll Some goals are learned: Wanting a new car 3.) Emotions are also linked to establishing and maintaining social relationships. (Be able to give some examples where we use emotional information in social relationships.) Perspectives on emotional development Learning perspective: 1.) Some parents may reinforce smiling more than others and some may be more effective in getting their children to control their emotions. (This competes with the genetic explanation for individual differences in fearfulness.) 2.) Some fears can be learned by classical conditioning, operant conditioning, or social referencing (social learning) (e.g., seeing that mom is afraid of a bee). Early Emotional Development: Carroll Izard Timetable of emotional facial expressions: Birth: Startle, disgust, distress, 'rudimentary smile' -i.e., reflexive smile, not responsive to external events. 4-6 weeks: True smile in response to social situations. 2-1/2-3 mos.: anger, interest, surprise, sadness 7 mos.: fear 6-8 mos.: shyness 12-36 mos.: pride, guilt, embarrassment, contempt, etc.-the 'social emotions.' These require greater cognitive sophistication and a sense of self. Early Emotional Development: Alan Sroufe 1.) Dates emergence of emotions later than Izard because he is unwilling to consider baby as having real emotions until baby is capable of cognitive appraisals How does anger differ from distress? Early Emotional Development: Alan Sroufe 2.) Differentiation (later emotions evolve out of earlier emotions; emotions become more differentiated; babies start out with distress—a global negative emotion; this differentiates into other negative emotions like anger, defiance, and rage. Wariness at 4–5 mos. differentiates into: stranger distress (9–11 mos), anxiety and fear (12–17 mos), shame (18–35 mos) guilt (36–54 mos) (Some say guilt develops later). Early emotional Development: Alan Sroufe 3.) Emotions become more psychologically (cognitively) based with age. E.g., distress versus anger: Distress has no cognitive component; newborns are distressed if they feel pain, but they don't direct anger at a specific person inflicting the pain until later in the first year. Fear does not develop until 7 months of age; requires cognitive ability to differentiate between familiar versus unfamiliar people. 4.) Emotions are more contextually sensitive with age. With age, infants respond emotionally to the meaning of the situation; e.g., laughter in response to tickling versus laughter when mom makes a funny face. Early Emotional Development Two types of emotions: Primary emotions (i.e., startle, distress, happiness, fear, ) Secondary emotions (i.e., shame, pride, guilt) require more cognitive sophistication. There are gender differences in emotional expressiveness: Girls > Boys The Beginnings of Specific Emotions Smiling and Laughter Smiling and laughter are the first expressions of pleasure Smiling: Reflex smiling: Birth to 3-4 weeks. Spontaneous, not in response to any stimulus. Weeks 3-8: Smile in response to external elicitors-bouncing, faces, especially faces. (Could it be an evolved bias?) Special smile toward mother at 10 mos., the Duchenne Smile; face 'lights up with pleasure, including wrinkles around the eyes. The Beginnings of Specific Emotions: Smiling and Laughter Girls smile more than boys' could be evolved bias to greater social interest; this results in more social interaction for girls. Smiling is central to infant social interaction, playing, pleasurable socializing Figure 6.2: laughter in infancy is increasingly caused by social (making faces) and visual stimuli (jack-in-the-box); less by tactile (e.g., tickling); 3-5-year-olds: 'acting silly' Laughter at stimuli (percent) What Makes Children Laugh? 