Ch 6a. Strict and Intentional Torts

Chapter 6a: Strict Torts and Intentional

Torts

Ben Hoyt, Becky Nekula, Brett Falkner, Sam Straatmann, Leah Orf, Laura Lasher,

Chris Rimer, Michael Elliott, Tony Speno, and Bryce Jones

I.

Summary of Torts

A tort is a wrongful act that results in injury to a person, property, or one’s reputation.

The injured party can bring a civil lawsuit in order to obtain compensation for the wrongful act committed against them or their property. Civil torts are cases involving one private party against another while criminal cases involve the government confronting a defendant. The purpose of tort law is to reimburse the injured party, not punish the offender as in cases of criminal law. On the other hand, punitive damages may be given if the defendant’s actions were unruly or cruel.

Punitive damages will be examined later in this chapter.

Persons and business agents have the duty to not intentionally or negligently injure others.

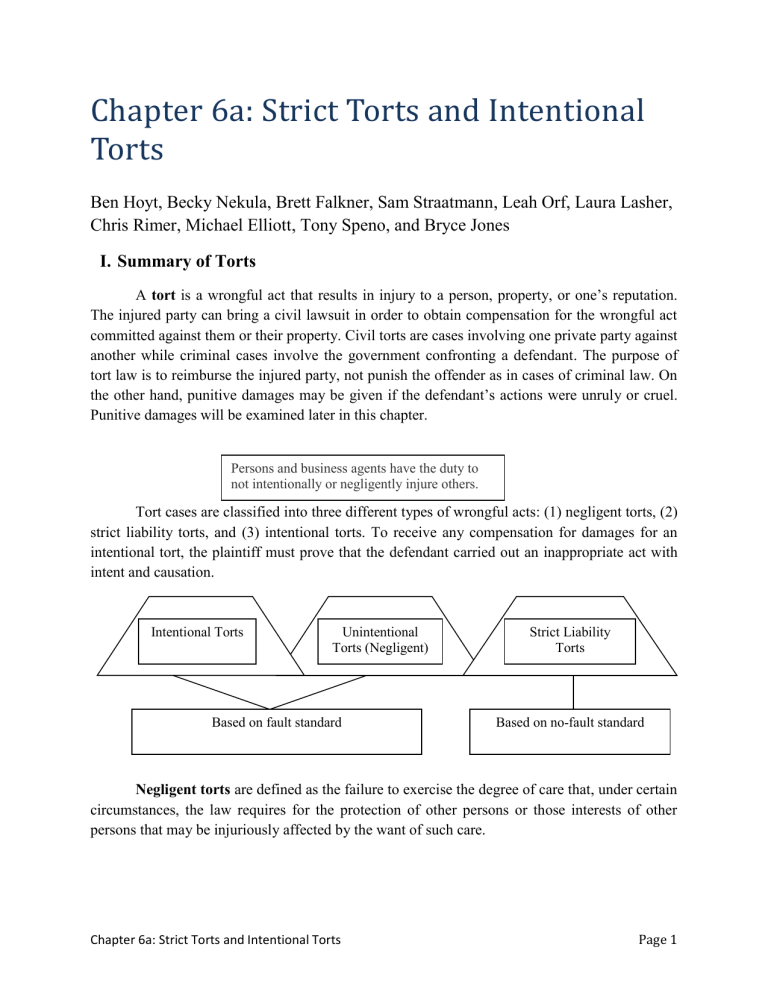

Tort cases are classified into three different types of wrongful acts: (1) negligent torts, (2) strict liability torts, and (3) intentional torts. To receive any compensation for damages for an intentional tort, the plaintiff must prove that the defendant carried out an inappropriate act with intent and causation.

Intentional Torts Unintentional

Torts (Negligent)

Strict Liability

Torts

Based on fault standard Based on no-fault standard

Negligent torts are defined as the failure to exercise the degree of care that, under certain circumstances, the law requires for the protection of other persons or those interests of other persons that may be injuriously affected by the want of such care.

Chapter 6a: Strict Torts and Intentional Torts Page 1

Example:

Jeff is playing around with a gun but does not know if it is loaded and pulls the trigger. If the gun goes off and injures Ben, Jeff has acted negligently towards Ben.

II.

Strict Liability

Strict liability is defined as a liability without fault. This means that fault does not have to be proven for the defendant to be found guilty, but the plaintiff does have to prove that the actions of the defendant caused the damage. In a strict liability case, the plaintiff does not need to prove intent, negligence, or recklessness by the defendant. Conversely, criminal liability in which requires the defendant to have performed the questionable act voluntarily.

