Rutgers School of Law-Newark 2014 David Cohn Appellate

Rutgers School of Law-Newark

2014 David Cohn Appellate Advocacy Competition

Instructions and Problem

1

Dear Competitors,

Thank you for participating in this year’s David Cohn Appellate Advocacy Competition at Rutgers

University School of Law – Newark. We hope you find the competition to be a challenging and enjoyable learning experience during your law school career.

Below are detailed instructions regarding the competition rules, the appellate brief, and oral argument rounds. The background, lower court opinions, U.S. Supreme Court’s writ of certiorari, and appendices are also included. We recommend verifying that you have all necessary sections before proceeding. If you still have questions after reviewing the instructions below, contact David Sisk at davesisk@gmail.com.

Although the problem is designed to be challenging, as you develop familiarity with the case law and facts, your tasks should become easier. We look forward to your participation and wish you the best of luck!

Sincerely,

David Sisk &

Christopher Mitchell

Rutgers Moot Court Board Co-Chairs

Rutgers School of Law – Newark

2

Part I: INTRODUCTION

You are responsible for reading and understanding all rules and instructions in this packet.

This packet contains instructions and rules for the competition as well as the competition problem.

Competitors should assume they are counsel on certiorari appeal from a ruling of the Court of

Appeals for a mock federal district.

Competitors may refer to any real statute and to any real case that has not been enacted or decided before the problem release date.

The competition is primarily designed to be an academic exercise that will help you develop your appellate advocacy skills.

Statements made by the authors of the fact pattern and court opinions do not necessarily reflect their real-life views regarding legal issues or any other subject.

Part II: REGISTRATION

REGISTRATION FOR ACADEMIC CREDIT WITH RUTGERS SCHOOL OF LAW

Competitors wishing to receive one (1) soft academic credit can add the competition with Dean

Garbaccio.

Competitors currently registered for Moot Court Board credit may not register for competition credit as well.

REGISTRATION WITH THE RUTGERS MOOT COURT BOARD

All competitors must register with the Rutgers Moot Court Board using the registration form in this packet.

The registration form must be submitted to the Moot Court Board office (Room 391) by

Thursday, February 20, 2014 at 8:00 PM. o Failure to submit the form to the Moot Court Board office by the deadline may result in disqualification from the competition. o If you need to submit the form as an e-mail attachment, you must obtain permission from a Moot Court Board Co-Chair, i.e., David Sisk or Christopher Mitchell.

COMPETITION IDENTIFICATION NUMBER

• The registration form contains a line for a unique Competitor ID Number.

• The number is chosen by the competitor and must contain exactly nine (9) digits.

• Briefs are scored anonymously using this number. Do not share this number with anyone and do not choose a number that can be easily deduced by another competitor or a Moot Court Board member.

PART III: COMPETITION BRIEF

GENERAL REQUIREMENTS

During the first stage of the competition, all competitors must submit a written brief.

The brief’s general format must follow the United States Supreme Court rules for how to brief a case before that court unless noted otherwise. Any disparities between this format and other formats competitors may be aware of (e.g., Legal Research and Writing I & II) should be resolved in favor of following the U.S. Supreme Court formatting.

Competitor names should not appear anywhere on the brief.

O Include only the nine-digit Competitor ID Number in the upper right hand corner on every page of every brief submitted.

3

O A breach of anonymity may result in disqualification from the competition.

PAGE MINIMUMS/LIMITS

Competitors using the brief to satisfy the writing requirement

O Competitors wishing to use the brief to satisfy the law school’s writing requirement should indicate this on the registration form.

O Briefs must be a minimum of twenty-five (25) full pages to satisfy the writing requirement.

O Eight (8) copies should be submitted to the Moot Court Board.

Competitors not using the brief for the writing requirement

O Briefs must be a minimum of eighteen (18) pages.

O Seven (7) copies of the brief should be submitted to the Moot Court Board.

All participants must reach the end of the last page of the brief to satisfy the minimum requirements.

O E.g., a brief reaching the first line of page 18 does not count as a full eighteenth page and may result in disqualification from the competition for failing to satisfy the minimum page requirement.

IMPORTANT: BRIEF ORGANIZATION FOR CALCULATING MINIMUM PAGE REQUIREMENTS

In calculating which sections count towards reaching the minimum page requirements, the following rubric should be used:

O The pages contained in the following sections must be numbered in Roman Numerals and do NOT count towards the required minimum page requirement:

Caption Page

Questions Presented

Table of Contents

Table of Authorities

O Should competitors choose to include any of the following sections in the brief, these sections should be numbered with Arabic Numerals and DO satisfy the required page minimum:

Opinion(s) Below

The Opinion Below section, if included, can be satisfied with a full citation to the lower court opinion(s). E.g., “the opinion(s) below are located at Smith v. . . .”

Standard of Review

Statement of the Case

Summary of the Argument

Argument

Conclusion

CITATIONS, FONT, & MARGIN FORMATTING

All citations should conform to the most recent edition of A Uniform System of Citations (the

“Bluebook”).

O Any other citation format or a lack of proper citations will result in a point deduction.

4

Briefs should be written in 12 point Century font and double-spaced. o Any other font, size, or spacing will result in a point deduction.

Brief margins should be 1” around the entirety of the document (left, right, top, and bottom margins). o Any other margin spacing will result in a point deduction.

Citations to the Record (e.g., the factual background) may be made to the specific page of the problem packet. Participants need not cite to the line of the specific page of the Record.

GRADING CRITERIA

• Briefs will be evaluated and graded anonymously by the Moot Court Board using the following criteria: writing style, strength and logical development of arguments, thoroughness and accuracy, and adherence to the rules stated in this packet.

PROCEDURAL HISTORY

• Competitors should omit the “Procedural History” and “Statement of Jurisdiction” sections normally included in appellate and U.S. Supreme Court briefs.

CHOOSING A SIDE

• Competitors may write on behalf of either the Petitioner or Respondent in the brief. Note: competitors will argue for both sides in the oral argument rounds as described below.

NUMBER OF COPIES REQUIRED

Participants using the competition to satisfy the writing requirement must submit eight (8) copies of the brief to the Moot Court Board office.

All other competitors must submit seven (7) copies.

RECOMMENDATIONS AND SOURCE RULES

• Statutes and cases cited throughout the lower court opinions should not be construed as representing the entire body of law on either issue.

Some cases may be controlling on a given issue and some may not be.

• In researching the problem, competitors are not limited to the sources cited in the lower court opinions alone. Competitors are strongly encouraged to consult both primary materials (case law, statutes, regulations, etc.) and secondary legal research materials (newspapers, magazines, law journals, etc.).

• If competitors cite any resources other than reported case law, statutes, law journals, or anything else not easily located, one copy of such material(s) must be submitted with the brief.

ETHICAL REQUIREMENTS FOR BRIEFS

• The brief must be the exclusive work of the competitor.

No other person may review or edit the brief.

Competitors may not exchange briefs with any other participant or discuss brief content.

Other ethical requirements for the competition are stated below.

BRIEF SUBMISSION DEADLINE

Physical briefs are due by Thursday, February 27, 2014 at 8:00 PM in the Moot Court Board office, Room 391. o Briefs will not be accepted after this time. No exceptions will be made.

5

o Electronic submissions will not be accepted.

• Do not forget to include the Competitor ID Number. Failure to include all necessary information may result in tardy submission, which will bar the registrant from competing and obtaining academic credit.

PART IV: ORAL ARGUMENT

GENERAL MATTERS

Competitors are not limited to arguments raised in their briefs when preparing for oral argument.

O Competitors are encouraged to analyze their opponent’s oral arguments when preparing to argue for the opposing side.

Each competitor will argue for twenty (20) minutes. A five (5) minute rebuttal is available for the

Appellant.

Competitors may rely on any statutes and case law published prior to the release of the problem.

O Opinions published after the problem release date may not be raised in the competitor’s brief or oral argument.