35 Social 30 Visual 25 20 Tactile 15 10 Auditory 5 0 4-6 7-9 Age (in months) Fig. 6-2 10-12 The Beginnings of Specific Emotions: Fear Wariness (3 mos.): distress in response to events they can't assimilate; strangers are objects of interest and wariness, but not immediate negative reaction. Fear (9 mos.): negative reaction to event with specific meaning, such as a stranger; implies greater cognitive sophistication than with wariness. what to express under what circumstances. The Beginnings of Specific Emotions: Fear Individual differences in fearfulness: Kagan: behaviorally inhibited children are shy, introverted; respond with fear and increased heart rates to mildly stressful situations. 'Fearful Temperament' Contextual Features: Less fear at home or in mother's lap than in lab or away from mom. Less fear if mom is not afraid and reacts positively. This is social referencing: getting emotional cues from others. If mom is happy, baby sees this expression and is less afraid. Stranger characteristics: Strange child less fearsome than adults or a midget; probably child-like facial features are the cue; also if stranger is smiley and positive, baby is less afraid. The Onset of Stranger Distress Number of Children 14 Compares faces 12 10 Shows distress Looks sober 8 6 4 2 0 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Age (in months) Fig. 6-3 10 11 12 The Beginnings of Specific Emotions: Fear Separation protest – a fear that is universal and peaks in Western infants at about 15 months Separation anxiety sometimes reappears in other forms at later ages: e.g., day care, baby sitters, Separation Protest Percentage of Children who cried when mother left 100 African Bushman 80 60 40 Antiguan (Guatemala) 20 0 Guatemalan Indian 5 10 15 Israeli (kibbutzim) 20 25 Age (in months) Fig. 6-5 30 35 The Beginnings of Specific Emotions: Fear Infants use social referencing to know how to act in uncertain situations: Visual Cliff Study: Babies attend to mothers’ emotional expressions to get information on what to do. An expression of fear means “Stop.” The Beginnings of Specific Emotions: Pride, Guilt, Jealousy, and Shame Pride, Guilt, Jealousy, and Shame: The Self-Conscious Emotions Emerge toward middle of second year (~18 mos.) Require a sense of self; Rouge test: Before this age, children show no embarrassment when seeing themselves in a mirror with rouge on their face What’s That On My Nose? 80 70 60 Lewis & BrooksGunn’s study 50 40 Amsterdam’s study 30 20 10 0 9-12 15-18 Age (in months) Fig. 6-10 21-24 The Beginnings of Specific Emotions: Pride, Guilt, Jealousy, and Shame True guilt emerges only in middle childhood, around age 9 when children have a clear sense of personal responsibility: 'I felt guilty because I didn't turn in my homework out of laziness.' Younger children will say they are guilty but seem not to understand that their own responsibility is critical: “I felt guilty when my brother and I had boxing gloves on and I hit him too hard. . . . sometimes I don’t know by own strength.” Younger children may say they feel guilty even if they had no control over what happened. The Beginnings of Specific Emotions: Pride, Guilt, Jealousy, and Shame Differentiating between pride and shame is linked to task performance and responses from others 3-year olds: “easy” and “difficult”: More pride if task is difficult; more shame if task is easy. Differentiating “joy” vs. pride; “sadness vs. shame”; solving a not particularly difficult problem resulted in joy; solving a difficult problem produced pride. failing a difficult task resulted in sadness; failing an easy task resulted in shame. 2.5 Pride (=orange), Shame (=green), and Task Difficulty 2 1.5 1 0.5 0 Easy Difficult Task difficulty Fig. 6-7 Regulating Emotions Starts with sucking thumb (pre-natally), then more active methods like turning away, selfdistraction by 18 mos. Emotions more controlled and modulated as children move from infancy to toddlers This involves greater inhibitory control = effortful control with development of prefrontal cortex; textbook emphasizes learning, but much of this is maturational. Regulating Emotions As children get older: Less frequent emotions, less intense, more conventionalized. Children learn emotional display rules (what to express under what circumstances) beginning at age 