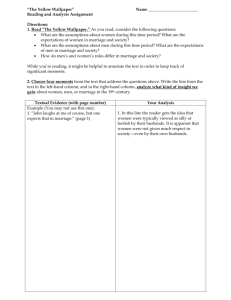

Engaging Communities to Confront Child Marriage in Bangladesh

advertisement

Engaging Communities to Confront Child Marriage in Bangladesh Executive Summary Penn-UNICEF Sumer Programme on Advances in Social Norms and Social Change Bangladesh is rated as the country with the highest incidence of child marriage globally, after Niger and Chad. Almost one third (32.3%) of women aged 20-24 were married by age 15 years according to MICs 2007. The same study indicates that at least 66% were married by age 18 years, despite the fact that 46% of these women had secondary education. Although figures are not available, many children are even married before the age of 15 years such that at least 5% of married women aged 20-24 years women had given birth by age 15 years. Internationally, child marriage is seen as a violation of the rights of children to education, the opportunity to develop to their fullest potential whilst at the same creating opportunities for exploitation, violence and abuse. Furthermore child marriage is recognized as depriving children of their childhood seen as a time for learning and play Child marriage in Bangladesh can be rated as a social norm (i.e. agreed rules of the game) for families across all ethnic groups of the country. The conditional preference for conformity is believed to be driven by the fact that everyone expects the bride price to increase as the girl gets older or that everyone believes/ thinks that the likelihood of sexual abuse increases exponentially from puberty onwards, especially for poorer households where several family members live in one-roomed huts. Dowry therefor exerts a strong economic pressure on parents to conform to early marriage. Dowry is also part of the script of how to interact with potential in-laws who will be taking over the responsibility of caring for your daughter. The factual beliefs include dowry (or groom price) that increase as girls get older (as the husband must be at least 5 years older); marriage protects girls from potential abuse (as delayed marriage increases the risk of loss of virginity and family honour); biological parents are seen as temporary caretakers of a girl (so investing in girls is seen as an economic loss); early marriage is believed to ensure many children (a belief that is at variance with current practice of just 2 children) as the country’s total fertility rate (TFR) is now at 2.3%. Overall the social expectations of what people think and expect of others reinforce the practice. The empirical expectation is that the majority of families marry their children off before age 18 years. Complementing this is the normative expectation that in each community everyone believes that others expect them to marry their daughters early to ensure chastity and protect family honour. From the day a Bangladeshi girl is born a family knows the script of how to behave concerning her upbringing. They also know how to conduct themselves when seeking suitors for their daughters. Dowry is part of the script that defines interaction with potential in-laws. At the same time the script of how children behave with regards to adults is known. All children, especially girls, are expected to respect and accept the decisions of the parents on when and who to marry. The schema, which is the more general mental representation of several scripts, inform how to conduct oneself (what to do and how to behave) regarding the upbringing and marriage of young girls. The drivers of child marriage in Bangladesh can be classified by the types of norms and categorized into either positive or negative. For example, the social norms exert a positive drive to be socially accepted and to be honoured and respected in one’s own community. On the other hand, the negative drive is the fear of social rejection, or of the family becoming a laughing stock and losing their place of honour in their society. In the case of moral norms, the positive driver is the warm glo of being a good parent that pays dowry to provide independent wealth and protection for a daughter whilst on the other side you have the guilt or troubling conscience that may result from seeing oneself as a bad parent. Although the Child Marriage Restraint act has been in existence since 1929, knowledge about its contents and the penalties associated with it is low. Nonetheless there is the fear of imprisonment or fines associated with this legal norm. In terms of the market norms, there is the aspiration of fathers to meet the needs of the family, including their daughters, which today requires a financial transaction of paying a groom price. Hence there is the real fear of the potential inability to pay the required groom price for an ‘older’ daughter. Child marriage in Bangladesh compares very closely with the Female Genital Cutting (FGC) scenario in many parts of Africa. There are common elements of (i) chastity and virginity linked to family honour and the fear of rejection by one’s society if s/he does not conform; (ii) inter-marriage between families and in some community; a strong issue of interdependence which means a family cannot decide if they want to stop the practice. On the Nance Webber other hand, differences can be linked to (i) market norms where, in the case of Child marriage, the pressure is immediate as the groom price increases as the daughter gets older, in the case of FGC, the marketability issue is portrayed in the aspiration of parents to marry of their daughters to relatively richer homes. In terms of age, the pressure for child marriage is concentrated within adolescence, especially between the ages of 15 and 18 years. With FGC, infibulation can be as early as a few months old to over 30 years depending on whether a woman decides to be cut immediately before or after marriage to increase acceptability by the groom’s family and their broader reference group. On another