ORAL ARGUMENT ROUNDS

The competition is comprised of three rounds of oral argument:

O Preliminary Round (consisting of two oral arguments per competitor)

O Semi-Final Round (four competitors selected)

O Final Round

PRELIMINARY ROUND

The Preliminary Round requires each competitor to argue twice (one argument on behalf of the

Petitioner and one on behalf of the Respondent).

O Sides for the first oral argument will be assigned randomly. The sides will be announced once the preliminary round oral argument schedule is released.

Oral arguments will take place on the evenings of: o Monday, March 3, 2014 through Thursday, March 6, 2014; and o Monday, March 10, 2014 through Thursday, March 13, 2014.

Every competitor will argue once during the week of March 3, 2014 (Week 1 Argument), and once during the week of March 10, 2014 (Week 2 Argument).

Arguments will be scheduled to start at 6:00 PM and 7:00 PM.

DETERMINING THE SEMI-FINALISTS

The composite score by which the four semi-finalists will be calculated is as follows: o Appellate Brief Score: 40% o Oral Argument Score (Week 1 Argument): 30% o Oral Argument Score (Week 2 Argument): 30%

The competitors with the four highest composite scores will advance to the Semi-Final Round, which will take place Monday, March 24 at 6:00 PM and 7:00 PM.

SEMI-FINAL ROUND

6

The first place competitor will argue against the fourth place competitor.

The second place competitor will argue against the third place competitor.

The competitor in each pairing with the higher preliminary round composite score will choose to argue on behalf of the Petitioner or Respondent.

The composite score by which the two finalists will be calculated is as follows: o Appellate Brief Score: 40% o Semi-Final Oral Argument Score: 60%

The two competitors who receive the higher composite scores within their respective Semi-Final

Rounds will advance to the Final Round.

The competitor with the highest composite Semi-Final Round score will choose to argue on behalf of the Petitioner or Respondent during the Final Round.

FINAL ROUND AND AWARDS BANQUET

The Final Round argument will take place Thursday, April 3, 2014 in the Baker Trial Courtroom

(Room 125).

The composite score by which the winner will be calculated is as follows: o Appellate Brief Score: 40% o Final Round Oral Argument Score: 60%

The competitor receiving the higher composite score within the final round will be the winner.

Immediately following the Final Round argument, the Moot Court Board will announce three awards at a banquet held in the Berson Board Room. o In addition to announcing and awarding the winner and runner-up of the Final Round argument, the Board will announce the winner of the Best Brief Award. o Scholarship awards will be given at the awards banquet and the winners will be named

Schildkraut Scholars for the upcoming year. o The Best Brief Award will be given to the individual submitting the highest scoring brief, regardless of oral argument score.

REGIONAL COMPETITION TEAM

Both Final Round competitors and the author of the highest scoring brief will represent the school in the Regional Competition in the Fall, 2014 semester.

Participation in this competition reflects your acknowledgement and agreement that, should you advance to the finals or submit the highest scoring brief, it is your responsibility to represent Rutgers in the Regional Competition during the Fall, 2014 semester and to satisfy all requirements related to it. o These requirements include, but are not limited to, participating in oral argument practice rounds with the team and the academic advisor and following all procedures set by the host of the Regional Competition.

In the event that the author of the highest scoring brief advances to the Final Round argument, the third member of the Regional Competition team will be the semi-finalist who received the highest Semi-Final Round score without advancing to the Final Round. o All requirements stated in the previous paragraphs shall apply to that competitor.

PART V: ETHICAL REQUIREMENTS

MOOT COURT BOARD RULES

7

o Competitors may not discuss the problem, issues, brief, or the substance of the oral argument with other competitors, law students, faculty members or attorneys, except for questions asked:

1) at practice arguments organized and supervised by the Moot Court Board Co-

Chairs; or

2) directly to the Board’s Co-Chairs. o Even superficial conversations related to the competition constitute grounds for dismissal and revocation of academic credit. o Competitors are prohibited from consulting with WestLaw or LexisNexis representatives for substantive research assistance. o Competitors may practice their oral arguments with non-law school students and other people not associated with the practice of law, e.g., non-lawyer family members.

Practicing arguments with members of the legal community is prohibited even if the individual is not a law school student, faculty, or staff member.

THE LAW SCHOOL HONOR CODE

Participants who violate these rules may also be subjected to disciplinary action under the Rutgers Law School Honor Code.

The Honor Code and the Rutgers University Disciplinary Hearing Code and Procedures

(see the Student Handbook) apply to participation in this competition, and to the use of all reference and other materials.

COMPLAINTS OF CHEATING/WRONGDOING, DECISIONS, AND APPEALS

• The Moot Court Board is an autonomous organization that reserves the right to decide disputes arising from any competition it sponsors.

• Allegations of cheating or wrongdoing brought to the Moot Court Board must be verbally raised during the night of the competition to the bailiff and followed by a written complaint to the Co-Chairs within 24 hours of the incident.

• Allegations will be considered and decided by the Moot Court Board Co-Chairs. Appeals may be made within 24 hours of written notification of the Board’s decision.

• The Board Co-Chairs and Academic Adviser will hear all appeals.

• All decisions are final and binding upon the competition and its contestants.

PART VI: QUESTIONS

• All questions regarding the competition must be submitted in writing to David Sisk at davesisk@gmail.com or in the Moot Court Board office co-chair mailbox.

PART VII: MCB SPONSORED PRACTICE SESSION

The Moot Court Board Co-Chairs reserve the right to hold a practice oral argument session for competitors.

The practice session is held at the discretion of the Co-Chairs and does not form part of the yearly David Cohn Appellate Advocacy Competition.

The Co-Chairs will contact competitors regarding the date and time of the practice session to be held, if applicable.

Practice sessions are to include one or both Co-Chairs and an individual competitor.

O The Moot Court Board prohibits mooting of arguments between competitors.

8

O Competitors may moot their arguments individually and receive feedback from the

Co-Chairs during this session only.

O Co-Chair feedback may be general in scope and may purposely exclude critiques of certain aspects of the competitor’s argument.

9

2014 DAVID COHN APPELLATE ADVOCACY COMPETITION

REGISTRATION FORM

** SUBMIT TO THE MOOT COURT BOARD OFFICE (ROOM 391) BY

THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 20, 2014 at 8:00 PM. **

Name: ________________________________________

Competitor ID Number (chosen by competitor): __________________________

This is the number that must appear on each page of your brief. Briefs will be graded anonymously and you will be identified by this number.

E-Mail Address: _________________________________

Phone Number: _________________________________

Preliminary Round Scheduling Conflicts (in order of importance):

1. _________________________________________

2. _________________________________________

3. _________________________________________

4. _________________________________________

5. _________________________________________

The Moot Court Board will try to accommodate requests, but cannot guarantee all requests will be honored. It is the responsibility of the competitor to be available on nights their arguments are scheduled. Absences from classes that are a result of competing will not be excused. The Semi-Final

Round and Final Round dates cannot be changed. Only list conflicts for the Preliminary Round.

Graduation Writing Requirement (please select one):

[ ] Yes, I intend to use the competition brief to satisfy the school’s writing requirement.

[ ] No, I do not intend to use the competition brief to satisfy the school’s writing requirement.

If you have taken Appellate Advocacy, please circle your instructor to avoid potential conflicts of

interest: Evenchick Mandel Orloff Russell

Note: the submission of this form to the Moot Court Board does not constitute registration for academic credit. If you are seeking academic credit, you must register with Dean Garbaccio.

**FAILURE TO RETURN THIS FORM BY THE DEADLINE WILL RESULT IN DISQUALIFICATION**

10

Strickland v. Kraftwerk, Inc.

11

FACTUAL BACKGROUND

KRAFTWERK INC., FOUNDERS

1.

Jacob Kraft was born on an Ohio Amish farm in 1949. He was the first of seven children. His mother was a member of a moderately conservative Amish sect called the New Order Amish.

His father was originally a Catholic from Warren, Ohio who concealed his non-Amish origin.

2.

The Amish settlement where Jacob was raised stressed non-assimilation with the dominant culture, conformity in dress and appearance, marriage to others within the group, nonparticipation in military service, and a disciplined lifestyle with an emphasis on simple living.

