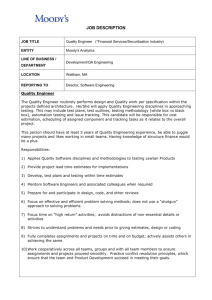

Business and Society Stakeholders Ethics Public Policy

advertisement

Case 1: Moody’s Credit Ratings and the Subprime Mortgage Meltdown TEACHING NOTE FOR: MOODY’S CREDIT RATINGS AND THE SUBPRIME MORTGAGE MELTDOWN This case illustrates the following themes and concepts discussed in the chapters listed: Theme/Concept Chapter Stakeholder analysis Ethics and ethical reasoning Organizational ethics and the law Public policy Government regulation of business Shareholder rights Executive compensation 1 4 5 8 8 14 14 Case Synopsis: In the mid-2000s, Moody’s, the leading credit rating agency in the world, evaluated thousands of bonds backed by “subprime” residential mortgages—home loans made to people with low incomes and poor credit. When housing prices began to decline in 2006, the value of many of these bonds collapsed, and Moody’s was forced to downgrade them steeply. In late 2008, several investment banks, commercial banks, and mortgage lenders that had been heavily involved in the subprime market failed. In the wake of these failures, credit froze up, consumer confident plunged, and job losses deepened across the global economy. Although the financial crisis had many causes, some analysts believed that Moody’s and other credit rating agencies had played a key role by underestimating the risks inherent in mortgage-backed securities. The case draws on publicly available data, including internal documents released by Moody’s in connection with a Congressional hearing in October 2008, to explore the multiple causes of the financial crisis and Moody’s role in it. It challenges students to consider how businesses, governments, and society can better assure the integrity of the credit rating industry. Case 1-1 Case 1: Moody’s Credit Ratings and the Subprime Mortgage Meltdown TEACHING TIP: VIDEOS AND PODCASTS Several videos and podcasts are available that may be used with this case. They include the following: On August 30, 2007, the NewsHour with Jim Lehrer (the PBS news program) ran a report by economics correspondent Paul Solman, entitled “Risky Subprime Market Sends Ripples through Financial World.” In the segment, Solman interviews an economics professor, who explains subprime mortgages and securities backed by them. The segment is available as streaming video from PBS at: http://www.pbs.org/newshour/bb/business/july-dec07/subprime_08-30.html On March 21, 2008, the NewsHour with Jim Lehrer ran another report by Solman, entitled “Examining the Roots of U.S. Economic Woes.” Solman uses some clever dime-store props and interviews with several experts to explain how $200 billion or so in bad housing debt precipitated a worldwide financial crisis. The segment is available as streaming video from PBS at: http://www.pbs.org/newshour/bb/business/jan-june08/domino_03-21.html The instructor may wish to show some or all of these two PBS segments in class. On December 14, 2008, CBS’s Sixty Minutes ran a story titled “A Second Mortgage Disaster on the Horizon?” The segment predicted a second wave of mortgage defaults (and collapse of bonds backed by them) over the following few years, as so-called Alt-A and payment-option ARM loans reset. This segment may be useful as an epilogue to the case. The transcript and streaming video are available at: http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2008/12/12/60minutes/main4666112.shtml In April 2008, Public Radio International’s radio show “This American Life” aired an episode entitled “The Giant Pool of Money.” This show later won a DuPont-Columbia award for journalistic excellence. In making the award, the judges wrote: “Through terrific storytelling and economic insight, the reporters demystify the subprime mortgage meltdown using personal stories to explain such terms as derivatives, tranches, short selling and credit swaps.” The episode is quoted in the case. The instructor may wish to require that students listen to the complete podcast before class (it runs approximately one hour). It is available at: http://www.thislife.org/radio_episode.aspx?episode=355. For students who wish to read rather than listen, a transcript is available at: www.thislife.org/extras/radio/355_transcript.pdf. Case 1-2 Case 1: Moody’s Credit Ratings and the Subprime Mortgage Meltdown Discussion Questions: 1. What did Moody’s do wrong, if anything? 2. Which stakeholders were helped, and which were hurt, by Moody’s actions? 3. Did Moody’s have a conflict of interest? If so, what was the conflict, and who or what were the principal and the agent? What steps could be taken to eliminate or reduce this conflict? 4. What share of the responsibility did Moody’s and its executives bear for the financial crisis, compared with that of home buyers, mortgage lenders, investment bankers, government regulators, policymakers, and investors? 