Indian Airlines HR Problems

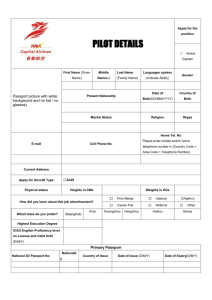

advertisement

-1- Indian Airlines HR Problems “There could scarcely be a more undisciplined bunch of workers than IA’s 22,000 employees.” - Business India, January 25, 1999. FLYING LOW Indian Airlines (IA) – the name of India’s national carrier conjured up an image of a monopoly gone berserk with the absolute power it had over the market. Continual losses over the years, frequent human resource problems and gross mismanagement were just some of the few problems plagued the company. Widespread media coverage regarding the frequent strikes by IA pilots not only reflected the adamant attitude of the pilots, but also resulted in increased public resentment towards the airline. IA’s recurring human resource problems were attributed to its lack of proper manpower planning and underutilization of existing manpower. The recruitment and creation of posts in IA was done without proper scientific analysis of the manpower requirements of the organization. IA’s employee unions were rather infamous for resorting to industrial action on the slightest pretext and their arm-twisting tactics to get their demands accepted by the management. During the 1990s, the Government took various steps to turn around IA and initiated talks for its disinvestment. Amidst strong opposition by the employees, the disinvestment plans dragged on endlessly well into mid 2001. The IA story shows how poor management, especially in the human resources area, could spell doom even for a Rs 40 bn monopoly. BACKGROUND NOTE IA was formed in May 1953 with the nationalization of the airlines industry through the Air Corporations Act. Indian Airlines Corporation and Air India International were established and the assets of the then existing nine airline companies were transferred to these two entities. While Air India provided international air services, IA and its subsidiary, Alliance Air, provided domestic air services. In 1990, Vayudoot, a low-capacity and short-haul domestic airline with huge long-term liabilities, was merged with IA. IA’s network ranged from Kuwait in the west to Singapore in the east, covering 75 destinations (59 within India, 16 abroad). Its international network covered Kuwait, Oman, UAE, Qatar and Bahrain in West Asia; Thailand, Singapore and Malaysia in South East Asia; and Pakistan, Nepal, Bangladesh, Myanmar, Sri Lanka and Maldives in the South Asian subcontinent. Between themselves, IA and Alliance Air carried over 7.5 million passengers annually. In 1999, the company had a fleet strength of 55 aircraft - 11 Airbus A300s, 30 Airbus A320s, 11 Boeing B737s and 3 Dorniers D0228. In 1994, the Air Corporation Act was repealed and air transport was thrown open to private players. Many big corporate houses entered the fray and IA saw a mass exodus of its pilots to private airlines. To counter increasing competition IA launched a new image building advertisement campaign. It also improved its services by strictly adhering to flight schedules and providing better in-flight and ground services. It also launched several other new aircraft, with a new, younger, and more dynamic in flight crew. These initiatives were soon rewarded in form of 17% increase in passenger revenues during the year 1994. However, IA could not sustain these improvements. Competitors like Sahara and Jet Airways (Jet) provided better services and network. Unable to match the performance of these airlines IA faced -2severe criticism for its inefficiency and excessive expenditure human resources. Staff cost increased by an alarming Rs 5.9 bn during 1994-98. These costs were responsible to a great extent for the company’s frequent losses. By 1999 the losses touched Rs 7.5 bn. In the next few years, private players such as East West, NEPC, and Damania had to close shop due to huge losses. Jet was the only player that was able to sustain itself. IA’s market share, however continued to drop. In 1999, while IA’s market share was 47%, the share of private airlines reached 53%. Unnecessary interference by the Ministry of Civil Aviation was a major cause of concern for IA. This interference ranged from deciding on the crew’s quality to major technical decisions in which the Ministry did not even have the necessary expertise. IA had to operate flights in the North-East at highly subsidized fares to fulfill its social objectives of connecting these regions with the rest of the country. These flights contributed to the IA’s losses over the years. As the carrier’s balance sheet was heavily skewed towards debt with an equity base of Rs 1.05 bn in 1999 as against long term loans of Rs 28 bn, heavy interest outflows of Rs 1.99 bn further increased the losses. IA could blame many of its problems on competitive pressures or political interference; but it could not deny responsibility for its human resource problems. A report by the Comptroller and Auditor General of India stated, “Manpower planning in any organization should depend on the periodic and realistic assessment of the manpower needs, need-based recruitment, optimum utilization of the recruited personnel and abolition of surplus and redundant posts. Identification of the qualifications appropriate to all the posts is a basic requirement of efficient human resource management. IA was found grossly