The community remained separate from the United States government in a variety of ways.

Geographically they lived close together in Amish settlements, relying on horse and buggy for transportation. Use of certain modern technologies was permitted but only if they did not threaten the community of believers. Electricity was restricted in homes and use of telephones was limited to shanties separate from the home’s main structure.

Rural life, manual labor and humility were prominent values Jacob learned at a young age.

Pennsylvania Dutch, a variation of the German language, was also the predominant language

Jacob spoke as a child.

3.

When Jacob was five years old his parents were excommunicated and shunned by the Amish community for holding Bible studies in their home and for associating with non-Amish (“English”)

Christians. The Kraft family relocated to Middlefield, Ohio and joined an Amish-Mennonite church where many other excommunicated Amish were members. Jacob was baptized at this church.

4.

Jacob and his eleven siblings were enrolled in public schools. Following high school, Jacob abandoned rural life for the urban manufacturing steel-town of Youngstown, Ohio. He attended

Youngstown State University where he graduated with a bachelor’s degree in Philosophy. He later received his MBA from Cleveland State University where he also became a Cleveland

Browns football fan. However, Jacob eventually returned to rural life in Middlefield to work for his father’s farming business.

5.

Jacob met his wife, Ruth, in 1971 on a business trip to Newstate where he was ordering farming equipment. Ruth’s father owned and operated a successful farming equipment manufacturing company. He and his family were members of a conservative Methodist church.

6.

Ruth and her father were intrigued by Jacob because of his Amish roots and religious values. A year-long courtship began during which time Ruth began adopting elements of the Amish lifestyle. She relocated to Ohio where she and Jacob were married in 1972. Ruth planned to be a

12

stay-at-home mother. She began producing handmade Amish arts and crafts together with several Amish friends. Ruth sold these items at local fairs and suburban shops where she found a niche market for Amish related products.

7.

Ruth’s father died in 1974 and left much of his savings to her. This money was used to expand

Ruth’s arts and crafts business, which was officially founded as Kraftwerk Inc. (“Kraftwerk”) in

1974. The company began as a way for Jacob and Ruth to maintain a connection with the Amish community and to capitalize on a growing demand for handmade arts and crafts. They expressly established Kraftwerk to conform to their personal religious standards.

KRAFTWERK INC.

8.

Kraftwerk was founded and is officially headquartered in Newstate City, Newstate as a for-profit, closely held S-Corporation. The business is owned and operated by most of the Kraft family. The managing operators include Jacob and Ruth, their son John and their daughter Rebecca Kunce.

9.

The Krafts own 100% of Kraftwerk’s voting shares, each board member is a Kraft, and the family guides management decisions. Kraftwerk only acts at the direction of the Krafts.

10.

Kraftwerk produces and supplies a variety of Amish and Mennonite related goods and services.

The products and services include handmade Amish arts and crafts, Amish schnitz pie, organically raised meat and produce, religious books and certain manual labor construction services. Kraftwerk also owns and operates a popular Amish themed restaurant in Columbiana,

Ohio called “Das Dutch Haus” that will soon expand to include a 51-room colonial boutique Inn.

Rebecca manages the restaurant and hotel division. Das Dutch Haus does most of its business during summer church retreats.

11.

Many Kraftwerk products are sold and distributed at local auctions, markets and towns surrounding Amish communities but the company also has contracts with several national forprofit chains. These chains include Michaels, Hobby Lobby, Jo-Ann Stores, Trader Joe’s, Whole

Foods, and even Wal-Mart in a limited number of regional locations around the country.

12.

Most of the company’s 2,000 employees are not Amish but about 500 are. Most of the Amish employees are craft workers but a growing number are farmers and construction workers who are overseen by Jacob’s farming division. Most of the Amish employees live and work in the counties surrounding Trumbull, Holmes and Mahoning in Ohio but at least 100 can also be found in New Wilmington, Pennsylvania. Most full-time employees are paid up to 80% above minimum wage.

13.

As the trend for organic products grows, Kraftwerk has expanded its organic foods division and additional offices are being opened around the Midwest. Jacob’s organic foods division will soon be the majority of the company’s annual gross income, which is expected to continue growing.

13

Fewer Amish farmers are expected to be employed as a higher efficiency of output becomes important. The Krafts remain adamant that Amish themed marketing and values will continue.

14.

Although they no longer adhere to a purely Amish way of life, the Kraft family remains deeply religious and traditional in their views and lifestyle. They attribute Kraftwerk’s success to their religious principles and to their faith in God.

15.

Kraftwerk continues to be operated with religious principles in mind. The Certificate of

Incorporation cites a commitment to “honoring the Lord in all we do by operating the company in a manner consistent with Biblical principles, family, community and humility.” The Kraftwerk website also describes the company as “a faith-based company dedicated to applying religious principles to everyday life.”

16.

Kraftwerk does not conduct business on Sundays, which costs the company millions in annual sales. The company also refuses to engage in business activities that facilitate or promote activities such as consumption of alcohol, drugs or tobacco. Kraftwerk gives to a variety of nonprofit organizations that emphasize these values.

17.

The Certificate of Incorporation further states: “In order to effectively serve our owners, employees, and customers, the Board of Directors is committed to serving families and communities by establishing a work environment that builds character, strengthens individuals, and nurtures communities by sharing the Lord’s blessings. We believe that it is by God’s grace that Kraftwerk has endured. He has been faithful in the past and we trust Him for our future.”

EMPLOYEE HEALTH COVERAGE

18.

Most Kraftwerk Amish employees do not buy commercial insurance or participate in Social

Security. Instead, most choose to participate in “Church Aid,” which is an informal self-insurance plan for helping Amish church members with catastrophic medical expenses, including several genetic disorders that are common throughout Amish settlements.

19.

Healthcare practices are varied amongst the Amish settlements where Kraftwerk employees reside. The practices include folk, herbal, homeopathic, and western biomedicine. Use of the western biomedical healthcare system is mostly crisis oriented. Because Kraftwerk employs individuals from numerous Amish settlements and sects, no uniform or cooperative system exists amongst the employees.

20.

The Krafts believe it is part of their religious duty to provide generous health benefits to both their Amish and non-Amish employees. The Krafts include certain types of preventive care coverage in their employee health plan beyond what is required by law. However, the Krafts and most of their Amish employees do not practice any form of birth control. They are against abortion and find artificial insemination, eugenics and stem cell research to be inconsistent with

14

their values. They believe human life begins when the sperm fertilizes an egg and that it is immoral to facilitate any act that causes the death of a human embryo.

21.

The Kraftwerk Board of Directors adopted “The Kraft Family Statement on the Sanctity of

Human Life,” which states the family’s belief that human life begins at conception and that the family is against being involved in termination of human life through abortion or any other acts that involve taking human life.

FEDERAL HEALTHCARE MANDATE

22.

In 2010 Congress passed the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (the “ACA”). The ACA requires employers with fifty or more employees to provide a minimum level of health insurance to employees. The ACA requires non-exempt group plans to provide coverage without cost-sharing for preventive care and screening for women in accordance with guidelines created by the Health Resources and Services Administration (the “HRSA”), a sub-agency of the Health and Human Services (the “HHS”). The HRSA adopted guidelines requiring non-exempt group plans to cover all Food and Drug Administration (“FDA”) approved contraceptive methods.

23.

The ACA requires employers with employment-based group health plans covered by the

Employee Retirement Income Security Act to provide certain types of preventative health services. These include twenty FDA-approved contraceptive methods, ranging from oral contraceptives to surgical sterilization. Four of the twenty approved methods can function by preventing the implantation of the fertilized egg. The remaining methods function by preventing fertilization.

24.

ACA exemption is an extension of the Social Security exemption. A number of entities are partially or fully exempted from the contraceptive-coverage requirement, such as those with group health plans established or maintained by religious employers. A “religious employer” is defined as an organization that: 1) has the inculcation of religious values as its purpose; 2) primarily employs persons who share its religious tenets; 3) primarily serves persons who share its religious tenets; and 4) is a non-profit organization described in a provision of the IRC that refers to churches and to the exclusive religious activities of any religious order.

