Jordan Kulp

HCL

Mrs. Martin

2 May 2012

Dropping the F Bomb; Feminism in Metamorphosis

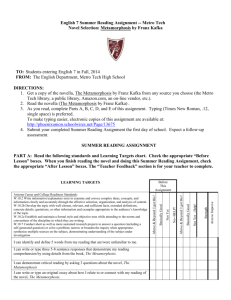

Nina Pelikan Straus wrote “Transforming Franz Kafka’s Metamorphosis”, in this article

she argued that the traditional discussions of Kafka’s Metamorphosis were predominately male

and disciplined. She felt that adding in a feminist view would add to the complexity of the novel,

bringing in views that were yet to be discussed. “As a prophet of the complexities engendered by

“the woman question,” Kafka’s text, fortunately, no longer delivers its message only to

(alienated) men” (Straus 140). When looking at the novel again through a feminist view, there

are traces of power struggles between the two genders, as well as sexual frustrations and

complexes, and self-empowerment and discovery.

A lot of Nina’s article specifies on the power struggles in the novel between male and

females. For instance, the women in the novel are not expected to do any work and just be house

maids, which is a typical sexist household; men do the work and get the money; but once Gregor

is altered forever, the power shifts to the sister. “..mark the moment of her rite of passage into an

independent, if harsh, sphere of womanhood that separates her from the world of her father(s).

Having passed through stages of submission and sympathy, through the burden of symbolically

mothering a being that resembles a sickly and degenerate child, and having replicated her

brother’s stages of maturation and professionalism (for she now has a job), Grete initiates her

liberation” (Straus 138). In the criticism, Nina mentions how in the novel, Grete takes away

Gregor’s pornographic picture expressing her complete and total dominance over him because

sexuality is a natural tendency for humans and now he has been stripped of his last remains of

normality. It is as if the two have switched roles in society, now Grete is dominant and

pronounced, while her brother is helpless and voiceless like a typical household “bitch” (Straus

130).

Mentioned before, Gregor keeps a photograph of a woman he doesn’t know in his room.

Going off the assumption that he is doing this to fill a void of not having a woman or a life

outside of his parent’s house and work, turning into a vermin in a shell can symbolize how he

feels trapped which would also be why he can’t speak. He is on his back and is moving in

vulgar-like movements, and this can symbolize that he is sexually frustrated (not to mention the

goo all over his face and stomach). “Gregor’s transformation is regression; his male sexuality is

neutered and infantilized” (Straus 135).

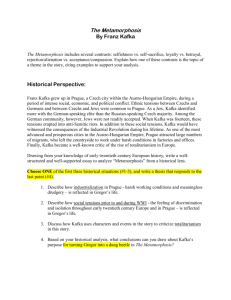

Along with sexual frustrations, Nina mentions something about a Oedipal complex; she

states “Kafka’s final solution for Gregor involves both oedipal and female complexes; it

represents the urge to kill the potential father figure who is himself, as well as the urge to

become woman. Such a reading of Metamorphosis, through what might be called a biographical

gender analysis, suggests that the tale is not merely an oedipal fantasy but more broadly a fantasy

about a man who dies so that a woman may empower herself” (Straus 138). Through sexuality,

even the confusing and unnatural sense in metamorphosis, there is a sense of self-empowerment.

Throughout the story, every character becomes self-aware in some way. For example, the

parents become aware that they are dependent on Gregor, and that they need to be more

independent to survive. Gregor realizes he has lost everything that made him himself as he took

on the responsibility for everyone. Grete realizes she, although a woman, can gain power and

become independent. Each person’s revelation thrives off each other’s “For Kafka there can be

no change without an exchange, no flourishing of Grete without Gregor’s withering; nor can the

meaning of transformation entail a final closure that prevents further transformations” (Straus

132).

Work Cited

Straus, Nina Pelikan. “Transforming Kafka’s Metamorphosis.” Signs: Journal of Women in

Culture and Society 14.3 (1989):651-67. Rev. 1994