Example:

Bob is a proud owner of a dog. The dog goes over to the neighbor’s house and digs up his yard. Bob would be strictly liable for the damage done by his dog because the dog trespassed onto the neighbor’s yard and caused the damage.

Strict liability is founded on the voluntary decision by the defendant to participate in a risky activity. When a corporation engages in such an activity, they can pass the costs of this liability on to consumers by charging higher prices. Strict liability applies when injuries result from any of the following activities: keeping dangerous animals, abnormally dangerous activities, or are caused by a defective product that is unreasonably dangerous.

The first classes imposed to strict liability were:

Owners of trespassing livestock

Keepers of naturally dangerous wild animals

The majority of activities do not apply to strict liability. To establish strict liability the following must be proven:

1.

Duty to make the activity safe

2.

Breach of that duty

3.

Injury of plaintiff due to that breach

4.

Damage to plaintiff’s person or property

Chapter 6a: Strict Torts and Intentional Torts Page 2

A.

Abnormally Dangerous Activities

Abnormally dangerous activities are activities with a risk of harm that cannot be removed by exercising reasonable care. Individuals or

1.

High degree of risk of harm to person, land, or chattels of others

2.

Likelihood of harm is great companies engaged in these activities will be strictly liable for any injuries caused by these activities. When

3.

Inability to eliminate risk by exercising reasonable care dealing with abnormally dangerous activities, fault is not considered and the risk of injury is treated as a cost of engaging in the activity.

4.

Whether activity is not a matter of common usage

5.

Inappropriateness of activity to where it is carried out

Example Activities:

Blasting Crop dusting Stunt flying

6.

Extent of value to the community over the dangerous attributes

Storage of large amounts of explosives or flammable gasses

The doctrine of strict liability for abnormally dangerous activities is derived from Rylands v. Fletcher . A party carrying on an abnormally dangerous business is strictly liable for damages. In order to determine whether an activity is abnormally dangerous, the Restatement (Second) of Torts, Section 520 lists six factors to be considered. (See box above) All of the factors are taken into consideration based on the particular case although all are not necessary for strict liability.

B.

Employer’s Liability for Employee Negligence

An employer has several duties to his or her employees:

1.

Warn of the hazards of employment

2.

Supervise activities

3.

Provide reasonably safe place to work

4.

Provide reasonably safe instrumentalities for work

The employer must instruct the employees in safe handling techniques for using products and equipment. If an employer breaches the duty to their employees, they are liable for the employees’ injuries caused by that breach. Workers’ compensation laws were enacted to impose liability on employers for injuries, occupational diseases, and deaths of employees, thus eliminating common-law defenses available to employers.

1.

Worker compensation is a no fault injury to worker

Chapter 6a: Strict Torts and Intentional Torts Page 3

2.

Employer is automatically liable when an employee harms another. Employer does not need to be at “Respondeat Fault Superior”. Employee may have to be at fault.

Under ordinary circumstances, according to tort law, the wrongdoer is the only one held liable. However, an exception occurs for an employer to be held liable for the torts of his or her employees if the employee was acting within the scope of his employment at the time of the injury. The scope of one’s employment refers to doing the employer’s business at the time of the tort. The reasoning for this exception is to ensure that the injured party be reimbursed in times that the employee is financially unable to pay. The employer will have to recognize this liability as an ordinary cost of doing business.

Example:

Allen, a truck driver, is employed by Jim’s Furniture Store. While delivering furniture, Allen negligently injures Mary. Mary has a cause of action against Allen and Jim’s Furniture Store.

Depending on the judgment, Mary can enforce it against either party or both until the entire amount is recovered.

C. Strict Liability for Products

Under strict liability, the manufacturer is held liable if the product it sells is defective, even if the manufacturer was not negligent. Strict liability only applies to those who regularly sell products. The idea of strict liability had been around as early as the 1930s, however, it was recognized as an individual tort in the court case Greenman v. Yuba Power Products, Inc.

in

1963.

Greenman v. Yuba Power Products, Inc.

A plaintiff was seriously injured while using a combination power tool that was defective.

The court said that the manufacturer would be strictly liable when the product sold, with the knowledge that it would be used without inspecting for defects, and causes injury due to a defect.

The court believed the purpose of strict liability for products would be to make sure that the manufacturers would bear the costs of defective products instead of the injured parties, who were helpless to protect themselves from the injuries.

In most states, the plaintiff must prove the following in order to recover under strict liability:

1.

The product was defective.

Chapter 6a: Strict Torts and Intentional Torts Page 4

2.

The product left the defendant in a defective condition.

3.

The product was unreasonably dangerous due to the defect.

4.

The defect was the proximate cause of injury.