25.

Certain other non-profit organizations are given accommodations, including religious institutions of higher education, which are subject to a temporary safe harbor provision that exempts them from covering contraceptive services. If a business does not make significant changes to its health plans after the ACA’s effective date, those plans are considered

“grandfathered” and are also exempt from the contraceptive-coverage requirement.

26.

Members of a “recognized religious sect or division,” as specified in Section 1402 of the Internal

Revenue Code, are exempt from ACA mandates. The exemption includes most Amish sects that have been in existence prior to December 31, 1950. A self-sustaining and self-insuring

15

community must show a history of self-sustenance in order to be exempt. The Social Security

Administration must recognize a particular religious sect as being “conscientiously opposed to accepting any insurance benefits.”

27.

Kraftwerk and the Krafts do not qualify for full or partial exemption from the ACA.

LEGAL CLAIM

28.

The Krafts object to being forced to provide, through their corporation, health insurance that would cover the four contraceptive procedures that would prevent implantation of an embryo.

The Krafts believe that providing this coverage would violate their personal religious beliefs and their corporation’s express values. They do not object to the sixteen other methods they would be required to cover.

29.

The Krafts assert that if they refuse to provide such contraceptive-methods, they will be exposed to substantial tax penalties in an amount that will put an undue financial burden on their business. The Krafts sought temporary injunctive relief from the federal mandate imposed by the ACA.

30.

The plaintiffs’ suit challenges the ACA’s contraceptive-coverage requirement under the Religious

Freedoms Restoration Act (the “RFRA”) and the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment.

The plaintiffs simultaneously moved for a preliminary injunction on the basis of their RFRA and

Free Exercise claims. The District Court denied the motion and the Twelfth Circuit Court of

Appeals reversed.

16

United States District Court for the Western District of Newstate

Docket No. 10-061987

Kraftwerk, Inc., Petitioner v.

Kathleen Strickland, Secretary of Health and Human Services, Respondent

MEMORANDUM AND ORDER

Judge: Victoria Orneta, United States District Judge

Opinion by: Victoria Orneta

Opinion

Plaintiffs, Jacob Kraft, Ruth Kraft, John Kraft and Rebecca Kunce sued Kathleen Strickland,

Secretary of the United States Department of Health and Human Services (“HHS”), and other government officials and agencies challenging regulations issued under the Patient Protection and

Affordable Care Act (the PPACA or the “ACA”). Specifically, plaintiffs object to the ACA’s requirement that employers with employment-based group health plans covered by ERISA provide certain types of preventative health services, including twenty FDA-approved contraceptive methods ranging from oral contraceptives to surgical sterilization – four of which prevent implantation of the fertilized egg.

Plaintiffs contend that providing this coverage would violate their personal religious beliefs and their corporation’s values. Moreover, plaintiffs argue from a legal standpoint that the ACA’s contraceptive-coverage requirement violates their rights under the Religious Freedoms Restoration Act

(“RFRA”) and the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment. Presently at issue is plaintiffs’ motion for a preliminary injunction in which they ask the court to prohibit defendants from enforcing the requirement against them, primarily on the basis of their RFRA and Free Exercise Claims.

17

Background

The ACA requires employers with employment-based group health plans covered by ERISA to provide certain type of preventative health services. These include twenty FDA-approved contraceptive methods, ranging from oral contraceptives to surgical sterilization. Four of the twenty approved methods can function by preventing the implantation of the fertilized egg. The remaining methods can function by preventing fertilization.

The Krafts are members of a family that own and operate Kraftwerk. Kraftwerk was founded and is officially headquartered in Newstate City, Newstate as a for-profit, closely held corporation organized as an S-Corporation. The business is owned and operated by the Kraft family. The managing operators include Jacob and Ruth Kraft (husband and wife), their son John and their daughter Rebecca Kunce.

The Kraft family remains deeply religious and traditional in their views and lifestyle. Kraftwerk is operated with express religious principles in mind. The statement of the incorporation cites a commitment to “honoring the Lord in all we do by operating the company in a manner consistent with

Biblical principles, family, community and humility.” The Kraftwerk website also describes the company as “a faith-based company dedicated to applying religious principles to everyday life.” Kraftwerk does not conduct business on Sundays and refuses to engage in business activities that facilitate or promote activities such as consumption of alcohol, drugs, or tobacco.

The Krafts and most of their Amish employees do not practice any form of birth control. They are against abortion and find artificial insemination, eugenics and stem cell research to be inconsistent with their values. The Krafts believe that human life begins when the sperm fertilizes an egg and that it is immoral to facilitate any act that causes the death of a human embryo.

Kraftwerk and the Krafts did not receive full or partial exemption from the ACA. The Krafts object to being forced to provide, through their corporation, health insurance that would cover the four contraceptive procedures that would prevent implantation of an embryo. The Krafts believe that providing this coverage would violate their personal religious beliefs and their corporation’s express values. The Krafts assert that if they refuse to provide such contraceptive-methods, they will be exposed to tax penalties in an amount that will put an undue financial burden on their business.

Plaintiffs seek a preliminary injunction to prevent defendants from enforcing the mandate against them, arguing that the mandate violates their statutory rights under the Religious Freedom

Restoration Act of 1993 and their right to free exercise of religion under the First Amendment.

Legal Standard

A preliminary injunction is a remedy that should “not be issued unless the movant’s right to relief is ‘clear and unequivocal.’” Kikumura v. Hurley, 242 F.3d 950, 955 (10th Cir. 2001). A movant must establish four factors to obtain a preliminary injunction:

1) That a movant will suffer irreparable injury unless the injunction issues; 2) that the threatened injury outweighs whatever damage the proposed injunction may cause the opposing

18

party; 3) that the injunction would not be adverse to the public interest; and 4) that there is a substantial likelihood of success on the merits. Id.

The plaintiffs have the burden of demonstrating that each factor weighs more heavily in their favor. Id. at 1188-89.

Past precedent has established that a more relaxed “probability of success” requirement may be applicable in certain instances where the moving party can assert that the three “harm” factors weigh in its favor. Id. at 1189. The movant “need only show questions going to the merits so serious, substantial, difficult and doubtful, as to make them a fair ground for litigation.” Id. This standard is not applicable where such injunction might change the status quo. Northern Natural Gas Co. v. L.D. Drilling, Inc., 697

F.3d 1259, 1266 (10th Cir. 2012). Defendants argue that plaintiffs are not seeking to maintain the status quo since the Krafts do not object to the sixteen other methods of contraception.

Precedent has also stated that the “liberal definition of the ‘probability of success’ requirement” does not apply “where a preliminary injunction seeks to stay governmental action taken in the public interest pursuant to a statutory or regulatory scheme.” Nova Health Systems v. Edmonson, 460 F.3d

1295, 1298 n.6 (10th Cir. 2006) (quoting Heideman, 348 F.3d at 1189). Here, plaintiffs are challenging a regulatory requirement that is mandated in the public interest; therefore, the liberal standard does not apply.

The District of Colorado reached a contrary conclusion to find that the liberal “likelihood of success” should be applied since the “government’s creation of numerous exceptions to the preventative care coverage mandate has undermined its alleged public interest.” Newland v. Sebelius,

881 F. Supp. 2d 1287 (D. Colo. 2012). Despite this finding, the court is obliged to observe that all government action (pursuant to a statutory scheme) is adopted in the interest of the public. Aid for

Women v. Foulston, 441 F.3d 1101, 115 n. 15 (10th Cir. 2006) (finding inappropriate the liberal standard to a regulation that required a minor to report voluntary sexual activity). Just as the court in Aid for

Women found the liberal standard inappropriate, this court presumes that the mandate here was taken in the public interest. Additionally, precedent in the Tenth Circuit has found that a challenge does not have to be an entire statutory scheme. Heideman, 348 F.3d at 1189. Therefore, even though the plaintiffs are only attacking a small part of the ACA’s regulation, such small part both 1) is an action taken in the public interest and 2) is one taken pursuant to the statute. Therefore, the liberal standard does not apply, and to obtain injunctive relief, the plaintiffs must show a substantial likelihood on the merits, in addition to the standard’s three other factors. We will evaluate the substantial likelihood on the merits by analyzing the two claims asserted by the plaintiffs.