deficient in all these aspects.” ‘FIGHTER’ PILOTS? IA’s eight unions were notorious for their defiant attitude and their use of unscrupulous methods to force the management to agree to all their demands. Strikes, go-slow agitations and wage negotiations were common. For each strike there was a different reason, but every strike it was about pressurizing IA for more money. From November 1989 to June 1992, there were 13 agitations by different unions. During December 1992-January 1993, there was a 46-day strike by the pilots and yet another one in November 1994. The cavalier attitude of the IA pilots was particularly evident in the agitation in April 1995. The pilots began the agitation demanding higher allowances for flying in international sectors. This demand was turned down. They then refused to fly with people re-employed on a contract basis. Thereafter they went on a strike, saying that the cabin crew earned higher wages than them and that they would not fly until this issue was addressed. Due to adamant behaviour of pilots many of the cabin crew and the airhostesses had to be offloaded at the last moment from aircrafts. In 1996, there was another agitation, with many pilots reporting sick at the same time. Medical examiners, who were sent to check these pilots, found that most of these were false claims. Some of the pilots were completely fit; others somehow managed to produce medical certificates to corroborate their claims. In January 1997, there was another strike by the pilots, this time asking for increased foreign allowances, fixed flying hours, free meals and wage parity with Alliance Air. Though the strike was called off within a week, it again raised questions regarding IA’s vulnerability. April 2000 saw another go-slow agitation by IA’s aircraft engineers who were demanding pay revision and a change in the career progression pattern[1]. The strategies adopted by IA to overcome these problems were severely criticized by analysts over the years. Analysts noted that the people heading the airline were more interested in making peace with the unions than looking at the company’s long-term benefits. Russy Mody (Mody), who joined IA as chairman in November 1994, made efforts to appease the -3unions by proposing to bring their salaries on par with those of Air India employees. This was strongly opposed by the board of directors, in view of the mounting losses. Mody also proposed to increase the age of retirement from 58 to 60 to control the exodus of pilots. However, government rejected Mody’s plans[2]. When Probir Sen (Sen) took over as chairman and managing director, he bought the pilot emoluments on par with emoluments other airlines, thereby successfully controlling the exodus. In 1994, the IA unions opposed the re-employment of pilots who had left IA to join private carriers and the employment of superannuated fliers on contract. Sen averted a crisis by creating Alliance Air, a subsidiary airline company where the re-employed people were utilized. He was also instrumental in effecting substantial wage hikes for the employees. The extra financial burden on the airline caused by these measures was met by resorting to a 10% annual hike in fares. (Refer Table I) TABLE I IMPACT OF STAFF COST HIKE IN FARE INCREASE (%) Date of fare increase 25/07/1994 1/10/1995 22/09/1996 15/10/1997 1/10/1998 Source: IATA-World Air Transport Statistics Impact (%) 16.22 25 36 13.44 8.8 Initially, Sen’s efforts seemed to have positive effects with an improvement in aircraft utilization figures. IA also managed to cut losses during 1996-97 and reported a Rs 140 mn profit in 1997-98. But recessionary trends in the economy and its mounting wage bill pushed IA back into losses by 1999. Sen and the entire board of directors was sacked by the government. In the late 1990s, in yet another effort to appease its employees, IA introduced the productivity-linked scheme. The idea of the productivity linked incentive (PLI) scheme was to persuade pilots to fly more in order to increase aircraft utilization. But the PLI scheme was grossly misused by large sections of the employees to earn more cash. For instance, the agreement stated that if the engineering department made 28 Airbus A320s available for service every day, PLI would be paid. This number was later reduced to 25 and finally to 23. There were also reports that flights leaving 30 - 45 minutes late were shown as being on time for PLI purposes. Pilots were flying 75 hours a month, while they flew only 63 hours. Eventually, the PLI schemes raised an additional annual wage bill of Rs 1.8 bn for IA. It was alleged that IA employees did no work during normal office hours; this way they could not work overtime and earn more money. Though experts agreed that IA had to cut its operation costs. To survive the airline continued to add to its costs, by paying more money to its employees. (Refer Table II). The payment of overtime allowance (OTA) which included holiday pay to staff, increased by 109% during 1993-99. It was also found that the payment of OTA always exceeded the budget provisions. Between 1991-92 and 1995-96, the increase in pay and allowances of the executive pilots was 842% and that of non-executive pilots was 134%. Even the lowest paid employee in the airline, either a sweeper or a peon, was paid Rs 8,000 – 10,000 per month with overtime included. TABLE II INCREASE IN STAFF COSTS Per Staff cost Staff cost Total Effective No. of employee as Year (in Rs expenditure fleet employees cost (in percentage bn) (in Rs bn) size mn) of total -4operational expenditure 19932.85 22182 0.13 20.75 94 1994- 3.74 22683 0.16 22.59 95 (31.18%)* 1995- 5.71 22582 0.25 26 96 (52.59%) 1996- 7.10 22153 0.32 29.29 97 (24.35%) 1997- 8.17 21990 0.37 32.21 98 (15.03%) 1998- 8.75 21922 0.39 34.31 99 (7.12%) Source: IATA-World Air Transport Statistics * Figures in brackets indicate increase over the previous year. # Excludes 4 aircraft grounded from 1993-94 to 1995-96 as well Allied Services Ltd. from 1996-97 to 1998-99. 