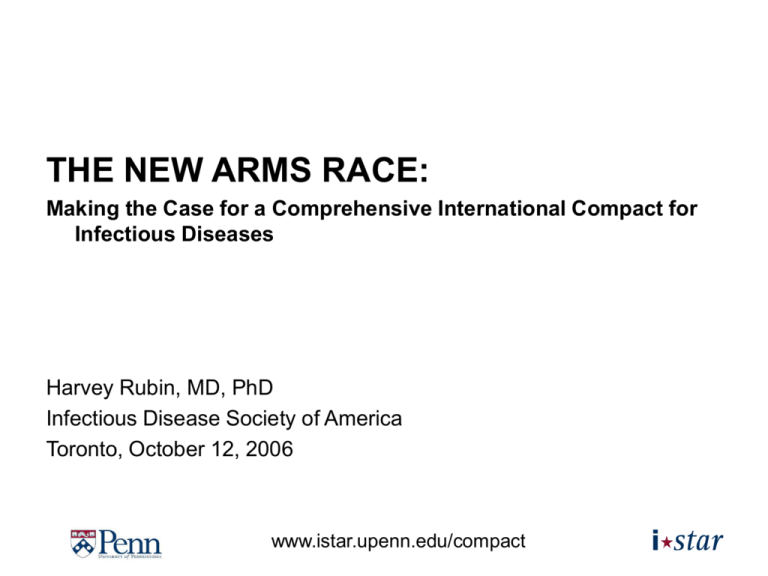

The Compact - University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine

advertisement

THE NEW ARMS RACE: Making the Case for a Comprehensive International Compact for Infectious Diseases Harvey Rubin, MD, PhD Infectious Disease Society of America Toronto, October 12, 2006 www.istar.upenn.edu/compact The problem Recognizing the impact of infectious diseases on national and international health, economic development and security, can a truly comprehensive agreement between states be developed that will limit and control known, newly discovered or deliberately created infectious diseases? www.istar.upenn.edu/compact The need is well documented • Emerging Infections: Microbial Threats to Health in the United States 1992, 2003, Institute of Medicine • The Global Infectious Disease Threat and Its Implications for the United States” 2000, unclassified report from the National Intelligence Council • The Darker Bioweapons Future 2003, unclassified CIA document analyzed the many benefits of modern molecular biology weighed against the danger that “the effects of engineered biological agents could be worse than any disease known to man.” • National Security Strategy: 2006, “Public health challenges like pandemics (HIV/AIDS, avian influenza) ... recognize no borders. The risks to social order are so great that traditional public health approaches may be inadequate, necessitating new strategies and responses. ...” (italics added). www.istar.upenn.edu/compact Dangerous assumption that an agreement exists www.istar.upenn.edu/compact Human Rights 1. International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (New York, 1966) 2. International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (New York, 1966) 3. Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (New York, 1966) 4. Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (New York, 1948) 5. Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (New York, 1984) 6. Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (New York, 2002) 7. International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of their Families (New York, 1990) 8. Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the involvement of children in armed conflict (New York, 2000) 9. Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the sale of children, child prostitution and child pornography (New York, 2000) www.istar.upenn.edu/compact Refugees 10. Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees (Geneva, 1951) 11. Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees (New York, 1967) Penal Matters 12. Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (Rome, 1998) 13. Agreement on the Privileges and Immunities of the International Criminal Court (New York, 2002) 14. Convention on the Safety of United Nations and Associated Personnel (New York, 1994) Terrorism 15. International Convention for the Suppression of Terrorist Bombings (New York, 1997) 16. International Convention for the Suppression of the Financing of Terrorism (New York,1999) 17. International Convention for the Suppression of Acts of Nuclear Terrorism (New York, 2005) www.istar.upenn.edu/compact Organized Crime and Corruption 18. United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime (New York, 2000) 19. Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children, supplementing the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime (New York, 2000) 20. Protocol against the Smuggling of Migrants by Land, Sea and Air, supplementing the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime (New York, 2000) 21. Protocol against the Illicit Manufacturing of and Trafficking in Firearms, Their Parts and Components and Ammunition, supplementing the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime (New York, 2001) 22. United Nations Convention against Corruption (New York, 2003) www.istar.upenn.edu/compact Environment 23. Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (Kyoto, 1997) 24. Rotterdam Convention on the Prior Informed Consent Procedure for Certain Hazardous Chemicals and Pesticides in International Trade (Rotterdam, 1998) 25. Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants (Stockholm, 2001) 26. Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety to the Convention on Biological Diversity (Montreal, 2000) Law of the Sea 27. United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (Montego Bay, 1982) and Agreement relating to the implementation of Part XI of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea of 10 December 1982 (New York, 1994) www.istar.upenn.edu/compact Disarmament 28. Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (New York, 1996) 29. Convention on the Prohibition of the Use, Stockpiling, Production and Transfer of Anti-Personnel Mines and on their Destruction (Oslo, 1997) Law of Treaties 30. Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (Vienna, 1969) Health 31. WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (Geneva, 21 May 2003) www.istar.upenn.edu/compact BUT NO COMPREHENSIVE PROGRAM FOR INFECTIOUS DISEASES www.istar.upenn.edu/compact What about the… • International Health Regulations (IHR) of the World Health Organization? • The Biological Weapons Convention (BWC)? www.istar.upenn.edu/compact THE SOLUTION We propose a comprehensive four-part International Compact for Infectious Diseases (the “Compact”) www.istar.upenn.edu/compact Treaties and Compacts: organizational benefits and drawbacks Compact Benefits: Treaty Benefits: Provides an international legal basis for enforcement. Quick to set up and provides a framework for action. Creates a body of durable “hard law” around an issue. Brings together a broad coalition of partners around a central issue. Draws on the power of governments to regulate and license within their jurisdiction Promotes voluntary compliance of laboratories, companies, etc. Compact Drawbacks: Treaty Drawbacks: Ratification is slow and may limit action on urgent issues. Enforcement relies on soft power and voluntary compliance. States may perceive enforcement clauses as an unacceptable burden. Soft power may prove ineffective during a health crisis. www.istar.upenn.edu/compact A Two-Pronged Approach Treaty (Identical in spirit to Compact) State State Compact State Eligible Parties: States Method of Participation: Ratification Academia Corporations NGOs Eligible Members: NGOs, academic institutions, corporations, independent research labs Method of Participation: Pledge of Membership and Voluntary Compliance www.istar.upenn.edu/compact Treaty and Compact: complementary systems • By providing parallel frameworks for different parties, the overall project will, over time, achieve the benefits of each. • Domestic partners who are signatories to the compact will pressure states to comply with the treaty. • Legitimacy and understanding of the overall system will be promoted through involvement of both state and non-state actors www.istar.upenn.edu/compact Compacts are effective governance structures 1) Human Rights • Inter-American Declaration of Human Rights (Organization of American States) • Helsinki Accords (Organization of Security and Cooperation in Europe) • Labor Rights Laws (International Labor Organization) • Sullivan Principles on Apartheid (Private Sector Active in South Africa) • McBride Principles (Private Sector Active in Northern Ireland) 2) Environment • Prior Informed Consent for Hazardous Chemicals in International Trade • Driftnet Fishing (UN General Assembly Series of Resolutions 1989-1992) • Antarctica Treaty Recommended Measures • Convention on Migratory Species (States were encouraged to create informal agreements within the treaty Memorandums of Understanding) 3) Arms Control/Disarmament • Nuclear Safety Measures (The International Atomic Energy Agency) • Suppliers Export Controls (Dual Use Technologies) • Landmines (Before the Ottawa Treaty) 4) Trade/Finance • Money Laundering (World Bank) • Standards Harmonization (International Standards Organization) • Environmental Soft Law Linkages with Trade (Asian Pacific Economic Community) www.istar.upenn.edu/compact The Compact: Part 1 Establish, maintain and monitor international standards for surveillance and reporting of infectious diseases using advanced information technology to ensure timeliness, interoperability and security www.istar.upenn.edu/compact The Compact: Part 2 Establish, maintain and monitor international standards for best laboratory practices www.istar.upenn.edu/compact The Compact: Part 3 Expand capabilities for the production of vaccines and therapeutics expressly for emerging and reemerging infections www.istar.upenn.edu/compact The Compact: Part 4 Establish, maintain and monitor a network of international research centers for microbial threats. www.istar.upenn.edu/compact Part 1 Establish, maintain and monitor international standards for surveillance and reporting of infectious diseases • States parties to the Compact would set up standard, secure computer architectures for biosurveillance information systems • Parties would define, and continuously refine, criteria for surveillance and reportable agents using latest information on endemic and emerging naturally occurring pathogens www.istar.upenn.edu/compact Epidemic and Pandemic Alert and Response • Epidemics and pandemics can place sudden and intense demands on health systems. They expose existing weaknesses in these systems and, in addition to their morbidity and mortality, can disrupt economic activity and development. • The world requires a global system that can rapidly identify and contain public health emergencies and reduce unneeded panic and disruption of trade, travel and society in general. • The revised International Health Regulations, IHR(2005) provide a global framework to address these needs through a collective approach to the prevention, detection, and timely response to any public health emergency of international concern. www.istar.upenn.edu/compact Epidemic and Pandemic Alert and Response (EPR) has six core functions • • • • • • Support Member States for the implementation of national capacities for epidemic preparedness and response in the context of the IHR(2005), including laboratory capacities and early warning alert and response systems Support national and international training programmes for epidemic preparedness and response Coordinate and support Member States for pandemic and seasonal influenza preparedness and response Develop standardized approaches for readiness and response to major epidemic-prone diseases (e.g. meningitis, yellow fever, plague) Strengthen biosafety, biosecurity and readiness for outbreaks of dangerous and emerging pathogens outbreaks (e.g. SARS, viral haemorrhagic fevers) Maintain and further develop a global operational platform to support outbreak response and support regional offices in implementation at regional level. www.istar.upenn.edu/compact From International Sanitary Conventions to Global Health Security: The New International Health Regulations David P. Fidler Chinese Journal of International Law (2005), Vol. 4, No. 2, 325–392 www.istar.upenn.edu/compact IHR issues • no mechanism for dispute settlement or enforcement • fundamental financial burden falls on developed states, not developing nations • IHRs do not increase access to therapeutics nor stimulate vaccine development From International Sanitary Conventions to Global Health Security: The New International Health Regulations David P. Fidler Chinese Journal of International Law (2005), 4, 325–392 www.istar.upenn.edu/compact Challenges for any surveillance and reporting system • trust between signatory nations and a willingness to share biosurveillance data • developing incentives to share data • creation of a common architecture for information systems requires common ontologies • developing and validating new algorithms and models of disease spread • consequences of non-reporting, or significantly underreporting the incidence of communicable diseases www.istar.upenn.edu/compact Technical solutions • integrate current initiatives into a national health IT strategy and federal architecture to reduce the risk of duplicative efforts • develop and adopt consistent interoperability standards • create enough flexibility to bring together disparate underlying IT languages and technologies to provide a common operating picture • generate the ability to accept multiple data formats used by agencies that provide the bio-surveillance information www.istar.upenn.edu/compact Technical solutions • generate the ability to feed information back to the originating agencies providing bio-surveillance information in a format each agency can accept • identify data flows that will evolve during the developmental process • allow the methods of analysis to evolve and adapt as new data become available or existing data sets are improved • know and evaluate the effectiveness of the current underlying algorithms, methods, and structures for biosurveillance data analysis. www.istar.upenn.edu/compact Governance solutions The Compact will use “soft” methods to encourage reporting and discourage noncompliance • Compliance status will be made public • Parties not reporting or under-reporting disease incidence will have lower priority to – vaccines and therapeutics – research done through the Compact www.istar.upenn.edu/compact Part 2 International Standards for Best Laboratory Practices • Bio-safety: at risk – Laboratory personnel – Local public health – National and international public health • Unavaoidable linkage to bio-security www.istar.upenn.edu/compact Example of International Standards for Best Laboratory Practices Survey of 300 Asian life scientists engaged in research with over 60 different infectious agents and/or toxins. 