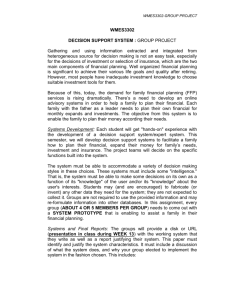

week_6_readings_maot

advertisement