2 when they exaggerate or minimize emotion in response to others; 9-10 years old, children can smile when unhappy. The Development of Attachment Attachment is closely related to emotional development Forms in second half of first year Evidenced by separation protests Enhances parents’ effectiveness in later socialization of their children Evolves over first 2 years of life The Development of Attachment Theories of attachment Psychoanalytic theory: attachment is linked to gratification of innate drives—basically the same as learning theory Learning theory: Traditionally, primary drive of hunger is reduced by primary reinforcer (food) and secondary reinforcer is one who feeds The Development of Attachment Harlow’s experiment Harlow: monkeys are comforted by soft “contact comfort”, not feeding Harlow and Zimmerman's (1959) experiment on monkeys: Cloth surrogate preferred over wire-mesh surrogate; this implies that babies innately like the contact comfort provided by the soft terrycloth surrogate. Babies also form attachments to fathers even though the fathers don't feed them. Therefore, babies don't learn to like contact by being fed. It's there to start with. This destroyed both the psychoanalytic and learning views. The Development of Attachment Theories of attachment Cognitive developmental theory: Attachment depends on infants differentiating between mom and others and understanding that people continue to exist even when baby can't see them Piaget called this object permanence. These are cognitive achievements. Objection: But can this account for the intense emotional reaction of separated infants? Increasing cognitive sophistication means physical proximity to attachment figures lessens in importance as children grow Increasing cognitive sophistication means that psychological contact maintained through words, smiles, and looks The Development of Attachment Theories of attachment Bowlby’s ethological theory: Infant attachment has roots in instinctual infant responses important for survival and protection: Crying, sucking, clinging. Attachment is an adaptation designed to protect the baby by keeping it close to mom. Adaptation = a mechanism designed by natural selection to perform a particular function. The Development of Attachment Theories of attachment Bowlby’s ethological theory: Based partly on animal’s imprinting process: A sensitive period for attaching to mom. Infants have innate ability to engage in social signaling (i.e., smiling and crying) These abilities play active role in formation of attachment. Parents also have innate abilities to respond to their baby’s eliciting behaviors. Attachment is a quality of a relationship, not a trait of the baby. Babies may have different attachments with different people (e.g., mom vs. dad). The Development of Attachment Attachment Evolves in stages or steps Develops for those regularly interacted with such as fathers, siblings, and peers Father-child interaction affected by culture and type of society one lives in Mothers and fathers differences in play modes or styles continue as children grow The Development of Attachment Phases in Development of Attachment 1.) Preattachment (0-2 mos.): Indiscriminate social responsiveness 2.) Attachment in the making (2-7 mos.): Recognition of familiar people 3.) Clear-cut attachment (7-24 mos.): Separation protest; wariness of strangers, intentional communication 4.) Goal-corrected partnership (24 mos. on): Relationships more two-sided: Children understand parent's intentions, plans, goals, and needs. Fathers and Attachment 1. Fathers can become attached to babies and engage in many of the same behaviors with babies. 2. Fathers also care for child at higher levels than in the old days, but they are less involved than mothers in routine care. Fathers and Attachment 3. Mother predominance in childcare is generally true, but there are examples of cultures where fathers play a larger role in care: the Aka in Africa; but this is not generally true of hunter-gatherer societies. 