5. What steps can be taken to prevent a recurrence of something like the subprime mortgage meltdown? In your answer, please address the role of management policies and practices, government regulation, public policy, and the structure of the credit ratings industry. Discussion Questions and Answers: 1. What did Moody’s do wrong, if anything? Moody’s misjudged the risk inherent in thousands of complex asset-backed securities, particularly residential mortgage-backed securities that it rated during the mid-2000s. It stopped rating RMBSs in mid-2007, and over the following year downgraded more than 5,000 of them, including 90 percent of those first rated in 2006 and 2007. The downgrades represented an acknowledgment by Moody’s that its original ratings were inaccurate. Arguably, Moody’s failed to consider the risk inherent in the loans underlying these complex asset-based securities, putting investors and, indeed, the entire financial system at risk. In its own defense, Moody’s would likely point out that ratings are simply an opinion of the statistical probability of default. It would no doubt argue that when the ratings were first issued, they were based on the best information and statistical models available and therefore provided an accurate probability estimate at that time. 2. Which stakeholders were helped, and which were hurt, by Moody’s actions? Stakeholders are those people and groups that affect, or are affected by, an organization’s decisions, policies, and operations. Many stakeholders, both market and nonmarket, were affected by Moody’s inaccurate ratings. Initially, many stakeholders benefited from Moody’s high ratings of RMBSs. Moody’s shareholders benefited greatly from the company’s stellar financial results during the early 2000s; as shown in Exhibit B, share value rose 354 percent over a 5-year period, well above the S&P 500 composite index and its comparison group. Case 1-3 Case 1: Moody’s Credit Ratings and the Subprime Mortgage Meltdown Institutions, governments, and individuals who invested in RMBSs benefited, since these securities typically paid interest rates above those paid by other investments with comparable investment grade ratings during 2004-2007. Mortgage originators and investment banking firms earned high fees from selling, packaging, and marketing mortgage loans during the housing bubble of 2003-26— transactions that were enabled and facilitated by investment-grade ratings on mortgagebacked securities. However, investors were later badly hurt when mortgage-backed securities dropped precipitously in value, sometimes becoming entirely worthless. Even investors who did not hold RMBSs directly were hurt, as the stock and bond markets fell broadly in response to the financial crisis. The case reports that in 2008, investors lost around $7 trillion in the market value of their assets. However, all of these groups, and others, suffered tremendous losses when these RMBSs later collapsed in value. Investment banks, mortgage companies, and commercial banks collapsed. Moody’s own stock fell in value. Stock and bond investors lost trillions of dollars in assets. And, taxpayers were forced to assume much of the enormous cost of bailing out many of the investment banks and commercial banks that failed and homeowners that lost their homes. TEACHING TIP: “A” STUDENT / “C” STUDENT Excellent students will recognize that many of the parties that benefited in the short run from Moody’s ratings—including home buyers, mortgage originators, investment banks, and investors—took huge losses later when securities backed by bad loans collapsed and were downgraded. Case 1-4 Case 1: Moody’s Credit Ratings and the Subprime Mortgage Meltdown 3. Did Moody’s have a conflict of interest? If so, what was the conflict, and who or what was the principal and the agent? What steps could be taken to eliminate or reduce this conflict? THEORETICAL LINK: CONFLICT OF INTEREST The term conflict of interest has been defined by the Encyclopedic Dictionary of Business Ethics as follows: [A] conflict of interest occurs if and only if a person P is in a relationship with one or more others requiring P to exercise judgment in their behalf, and P has a (special) interest tending to interfere with the proper exercise of judgment in that relationship.1 Another definition has been offered by John Boatright: [A] conflict of interest is a conflict that occurs when a personal interest interferes with a person’s acting so as to promote the interest of another, when the person has an obligation to act in that other person’s interest.2 In ethics theory, the person or organization exercising judgment is normally referred to as the agent, and the person or organization on whose behalf judgment is exercised is referred to as the principal. Conflicts