KATHE KOLLWITZ AND MOTHERHOOD Jessica Pennock Art

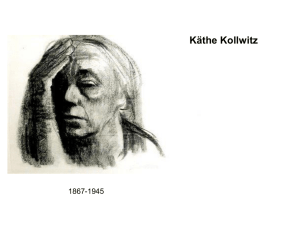

advertisement

1 KATHE KOLLWITZ AND MOTHERHOOD Jessica Pennock Art, Feminism, and History 9 December 2013 2 The theme of motherhood is one of the oldest in art history. Images of the Virgin and Infant Son are most readily associated with this theme, and date to the early middle ages. In dealing with the theme of motherhood, printmaker Kathe Kollwitz was revolutionary in her imagery, exploring deeply conceptual themes of motherhood in relationship to death, loss, and war; a stark contrast to conventional images that came before her. To understand Kollwitz’s conception of the motherhood motif, it is necessary to develop an understanding of her work’s form and content in relationship to the accepted historical and contemporary images of mother and child, as well as the historical context in which she lived and worked. Incredibly, Kollwitz’s life spanned the German Empire, the Social Democratic Weimar Republic, and the Nazi dictatorship. She was born in 1867 in the German province of Prussia. Her family was nonconformist in both politics and religion, and Kathe was exposed to ethical and justice concerns as well as socialist values from an early age. Her artistic education began at age 13 with a teacher in her hometown, and staring at age 17, she studied in Berlin and Munich. Kathe’s education focused primarily on the medium of printmaking (including etching, soft ground, aquatint, dry point, lithography, and other, more experimental methods), and though she tried painting on occasion, she almost always abandoned the painting to explore the imagery in her preferred medium (Prelinger). In 1981, at age 24, Kollwitz married a boyhood friend of her brother, Karl Kollwitz. The couple moved to Berlin, where they lived for the remainder of their lives together. Karl was a doctor specializing in women’s health. The building they lived in was not only their home; it also housed Karl’s clinic and Kathe’s studio. This was critical for the development of form and content in Kathe’s work, as she interacted daily with the working-class women that visited the clinic, often using them as models for her prints (McCausland). 3 In 1892, Peter, the couple’s first son, was born, followed in 1896 by her second son. It was around this time that Kollwitz began exhibiting her work and gaining credence as a professional. Up until this point, much of Kollwitz’s work was influenced by her political and social position. She was, at the time her family was beginning in particular, very concerned with empathy for the poor, the identity and daily struggle of working class women, and themes of political injustice. Scenes often depicted riots, workers rising against oppression, and other various states of protest and action, as shown in her 1902 “Outbreak.” When World War I began in 1914, the theme of motherhood increased in focus, especially after Peter, her eldest, was killed in the war, and with few exceptions, she produced no new works depicting violent revolution. Towards the end of her life, she rejected completely the subject matter of her early work, proclaiming her previously held view of war was a “utopian notion blind to the deadly and corrupt side of revolution” (Melanie). In 1919, Kollwitz was the first woman elected to membership in the Prussian Academy of Art, and she became a professor. Having been given a large studio to accommodate the work, she began sculpting more readily, and around this time also began printing primarily in woodcut, preferring it over etching for its graphic quality and immediate ability to relay visual information (Moorjani). In 1928, she became the director of graphic arts (the printmaking program) in the Academy. However, her public career came to a halt when Hitler rose to power in 1933, forcing Kollwitz to resign from the Academy and from teaching. In addition, with Hitler having declared avant garde art “degenerate,” Kollwitz was forbidden to exhibit and all her work was removed from public collections. She continued to create her work more privately, remaining a productive and active artist until age 70, when she died in 1945 (Jean Owens). 4 In looking specifically at Kollwitz’s imagery of mother and child, it is evident that her perspective of motherhood is much different than traditional artistic renditions. Motherhood as a social construct underwent significant change in European society in the centuries before Kollwitz’s life. Until the end of the Enlightenment, children were viewed as burdens, their care needs were passed off to wet-nurses and governesses, and the images created reflect these ideas, the conventions of the Virgin and her Infant Son, and the accepted artistic practices of the time. Towards the end of the Enlightenment, the social view of motherhood shifted, and the images created show sentimental scenes of mother and child, typically in domestic spaces, such as Marguerite Gerard’s “The Piano Lesson.” Accordingly, in the 19th century, mothers became more domestic, responsible for the nurturing, training, moral development and early education of their children, and the mothers represented in artworks from the time are appropriately termed “happy mothers,” as they joyfully and virtuously serve their families (Buettner). Though mother and child figures became more intimate with one another since the traditional Madonna and Child, Kollwitz’s images create an even more immediate intimacy between the figures not seen in earlier exploration of the theme (Buettner). In stark contrast to traditional paintings such as “The Piano Lesson,” Kollwitz’s imagery of mother and child generally contain intensely emotional figures, often tortured by suffering, with contorted, exaggerated, and disproportionate features. These figures are often weaved together in tight circular compositions, so much so that it is sometimes difficult to determine the boundaries between one figure and another. Some critics have compared the structure of her compositions to the womb, suggesting that the mothers in the images are “attempting to take back inside them the child to whom they gave