4. Father tend to play more physically with children: rough and tumble play, etc. But it is not universal; children like it more than relatively sedentary play with mothers--more arousing. Assessing Attachment: Ainsworth’s Strange Situation Test: Table 6.4 1. Mother, baby, and observer 2. Mother and baby 3. Stranger, mother and baby 4. Stranger and baby 5. Mother and baby 6. Baby alone 7. Stranger and baby 8. Mother and baby Episodes #5 and #8 are Reunion Episodes The Nature and Quality of Attachment Early attachment formation is not uniform Many seem to form highly secure attachments Assessment is based on the Strange Situation and Ainsworth’s classifications Styles of caregiving are linked to attachment; sensitive care linked to secure attachments, and unavailable or rejecting linked to insecurity Deficient forms of parenting often result in approach/avoidance behavior in children The Nature and Quality of Attachment Tested at ~1 year of age (6 mos. to 2 yrs.), at a time when child uses mother as a SECURE BASE: Secure Base: the attachment object is seen by the child as a base from which to explore new things and a haven in times of distress. Four Classifications: A, B, C, and D The Nature and Quality of Attachment 1.) Secure (B Babies) (60% OF U.S. SAMPLE): ACTIVELY SEEK PROXIMITY AND CONTACT AT REUNION; EXPLORE WHILE MOM IS AROUND, SEE HER AS A SECURE BASE; OFTEN DISTRESSED DURING SEPARATION, BUT CALM DOWN QUICKLY AT REUNION 2.) Insecure-avoidant (A Babies); 20% : OFTEN DO NOT CRY MUCH AT SEPARATION; DO NOT SEEK PROXIMITY AND ACTIVELY AVOID THE MOTHER AT REUNION; DO NOT RESIST CONTACT IF MOTHER INITIATES IT; DO NOT CRY MUCH AT REUNION The Nature and Quality of Attachment 3.) Insecure-resistant (C Babies); 10-15%: VERY UPSET AND DISTRESSED DURING SEPARATION; ACTIVELY SEEK PROXIMITY AND CONTACT AT REUNION RESIST CONTACT AT REUNION, OFTEN SHOWING ANGER; CONTINUE CRYING AT REUNION; THEY DO NOT CALM DOWN EASILY AT REUNION 4.) Insecure-disorganized (D Babies): DISORIENTED, DAZED, REPETITIVE BEHAVIORS; Extreme Approach/Avoidance Caregiving and attachment status 1.) Secure attachment (B babies): associated with SENSITIVE CARE: Responsive and consistently available when baby is in genuine need. Mothers continually adjust behavior to infant so that there is INTERACTIVE SYNCHRONY, A SMOOTH-FLOWING DANCE; Mothers use exaggerated speech and facial expressions. Baby gets excited and averts gaze; mother doesn't intrude. Like a sine wave. Dyadic Interaction during motherinfant playful interaction Dyadic Interaction is like a sine wave: Baby becomes excited when looking at mom but turns away when too aroused. Caregiving and attachment status 2.) Insecure Avoidant attachment (A babies): UNAVAILABLE, REJECTING, UNRESPONSIVE TO BABY'S SIGNALS; mothers are intrusive rather than sensitive in dyadic interaction. 3.) Insecure Resistant (C babies): INCONSISTENTLY AVAILABLE; mothers unresponsive or uninvolved in dyadic interaction Caregiving and attachment status 4.) Insecure Disorganized (D babies) associated with neglect or abuse. Approach/avoidant behavior is common; 82% of abused infants had disorganized attachment vs. 19% of non-abused infants. Mothers often depressed; little mutual eye contact and mutual responsiveness; lots of gaze aversion. The Internal Working Model Internal Working Model: A person's mental representation of himself as a child, his parents, and the nature of the interactions with the parents as he reconstructs and interprets their interaction. Hypothesis: The IWM tends to result in people recreating their relationships with their own children. Recollections of relationship with parents tends to predict attachment with children. One study found this effect when based on recollections of women before their babies were born, This controls for the possibility that current relationship with the child would color perceptions of relationship with parents. Temperament and attachment classification Temperament: Some studies find association between difficult temperament