of interest are normally considered unethical for several reasons. Persons and organizations that have contracted with an agent for a service that requires an exercise of judgment have a reasonable expectation that the agent will act in the principal’s interest, not the agent’s. Failure to disclose a conflict of interest represents deception and may result in injury to the principal. Many ethicists believe that even the appearance of a conflict of interest should be avoided, because it undermines trust in the relationship. Did Moody’s have a conflict of interest? Yes. As the case explains, Moody’s was paid by the same institutions that issued the bonds it rated. If so, what is the conflict, and who or what is the principal and the agent? Moody’s core business was rating the safety and security of bonds issued by companies, governments, and public agencies, as well as of securities comprised of pools of debt. The U.S. government had granted Moody’s a quasi-regulatory role in the bond market. Investors relied on credit ratings to assess the relative risk of various fixed-income securities. In this instance, Moody’s was the agent that exercised professional judgment on behalf of investors, the principals. Yet, since the 1970s, Moody’s had charged issuers to rate their bonds. In order to bring in business and build market share, Moody’s and other rating agencies had an interest in Michael Davis, “Conflict of Interest,” pp. 131-133 in Patricia H. Werhane and R. Edward Freeman, eds., Encyclopedic Dictionary of Business Ethics (Oxford, UK: Blackwell, 1997). 2 John R. Boatright, Ethics and the Conduct of Business, 4th ed. (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2003), p. 140. 1 Case 1-5 Case 1: Moody’s Credit Ratings and the Subprime Mortgage Meltdown serving the issuers. Arguably, Moody’s main goal was to satisfy the bond issuer—who naturally would seek the highest possible rating. This could well conflict with the interest of the investor, who naturally would seek an accurate rating. What steps could be taken to eliminate or reduce this conflict? Moody’s could take a number of steps to eliminate or reduce this conflict. The company could eliminate the conflict by drawing revenue from a source other than fees charged to issuers. This would require a complete change in its business model. Possible options might include: Charge pensions, mutual funds, and other institutional investors to subscribe to a rating service to help them evaluate the safety of fixed-income securities. (In effect, this would mean a return to the business model Moody’s had used prior to the 1970s.) Require the government to fund the bond-ratings services provided by the credit-rating agencies, as an extension of its regulatory obligation to protect the interests of investors in publicly-regulated markets. Pay rating agencies according to a standard formula from a fund that is paid into by institutions each time they issue a bond, thus separating the fee paid from any specific bond or transaction. TEACHING TIP: COUNTER ARGUMENTS After each of these options is proposed, ask students to critique them. For example, in the case, Moody’s CEO Raymond McDaniel makes several arguments against the investor-pays business model, suggesting that it carries its own conflicts of interest. As an alternative, the company could attempt to manage the conflict. As explained in the case, steps the company had already taken included: Rate bonds by a committee, not by an individual. Bar analysts from owning stock in institutions whose bonds they rated. Separate compensation from revenue based on analyst’s own ratings. Students may suggest other methods of managing the conflict, such as: Compartmentalize conflicting roles within the agency, e.g., separate the marketing and business development function from the ratings function. Bar the provision of research or other services to institutions whose bonds the agency rates. Base compensation of analysts (and the executives who manage them) on the long-term accuracy of the ratings (or, penalize originators of ratings that later prove inaccurate). Case 1-6 Case 1: Moody’s Credit Ratings and the Subprime Mortgage Meltdown TEACHING TIP: “A” STUDENT / “C” STUDENT Excellent students will recognize that the procedures Moody’s has adopted to manage conflicts of interest address possible individual conflicts (e.g., an individual analyst owns stock in a company whose bonds he rates), as opposed to organizational conflicts (e.g., Moody’s is paid by the institutions whose bonds it rates). 