birth” in an effort to protect them from the pain of the world (McCausland). “Mother with Dead Child,” created in 1903, is one such image. “Mother with 5 Dead Child” was Kollwitz’s first non-narrative version of the nude mother and child, and one of her earliest explorations of the theme. Interestingly, she used herself and her then 7 year old Peter as models for this work. In fact, Kollwitz often used herself as a model for her more traumatic prints, and preferred other models for the very few tender images of mothers she created (McCausland). Other formal choices also impact the differences between these two works of art. In contrast to traditional images, Kollwitz’s mothers were rarely grounded in a domestic space, and in fact, are often centrally located on an ambiguous background, if any at all, giving the figures deeper psychological depth. In contrast, traditional Madonna and Child icons were generally placed within the context of the divine, whether through gold colors, alters or iconic structures, or with angels and other holy beings present (Collins). This serves to further differentiate the function of Kollwitz’s images against traditional, religious icons. Similarly, the medium Kollwitz preferred greatly affects the viewer’s impressions of the content. As previously mentioned, prints allowed Kollwitz to be unburdened in the way that paint could not, which was crucial for the representation of her subject (Mills). Painting is naturally associated with a certain historical motif, including the Virgin and Child images, and in dealing with such traditional subject matter, prints were a much more effective medium for Kollwitz. “The Mothers,” a part of the 1920’s War series, and is an example of another key way Kollwitz’s mothers typically interacted with their children. It depicts a group of women sheltering or encircling children with strong, dominant arms. In similar images, towering mothers are seen protecting their sons, and metaphorically, the youth of an entire nation at war (Moorjani). 6 Finally, the horror of death and loss are often used in conjunction with motherhood in Kollwitz’s work, as seen in the two images shown, titled “Death Claims a Woman” and “Death and the Woman.” The incorporation of death as a literal third figure suggests a much different conceptual meaning than the images of mother and child created by Kollwitz’s contemporaries, for example, Morisot and Cassatt, as well as traditional holy family paintings (Buettner). The holy family paintings that gained importance and prevalence at the end of the middle ages included Jesus as an infant (or at least proportional to a small child, though occasionally possessing more adult features), Mary (also referred to as Madonna, the Virgin, etc.), and either St. Joseph, the child’s father, or St. Anne, Mary’s mother (Collins). They function as a religious symbol, bringing God and man together in scenes of majesty and virtue. In these images, Christ’s or God’s presence among humans is very plain, in the same way that death is often made to be a literal third figure among the families in Kollwitz’s work. Death as a third figure brings a different element of spirituality to Kollwitz’s work; rather than being vehicles for God’s divine plan, the figures in Kollwitz’s work are experiencing immediate anxiousness and concern for their children, and Kollwitz is advocating for those in suffering, empathizing with the grieving. In Kollwitz’s regularly kept journal, she often speaks of her connection spirituality and prayer as achieved through grieving and associated with death. For example, on July 15, 1915, just under a year after losing Peter, Kollwitz writes, “It is said that prayer ought to be coming to rest in God, a sense of uniting with the divine will. If that is so, then I am—sometimes—praying when I remember Peter,” and “When I feel him in the way which I want to make outwardly visible in my work, then I am praying” (Kollwitz). During Kollwitz’s life, Prussia’s infant mortality rate of 25% was the highest of any German province, and demands of agricultural work made it necessary for women to return to working in the fields almost immediately after delivery 7 (Buettner). With the death of a child an ever present threat, and with sons torn from families to go to war, Kollwitz explored imagery that is not only very relevant to a grieving nation, but also incredibly active and immediate. Certainly, Kollwitz was aware of the changing meaning of motherhood in light of her nation’s political and social circumstances. Whether her work is interpreted as a product of her own grief, or of another force, it is clear that the women in her work are experiencing something very different from those in traditional paintings, a perspective for which Kollwitz has been and will continue to be recognized. 8 References Buettner, S. "Images of Modern Motherhood in the Art of Morisot, Cassatt, Modersohn-Becker, Kollwitz." Women's Art Journal 7, no. 2 (1987): 14-21. JSTOR. Collins, Bradley. "Dysfunctional Holy Families: Loss, Rage, and Desire in Renaissance Images of the Virgin and Child." Notes in the History of Art 27, no. 2 (2008): 10-17. JSTOR. Jean Owens, S. "The Kollwitz Konnection: before the women's movement Kathe Kollwitz wasn't hailed as a "successful" artist. Jean Owens Schaefer traces her reception in America between 1900-1960." Women's Art Magazine 62, no. 10 (January 1995). Academic OneFile. Kollwitz, Hans, ed. The Diary and Letters of Kaethe Kollwitz. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1988. McCausland, E. “Kathe Kollwitz.” College Art Association 9, no. 2 (1937): 20-25. JSTOR. Melanie, H. “Art as Expression: Kathe Kollwitz.” School Arts 93, no. 6 (February 1994): 33. Academic OneFile. Mills, J. F. “Portrait of the Artist as Printmaker.” Criticism 2, no. 4 (1960). JSTOR. Moorjani, A. “Kathe Kollwitz on Sacrifice, Mourning, and Reparation: An Essay in Psychoaesthetics.” MLN 101, no. 5 (December 1986): 1110-1134. JSTOR. Prelinger, E. “Kathe Kollwitz.” Print Quarterly 10, no. 2 (June 1993): 197-199. JSTOR. Schulte, R. “Kathe Kollwitz’s Sacrifice.” History Workshop Journal 41 (1996): 193-221. JSTOR.