Proving that a product was defective often requires the use of experts. A product may also be defective if the seller fails to warn the buyer of a hidden danger in the product that makes it defective. In a suit against the manufacturer, the custody of the product will need to be traced back to the manufacturer. Everyone in the distribution chain may be liable. However, the seller of the final product can still be strictly liable if the product left the seller in a defective condition. Finally, the injury from the defective product must have been foreseeable to the plaintiff. Therefore, recovery can be extended to others whose injury is reasonably foreseeable, such as family members or bystanders.

Unreasonably Dangerous

Products if Defective

Food

Drugs

Automobiles

Power Tools

Water Heaters

Intent - the purpose to commit a wrongful act having consequences that the one committing the act desires and believes or knows will occur.

The manufacturer has a defense, for example if the product is misused by the plaintiff which resulted in the injury. This misuse cannot be reasonably foreseen by the seller. Also, if the plaintiff knew of the dangerous defect, but used it anyway, they assumed the risk of injury and the manufacturer is no longer liable.

III. Intentional Torts

Intentional torts is a category of torts in which the defendant intends to do an act causing injury to the plaintiff.

Intent is a desire or goal to do something. The person committing the tort is liable for all reasonably foreseeable harm caused by the act.

Example of Intent :

Another form of intent would be

Jeff has a gun, points it at Robbie and pulls the trigger with the desire to kill Robbie or the knowledge that Robbie will be killed. Jeff intended to kill Robbie in this example.

recklessness. Recklessness is conduct whereby the person who is committing the act does not desire a harmful consequence but foresees the possibility and consciously takes the risk.

Recklessness, while being a type of intent, is separate from intent. Recklessness is sometimes called willful and wanton conduct. The defendant or person who committed the tort is aware of the risk or potential of harm created by a behavior but is indifferent as to whether or not it will occur.

Chapter 6a: Strict Torts and Intentional Torts Page 5

Example of Recklessness:

John likes to see how far he can throw heavy stones and he throws these stones near a busy intersection and hits a car. John acted recklessly if he had no intention to hit any cars, but was not absolutely certain that no one would be hurt. John would have known that the result was possible from his actions.

A. Intentional Torts Against Persons

1. Crimes with Victims

Each tort case has to be supported by a standard of proof known as preponderance of the evidence. This is not to be confused with the beyond-a-reasonable doubt burden found in criminal cases. If a plaintiff wins a tort case, they can receive either two kinds of damages from the defendant. The first is compensatory damages. These kinds of damages are recovered for the damage that the plaintiff suffered as a result of the defendant’s unjust actions. These damages could be for harms such as physical injuries, medical expenses, and lost wages or benefits.

Emotional distress, loss of privacy, or injury to reputation may also result in compensatory damages. The second kind of damages that a plaintiff can recover is punitive damages . Punitive damages are not intended to be given back to tort victims for their losses. They are intended to punish the defendant and discourage them, as well as others, from committing similar civil wrongdoings in the future. Punitive damages are not often imposed on the losing defendant in a tort case.

2. Assault and Battery

When a person’s personal security is attacked, a person has breached the duty to refrain from attacking another person. This tort is known as assault and battery and involves the physical touch of another person intentionally and unlawfully.

Battery is defined as an unwanted intentional physical contact or invasion of the victim’s freedom that is not permitted. It includes both harmful (causing bodily injury) and non-harmful contact in a way that may be offensive to that person or demeaning to their dignity. In order to be found guilty for battery, one has to have either the intent to cause harmful or offensive contact or the intent to apprehend someone in which there is a possibility that harmful or offensive contact may have occurred.

If John threatens to shoot Doug with a gun that he thinks is not loaded. However, the gun is loaded and he shoots Doug. John is liable for battery even if he did not intentionally mean to harm

Doug. If John intended to shoot Doug but instead shoots Aimee,

John would be liable to Aimee for battery.

Battery is not only limited to the original person that was threatened by the offender, but also to anyone harmed by the offender’s actions. This concept of transferred intent reveals that

Chapter 6a: Strict Torts and Intentional Torts Page 6

the person to whom the wrongdoing is done does not have to be the person to whom the harm was intended.

It is not necessary for the plaintiff to be aware of the crime at the instant it happened. For example, if the plaintiff is unconscious at the time of the tort he or she will still have a claim.

However, the battery charge cannot be applied if the plaintiff gave permission to the defendant.

Voluntary contact is, however, limited to the normal consequences of the activity.

Assault is causing fear of a harmful or offensive bodily contact. It is the threat to inflict immediate bodily injury, whereas battery is the actual physical contact, which typically follows the assault. Examples of an assault include threatening to strike someone, advancing toward someone with a violent expression, and pointing a weapon toward someone.

