Everyday Rituals

advertisement

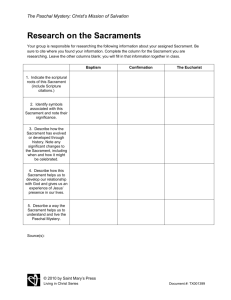

Everyday Rituals Each day of our lives there are things we do at the same time, in the same place and in the same order. These routine actions become rituals when we intentionally give them a higher meaning and purpose. Rituals help us understand ways of being and ways of doing in a particular culture and context. In the classroom context, routines and rituals may involve unpacking our bags, putting books away and gathering for morning prayer, collaborating in learning tasks and positive participation in playground games and activities. Rituals help us to join in and give us a sense of identity and belonging. They help us enjoy special times and activities and they remind us of people and times that are important. Religious rituals focus on the mystery of the relationships between God, humankind and all of creation. Ritualistic actions, prayers and symbols are used repetitively and respectfully to create an atmosphere of devotion and connectedness with God. Rites of the Sacraments of Initiation To become a new member of an organisation or community is a significant event for both the individual and the group. For the individual, it is a beginning that offers new possibilities for life. For the group, it provides the prospect of growth and preservation. It is usual for there to be conditions of entry and procedures of admission. These both ritualise admittance and protect the integrity and purpose of the group. The Church similarly has its rites of initiation. Baptism, Confirmation and the first reception of Eucharist combine to form the sacraments of Christian Initiation. Through them one enters fully into the life of the Church. They are celebrated together for adults as the completion of the catechumenate – the lengthy process of preparation for Church membership. In the Eastern Church, they are also celebrated together in the case of infants. In the Western Church, it is customary to baptise infants, but Confirmation and Eucharist are delayed until later. It is becoming more common for the traditional order of the sacraments to be restored, with Confirmation preceding first Eucharist. Today it is also more common to test the intentions of those seeking Baptism for their children and to offer instruction to them by way of preparation. Thus children vicariously through their parents experience those other elements of initiation that are incorporated into the adult initiation process. Baptism is a serious step—a step for which believers spend much time getting ready. Special clothes, a candle to light the way, water for growth, oil for strength, even companions for the journey are associated with Baptism. This is the beginning of a much longer journey of commitment and discipleship. The journey begins with an invitation, a call from God through the Christian community to live the gospel as committed disciples of Christ. Acceptance of the invitation follows and believers’ responses are ritualised and made visual and "real" in the celebration of Baptism. Adult Baptism was the norm in the Church of the first three centuries. Those who were interested in Christianity were invited to join the Christian community on a journey of faith. Those who accepted the invitation became candidates for the sacraments of initiation (Baptism, Confirmation and Eucharist). The candidates were called catechumens and entered into a step-by-step process toward full membership in the Church. This process was called the Catechumenate. Joining the Church in the early centuries was no easy matter. The Baptismal commitment was not to be taken lightly. The entire Church would pray for, and with the catechumens, instructing them in gospel values, sharing the faith life of the Church and celebrating the stages of the faith journey with special rituals of welcoming and belonging. The final Lent before the initiation was a special time for catechumens. It was like a 40-day retreat including prayer, fasting and other forms of self-scrutiny as they prepared to accept the faith and be received in the Church. Lent started out as the Church's official preparation for Baptism, which was celebrated only once a year at the Easter Vigil. By the beginning of the fifth century, the catechumenate process itself had virtually disappeared. The sacraments of initiation became three separate sacraments celebrated at separate times. Soon adult Baptisms declined and infant Baptism became the norm. Source: The Sacrament of Baptism: Celebrating the Embrace of God by Sandra DeGidio, O.S.M. Since Vatican II the Church has re-established the Adult Catechumenate (or Rite of Christian Initiation of Adults) as the norm for its receiving of new adult members. Importance is attached to instruction in the proper behaviour of an adult. There is lengthy instruction in the Christian faith by catechists. As time draws near for initiation, the candidates are publicly tested in ceremonies known as the Scrutinies. And finally they are admitted to full membership of the Church through the sacraments of Baptism, Confirmation and Eucharist. They are sealed with chrism and clothed in the white robe of a purified neophyte. Baptism as welcoming Each sacrament is an action of the Church which is the Body of Christ. It is therefore a ritual through which God is present, touching the life of both the recipient and the faith community in some particular way. Baptism is a rich reality in which one is immersed (baptisein in Greek) into the life of the Risen Christ. This involves a death to sin and a rising to a new life as son or daughter of God. Confirmation as sealing Jesus is known as the Christ – the anointed one (from the Greek kristos). He began his public ministry (in Luke's gospel) by reading from the text of Isaiah: ‘The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, he has anointed me…’ At his baptism in the Jordan, the Spirit came upon Jesus and his mission was sealed by the Father's word: ‘You are my Son, the beloved; with you I am well pleased.’ After his resurrection Jesus communicated this same Spirit to his followers. As the Body of Christ, the Church is the Spirit-filled messianic people. Confirmation (or Chrismation in the Eastern Church) is the sacrament through which the baptised are sealed with the gift of the Holy Spirit. The symbol of anointing with oil (chrism) is used. This points to one's consecration as a Christian: sharing more completely in the mission of Jesus and in the fullness of the Holy Spirit with which he is filled. A seal is a sign of authority, of personal ownership. So slaves and soldiers bore the seal of their master. Confirmation imparts a spiritual seal or character, which marks the Christian as belonging wholly to Christ. It calls one to share in Christ's priestly, prophetic and kingly mission. Eucharist as Table Companionship No sacrament is richer in meaning and symbolism than the Eucharist. Vatican II described it as ‘the source and summit of the Christian life’. Four symbols of Eucharist include; bread and wine, the Word, the presiders and the community gathered. By invocation of the Holy Spirit, Jesus who is the Bread of Life, is made present sacramentally. Christians are fed at this table of the Lord. The first fruit of their sacramental nourishment is a closer union with Christ. ‘Those who eat my flesh and drink my blood abide in me and I in them.’ (John 6:56) Consequently, through Communion, one is bound more closely in love to all who form the Body of Christ. One is fortified against sin and strengthened to meet the challenges of the Christian life. The word of God that is proclaimed and broken open during the Mass. ‘The Eucharistic table set for us is the table both of the Word of God and of the Body of the Lord.’ (Vatican II) When the Scriptures are proclaimed in the community, Christ is present as God's Word, nourishing our minds and understanding and deepening our faith. Rituals of the Sacraments of Healing Sacraments of Healing Penance and the Anointing of the Sick are known as Sacraments of Healing. The foundation of these two sacraments of healing is to be found in the life and ministry of Jesus. The Catechism of the Catholic Church in its introduction to the section on the Sacraments of Healing states: “ The Lord Jesus Christ, physician of our souls and bodies, who forgave the sins of the paralytic and restored him to bodily health (cf. Mk 2:1-12), has willed that his Church continue, in the power of the Holy Spirit, his work of healing and salvation, even among her own members. This is the purpose of the two sacraments of healing: the sacrament of Penance and the sacrament of Anointing if the Sick. Healing Humans have always found something lacking in their personal behaviour. Moral conduct has always been guided by codes, taboos, and laws within families, clans or tribes. Some process of making amends has always been part of human experience, too. Jesus himself and the earliest of Christians were used to penitential rituals prescribed by the Hebrew Scriptures and Jewish traditions. The earliest Christian communities continued their Jewish penitential practices. They confessed to one another and prayed for healing (James 5:16). When Christ’s second coming did not happen as quickly as they once thought, and church communities had to deal with members who had not lived up to their commitment, there evolved a need for some kind of absolution ritual. At a very early date, a penitential formula was included when Christians gathered for the Eucharist. By the 4th century a public ritual had evolved to deal with the most serious of sinners. This included a confession of sins to the local bishop and readmittance to the worshipping community after proof of conversion and extensive penance. The priestly authority to represent the church in absolving from sins was reserved first to the bishop and later to all priests. Sinners were publicly identified as penitents, a distinct group in the local parish. Centuries later, remnants of this public ritual identification would be preserved in our Ash Wednesday service. These penitents were often dismissed from the assembly after the Liturgy of the Word. Penances were harsh and often public, sometimes lasting for years or even a lifetime. Some common penances were: total abstinence from wine, meat, sexual relations with spouse, bathing, shaving or having ones hair cut. It was common to wear sackcloth, ashes, and even chains. At Mass these penitents were prayed over by the presider and congregation. Absolution and readmittance to the community occurred before the Easter Vigil, often on Holy Thursday. A common conviction was that there was only one opportunity for repentance after baptism. It was not unusual, therefore, for serious sinners to postpone entering the ranks of penitents until old age. A private form of confession and repentance, repeated frequently, evolved in monasteries because of the conviction that all are sinners to some degree. For the sake of uniformity, priest monks used small books listing common sins according to degree of seriousness and recommended penances for each. Effort was made to ensure that the punishment (penance) fir the crime (sin). By the 8 th century people were urged to confess at least three times each year, with confessing once a year, joined to the Easter duty of receiving communion, being mandated in 1215. Initially absolution was given when the penance was completed, by the end of the 10th century, absolution was given before the penance was completed and in the 11th century the use of penance books were discontinued. By the 13 th century this unofficial private form of the sacrament of penance had become the official sacrament, and a change in attitude had also evolved, with the forgiveness of sins occurring through the absolution by a priest rather than through the sorrow and penance of the penitents. A distinction between mortal and venial sins also occurred. Originally, mortal sins referred to the kind requiring public penance, now they described the kind that, unforgiven, would merit eternal punishment, whereas venial sins could easily be pardoned on both sides of death. By the middle of the 20th century shifts in moral thinking had occurred. Sin in the truest sense came to be associated more with internal choices about fundamental options rather than external actions and the gospel message rather than traditional moral laws once again became the effective guideline for morality. In 1973 the church responded to new insights and emphases and issued a new ritual containing three rites highlighting the communal dimension and call to conversion. The first rite is a private form that encourages priest and penitent to converse face to face, sharing prayer and Scripture together and including