Religious Freedom Restoration Act

RFRA applies standards that are more protective of religious exercise than the constitutional standards under the First Amendment. For one, the RFRA prohibits the federal government from substantially burdening a person’s exercise of religion, unless the government can prove that such

“burden” is the least restrictive means of furthering a legitimate and compelling government interest.

42 U.S.C. § 2000bb-1. The RFRA provides that:

19

(a)

(b)

In general Government shall not substantially burden a person’s exercise of religion even if the burden results from a rule of general acceptability, except as provided in subsection (b) of this section

Exception: government may substantially burden a person’s exercise of religion only if it demonstrates that application of the burden to the person – (1) is in furtherance of a compelling governmental interest; and (2) is the least restrictive means of furthering that compelling governmental interest. Id.

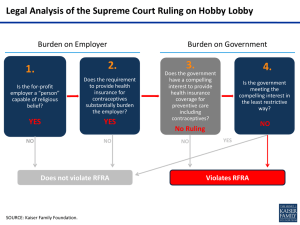

The threshold question here is whether all the plaintiffs are in a position to assert rights under the RFRA. This question depends on whether the corporate plaintiff qualifies as a “person” within the meaning of the statute. It is unquestionable to admit that the Krafts are entitled to assert its potential application to them. According to past case law, a “plaintiff establishes a prima facie claim under RFRA by proving the following three elements: (1) a substantial burden imposed by the federal government on a (2) sincere (3) exercise of religion.” Kikumura v. Hurley, 242 F.3d 950, 960 (10th Cir. 2001). If the plaintiff can establish such a claim, then the onus is on the government to prove that the regulation furthers a compelling governmental interest and is the least restrictive means of furthering that interest.

Id. at 961-62. Since this court does not question that the Krafts beliefs are sincerely held or that the mandate burdens the exercise of their religious beliefs, the critical question is therefore whether the mandate imposes a substantial burden on the Krafts for purposes of the RFRA. Plaintiffs make the argument that defendant’s requirements substantially burdens their religious exercise by forcing them to choose between following their convictions and paying a large amount of money in fines.

This court does not fail to express that the RFRA’s provisions do not just apply to any burden on religious exercise, but rather a substantial burden. Although no Twelfth Circuit precedent provides specific guidance, this court looks to the Seventh Circuit decision in Civil Liberties for Urban Believers v.

Chicago for observation on the meaning behind the word “substantial.” Civil Liberties for Urban

Believers v. Chicago, 342 F.3d 752 (7th Cir. 20013). Civil Liberties stresses the importance of the word

“substantial” and argues that the purpose of such word implementation serves to show that the RFRA did not intend to strike down all regulations that hindered ANY religious exercise; rather, it sought to preserve regulations that advanced a compelling governmental interest by the least restrictive means. Id. at 761. The Seventh Circuit court therefore concluded “a regulation that imposes a substantial burden on religious exercise is one that necessarily bears direct, primary and fundamental responsibility for rendering religious exercise…impracticable.” Id. This court has cited Civil Liberties with approval regarding what constitutes a “substantial burden,” emphasizing a sort of directness between the regulation and the individual’s right to religious exercise.

Other cases have shown that directness is more than just a mere roadblock in one’s religious exercise. See Kikumura, 242 F.3d at 955 (finding that a prisoner who was denied pastoral visits by a minister was a violation of the RFRA since it directly impeded on his ability to practice his religion);

Sherbert v. Verner, 374 U.S. 398, 404 (1963) (finding a directness between regulation and religious exercise where an individual was forced “to choose between following the precepts of her religion and forfeiting benefits, on the one hand, and abandoning one of the precepts of her religion in order to

20

accept work, on the other hand.”); Wisconsin v. Yoder, 406 U.S. 205, 218 (1972) (holding that compulsory attendance law required Amish plaintiffs “to elect between abandon[ing] belief[s] and be[ing] assimilated into society at large, or be[ing] forced to migrate to some other…region” as a substantial and direct burden). Moreover, the court in United States v. Lee found that “every person cannot be shielded from all the burdens incident to exercising every aspect of the right to practice religious beliefs.” United States v. Lee, 455 U.S. 252, 261 (1982).

Based upon these rules, the plaintiffs are unlikely to establish a “substantial burden” within the meaning of the RFRA. The mandate in question applies only to Kraftwerk, and not its officers or owners.

Further, the particular “burden of which plaintiffs complain is that funds, which plaintiffs will contribute to a group health plan, might, after a series of independent decisions by health care providers and patients covered by businesses’ plans, subsidize someone else’s participation in an activity that is condemned by plaintiff’s religion. O’Brien v. United States Dept. of Health and Human Svcs., 894 F. Supp.

2d 1149, 2012 WL 4481208, at *6 (E.D. Mis. 2012). It is also important to note that the Krafts no longer adhere to a purely Amish way of life. It can also be inferred, according to Lee, that once “followers of a particular sect enter into commercial activity as a matter of choice, the limits they accept on their own conduct…are not to be superimposed on the statutory schemes which are binding on others in that activity.” Lee, 455 U.S. at 261. In the case of the Krafts and Kraftwerk, a majority of the company’s 2,000 employees have different or no faith (while 500 of them, less than half, are Amish). Therefore, this mass number of employees might have different religious views and their possible rights relating to access to contraceptives are being affected on a constitutional dimension. And, in harping back to the mention of voluntary entrance into commercial activity, it is important to note that the Krafts are expanding into such an atmosphere by contracting with other for-profit secular chains; this also results in fewer Amish farmers expecting to be employed as a higher efficiency of output becomes important.

In summation, the Krafts, unlike those in the cases before us, have utterly failed to show that the burden on religious exercise is direct and personal.

First Amendment – Free Exercise of Religion

The First Amendment’s Free Exercise Clause states “Congress shall make no law respecting the establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” Plaintiffs contend that in order to exercise their religion, they must comply with their Amish values that prohibit them from providing coverage that allows for birth control, abortion, artificial insemination, eugenics and stem cell research.

The requirement under the ACA, they argue, violates their religious beliefs and substantially burdens their religious exercise. The purpose of the free exercise clause is “to secure religious liberty in the individual by prohibiting an invasions thereof by civil authority.” Sch. Dist. Of Abington Twp. v. Schempp,

374 U.S. 203, 223 (1963).

“While the First Amendment provides absolute protection to religious thoughts and beliefs, the free exercise clause does not prohibit Congress and local governments from validly regulating religious conduct.” Grace United Methodist Church v. City of Cheyenne, 451 F.3d 643, 649 (10th Cir. 2006). The free exercise clause does not serve to rule out a valid or neutral law of general applicability. See Lee, 455

21

U.S. at 263 n. 3. A law that is neutral need only be rationally related to a legitimate government interest.

Grace, 451 F.3d at 649. In the event that the law is not neutral and not generally applicable, the court should apply a strict scrutiny standard. Id. It is up to this court’s discretion to determine whether the plaintiffs are fighting a regulation that is non-neutral.

A law is neutral if its object is “something other than the infringement or restriction of religious practices” Id. The plaintiffs claim that the requirement is not neutral since it exempts some religious employers from compliance while compelling others (such as themselves) to provide coverage for contraceptive-methods they deem go against their religion. Plaintiffs ultimately believe that providing this coverage would violate their personal religious beliefs and the corporation’s express values.

Plaintiffs fail in asserting that such a law is non-neutral. Both parties concede that the requirement is secular in nature. There is no direct evidence that the exception is based on religious categorization. Id. at 652. Given the facts, it can be inferred that the religious employer exemption and the safe harbor provision in fact recognizes and protects the exercise of religion. The mere fact that such exceptions do not extend to the Krafts does not automatically mean that the regulation is non-neutral.