1. examine the policies and standards employed to advance biosafety and biosecurity 2. understand the practices, equipment and facilities used by these researchers 3. examine existing regulations in the context of the infectious pathogens they study 4. identify and address gaps in the development and implementation of policies related to laboratory biosafety and biosecurity Advanced China Hong Kong Japan Korea Singapore India Emerging Pakistan Thailand Taiwan Malaysia Developing Indonesia Cambodia Vietnam Bangladesh Philippines Sri Lanka www.istar.upenn.edu/compact Results of the Sandia survey Most of the laboratories profiled in the study perform risk assessments as the antecedent to instituting a biosafety plan. These plans, along with a laboratory’s biosecurity practices are highly influenced by each country’s national government. Five of the top nine infectious agents identified by respondents should be studied under biosafety level (BSL) 3 conditions, however almost two-thirds of researchers state they are working only with BSL 2 practices. www.istar.upenn.edu/compact Another example of best practices: recent publication of 1918 Pandemic Influenza Virus Papers “The 1918 virus and recombinant H1N1 influenza viruses were generated using the previously described reverse genetics system (8, 14). All viruses containing one or more gene segments from the 1918 influenza virus were generated and handled under highcontainment biosafety level 3 enhanced (BSL3) laboratory conditions in accordance with guidelines of the National Institutes of Health and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (15).” www.istar.upenn.edu/compact “1918 Flu and Responsible Science” “I firmly believe that allowing the publication of this information was the correct decision in terms of both national security and public health.” Science Editorial Vol. 310, 7 October 2005 Philip A. Sharp www.istar.upenn.edu/compact “The 1918 flu genome: Recipe for Destruction” “This is extremely foolish. The genome is essentially the design of a weapon of mass destruction.” New York Times Op-Ed October 17, 2005 Ray Kurzweil and Bill Joy contributors www.istar.upenn.edu/compact Best Lab Practices Model Compact / Treaty Organization Private Sector Signatory State Certification Body Public/Private Universities Research Labs State Labs University Labs 1. The Compact develops and adopts best laboratory practices with input from signatories. 2. Signatories set up internal certification bodies responsible for ensuring compliance with BLPs. 3. Signatories submit annual reports to expert panel within Compact verifying compliance with BLPs. 4. Signatories that do not comply with BLPs suffer reduced access to compact institutions and data, and their non-compliance in publicized. www.istar.upenn.edu/compact Part 3 Expansion of capabilities for the production of vaccines and therapeutics expressly for emerging and reemerging infections 1. An innovative solution for the limited base of manufacturing and distribution of therapeutics and vaccines has to be achieved 2. Government as well as large, multi-national pharmaceutical concerns and the biotechnology industry need to engage in a commitment to expand the manufacturing base 3. Manufacturing contracts would be awarded to the countries or organizations with the most compelling offer, including commitments to assurance of continuity of supply and operations, safety, security and infrastructure. 4. The signatories to the Compact would agree to fund the efforts sufficiently, perhaps representing a percentage of their GDP, thereby pooling the resources of many nations to create assured supplies of drugs and vaccines on a global scale as well as for specific local use. www.istar.upenn.edu/compact Challenges 1. The market for therapeutics and vaccines in the developing world is too small to attract serious commercial research investment 2. Even in the developed world, vaccine markets generally suffer from high up-front costs relating to research and regulation, and uncertain demand over time 3. Vaccines against potential biological weapons will suffer from high demand uncertainties and, should a bioterror event occur, may be requisitioned rather than purchased at market price 4. The enterprise requires high levels of transparency, oversight and acceptance of international standards for licensure 