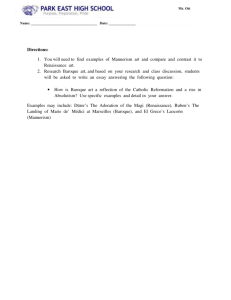

High Renaissance

advertisement

The High Renaissance In Memory of a Warrior Pope This is one of the structures as part of Julius II tomb. Originally a much larger planned project, Michelangelo reduced the project’s scale step-by-step until, in 1542, a final contract specified a simple wall tomb with fewer than one-third of the originally planned figures. This particular figure sums up the spirt of the entire tomb. Meant to be seen from below, and balanced with seven other massive forms related in spirit to it, the Moses now, in its comparatively paltry setting, does not have its originally intended impact. Michelagelo depicted the Old Testament prophet seated, with tablets of the Law under one arm and his hands gathering his voluminous beard. The horns that appear on Moses’s head were a sculptural convention in Christian art and helped Renaissance viewers identify Moses. Michelangelo , Moses Rome, Italy 1513-1515 The High Renaissance In Memory of a Warrior Pope Here, again, Michelangelo used the turned head, which concentrates on the expression of awful wrath that stirs in the mighty frame and eyes. The muscles bulge, the veins swell, and the great legs seem to begin to slowly move. If this titan ever rose to his feet, one writer said, the world would fly apart. To find such pent-up energy-both emotional and physical seated in a statue, historians must turn once again to Hellenistic statuary. Michelangelo , Moses Rome, Italy 1513-1515 The High Renaissance Struggling for Freedom of Expression Originally, Michelangelo intended for some twenty sculptures of slaves, in various attitudes of revolt and exhaustion, to appear on the tomb. One such figure is this, Bound Slave. Although conventional scholarship connected these statues with the Julius tomb, some art historians now doubt this. Despite many unanswered questions about these statues and their heritage the “slaves”, like David and Moses, represent definitive statements. Michelangelo made each body a different total expression of the idea of opression, so these sculpted human figures do not so much represent a concept, as in medieval allegory, but are concrete realizations of intense feelings. In Bound Slave, the defiant figure’s violent contrapposto is the image of frantic but impotent struggle. As noted earlier, many Hellenistic artists shared Michelangelo’s vision of the human form. The influence of the Laocoon group discovered in Rome in 1506, is especially clear in the struggling Bound Slave. Michelangelo based his whole art on his conviction that whatever can be said greatly through sculpture and painting must be said through the human figure. Michelangelo , Bound Slave Louvre, Paris 1513-1516 The High Renaissance A Mighty Christ on Judgment Day Michelangelo depicted Christ as the stern judge of the world- a giant whose mighty right arm is lifted in a gesture of damnation so broad and universal as to suggest he will destroy creation, Heaven and earth alike. The choirs of Heaven surrounding him pulse with anxiety and awe. Trumpeting angels, the ascending figures of the just, and the downward-hurtling figures of the damned crowd into spaces below. On the left, the dead awake and assume flesh; on the right demons, whose gargoyles masks and burning eyes revive the demons of Romanesque tympana, torment the Damned. Martyrs who suffered especially agonizing deaths crouch below the Judge. One of them, St. Bartholomew, who was skinned alive, holds the flaying knife and the skin, its face grotesque self-portrait of Michelangelo. Michelangelo Buonarroti, Last Judgement Vatican City, Rome, Italy 1534-1541 Image goes here Delete this text before placing the image here. The High Renaissance Stormy Weather Giorgione Da Castlefranco, The Tempest Galleria Dell’ Accademia, Venice. ca. 1510 Manifests the poetic qualities of natural landscape humans inhabit Lush landscape with stormy skies and lightning in the background. There is a woman nursing a baby and a man carrying a halberd (combination of a spear and a battle-ax) in the foreground. The painting’s subject is in debate. X-rays of the canvas show that the original canvas had a nude female standing where the man was placed. This leads scholars to believe that no definitive narrative exists, appropriate for a Venetian poetic rendering. Some scholars have suggested mythological narratives or historical events. Despite this uncertainty, the painting’s enigmatic quality lends it an intriguing air. Image goes here Delete this text before placing the image here. Mannerism Departing from Renaissance Ideals This is the dome painting of the Parma Cathedral. The artist showed his audience a view of the sky, with concentric rings of clouds where hundreds of soaring figures perform a wildly pirouetting dance in celebration of the Virgin’s Assumption. Versions of these creatures became permanent tenants of numerous Baroque churches in later centuries. Correggio was an influential painter of religious panels but his contemporaries expressed little appreciation for his art. Later, during the seventeenth century, Baroque painters recognized him as a kindred spirit. Though there is no direct reference to Mary’s ascension into the heavens in the bible, it has been consistently depicted in Christian art throughout the centuries. Antonio Allegri da Correggio Assumption of the Virgin, Parma, Italy 1530 Mannerism Discarding The Rules of Proportion This painting exhibits almost all of the stylistic features characteristic of Mannerism’s early phase in painting. The figures crown the composition, pushing into the front plane and almost completely blotting out the setting. Pontormo disposed the figural masses around the frame of the picture, leaving a void in the center, where High Renaissance artists had concentrated their masses. The composition has no clearly defined focal point and the figures seem randomly placed around the paintings edge. The ambiguous representation of space typifies the Mannerist style. The space seems too shallow to contain the