See O’Brien v. U.S. Dep’t of Health and Human Servs., 894 F. Supp. 2d 1149, ___ (E.D. Mo. 2012). This idea is enforced in Catholic Charities of the Diocese of Albany v. Serio: “To hold that any religious exemption that is not all-inclusive renders a statute non-neutral would be to discourage the enactment of any such exemptions – and thus to restrict, rather than promote, freedom of religion.” 859 N.E. 2d

459, 464 (N.Y. 2006). Plaintiffs therefore fail in asserting that such a law is non-neutral.

The plaintiffs must also prove, under their constitutional claim that “laws burdening religious practice must be of general applicability.” Church of the Lukumy Babalu Aye, Inc. v. Hialeah, 505 U.S.

520, 542 (1992). “The Free Exercise Clause protect[s] religious observers against unequal treatment, and inequality results when a legislature decides that the governmental interests it seeks to advance are worthy of being pursued only against conduct with a religious motivation.” Id. at 542-43. Plaintiffs fail to prove that the mandate is not generally applicable. The mandate applies to all individuals and corporations equally – any person who does not have a religious objection to contraceptive-methods must comply with the rules to the same extent as someone who has a religious objections. Therefore, the rules are generally applicable.

Given that this court finds the ACA requirement both neutral and generally applicable, the mandate is therefore subject to rational basis scrutiny under the First Amendment. The plaintiffs do not argue that there is no legitimate government interest for the mandate or that the regulations are not rationally related to protect that interest. Moreover, this court does not find that the mandate is unconstitutional. Applying the principles stated, the court concludes that plaintiffs have not established a likelihood of success as to their constitutional claims.

Conclusion

Plaintiffs have not shown a “clear and unequivocal” right to injunctive relief in light of the standards applicable to their request. Heideman, 348 F.3d at 1188. This court wholly understands that this advent of such regulations causes issues among many individuals and corporations. Nevertheless,

22

for the reasons previously stated, the court concludes that the plaintiffs have not made the necessary showing of a likelihood of success on the merits to warrant a preliminary injunction in the circumstances present.

For one, the plaintiffs have failed to demonstrate a probability of success on their Religious

Freedom Restoration Act claims. The plaintiffs have not established that compliance with the ACA requirements to provide coverage for contraceptive-methods would “substantially burden” their religious exercise. This failure asserts their shortcoming in establishing a prima facie burden under the

RFRA.

Second, the Krafts have not demonstrated a probability of success on their free exercise claims under the First Amendment. Although they have rights to challenge the regulation, they are unlikely to prevail because the required coverage for contraceptive-methods is both neutral and generally applicable.

Accordingly, the motion for preliminary injunction is DENIED.

IT IS SO ORDERED.

/s/ V. Orneta

Judge Victoria Orneta

United States District Judge,

United States District Court for the Western District of Newstate

23

United States Court of Appeals for the Twelfth Circuit (12th Cir.)

Docket No. 11-061987

Kraftwerk, Inc., Petitioner v.

Kathleen Strickland, Secretary of Health and Human Services, Respondent

Appeal from the United States District Court for the Western District of Newstate, (No. 10-061987)

Opinion of the Court filed by Chief Justice David B. JONES writing for a unanimous court.

INTRODUCTION

We decide today whether the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) and the Free Exercise

Clause cover the plaintiffs here: a corporation organized under the laws of Newstate, and the shareholders and owners of that corporation.

The corporation is a closely held family business whose owners abide by strong religious beliefs in operating their business and in their day to day lives. They contend that requirements of the Patient

Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 will force them to violate these strong religious beliefs.

Specifically, the plaintiffs contend that abiding by certain requirements that employers provide employees with coverage for contraceptive procedures will force them to either violate their belief that life begins at conception or face a tax penalty.

We hold that the corporation and its owners have standing to bring claims under the RFRA, and have established a likelihood of success on the merits of their claim. We remand the case to the district court for further proceedings on the three remaining preliminary injunction factors.

I.

Background

A.

Plaintiffs

The Krafts are the plaintiff founders, owners, and sole shareholders of Kraftwerk, the plaintiff corporation. The Krafts have strong religious beliefs which stem from their upbringing in religious communities.

24

Ruth Kraft began producing handmade Amish arts and crafts together with several Amish friends shortly after marrying Jacob Kraft in Ohio in 1972. Ruth sold these items at local fairs and suburban shops where she found a niche market for Amish related products.

When Ruth’s father died in 1974 and left much of his savings to Ruth, the money was used to expand Ruth’s crafts business, which was officially founded as Kraftwerk in 1974. Jacob and Ruth expressly established Kraftwerk to conform to their personal religious standards.

Plaintiff Kraftwerk is officially headquartered in Newstate City and is organized as a for-profit, closely-held corporation with S-Corporation status. The business is owned and operated by most of the

Kraft family including nine children. The managing operators include Jacob and Ruth, their son John and their daughter Rebecca Kunce.

Kraftwerk continues to be operated with express religious principles in mind. The statement of incorporation cites a commitment to “honoring the Lord in all we do by operating the company in a manner consistent with Biblical principles, family, community and humility.” The Kraftwerk website also describes the company as “a faith-based company dedicated to applying religious principles to everyday life.”

B.

Healthcare coverage

The Krafts and most of their Amish employees do not practice any form of birth control. They are against abortion and find artificial insemination, eugenics and stem cell research to be inconsistent with their values. The Krafts believe that human life begins when the sperm fertilizes an egg and that it is immoral to facilitate any act that causes the death of a human embryo.

C.

ACA

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (the PPACA or the “ACA”) requires employers with employment-based group health plans covered by ERISA to provide certain types of preventative health services. These include twenty FDA-approved contraceptive methods, ranging from oral contraceptives to surgical sterilization. Four of the twenty approved methods can function by preventing the implantation of the fertilized egg. The remaining methods function by preventing fertilization.

D.

Exemptions

Certain organizations are eligible for a partial or full exemption from the ACA’s contraceptivecoverage requirement. Specifically, entities with group health plans established or maintained by religious employers; certain non-profit organizations, including religious institutions of higher education, which are subject to a temporary safe harbor provision; and businesses which are “grandfathered” by not making significant changes to existing health plans after ACA’s effective date. A “religious employer” under the ACA is defined as an organization that: (1) has the inculcation of religious values as its purpose;

(2) primarily employs persons who share its religious tenets; (3) primarily serves persons who share its religious tenets; and (4) is a non-profit organization described in a provision of the IRC that refers to churches and to the exclusively religious activities of any religious order.

25

E.

Expected Effect of ACA

The Krafts maintain a health plan that provides insurance for Kraftwerk employees. Kraftwerk elected not to maintain the grandfathered status exemption.

The Krafts object to being forced to provide, through their corporation, health insurance that would cover the four contraceptive procedures that would prevent implantation of an embryo. The

Krafts believe that providing this coverage would violate their personal religious beliefs and their corporation’s express values. Specifically, because the four contraceptive methods to which the Krafts object prevent a fertilized egg (an embryo) from being implanted in the uterine wall, and because the

Krafts believe life begins at conception (fertilization), the Krafts object to being forced to provide this coverage. They do not object to the sixteen other methods they would be required to cover.

The Krafts assert that if they refuse to provide such contraceptive-methods, they will be exposed to tax penalties in an amount that will put an undue financial burden on their business.

The ACA indeed does impose certain penalties on non-exempt organizations for noncompliance with its requirements. If Kraftwerk does not follow the ACA’s requirements, the corporation will be subject to a penalty of $100 per employee per day until it complies. See 26 U.S.C. § 4980D(b)(1). With

2,000 employees, Kraftwerk estimates that it will be subject to a substantial financial penalty per year.

The Krafts sought temporary injunctive relief from the federal mandate imposed by the ACA.

The plaintiffs’ suit challenges the ACA’s contraceptive-coverage requirement under the Religious

Freedoms Restoration Act and the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment. The plaintiffs simultaneously moved for a preliminary injunction on the basis of their RFRA and Free Exercise claims.

The District Court denied the motion.

II.