issue, FGC is controlled in large part by women, as mothers and grandmothers make all the arrangements and the ‘cutter’ is often a woman whereas child marriage is in the domain of fathers, uncles and male elders of the family. The men identify potential grooms and handle all cash or material transactions. UNICEF supports the government to implement a 3-pronged approach to tackle child marriage in Bangladesh. The Empowerment of Adolescents project provides both adolescent boys and girls with life skills including leadership and negotiating skills, in addition to knowledge on the basics of HIV/AIDs, sexual and reproductive health. This component also includes stipends (i. e.conditional cash transfers) to out-of schools girls for income generation, civic engagement and personal development. There is some evidence that once the girls start generating income the parents are more disposed to keep them longer at home or in school. Despite over 10 years of this programme, there is still some resistance to it implying that more needs to be done to broaden the base of the core group and ‘engage’ other community stakeholders to ensure resistance does not translate into parents and communities digging in their heels and marrying girls earlier. The 2nd component is enforcement of the law (1929 Child Marriage Restraint Act and 2011 Child Policy). A proposal is to support government adopt a more balanced approach that also profiles and publicizes ‘positive deviants’ , a much stronger way to let the nation know that over 33% of Bangladeshi married women marry after age 18 years. This is seen as a strong move to deconstruct what people think and believe others expect them to do regarding the marriage of their daughters. The 3rd component is Engaging Communities (EE) to reduce the incidence of child marriage in select unions of 20 UNDAF states by engaging members of the Ward Development Committees and the local Jamatt to facilitate peer group and community dialogues and collective community action against the practice. The EE component includes entertainment education using the animated cartoon character of Meena. There is a Meena film titled “Too Young to Marry” in which she uses the opportunity to bring new awareness on the harms of early marriage and benefits of delayed marriage. Meena is being broadcast through multiple channels – television, mobile cinema and in centres for out-of school children and has been popularised among the over 7 million children who either watch Meena on television or read Meena comic books and discuss the topics in school. A key factor of the theoretical framework to be applied is to start with the notion that legislation is simply not enough when attempting to address a social norm that is as entrenched as child marriage and strongly anchored around core values of chastity and family honour. Programming would also be on the basis that preferences and decisions are very interdependent and not individual or even limited to families. Thirdly would be to ensure that KAP studies, formative or other research probe for existence of social norms – what others think, do or expect. According to Biccheri, the following are key questions to ask: What do you think other people have done/will do? ; What do you think other people would think or do if someone was to do X? ; What are the people whose actions or attitudes you take into account when deciding whether to do X (the reference group)? The research will also ask counterfactual questions such as: what would happen if someone didn't do X? Activities of values deliberations are recognized as key to the framework. In the case of child marriage, the proposal is to start with small peer group dialogues to isolate the key values for each group/social network of fathers, religious leaders, traditional leaders, adolescent girls, adolescent boys, mothers etc.). Community dialogues will be gradually phased in based on guidance from the core group of change agents. Community dialogues will be key to achieve results of increased social learning, of social influence and more importantly to de-construct empirical and normative expectations by sharing actual data that delayed marriage is already a common practice in the country. An important learning point is the strategic importance of public declarations. In communities where the public oath is almost sacred, this event often signals a point of no return for all who participated and subscribed to the public commitment. During actual programming it would be very important to pay attention to who leads/champions the public declaration to ensure he has the trust of the community. This is where the new norm of marriage after 18 years is ‘declared’ and where everyone now subscribes to the new rewards and sanctions for compliance or deviance respectively. The theoretical framework accepts the role and place of the media and all social inter-personal networks, including the core group of change agents in actively promoting any recategorized values. In the case of child marriage, it may be worthwhile to try to promote a return to the original Nance Webber value of a ‘gift’’ for the family that will now be caring for your daughter as opposed to the costly transaction that dowry now represents. In conclusion, it is safe to state that Bangladesh is one country that has demonstrated that legislation, policy and resources are simply not enough to address entrenched social norms like child marriage. The advances in social norms and social change course has brought home the realisation that preferences and decisions in child marriage, as in FGC, are very interdependent and therefore cannot be addressed from the individual behaviour change perspective. An important learning point is that research and strategies must address what others think, do or expect of others, not just the usual KAP that focuses on knowledge, attitudes and practices. Nance Webber