action within it. The figures cast curious anxious glances in all directions. Athletic bending and twisting characterize many of the figures, with distortions of the head and body. Clashing colors add to the seeming dissonnce of the image. The painting represented a departure from the balanced, harmonious structured compositions of the earlier Renaissance. Jacopo da Pontormo, Descent from the Cross, Santa Felicità, Florence, Italy 1525 Mannerism An Allegorical Love Scene This painting manifests all the points made thus far about Manneristic composition. Bronzino demonstrated the Mannerist’s fondness for extremely learned and intricate allegories that often had lascivious (exciting sexual desires) undertones. Cupid is depicted fondling his mother, Venus, while Folly prepares to shower them with rose petals. Time, who appears in the upper right-hand corner, draws back the curtain to reveal the playful incest in progress. Other figures in the painting represent Envy and Inconstancy (unfaithfulness by virtue of being unreliable or treacherous). The masks symbolize deceipt. The picture seems to suggest that love, accompanied by envy and plagued by inconstancy is foolish and that lovers will discover its folly in time. But as in many Mannerist paintings the meaning here is ambiguous and interpretations of this painting may vary. The contours are structural and the surfaces smooth. Of special interest are the extremities, (hands, feet, etc.) for the Mannerists considered them carriers of grace and the clever depiction of them evidence artistic skill. Bronzino, Venus, Cupid, Folly, and Time (The Exposure of Luxury) National Gallery, London 1546 Mannerism Elegance and Grace This painting is Parmigianino’s best-known work. He acheived the elegance that was the principal aim of Mannerism. He smoothly combined the influences of Correggio and Raphael in a picture of exquisite grace and precious sweetness. The Madonna’s small oval head, her long slender neck, the unbelievable attenuation and delicacy of her hand, and the sinuous, swaying elongation of her frame are all marks of the aristocratic, gorgeously artifical taste of a later phase of Mannerism. On the left stands a bevy of angelic creatures, melting with emotions as soft and smooth as their limbs. On the right the artist included a line of columns without capitals- a setting for a figure with a scroll, whose distance from the foreground is immeasureable and ambiguous. Parmigianino, Madonna with the Long Neck, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence, Italy 1535 Mannerism A Mannered Portrait Most Mannerist painters achieved sophisticated elegance by portraiture. The subject is a proud youth -- a man of books and intellectual society rather then a lowly laborer or a merchant. His cool demeanor seems carefully affected, a calculated attitude of nonchalance toward the observing world. It asserts the rank and station but not the personality of the subject. The haughty poise, the graceful long fingered hands, the book, the furniture’s carved faces, and the severe architecture all suggest the traits and environment of the highbred patrician. Bronzino created a muted background for the subject’s sharply defined, asymmetrical Mannerist silhouette that contradicts his impassive pose. Bronzino, Portrait of a Young Man Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY 1530’s Mannerism Portraying Familial Intimacy Sofonisba Anguissola, Portrait of the Artist’s sisters and Brother 1555 Sofonisba Anguissola created much more relaxed portraiture than Bronzino. Anguissola used the strong contours, muted tonality, and smooth finishes. She introduced an informal intimacy of her own. This is a portrait of her family members. Against a neutral ground, she placed her two sisters and brother in an affectionate pose meant not for official display, but for private showing. The sisters, wearing matching striped gowns, flank their brother, who caresses a lap dog. The older sister (left) summons the dignity required for the occasion, while the boy looks quizzically at the portraitist with an expression of naive curiosity and the other girls diverts her attention toward something or someone to the painter’s left. Image goes here Delete this text before placing the image here. Anguissola’s use of natural poses and expressions; her sympathetic, personal presentation; and her graceful treatment of the forms did not escape the attention of her famous contemporaries. She captured ordinary life and put them into portraits. Mannerism A Problematic Painting of Christ Toward the end of Tintoretto’s life, his art became spiritual, even visionary, as solid forms melted away into swirling clouds of dark shot through with fitful light. In the Last Supper, the actors take part in a ghostly drama. They are insubstantial as the shadows cast by the faint glow of their halos and the flame of a single lamp that seems to breed ghostly spirits. Only the incandescent glow around the head of Jesus identifies him as he administers the Sacrement to his disciples. Tintoretto, Last Supper, San Giorgio Maggiore, Venice, Italy 1594 Image goes here Delete this text before placing the image here. The contrast with Leonardo’s Last Supper is both extreme and instructive. Their contrasts represents the direction Renaissance painting took in the 16 century, as it moved away from clarity of space and neutral lighting toward dynamic perspective. Later 16th Century Venetian Architecture An Architect Inspired by the Ancients The Villa Rotonda is not the typical of Palladio’s villa style. He did not construct it for an aspiring gentleman farmer, but for a retired monsignor who wanted a villa for social events. Palladio planned and designed Villa Rotonda, located on a hill top, as a kind of belvedere, without the usual wings of secondary buildings. It’s central plan with four identical facades and projecting porchesis both sensible and functional. Image goes here Delete this text before placing the image here. Andrea Palladio, Villa Rotonda near Vicenza, Italy 1568-1570