RFRA

Plaintiff’s claims arise under the Religious Freedom Restoration Act. That Act states, in relevant part, that “[g]overnment shall not substantially burden a person’s exercise of religion . . . .” 42 U.S.C. §

2000bb-1(a). The RFRA goes on to outline an exception: “Government may substantially burden a person’s exercise of religion only if it demonstrates that application of the burden to the person (1) is in furtherance of a compelling governmental interest; and (2) is the least restrictive means of furthering that compelling governmental interest.” Id. § 2000bb-1(b). Thus, to establish a prima facie case under the RFRA, a plaintiff must show that the government substantially burdens a sincere religious exercise.

Kikamura v. Hurley, 242 F.3d 950, 960 (10th Cir. 2001). The government must then satisfy its burden by showing that the “compelling interest test is satisfied through application of the challenged law ‘to the person’—the particular claimant whose sincere exercise of religion is being substantially burdened.”

Gonzales v. O Centro Espirita Beneficente Uniao do Vegetal, 546 U.S. 418, 420 (2006) (quoting 42 U.S.C.

§ 2000bb-1(b)).

26

We must determine whether, under RFRA, Kraftwerk is “a person” exercising religion, whether

Kraftwerk’s religious exercise is substantially burdened by government action, and, if so, whether the government can demonstrate a narrowly tailored compelling government interest.

III.

Standing

A.

Introduction

We first address jurisdictional matters as to Kraftwerk and the Krafts. Specifically, we must determine whether Kraftwerk and the Krafts have Article III standing to pursue their claims in federal court, and whether the Krafts have satisfied prudential standing requirements in addition to those of

Article III.

B.

Kraftwerk

1.

RFRA

Because federal jurisdiction is limited by the Constitution to actions that qualify as “Cases” and

“Controversies,” a party that does not present a case or controversy within the meaning of Article III does not have standing to bring an action in federal court. To establish standing, a plaintiff must show an injury that is “concrete, particularized, and actual or imminent; fairly traceable to the challenged action; and redressable by a favorable ruling.” Monsanto Co. v. Geertson Seed Farms, 561 U.S. 139, —,

130 S. Ct. 2743, 2752 (2010) (citing Horne v. Flores, 557 U.S. 433, —, 129 S. Ct. 2579, 2591-92 (2009)).

Here, Kraftwerk faces an imminent injury, namely the loss of money if it does not comply with the ACA’s mandate by the effective date. This injury is traceable to the ACA’s contraceptive coverage requirement. Finally, Kraftwerk’s injury would be redressed if a court held the contraceptive coverage requirement was not enforceable as to them. We conclude, therefore, that Kraftwerk has standing under Article III.

C.

Krafts

1.

Article III Standing

The Krafts likewise must show that they, as individual plaintiffs, have standing to bring a federal action under Article III.

The Krafts allege they are injured because they must choose to violate their religious beliefs or subject their corporation to penalties for noncompliance with the ACA. It is clear that the Krafts’ injury is imminent; however, it must also be “concrete [and] particularized.” Monsanto, 130 S. Ct. at 2752.

The Krafts claim that any conduct that would aid others in using particular contraceptives would violate their sincerely held religious beliefs. Thus, their position as owners of Kraftwerk subjects them to two concrete and particularized injuries if they do not comply with the ACA: either violating the requirements of their religious beliefs, or risking financial failure of Kraftwerk.

27

The ACA causes this injury, and rendering it unenforceable as to the Krafts would redress it.

Thus, the Krafts have Article III standing to assert their RFRA claims.

2.

Prudential Standing

In addition to Article III’s standing requirements, there exist other restrictions on which class of persons may invoke the federal judicial power. Warth v. Seldin, 422 U.S. 490, 499 (1975). These so-called

“prudential standing requirements” must be met even if Article III’s standing requirements are satisfied,

id., and include the “shareholder standing rule,” which states that “conduct which harms a corporation confers standing on the corporation, not its shareholders.” Bixler v. Foster, 596 F.3d 751, 756 (10th Cir.

2010). Indeed, a shareholder of a corporation may not bring an action that belongs to the corporation or is “derivative” of the corporation’s injury. Id. at 758.

The ACA applies to Kraftwerk and the Krafts are the corporation’s sole shareholders. On its face, it appears as though the Krafts are bringing a derivative suit. However, because the Krafts’ alleged injury is direct and personal, the shareholder standing rule does not apply to them.

A corporation’s shareholders may suffer derivative financial harm while separately suffering a direct and personal injury. See Franchise Tax Brd. off Cal. v. Alcan Ltd., 493 U.S. 331, 336-37 (1990);

Grubbs v. Bailes, 445 F.3d 1275, 1277, 1280 (10th Cir. 2006). Although the Krafts may suffer financial harm through Kraftwerk for noncompliance with the ACA—harm which, on its own, is derivative and implicates the shareholder standing rule, e.g., Bixler, 596 F.3d at 758—their central alleged injury is that of the offense to their religious beliefs. Indeed, in order to comply with the ACA, they must affirmatively engage in conduct that violates their religion. This alleged injury is not purely financial; the Krafts have asserted rights independent of their shareholder status, and have satisfied prudential standing requirements.

IV.

Preliminary Injunction Standard

The district court denied Plaintiff’s motion for preliminary injunctive relief. Our standard of review for such a denial is abuse of discretion. Little v. Jones, 607 F.3d 1245, 1250 (10th Cir. 2010). To constitute an abuse of discretion, a district court must have denied a preliminary injunction based on an error of law. Westar Energy, Inc. v. Lake, 552 F.3d 1215, 1224 (10th Cir. 2009).

The party seeking a preliminary injunction must show: (1) a likelihood of success on the merits;

(2) a likely threat of irreparable harm to the movant; (3) the harm alleged by the movant outweighs any harm to the non-movant; and (4) a preliminary injunction is in the public interest. See, e.g., Winter v.

NRDC, 555 U.S. 7, 20 (2008).

The lower court ruled that Plaintiff is not protected by RFRA, and thus could not establish the first prong of the above preliminary injunction test, that Plaintiff would likely succeed on the merits of its action. For the reasons outlined below, we disagree.

28

V.

Merits

A.

Kraftwerk

The central issue in this appeal is Kraftwerk’s status as a for-profit corporation and whether this status comports with RFRA’s requirement that “a person’s” rights be implicated. See 42 U.S.C. §2000bb-

1(a). Thus, we now determine whether Kraftwerk, as a family owned business with obvious ties to the

Amish religion, are protected under RFRA.

First, as a matter of statutory interpretation, Congress did not exclude for-profit corporations from RFRA’s protections. Although RFRA does not define “person,” the Dictionary Act is instructive here:

“In determining the meaning of any Act of Congress, unless the context indicates otherwise . . . the word[] ‘person’ . . . include[s] corporations, companies, associations, firms, partnerships, and . . . individuals.” 1 U.S.C. § 1. Additionally, the Supreme Court has affirmed the RFRA rights of certain corporate claimants. See Gonzales, 546 U.S. 418.

Indeed, at least some types of corporate entities are covered by RFRA. However, neither RFRA nor the Dictionary Act distinguishes between for-profit and non-profit corporations, and thus we must determine whether Congress intended to exclude for-profit corporations.

It is clear from the statutory exemptions present in Title VII, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-1(a), the

Americans with Disabilities Act, id. § 12113(d)(1), (2), and the National Labor Relations Act, that

Congress knows how to craft a corporate religious exemption, but chose not to do so in RFRA. If

Congress wanted to narrow the scope of protection under RFRA, it would have made it clear, as it is made clear in the above referenced statutes.

Furthermore, none of the cases to which we are directed by the government decide anything about for-profit entities’ religious rights. See Corporation of the Presiding Bishop of the Church of Jesus

Christ of Latter-day Saints v. Amos, 483 U.S. 327 (1987); Spencer v. World Vision, Inc., 633 F.3d 723 (9th

Cir. 2010); University of Great Falls v. NLRB, 278 F.3d 1335 (D.C. Cir. 2002). Indeed, the cases are undecided about for-profit status as it relates to religious corporations’ exemptions as persons under

Title VII and with regard to NLRB jurisdiction.

Based on the foregoing, there is no reason to think that Congress intended “person” under RFRA to mean anything other than its meaning in the Dictionary Act, which includes all corporations.