If John fires a shot at Doug which misses him, John is guilty of only an assault.

If the plaintiff wants to prove the tort of assault, they must have previously been aware of the defendant’s demeanor and believed to have been threatened by the defendant.

Like battery, the terms for intent are the same. In an assault case, it is not necessary to actually harm the victim. The plaintiff must show that they were worried about their own safety as a result of the defendant’s actions. The person being threatened must fear that the threat was to be carried out at the present time, rather than in the future. Threatening words are not usually grounds alone for assault charges unless they are accompanied by immediate acts that show intent to be carried out.

3. Intentional Infliction of Mental Distress

Intentional infliction of mental distress can be defined as wrongfully interfering with a person’s peace of mind by acting or using words to cause severe emotional distress to another person. The conduct must be extreme and outrageous for the tort to occur. In order for courts to rule in favor of the plaintiff on grounds of emotional distress, the conduct of the defendant must have been outrageous or beyond all boundaries of decency. It is also known as the tort of outrage.

Examples:

An employer’s liability for mental distress of an employee is heightened because of the employee being in a subordinate position to the employer.

Creditors and debt collection agencies can be held liable for intentional infliction of emotional distress for using tactics such as telephone calls at unreasonable hours, threatening to involve employers, and using abusive language.

Chapter 6a: Strict Torts and Intentional Torts Page 7

For years, courts did not recognize or allow judgment based only on emotional injuries.

The defendant must have committed one of the recognized torts. Only victims of assault, battery, and false imprisonment could recover damages for emotional injuries. The courts worried that if they recognized emotional distress as a separate tort there would be insignificant claims being processed. Most courts currently allow recovery of emotional injuries even if another tort is not in violation. This is due to the rise of confidence in the facts concerning emotional injuries. A final element of proof of suffering mental, emotional, or nervous distress is necessary. The determination of distress varies by state.

4. False imprisonment

False imprisonment is the interference with the victim’s freedom of movement. It is the intentional confinement of another person for a period of time without that person’s consent. It involves keeping someone trapped against his or her will using a physical barrier. It can also involve retaining possession of something owned by the victim that prevents them from moving freely.

Leah locks Laura in her office or prevents Laura from leaving her office by using force.

Adam prevents Nick from going onto property that Nick would otherwise be legally entitled to enter.

It is not necessary for there to be intent to restrain or harm the victim. In order for false imprisonment to be a legitimate case, the plaintiff has to have no other reasonable means to escape, such as another exit that would be well known or obvious. The plaintiff must also be aware of the imprisonment at the time it is occurring. No liability is put on the defendant if the plaintiff consents to the confinement.

Actual physical force is not a prerequisite to false imprisonment, which is exemplified in the case Parrott v. Bank of America National Trust & Saving Association .

A customer mistakenly reported a missing deposit at a branch of the defendant bank.

Parrott, the teller, was detained by the branch manager and inspector for several hours in order to obtain a confession and restitution of the money. After the customer reported that she had been mistaken and had found the deposit, Parrott brought this action to recover damages for false imprisonment. This temporary detention with threats of force by which

Parrot was deprived of liberty is false imprisonment. The use of actual physical force is not necessary. From the evidence, the jury reasonably inferred that the bank officials had not acted upon probably cause in detaining Parrott.

Merchant Protection Statutes are special statutes that have been instated to give store owners the right to stop, detain, and investigate anyone suspected of shoplifting. If the merchant

Chapter 6a: Strict Torts and Intentional Torts Page 8

reasonably believes that a person has stolen goods, they can restrain the suspect for a reasonable length of time and in a reasonable manner.

5. Defamation

Defamation is a false statement that wrongfully harms a person’s reputation, name, or character. The defendant’s statement must be both false and defamatory. The alleged defamatory statement must pertain to the plaintiff and hurt the reputation of the plaintiff or his or her standing in the community or deters others from associating with him or her. Defamatory statements do not generally apply to a group or organization unless the group is small enough that a certain member of that group can be distinguished as being affected by the statement.

The defense to a defamation case involves the plaintiff proving the truth. Privileges are granted in special cases because an individual’s right to reputation is not always the most important. An absolute privilege gives participants in judicial, legislative, and executive proceedings or from one spouse to another in private, protection against defamation suits. The purpose of absolute privilege is not to inhibit the freedom of expression which is necessary in each of these activities. Conditional privileges include any communication made in good faith on any subject in which the person communicating has an interest, or in reference to which he has a duty.

These privileges give the defendant certain entitlements and can be revoked if abused, mainly when the truth is disregarded even if the defendant is aware of the falsity.