and insecure attachment. Text suggests that if there is an effect it is the result of interactions with the context: Babies with difficult temperament whose mothers are isolated or have no social support are more likely to have insecure attachment; but temperament by itself is a poor predictor of insecurity of attachment. Moral: Good mothering beats difficult temperament. Stability of Attachment Classification Stability: Attachment is highly stable; One study: 100% of children secure at 12 mos. were secure at 6 yrs; 66% for disorganized; but there are notable exceptions. Lowered stress (e.g., less marital tension) leads to increase in attachment security, More negative life events (job loss, divorce, illness, abuse) leads to decrease in attachment security. The Nature and Quality of Attachment: Cross-cultural variation Attachment studies show interesting comparisons between cultures: Box 6.3: Israeli and Japanese babies more likely to be Resistant (C) babies Israeli cared for by metapelet rather than parent; may not be so sensitive Japanese mothers are very close to baby, share bed, etc. German babies more likely be Avoidant (A) babies Consequences of Attachment Quality: Cognitive Development Cognitive Development: Age 2: Secure babies more enthusiastic, persistent, curious, exploratory; higher level symbolic play with mother Age 7: In task where mother encouraged them to read, securely attached children less distractible, paid more attention to mother, required less discipline. This is a Vygotsky-type study: Cognitive development occurs in a social context with adults. Consequences of Attachment Quality: Social Development Social Development: Age 1-3½: More positive emotions, more empathy, less aggressive, socially skilled, more friends. Follow-up at Age 11: children securely attached as babies were more confident, more socially competent, higher selfesteem; Consequences of Attachment Quality: Social Development Peer relations: Securely attached children spent more time with peers. Form friends with other secure children. Consequences of Attachment Quality: Social Development Peer relations: Securely attached children spent more time with peers. Form friends with other secure children. IWM is proposed as mechanism: 5-yearold Children who are insecurely attached are more likely to interpret an ambiguous event (bumping into another child) as done with hostile intent Consequences of Attachment Quality: Social Development Peer relations: Securely attached children spent more time with peers. Form friends with other secure children. IWM is proposed as mechanism: 5-year-old Children who are insecurely attached are more likely to interpret an ambiguous event (bumping into another child) as done with hostile intent Securely attached children also better at understanding emotions and regulating their emotions. They recall more positive emotional experiences, while insecurely attached children recall more negative experiences. Consequences of Attachment Quality: Social Development Children may have different attachment categories with different parents; Having a secure relationship with both parents shows the strongest relationships with positive outcomes. Day Care and Attachment 1999 census: 10 million children under the age of six spend substantial time being cared for by non-parents. 50% of children under 5 spend many hours a week in some form of day care i.e., daycare provided by non-family member either in the child’s home or a day care facility. Who Is Caring For Our Preschoolers? 5.1% 24% Parents 15.4% Other relatives Other Child care centers Family-child care homes In-home care 25% 29.6% 0.9% Fig. 6-11 Day Care and Attachment 1.) Children in daycare still are attached to their parents. 2.) Amount of time in daycare affects nature of parent-child relationship negative correlation between time in day care and sensitivity of mother at 3, 6, and 15 mos. Children found to be somewhat less affectionate toward mothers. 