4. What share of the responsibility does Moody’s and its executives bear for the financial crisis, compared with that of home buyers, mortgage lenders, investment bankers, government regulators, policymakers, and investors? One way to approach this question is to ask students to make the case for the responsibility of each of these parties for the financial crisis. All of these parties acted irresponsibly, and thus shared part of the blame for the financial crisis. Home buyers: Many people irresponsibly purchased homes that they could not afford, based on lax lending standards, low initial monthly payments, and an inaccurate assumption that housing values would continue to rise indefinitely. In many cases, it was in their short-term interest to do so, because these purchases enabled them to improve the quality of their housing. Mortgage lenders: Many lenders made loans to borrowers of dubious creditworthiness, generating large fees. So long as they were able to quickly package and sell these loans, they did so with little or no risk. Investment bankers: Large Wall Street investment banks repackaged risky home loans into complex asset-backed securities and sold them to investors, generating large underwriting fees. So long as they were able to move them quickly off their books, they did so with little risk. Government regulators: Regulators contributed to the financial crisis by failing to rein in risky lending and monitor the market in asset-backed securities, and by pre-empting state regulatory efforts to curb predatory lending. Government policymakers contributed by promoting low interest rates and other policies to encourage home ownership for low-income individuals. Moody’s and its executives (and, by extension, other leading credit rating agencies) contributed by providing investment-grade credit ratings to many mortgage-backed securities, enabling them to be widely marketed to investors. Investors: Investors, particularly institutional investors, purchased risky assets in search of higher returns. In short, all parties bore a share of the responsibility; each was pursuing its own self interest in an inadequately regulated system. Each party sought to benefit, while passing the risks along to others. Case 1-7 Case 1: Moody’s Credit Ratings and the Subprime Mortgage Meltdown TEACHING TIP: WHO BORE THE GREATEST RESPONSIBILITY? Students may be asked to debate which party was most responsible. Some will argue that the credit rating agencies bore the greatest responsibility, because the RMBSs could not have been sold without investment-grade ratings. Other will argue that the home buyer was ultimately responsible, because without bad loans the subprime market would not have collapsed. THEORETICAL LINK: MORAL HAZARD One concept that the instructor may find useful is “moral hazard.” The term “moral hazard” refers to the likelihood that someone who is protected from risk will behave differently from one who is exposed to risk. The term first arose in the insurance industry, where an insured person might be expected to take greater risks than an uninsured person. For example, someone with auto theft insurance might be less careful to always lock his or her car, or a person covered by flood insurance might be more likely to buy a house in a flood plain. Holden Lewis, writing for bankrate.com, offered a clear explanation of the relevance of this concept to the subprime mortgage meltdown: “…each link in the mortgage chain collected profits while believing it was passing on risk to the next link in the chain. Brokers weren't lending their own money, so they were pushing risks onto the lenders. Lenders sold mortgages soon after underwriting them, pushing the risk onto investors. Investment banks bought the mortgages and chopped up mortgage-backed securities into slices, with some slices being less risky and other slices being more risky. Investors bought securities and hedged against the risk of default and prepayment, pushing those risks further along. All of these businesses accepted profits and tried to leave the next guy vulnerable to risk. Participants thought they were insulated from the negative consequences of bad decisions.”3 Lewis did not mention credit rating agencies in his account, but arguably they also passed along risk, giving subprime mortgage-backed securities investment grade ratings, with the assumption that they would not bear any costs of possible later downgrades. In short, every actor in a complex system acted recklessly, believing that they were insulated from negative consequences of their actions. 