5. Incentives and enforcement must be considered www.istar.upenn.edu/compact Editorial September 6, 2006 Vaccine Futures One of the big reasons that companies don’t try to develop vaccinations for poor-country diseases is that they fear there won’t be a market for them. So what if rich countries promised to buy them? That’s the very simple idea behind a new plan to entice companies into making vaccines for illnesses that mostly kill poor people, like malaria and tuberculosis. The program will be discussed by finance officials from wealthy nations at a meeting in Rome tomorrow. It works like this: Rich countries commit to pay a specific amount to help poor countries buy a guaranteed supply of a needed, effective vaccine. The subsidy would allow the manufacturer to recoup its investment and earn a profit. The company agrees that after it has received the pledged amount, it will sell to poor countries cheaply. A panel of experts recommended that the idea be tried first to promote a vaccine against pneumococcal disease, which kills about 1.6 million people a year, making it the leading vaccinepreventable cause of death. AIDS is making this kind of infection more common, and the bacteria are increasingly resistant to the antibiotics used to treat them. In the last few years, researchers have tried several novel financing ideas. Many combine government and charitable financing with industrial know-how. This idea would complement the others. The Bush administration has been reluctant to join international financing mechanisms. But it has no reason not to jump on this plan, which will benefit American companies and is a private-sector, market-driven program that pays only for success. www.istar.upenn.edu/compact Potential Financial Models 1. Advance Market Commitments 2. International Finance Facility for Immunization (IFFIm)- bond mechanism to pay for vaccines borrowing operating funds in the international capital markets over 10 years, expecting a triple-A credit rating 3. International drug purchase facility (IDPF) – French plan to levy tax on airline tickets www.istar.upenn.edu/compact Among the many benefits 1. The Compact equitably spreads the high cost of manufacturing and distribution of drugs and vaccines across a group of nations. 2. It creates a structure with which to develop incentives for large pharmaceutical corporations to undertake the development of vaccines and therapeutics. 3. It provides the mechanism to achieve the common goal of providing the world with standardized and authenticated agents. 4. It will address the legal issues of international pharmaceutical licensing. www.istar.upenn.edu/compact Part 4 Establishment, maintenance and monitoring of a network of international research centers for microbial threats. 1. The research centers should have a permanent faculty and staff as well as visiting fellowships and studentships. 2. The lasting positive impacts of international research centers include fostering long-term relationships between scientists, establishing a culture of research responsibility and serving as the nucleus for safe applications of interdisciplinary sciences globally. 3. The example of the "Rice Institutes" funded by the Rockefeller Foundation for fifteen years and sustained by the Consultative Group in International Agricultural Research, provides an example. RICE BIOTECHNOLOGY: Rockefeller to End Network After 15 Years of Success. Dennis Normile Science 19 Nov. 1999:286, 1468 – 1469 1. www.istar.upenn.edu/compact The Compact: incentives and enforcements • These recommendations are made with full awareness of the inherent legal, political, diplomatic and economic challenges of multilateral compacts. • We believe that a major strength of linking the production and distribution of therapeutics and vaccines with biosafety, biosecurity and improved access to and participation in research programs creates a global incentive of compassion, maximization of human health and welfare and economic and scientific development. • Furthermore, the Compact uses both incentives and penalties to create a cohesive international body that does not challenge sovereignty, but pools resources. • Non-participation by any given state would lower its priority to receive the cost benefits of therapeutics and vaccines. • The non-participating state would have lower priority in the research center. www.istar.upenn.edu/compact Benefits: the whole is greater than the sum of its parts 1. Provide access to specific therapeutics and vaccines that are relevant to the signatories. 