3.) Children who begin day care before age 1 more likely to be insecurely attached. High Quality Day Care may Compensate for Negative Effects on Attachment High quality daycare can compensate: Better outcomes if there is a secure attachment with daycare provider. Daycare quality affected by: 1.) staff turnover: High turnover is a risk factor. 2.) teacher training: Better trained teachers more likely to have secure attachment with children. High Quality Day Care may Compensate for Negative Effects on Attachment Poor quality daycare associated with aggression and delinquency. High quality daycare associated with higher language and cognitive skills. Effects of quality of daycare may be found in kindergarten: Poor quality daycare associated with more destructiveness and less consideration of others. The Nature and Quality of Attachment Quality of child care appears linked to social class of families using the services Low-income Affluent Are Child Care and Enrichment Programs Only for the Affluent? Percent of 3- to 5-year-olds enrolled in preschool 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 Families Fig. 6-12 Percent of schools offering extendedday and enrichment programs (b) (a) 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 Neighborhoods ETHOLOGICAL THEORY OF ATTACHMENT: JOHN BOWLBY A HYBRID THEORY: (1) BIOLOGICAL SYSTEMS (2) LEARNING (3) COGNITIVE SCHEMES Ethological Theory of Attachment: Biological Systems 1.) ATTACHMENT AS AN ADAPTATION ADAPTATION = A BEHAVIOR OR MORPHOLOGICAL FEATURE DESIGNED BY NATURAL SELECTION IN ORDER TO PERFORM A PARTICULAR FUNCTION FUNCTION OF ATTACHMENT IS TO PROVIDE PROTECTION FOR HELPLESS INFANTS. ATTACHMENT IS AN ADAPTATION DESIGNED BY NATURAL SELECTION TO KEEP THE BABY CLOSE TO THE MOTHER AS A SOURCE OF PROTECTION; IT IS A PROXIMITY MAINTAINING SYSTEM Ethological Theory of Attachment: Biological Systems 2.) ETHOLOGICAL IDEA OF 'NATURAL CLUE' = AN INNATE CONNECTION BETWEEN A STIMULUS AND AN AFFECTIVE (EVALUATIVE) RESPONSE STIMULUS AFFECTIVE, EVALUATIVE RESPONSE S R+ (CONTACT COMFORT, AFFECTIONATE TOUCHING, MUTUAL GAZING AND SMILING) SWEET TASTES S R -(MOTHER ABSENT; STRANGER PRESENT; BITTER TASTES) Ethological Theory of Attachment: Biological Systems Natural Clues: THE CONNECTION BETWEEN THE STIMULUS AND THE AFFECTIVE RESPONSE IS INNATE, UNLEARNED; Bottom line: BABIES COME INTO THE WORLD WITH LIKES AND DISLIKES Ethological Theory of Attachment: Biological Systems 3.) MOTHER AND BABY ARE BIOLOGICALLY PROGRAMMED FOR SOCIAL INTERACTION a.) BABIES' BEHAVIORS FOR MAINTAINING CONTACT: CRYING, LOCOMOTION, "MOLDING TO MOTHER'S BODY"; b.) FOR FACILITATING INTERACTION: APPEARANCE OF BABY, SMILING, VOCALIZING, MAKING EYE CONTACT SOCIAL INTERACTION IS INNATELY PLEASURABLE FOR MOTHER AND BABY (INVOLVES NATURAL CLUES) Ethological Theory of Attachment: Cognition and Learning 1.) MOTHER AS SECURE BASE FOR EXPLORATION: THE SET POINT: Changes with Development and with the Situation B M MOTHER WITHIN SET POINT: BABY EXPLORES M B MOTHER EXCEEDS SET POINT: ATTACHMENT BEHAVIORS TRIGGERED, EXPLORATION CEASES Ethological Theory of Attachment: Cognition and Learning DISCRETE SYSTEMS IDEA: ATTACHMENT SYSTEM INTERACTS WITH THE EXPLORATION SYSTEM, THE PLAY SYSTEM, AND OTHER SYSTEMS. IF SAFE, THEN PLAY, EXPLORE IF STRANGER IS PRESENT, THEN STOP PLAY, LOOK FOR MOTHER IF HUNGRY, STOP PLAY AND EXPLORATION, SEEK FOOD DISCRETE SYSTEMS IDEA: Evolutionary Psychology Ethological Theory of Attachment: Cognition and Learning 2.) INTERNAL WORKING MODEL (IWM) OF MOTHER = A MODEL (SCHEMA) OF WHAT MOTHER IS LIKE a.) BUILT UP FROM EXPERIENCE (LEARNING) b.) EMPHASIS ON SENSITIVITY AND RESPONSIVITY c.) RESULTS IN A MODEL OF FUTURE RELATIONSHIPS; RESISTANT TO CHANGE Ethological Theory of Attachment: Cognition and Learning IWM FOR A (AVOIDANT) CHILD: PEOPLE ARE NOT AVAILABLE WHEN I NEED HELP IWM FOR B (SECURE) CHILD: PEOPLE WILL BE SENSITIVE AND RESPONSIVE WHEN I NEED HELP IWM FOR C (AMBIVALENT, RESISTANT) CHILD: PEOPLE ARE UNRELIABLE WHEN I NEED HELP; SOMETIMES THEY ARE RESPONSIVE, SOMETIMES NOT. The End