Communications made to police or employers are considered to have conditional privilege.

In order for a defendant to be liable for defamation, a third party has to hear the false statement directly. It requires publication , not necessarily widespread, but the plaintiff and the defendant must have heard the statement. A publisher is liable for defamation but a mere distributor of the defamatory statement is not liable because they have no control over what is published.

An example of the distinction of liability between publishers and distributors would be:

If a writer for Hog Hunter Weekly publishes an article in the magazine expressing that Jeff Gordon dresses like a woman in his spare time and little Johnny sells that magazine to someone, the writer is the only one liable for defamation.

Defamation has two subcategories, libel and slander.

Libel is a malicious publication tending to injure the reputation of a person and expose him or her to public hatred, contempt, or ridicule. Generally, libel includes only printed defamation, such as pictures, signs, or statutes but now encompasses defamed statements made

Chapter 6a: Strict Torts and Intentional Torts Page 9

on television, radio or the Internet. Libel may be against the memory of someone who is dead or the reputation of someone who is alive. Slander is spoken defamation. In order to satisfy the publication requirement of slander, the defamed statement only needs to be communicated to another party other than the person defamed. This process of communication to a third party is called publication. Libel tends to be more permanent than slander. Also, since slander is spoken it can be harder to prove.

Plaintiffs can recover damages with no proof of actual injury under libel. Presumed or actual damages do not have to be proven to compensate for any harm that occurs. Some statements are defamatory on their face and presumed to cause damage. These statements are referred to as libel per se or slander per se if false statements include that the plaintiff:

1.

Committed a crime that could lead to imprisonment

2.

Has a vile disease

3.

Is guilty of serious sexual or professional misconduct

4.

Is not able to perform professionally

Defenses to Defamation

1.

Truth is always a defense. But the burden of proof is on the defendant to prove the truth of the statement. It is assumed that it is false unless it is proved to be true

2.

Absolute Privilege. Prosecutors, judges, and politicians typically enjoy an absolute privilege. Even if they lie, they cannot be sued.

Actual Malice - knowledge of a falsity or a reckless disregard for the truth

3.

Qualified Privilege. Reports to police or employers by citizens have a qualified privilege as long as they have reason to believe there is suspicious behavior. They cannot lie.

4.

Media Privilege. Newspapers, magazine, radio, TV, Internet

Reporting have a privilege when they report on public figures. Public figures are people already well known to the public. The media are not liable unless malice is shown. “Malice” means that the defamatory statements were lies or made with no good reason to think they were true (reckless disregard for the truth).

Disparagement of property includes the common-law torts of slander of title and slander of quality. Disparagement differs from defamation because it relates to property rather than persons. Disparagement is generally harder to prove than defamation. The extent of monetary damages must be proven as well as the falseness and maliciousness of the statement.

Chapter 6a: Strict Torts and Intentional Torts Page 10

Disparagement of title (slander of title) includes untrue statements that injure another’s interest in property. Slander refers to the type of law. The statement can be spoken or written.

The statement must be both false and malicious.

Example: Polly honestly but mistakenly believes that she is the owner of land that actually belongs to Parker. This challenge to Parker’s title causes Parker to sustain damage in not being able to dispose of the land. If Parker sues Polly for slander of title, the case will be dismissed. Polly’s conduct was not malicious.

Disparagement of quality (trade libels) is the publication of untrue statements of fact which claim that another person’s merchandise lacks the characteristics its vendors allege it has or that the product is inadequate for the purpose for which it is being sold. This statement must cause loss through impairment in the salability of the merchandise or property. The person who speaks the slanderous statement is liable for the loss due to the publication if it could have been reasonably anticipated. As with slander of title, the statement can either be spoken or written. In this type of slander, malice or honest mistake is immaterial. Truth, most of the time, is a defense of defamation and the burden of proof is on the defendant.

One privilege available in slander of quality is if someone is trying to protect a third party against loss. This person may express a reasonable belief that a product is inferior, especially where he is under a legal, moral, or civic duty to offer such protection such as a parent.

When it comes to a public figure who is written about in the media , proving defamation becomes more difficult because of actual malice and its presence. In the case of public officials or public figures, actual malice, reckless disregard for the truth, or falsity must be proven in cases of defamation. In order to prove actual malice, the public official or figure has to show that the statement made was false and reckless by clear and convincing evidence. In cases that do not involve public figures, on a preponderance of the evidence is required. The malice standard was introduced by the Supreme Court to dictate whether certain reports in the media are considered to be defamatory or libel statements. Media malice or reckless disregard for the truth is the intended wrongful reporting of the media in order to bring harm to a person’s reputation.