5. What steps can be taken to prevent a recurrence of something like the subprime mortgage meltdown? In your answer, please address the role of management policies and practices, government regulation, public policy, and the structure of the credit ratings industry. Students may make a number of recommendations, including the following: 3 Holden Lewis, “Moral Hazard Helps Shape Mortgage Mess,” www.bankrate.com, April 18, 2007. Case 1-8 Case 1: Moody’s Credit Ratings and the Subprime Mortgage Meltdown Change the business model of the credit rating industry so that revenue flows not from issuer fees but from a government funds, a “blind” trust, or investor subscriptions (see above.) Change credit rating firm executive compensation and employee incentives so that managers and analysts are rewarded based on performance of their ratings, with a portion of compensation deferred and dependent on the long-term performance of ratings. Implement government regulations that set higher minimum underwriting standards for personal and commercial loans. Enforce standards of personal responsibility and accountability by restricting the use of no down-payment and no-recourse loans. Implement government policies that require mortgage lenders, investment banks, and commercial banks to assume a greater share of the risk of loans that they make or package and sell to others. In other words, prohibit the complete “hand off” of risk. Permit greater competition in the credit rating industry by making it easier for new entrants to qualify as NRSROs. Give the SEC or other government agency greater resources and authority to regulate highly complex asset-backed securities. Temporarily withdraw the NRSRO designation from credit rating agencies with poor results. TEACHING TIP: OTHER PERSPECTIVES The instructor may wish to ask students to investigate what others have said on this issue. Some sample ideas follow. Robert Reich, former Secretary of Labor in the Clinton administration, wrote in his blog on October 23, 2007: It’s obvious why credit-rating agencies didn't blow the whistle [on the risk inherent in RMBSs]. (They didn't blow the whistle on Enron or WorldCom before those entities collapsed, either.) You see, credit-rating agencies are paid by the same institutions that package and sell the securities the agencies are rating. If an investment bank doesn’t like the rating, it doesn’t have to pay for it. And even if it likes the rating, it pays only after the security is sold. Get it? It’s as if movie studios hired film critics to review their movies, and paid them only if the reviews were positive enough to get lots of people to see a movie… The whole thing rested on a conflict of interest analogous to that of stock analysts who, before the dotcom bubble burst, advised clients to buy stocks their own investment banks were issuing. The remedy for that was to split the two functions – analysis from investment banking. Case 1-9 Case 1: Moody’s Credit Ratings and the Subprime Mortgage Meltdown The remedy here is to do much the same: bar issuers from paying credit-rating agencies for rating their securities. If investors want to examine securities’ ratings, they or the pension or mutual funds they invest through can subscribe to the service – just as moviegoers subscribe to publications where reviews appear.4 Representative Jackie Speier (Democrat-California), a member of the House Oversight and Government Reform Committee, published a newspaper op-ed after the hearing recommending changes in the rules governing the credit rating agencies. She wrote: Here are four ideas: 1) Pay rating agencies from a fund that is paid into by bond sellers, similar to the method the Food and Drug Administration uses to fund drug research. This arm's-length transaction would return the rating agencies to answering to investors. 2) Prohibit rating agencies from providing consulting services to the institutions they rate. 3) Create a Consumer Financial Products Safety Commission. Like the Consumer Products Safety Commission is empowered to stop dangerous toys and other products from being sold, a financial productions commission would have the authority to prevent overly risky financial instruments from reaching market. 4) Provide better transparency of mortgage-backed securities by allowing easier access to information documenting their likelihood of default.5 Epilogue: As of the time of writing, the financial crisis was ongoing, and Moody’s role in it continued to be debated. As an assignment, students may be asked to research events subsequent to the hearings in October, 2008. In particular, they may be asked to investigate the status of: 4 5 lawsuits brought by union pension funds that lost money in Moody’s-rated securities; lawsuits brought by Moody’s own shareholders who charged that Moody’s had used inflated ratings to keep its own revenues and share value high; Moody’s own internal review of its ethics procedures; the SEC’s proposed rules governing the big three credit rating agencies; negotiations with various state attorneys general over fees charged for reviewing mortgage-backed securities. http://robertreich.blogspot.com/2007/10/they-mystery-of-why-credit-rating.html. Jackie Speier, “Credit Rating Agencies Are No Longer First Rate,” San Francisco Chronicle, December 17, 2008. Case 1-10