Alternative---Psycho Key---2NC

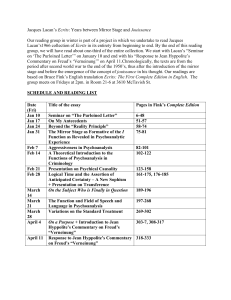

advertisement