6. Invasion of Privacy

Invasion of privacy is made up of four separate torts. Each tort deals with a different meaning of privacy:

1.

Appropriation involves using the plaintiff’s name or likeness for financial gain without consent. A common example is through endorsing a product with the defendant’s business.

This kind of invasion of privacy looks at personal property right connection with a person’s identity and their exclusive right to control it. This has led to

Example:

Ben used a picture of Oprah on a brand of coffee without the consent from Oprah.

Chapter 6a: Strict Torts and Intentional Torts Page 11

the legal doctrine known as the right of publicity . This right allows celebrities, public figures and other entertainers to act against defendants that use the right holders’ name, likeness or identity without their consent.

2.

Intrusion is an unreasonable intrusion on a person’s solitude or seclusion.

This tort makes it illegal to intentionally intrude on the solitude or seclusion of another person as long as the intrusion would be highly offensive to a reasonable individual. This tort encompasses both physical and non-physical intrusion. There is no liability for looking at public records of a person.

Example of Physical Intrusion:

An illegal search of a person’s home or body or opening another person’s mail

Example of Non-Physical Intrusion:

Tapping phone lines or looking at private records, such as someone’s bank account

Ben used a picture of Oprah on a brand of coffee without the consent from Oprah.

This tort only applies where there is a reasonable expectation of privacy.

You are in a public place such as a mall and you take a picture of someone walking around. You are obviously not intruding on his or her solitude or seclusion. She is clearly in a public place, open to all of the public to see, so taking a picture would not be illegal according to this tort law.

Public disclosure of private facts protects private information from public disclosure.

Anytime someone publishes facts concerning someone else’s private life it can be an invasion of privacy. For public disclosure of private facts to apply, the published information must be highly offensive to a reasonable person. This tort law is based on the idea that the public has no legitimate right to know certain aspects about a person’s private life. Some examples of private facts that should not be disclosed are failure to pay debts, medical history, and sexual preferences. Even if the statements are true, public disclosure still violates the meaning of the tort of protecting private information.

This form of invasion of privacy potentially conflicts with the First Amendment. The courts are split as to how to deal with this problem. First, there is usually no liability for publicizing matters of public record or legitimate public interest. Second, public figures and public officials have no right to privacy concerning information that is reasonably related to their public lives. This is expressed every few years, especially during elections as negative ads are still a popular means of campaigning.

Chapter 6a: Strict Torts and Intentional Torts Page 12

3.

False light in the public eye protects a person from having false information distributed to the public. This tort states that a person cannot force someone into the public spotlight by attributing beliefs or personal characteristics to them that are inaccurate. In order for this tort to hold, the false light would have to be highly offensive to a reasonable person.

Example:

Signing a person’s name that is “pro-life” to a petition to increase abortion rights

7. Misuse of Legal Proceedings

The misuse of legal proceedings can be very detrimental to an individual. However, three intentional torts protect people against the harm that can result from someone wrongfully instituting legal proceedings. These are malicious prosecution, wrongful use of civil proceedings, and abuse of process.

The first of these torts, malicious prosecution , is meant to protect against wrongful initiation of criminal proceedings. Recovery for this wrong requires proof that the defendant caused the criminal proceedings to be initiated against the plaintiff without probable cause to believe that an offense has been committed, that the defendant did so for an improper purpose, and the criminal proceedings eventually were terminated in the plaintiff’s favor.

Wrongful use of civil proceedings is meant to protect against wrongful instituted civil suits. Overall it is very similar to malicious prosecution but applies to civil proceedings instead of criminal.

The third tort, abuse of process , is designed to protect against the initiation of legal proceedings for a primary purpose rather than the purpose for which such proceedings were designed. This tort protects against proceedings deviating from the actual content of the case to an unrelated action.

8. Misappropriation of Rights to Publicity

Although copyrights and the misappropriation of rights to publicity may seem similar, there is a distinct difference between the two. Copyrights specifically protect the creators work, whether intellectual or physical, from being copied without the creator’s consent.

Misappropriation of right to publicity protects the privacy or publicity rights of a person. The main difference between the right to publicity and a copyright is that copyright prohibits the copying of another’s work and misappropriation of right to publicity prohibits publicizing a person’s image without their consent.

Chapter 6a: Strict Torts and Intentional Torts Page 13

Example:

If a famous sport star’s face was used in advertising for an athletic shoe without his consent the sports player could sue for misappropriation of rights to publicity.

Before modern technology, the law was simple; a person’s identity was protected from commercial or public use. Now with modern technology the definition of the law has expanded.