Second, some for-profit organizations may have Free Exercise rights as a matter of constitutional law. RFRA was drafted in response to Employment Division v. Smith, 494 U.S. 872 (1990), which eliminated the requirement that the government show a compelling need to apply a law burdening an individual’s Free Exercise rights. Id. at 882-84. The theory in Smith was that the Constitution permits burdening Free Exercise if that burden results from a neutral law of general application. Id. at 878-80.

RFRA sought to remedy the Smith holding and reinstate the stricter standard. There is no indication that

Congress intended to alter anything other than the above standard, including who can bring Free

Exercise claims.

29

Associations have Free Exercise rights. Roberts v. U.S. Jaycees, 468 U.S. 609, 618, 622 (1984)

(noting that courts have “recognized a right to associate for the purpose of engaging in those activities protected by the First Amendment—[including] . . . the exercise of religion”). The Free Exercise Clause extends to associations like churches, including those that incorporate. See, e.g., Church of Lukumi

Babalu Aye, Inc. v. City of Hialeah, 508 U.S. 520, 525 (1993) (holding that a “not-for-profit corporation organized under Florida law” prevailed on its Free Exercise claim).

Furthermore, as settled by the Supreme Court, individuals have Free Exercise rights with respect to their for-profit businesses. See, e.g., United States v. Lee, 45 U.S. 254 (1982); Braunfeld v. Brown, 366

U.S. 599 (1961).

Thus, individuals may associate and incorporate for religious purposes while retaining their Free

Exercise rights. Also, unincorporated individuals can operate in a for-profit manner and retain their Free

Exercise rights. These facts lead to the proposition that an individual who incorporates—even as the sole shareholder—retains Free Exercise protections. This is not merely about the protections of incorporating, i.e., limited liability and tax rates; religious organizations can incorporate and retain their

Free Exercise rights, even while receiving the protections of the corporate form.

A corporation that, at its core, operates from a religious foundation, as Kraftwerk does, should not be penalized for seeking to demonstrate to the marketplace that a corporation can succeed financially while adhering to religious values.

Kraftwerk, a closely held corporation operated under religious principles and run by the Krafts alone, has Free Exercise rights. We conclude that Kraftwerk qualifies as a “person” under RFRA.

We next determine whether the ACA places a substantial burden on Kraftwerk’s exercise of religion. See 42 U.S.C. § 2000bb-1(a)-(b).

Government action imposes a substantial burden on religious exercise if it: (1) “requires participation in an activity prohibited by a sincerely held religious belief,” (2) restricts participation in an activity motivated by such a belief, or (3) “places substantial pressure” on a religious adherent to join in conduct which is at odds with a sincerely held religious belief. Abdulhaseeb v. Calbone, 600 F.3d 1301,

1315 (10th Cir. 2010). For Kraftwerk, the third prong related to “substantial pressure” is the sole concern.

Our analysis under the third prong turns on the pressure the adherent feels to violate her religious beliefs. It does not concern whether the pressure is direct—forcing a prison inmate to choose between eating and violating his religious beliefs, as in Abdulhaseeb—or indirect, as is the case here, where Kraftwerk’s injury is based on decisions made by third parties, namely their employees. See

Thomas v. Review Board of the Indiana Employment Security Division, 45 U.S. 707 (1981); Lee, 450 U.S.

25.

30

The first step is to determine if the identified belief is sincerely held. Abdulhaseeb, 600 F.3d at

1314. If it is, the next step is to determine whether the government action substantially burdens

Kraftwerk’s exercise of its sincerely held religious beliefs.

The belief in question here is Kraftwerk’s conviction that life begins at conception. The extension of this belief is that a fertilized egg—an embryo—is alive, and that anything that intentionally causing the death of that embryo—like preventing implantation of an embryo in the uterine wall—is wrong. It is beyond question that this belief is sincerely held.

As to whether the government substantially burdens the exercise of Kraftwerk’s belief, it is difficult for us to see how the ACA’s effect on Kraftwerk could be considered anything less than substantial. To the extent that Kraftwerk provides a health plan, they would be fined extensively for every day they do not comply with the contraceptive coverage requirement. The penalties Kraftwerk would face number in the millions of dollars. If Kraftwerk chose not to carry a health plan, their penalties would still number in the millions of dollars, and they would face the added disadvantage of offering less attractive benefits to prospective employees. The only other option for Kraftwerk is to comply with the ACA, which violates Kraftwerk’s sincerely held belief that life begins at conception.

Kraftwerk has established a substantial burden as a matter of law.

RFRA requires the government to establish that forcing compliance with the contraceptive coverage requirement is “the least restrictive means of advancing a compelling interest.” O Centro, 546

U.S. at 423 (citing 42 U.S.C. § 2000bb–1(b)). This standard requires that we “look[ ] beyond broadly formulated interests justifying the general applicability of government mandates and scrutinize [ ] the asserted harm of granting specific exemptions to particular religious claimants.” Id. at 431.

Further, the compelling interest must be narrowly tailored: “RFRA requires the Government to demonstrate that the compelling interest test is satisfied through application of the challenged law ‘to the person’—the particular claimant whose sincere exercise of religion is being substantially burdened.”

Id. at 430. (quoting 42 U.S.C. § 2000bb–1(b)). Thus, the government must show with “particularity how

[even] admittedly strong interest [s]” “would be adversely affected by granting an exemption” to

Kraftwerk. Wisconsin v. Yoder, 406 U.S. 205, 236 (1972).

There are two interests asserted here: the interests in (1) public health and (2) gender equality.

These interests are important, but they are not compelling.

First, both interests are “broadly formulated interests justifying the general applicability of government mandates.” O Centro, 546 U.S. at 431. And the government offers almost no justification for not “granting specific exemptions to particular religious claimants.” Id.

Second, the interest here cannot be compelling because tens of millions of people are exempted from the ACA requirements. Indeed, those working for private employers with grandfathered plans and employers with fewer than fifty employees are exempt from the contraceptive coverage requirement.

As the Supreme Court has said, “a law cannot be regarded as protecting an interest of the highest order

31

when it leaves appreciable damage to that supposedly vital interest un-prohibited.” Lukumi, 508 U.S. at

547.

We thus conclude that the exemption for the millions of individuals here and the interests as formulated militate against finding that the stated interests qualify as compelling.

Even if the government had stated a compelling interest in public health or gender equality, it has not explained how those larger interests would be undermined by granting Kraftwerk a limited exemption. Kraftwerk objects only to covering four contraceptive methods out of twenty. Forcing

Kraftwerk to cover all twenty procedures when Kraftwerk is willing to cover sixteen of the twenty is far from using the least restrictive means to accomplish a government interest.

B.

The Krafts

For many of the reasons stated above as to Kraftwerk, we conclude that the Krafts as plaintiffs would likely succeed on the merits of their RFRA claim at trial. The Krafts, as the sole shareholders and owners of Kraftwerk, share the religious beliefs of their corporation. There can be no doubt that the ACA requirements of contraceptive coverage place a substantial burden on the Krafts’ Free Exercise of their religious beliefs. Further, the analysis of the government’s compelling interest and attempt to enforce the ACA by using the least restrictive means is no different merely because it applies to the Krafts rather than the Krafts’ company. The government has violated the Krafts’ Free Exercise rights by imposing on them the contraceptive coverage requirements of the ACA

VI.

Conclusion

Because Plaintiff is a person under RFRA, Plaintiff’s freedom to exercise religion has been substantially burdened by the ACA, and the government has failed to provide a narrowly tailored, compelling governmental interest for imposing such a burden, Plaintiff would likely succeed on the merits at trial. Thus, we reverse the district court’s holding regarding the first prong of the preliminary injunction standard, and remand for a determination of the satisfaction of the remaining factors.

IT IS SO ORDERED.

/s/ D. Jones

Judge David B. Jones

United States Appeals Court Judge,

United States Court of Appeals for the Twelfth Circuit

32

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

February Term 2014

Docket No. 12-05071983

Kathleen Strickland, Secretary of Health and Human Services, ET AL., Petitioners v.