2. Provide access to cheaper and more highly standardized therapeutics and vaccines. 3. Ensure better quality control of vaccines, therapeutics and diagnostics in the developing world, leading to fewer expired or counterfeit agents. 4. Provide access to and participation in high-level research. 5. Provide developing and developed states with a voice in the direction of research and development. www.istar.upenn.edu/compact Benefits: the whole is greater than the sum of its parts 6. Distribute the costs and risks of research and development across a number of countries 7. Provide more complete datasets on emerging infections and potential pandemics. 8. Create a more competitive market for vaccine and therapeutic development targeting diseases of relevance to signatory nations. 9. Enhance and enable human health and well being, economic development, and basic biological research. www.istar.upenn.edu/compact Global Collaborators Martin J. Blaser, M.D., Frederick H. King Professor of Internal Medicine, Chair, Department of Medicine, Professor of Microbiology, New York University School of Medicine William W. Burke-White, Assistant Professor of Law, University of Pennsylvania, Member, Government of Rwanda, Constitutional Commission, Member, International Criminal Tribunal for Yugoslavia, The Hague. Arturo Casadevall, MD, PhD. Professor, Medicine, Microbiology, & Immunology, Chair, Department of Microbiology & Immunology, Leo and Julia Forchheimer Professor of Microbiology & Immunology Abdallah S. Daar D.PHIL(OXON), FRCP(LON), FRCS(ENG.&ED.), FRCSC, FRS(C). Professor of Public Health Sciences and of Surgery at the University of Toronto, Director of the Program in Applied Ethics and Biotechnology, co-Director of the Canadian Program on Genomics and Global Health and Director of Ethics and Policy at the McLaughlin Centre for Molecular Medicine. David Franz, DVM. PhD, Senior Biological Scientist, Midwest Research Institute and Director of the National Agricultural Biosecurity Center at Kansas State University Sir Lawrence Freedman, Professor of War Studies and Vice Principal (Research), King's College London Malcolm Gillis, PhD. Zingler Professor of Economics and University Professor, Rice University Manfred S Green MD, PhD. Director, Israel Center for Disease Control , Professor of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine in the Sackler Faculty of Medicine at Tel Aviv University Dr. Green’s views do not necessarily reflect the views of the Israel Ministry of Health. www.istar.upenn.edu/compact Phillip A. Griffiths, PhD. Professor, School of Mathematics, Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton NJ. Former Director, Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton. J. Tomas Hexner, MBA. Director Science Initiative Group. Cambridge, Massachusetts Chung W. Kim, PhD. Director Emeritus, Korea Institute for Advanced Studies, Emeritus Professor, Physics and Astronomy, Johns Hopkins University Stuart B. Levy M.D., Professor of Molecular Biology and Microbiology and of Medicine and the Director of the Center for Adaptation Genetics and Drug Resistance at Tufts University, School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts Dr. Adel Mahmoud M.D. PhD., President of Merck Vaccines (retired). Erwann Michel-Kerjan, PhD., Managing Director of the Risk Management and Decision Processes Center at the Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania Peter A. Singer, MD, MPH, FRCPC , Co-Director of the Canadian Program in Genomics and Global Health; Senior Scientist at the McLaughlin Centre for Molecular Medicine; Professor of Medicine at University of Toronto and University Health Network; and a Distinguished Investigator of the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. www.istar.upenn.edu/compact Next steps 1. • • • • 2. 3. Complete the legal, business and research cases by engaging the pharmaceutical industry the information technology industry NGOs Academia Feedback and suggestions from you, log on to: www.istar.upenn.edu/compact Present plans to the appropriate national and international government agencies www.istar.upenn.edu/compact www.istar.upenn.edu/compact Thanks to the University of Pennsylvania students • • • • • Adrian Arroyo Dr. Jian Shin Teh Joanna Johnston Daniel Milich Jon Stott www.istar.upenn.edu/compact “ We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard, because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one which we intend to win…” John F. Kennedy Rice University September 12, 1962 www.istar.upenn.edu/compact