It covers topics like look-alikes, sound-alike voices, nicknames, phrases, and former names. As time goes on, more and more topics will arise that will be covered by misappropriation of rights to publicity.

9. Fraud

Fraud is defined as intentional misrepresentation when one party deceives or takes advantage of another. Intent is a necessary element for fraud. For a situation to be considered fraud it must contain all of the following elements:

1) Misrepresentation of a material fact

2) Knowledge of falsity by the person making representation

3) Intent to induce the plaintiff’s reliance on the representation

4) Reasonable reliance by the plaintiff on the representation

5) Damage to the party due to the reliance

Bonnie is trying to sell her old beat up car to Clyde. She knows that the engine is a mess but it works at that point in time. She Tells Clyde that everything works fine with the car. Clyde not knowing anything about cars believes her and buys the car. The car breaks down two days after buying the car. Clyde can sue Bonnie for fraud.

In addition to the elements, in making a contract, if one party has an unfair advantage due to impaired mental capabilities, intoxication, or youth, the party in “normal” condition or the party initiating the contract is guilty of fraud. When a person or persons are guilty of fraud they are typically punished to a number of months in prison. The number of months varies depending on the type of fraud they committed.

B. Intentional Torts Against Property

1. Trespassing

Trespassing is the act of any unauthorized intrusion upon someone else’s personal property, usually land. It can be considered any unlawful or unwelcome presence on another’s land. Trespassing can be committed by doing a number of acts. This intrusion can include

Chapter 6a: Strict Torts and Intentional Torts Page 14

physically entering the property, causing another to enter the property, remaining on the land after it has been made clear to get off, invading the airspace above the land or the surface beneath it, and even causing some object to enter the land. Even if no harm is done to private property it is considered trespassing. Trespassing can be either innocent or willful. Innocent trespass is when a person is on another’s land by mistake or under the impression that he has a right to be there. It is still trespassing because the trespasser intends the consequences of their acts. Willful trespass occurs when a person knowingly goes on another’s land and knows that he

Example:

If you are walking home late at night and decide to cut through a few lawns for a short cut and in doing so you pass through a yard marked ‘Do not enter’, ‘Private property’ or something else of that nature. Even if you don’t see the sign due to darkness, you are still liable for trespassing onto that person’s property and you can be sued. should not be there. If trespass is willful the plaintiff is entitled to punitive damages which can include attorney’s fees.

Billy Bob has a well in his yard. He must make it safe by putting a cover over it or a fence around it so children can’t fall into the well. If he fails to do so and someone is hurt, he can be sued.

The intrusion does not have to be a human but anything put in motion by another person. If a person is allowed to be on the land but once on the land commits unlawful acts it is considered trespassing. For example a package delivery person can bring a package to the door but he may not enter the residence.

Trespassers are responsible for any damages they made to the property. They are also responsible for any damages that occurred while they were trespassing whether or not they intended for it to happen or if it was unexpected. Other than the trespasser being responsible for any damages that occurred while they were on private land, each state has their own rules as to any further consequences that the trespasser must endure.

Example: A person damages a fence while trespassing onto someone’s land.

When a person is injured on private/public property they may or may not be able to sue for compensation depending on the type of guest they are. There are three different types of guests and they include:

Trespassers (unwanted guests)

Chapter 6a: Strict Torts and Intentional Torts Page 15

Licensees (guests)

Invitees o Business Invitee - eg. customer o Public Invitee - eg. visitor at a state park

Trespassers or unwanted guests are responsible for harm caused to them while they were trespassing. They cannot sue the property owner. There are exceptions to this law though. A property owner cannot booby trap their land to cause intentional harm to trespassers. Also, if a property owner has an

“attractive nuisance”

they must make the attraction safe in case of a trespassing child.

Did You know?

In Missouri it is common for people in rural areas to put purple paint on trees that mark their property line to show trespassers they are unwelcome.

Licensees are people that a property owner invites or allows into her property. The property owner must inform guests about possible danger zones on their property or make the danger zone

Janitor Joe is mopping the floors in the entry way to the Student

Union Building and does not put up Caution Wet

Floors sign. Student

Sally walks through unknowing of the wet floors and falls and breaks her arm. She can sue the university. safe. If the property owner fails to do so then the licensees have the option of suing.

There are two types of invitees as stated above. A invitee is a customer to a business, like a shopper at Lowe’s or customer at a McDonalds. A public invitee business includes people on public grounds, for example, a person at a state park or a student at a university. The business or the government (party in-charge of the public ground) must warn any invitee about danger zones or they must make them safe to be around, similar to licensees. If the property owner doesn’t warn invitees about danger zones or make them safe then the invitee has the right to sue.