15% 54 19% 58 25% 55 26% 40 27% 40 28% 41 as 12 aircraft leased to Airline In 1998, IA tried to persuade employees to cut down on PLI and overtime to help the airline weather a difficult period; however there efforts failed. Though IA incurred losses during 1995-96 and 1996-97 and made only marginal profits during 1997-98 and 1998-99, heavy payments were made on account of PLI. A net loss of Rs 641.8 mn was registered during the period 1995-99. PLI payments alone amounted to Rs 6.66 bn, during the same period. According to unofficial reports, arrears to be paid to employees on account of PLI touched nearly Rs 7 bn by 1999. Over the years, the number of employees at IA increased steadily. IA had the maximum number of employees per aircraft. (Refer Table III). It was reported that the airline’s monthly wage bill was as high as of Rs 680 mn, which doubled in the next three years. There were 150 employees earning above Rs 0.3 mn per annum in 1994-95 and the number increased to 2,109 by 1997-98. The Brar committee attributed this abnormal increase in staff costs to inefficient manpower planning, unproductive deployment of manpower and unwarranted increase in salaries and wages of the employees. TABLE III A COMPARISON OF VARIOUS AIRLINES Name of Airlines Number of No. of aircraft in employees fleet ATKm[3] ATKm per (in Million) Employee Employees per aircraft Singapore Airlines 84 13,549 Thai Airways International 76 24,186 6546.627 270678 318 Indian Airlines 51 21,990 2113.671 398204 431 Gulf Air 14418.324 1064161 161 30 5,308 1416.235 245831 177 Kuwait Airways 22 5,761 345.599 92853 261 Jet Airways 3,722 1094.132 49756 196 19 Source: IATA-World Air Transport Statistics Analysts criticized the way posts were created in IA. In 1999, Six new posts of directors were created of which three were created by dividing functions of existing directors. Thus, in place of 6 directors in departments’ prior April 1998, there were 9 directors by 1999 overseeing the same -5functions. There were 30 full time directors, who in turn had their retinue of private secretaries, drivers and orderlies. The posts in non-executive cadres were to be created after the assessment by the Manpower Assessment committee. But analysts pointed that in the case of cabin crew, 40 posts were introduced in the Southern Region on an ad-hoc basis, pending the assessment of their requirement by the Staff Assessment Committee. Another problem was that no basic educational qualifications prescribed for senior executive posts. Even a matriculate could become a manager, by acquiring the necessary job-related qualifications & experience. Illiterate IA employees drew salaries that were on par with senior civil servants. After superannuation, several employees were re-employed by the airline in an advisory capacity. According to reports, IA employed 132 retired employees as consultants during 1995-96 on contract basis. With each strike/go-slow and subsequent wage negotiations, IA’s financial woes kept increasing. Though at times the airline did put its foot down, by and large, it always acceded to the demands for wage hikes and other perquisites. TROUBLED SKIES Frequent agitations was not the only problem that IA faced in the area of human resources. There were issues that had been either neglected or mismanaged. For instance, the rates of highly subsidized canteen items were not revised even once in three decades and there was no policy on fixing rates. Various allowances such as out-of-pocket expenses, experience allowance, simulator allowance etc. were paid to those who were not strictly eligible for these. Excessive expenditure was incurred on benefits given to senior executives such as retention of company car, and room air-conditioners even after retirement. All these problems had a negative impact on divestment procedure. This did not augur well for any of the parties involved, as privatization was expected to give the IA management an opportunity to make the venture a commercially viable one. Freed from its political and social obligations, the carrier would be in a much better position to handle its labor problems. The biggest beneficiaries would be perhaps the passengers, who would get better services from the airline. QUESTIONS FOR DISCUSSION: 1. Analyze the developments in the Indian civil aviation industry after the sector was opened up for the private players. Evaluate IA’s performance. Why do you think IA failed to retain its market share against competitors like Jet Airways? 2. IA’s human resource problems can largely be attributed to its poor human resource management policies. Do you agree? Give reasons to support your stand.