Property owners must notify trespassers that they are unwanted on the owner’s land. This notification may come in any form as long as it is obvious to trespassers. The most common way is to have a sign that says “No trespassing”.

The defense for any trespassing action is to show that the wrongful interference with another’s property rights was actually lawful. Another defense can be if the plaintiff neither owned, nor had the possession of, the property which the defendant was accused of wrongly taking or using. An example of this can be seen below:

2. Nuisance

The second tort relating to the interference with property rights is nuisance. Nuisance is any improper or indecent activity that causes harm to another person. There are two kinds of nuisance, private and public. For a private nuisance, a person’s use and enjoyment of his or her

Chapter 6a: Strict Torts and Intentional Torts Page 16

land would be interfering with other people. A public nuisance disturbs or interferes with the public in general. No physical trespassing is required, as most of the problems for this tort involve interferences such as odors, light, noise, smoke, and vibration. For a nuisance liability to exist, the interference must be substantial and unreasonable.

An example of this is in the court case Stephens v. Pillen:

Replevin and Conversion

When a property is damaged or stolen, the victim owner may sue the wrongdoer. There are two alternatives available to the owner, replevin or conversion. Replevin recovers property that is unlawfully detained and is founded on the claim that the defendant wrongfully withholds the property. In conversion the victim owner can sue for the monetary value of the property .

Conversion is the intentional exercise of control over the plaintiff’s property without his or her consent. Most often, the personal property in question is the plaintiff’s goods. Some examples of conversion include, acquisition of the plaintiff’s property, withholding possession of the plaintiff’s property, destruction or alteration of the plaintiff’s property, or using the plaintiff’s property. In every case, the wrongdoer intends to gain control over a certain property item.

Conversion is limited to very serious interferences with regard to property rights. Several factors are used to determine the seriousness of the offense including the following: the extent and duration of the withholding, the defendant’s motives, the amount of damage to the goods, and the inconvenience or harm suffered by the plaintiff. If it is a serious act of conversion, the defendant would be liable for the full value of the property.

An example of conversion can be seen in the case of Harlan v. Shank Fireproof Warehouse Co.

Harlan delivered personal property to Shank’s warehouse in

Indianapolis, Indiana. One month later, Shank shipped the goods to

Los Angeles, California and notified Harlan. The shipment was made without the authority, knowledge or consent of Harlan.

By shipping the goods without the approval of Harlan, Shank exercised an unauthorized control over the property which amounts to conversion.

Chapter 6a: Strict Torts and Intentional Torts Page 17

IV.

Conclusion

In this chapter we discussed how tort law imposes a duty on businesses and agents to not intentionally or negligently injure others. We discussed the different types of torts: intentional, negligent, and strict liability and broke down the different types of intentional torts related to business. Intentional torts against persons include assault and battery, intentional infliction of mental distress, false imprisonment, defamation, invasion of privacy, misuse of legal proceedings, misappropriation of rights to publicity, and deceit. Intentional torts against property are trespassing and nuisance.

Review Questions

1. What is the distinction between assault and battery?

2. What are the elements essential to intentional infliction of mental distress?

2. Explain the duty that an inviter owes to his invitee.

3. What is meant by the “attractive nuisance” doctrine?

4. What is the difference between absolute and conditionally privileged communication?

5. Nick contended that a defamatory statement is not slander unless it is made to the general public. Was he correct? Why or why not?

Original Works Cited

Gleim, Irvin N. "Tort Law." Business Law/Legal Studies. 7th ed. Gainesville, FL: Gleim

Publications, Inc., 2007. 97-124. http://www.gseis.ucla.edu/iclp/rftb.html - misrepresentation of rights to publicity http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/copothr.html- misrepresentation of rights to publicity http://encarta.msn.com/encyclopedia_761568375/Fraud.html - fraud http://law.jrank.org/pages/10898/Trespass-Trespass-Land.html

Additional Sources Used in Revision:

Blackburn, John D., Elliot I. Klayman, and Martin H. Malin. The Legal Environment of

Business. 3rd ed. Illinois: Irwin, 1988.

Chapter 6a: Strict Torts and Intentional Torts Page 18

Corley, Robert N., and Peter J. Shedd. Principles of Business Law. 14th ed. New Jersey: Prentice

Hall, 1989.

Howell, Rate A. An Introduction to Business Law: Principles and Cases. Illinois: The Dryden P,

1974.

Lavine, A. Lincoln. Modern Business Law. 2nd ed. New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1963.

Wyatt, John W., and Madie B. Wyatt. Business Law: Principles and Cases. 6th ed. New York:

McGraw-Hill, 1979.

Chapter 6a: Strict Torts and Intentional Torts Page 19