spiritual counselling and meaningful penance. A second rite is a semi-private form. It begins with an assembly devoted to song, prayer, Scripture reading, and preaching. Then penitents are invited to approach one of the priest confessors for a brief private confession and absolution. A third rite, a public form, is available in situations of emergency or when too many penitents are present for private confession. Sins absolved in this latter way are still to be confessed privately later. Sacrament of Penance True peace can be experienced in life only when we have received forgiveness for our faults and been reconciled with those we have offended. Jesus knew this well. The gospels show that bringing forgiveness into people’s lives was a major purpose of his ministry. When people sought healing, he first forgave their sins. Only then could they be truly healed in their whole person. Bodily cures alone could not bring lasting peace. Through the sacrament of Penance the Church continues Jesus’ ministry of forgiveness. The Catechism outlines four elements that combine to constitute the sacrament. On the part of the penitent these are: Contrition. Aware of one’s sinfulness, one approaches God’s mercy in a spirit of sorrow for sin. Confession. One makes an honest admission of one’s sins. The discipline of the Church requires that all mortal sins be confessed explicitly. Satisfaction. Sin both injures others and weakens ourselves. One must make amends for this through repairing harm done or through suitable penance. Absolution. We are reminded that Christ died and rose that we might be reconciled with God and obtain forgiveness of all our sins. That forgiveness is assured us: ‘I absolve you from your sins.’ The celebration of the sacrament has been revised in recent times to better reflect the positive nature of the encounter with Christ. The ritual begins with prayer, followed by a reading from Scripture. There is an examination of conscience and confession of sin in the light of God’s word. Absolution and imposition of penance follows and the rite concludes with praise of God’s goodness. There are rites of reconciliation to meet diverse circumstances. The first rite involves individual celebration and allows for fruitful dialogue between penitent and priest. It may be celebrated face to face or anonymously as desired. The second rite is a communal celebration, which better expresses the social dimension of sin and reconciliation. After prayers, readings, homily and guided examination of conscience, a brief individual meeting with the celebrant for confession and absolution follows. These are described as Rites of Reconciliation to celebrate the sacrament. They emphasise the dynamic nature of the sacramental encounter. God invites the penitent to repentance through the grace of conversion. God earnestly desires the salvation of every person. The penitent responds to the call to conversion and seeks reunion with God and all those harmed by one’s sins. The result is indeed a joyful reconciliation that puts behind the failures of the past and looks forward in confidence to a future to be lived in fidelity and harmony. The Sacrament of the Anointing of the Sick By the sacred anointing of the sick and the prayer of the priests, the whole Church commends those who are ill to the suffering and glorified Lord, that he may raise them up and save them. And indeed the Church exhorts them to contribute to the good of the People of God by freely uniting themselves to the passion and death of Christ (Lumen Gentium 11). Illness and suffering are part of human life. The sacrament of the Anointing of the Sick has as its purpose the giving of a special grace to support a person experiencing the difficulties of grave illness or old age. A foundational Scriptural text in relation to the sacrament is from the Letter of James. “Is anyone among you sick? Let them call for the presbyters of the Church, and let them pray over them, anointing them with oil in the name of the Lord; and the prayer of faith will save the sick person and the Lord will raise them up; and if they have committed sins, they will be forgiven.”(James 5: 14-15) The Anointing of the Sick is not a sacrament for those only who are at the point of death, though it is certainly for people who are dying. All members of the faithful who are gravely ill, whether death is imminent or not, can receive the sacrament. If a sick person who received the sacrament recovers health, he or she may receive this sacrament again in the case of another grave illness. If during the same illness the person’s condition becomes more serious, the sacrament may be repeated. The Sacrament of the Anointing of the Sick is a liturgical and communal celebration. The sacrament may be celebrated in the family home, in a hospital or church, for a single sick person of for a whole group of sick people. The sacrament may be celebrated within the Eucharist. If circumstances suggest, the sacrament can be preceded by the sacrament of Penance and followed by the Eucharist. The Liturgy of the Word, preceded by an act of repentance, opens the celebration of this sacrament. The celebration includes the following major elements: The priest in silence lays hands on the person who is sick and prays over them in the faith of the Church. The priest then anoints the sick person with oil, blessed, if possible, by the bishop. In addition to the Anointing of the Sick, the Church offers those about to die the Eucharist as viaticum. Viaticum is communion received at the moment of “passing over” to God and has a particular significance and importance in the light of Jesus’ words “He who eats my flesh and drinks my blood has eternal life, and I will raise hi up on the last day.” (Jn 6:54) Rituals of the Sacraments of Vocation Vocation One important tenet of a religious view of life is that there is purpose to the universe. God has created everything and especially human beings, for a purpose. The Creator directs life therefore towards discovering and responding to this calling or ‘vocation’. For the Christian the ultimate vocation is union with God. This is achieved throughout life by responding to particular calls that arise from one's unique circumstances. The Christian concept of vocation reflects belief in each human being having a personal relationship with God. As a created person an individual’s personal gifts and situation in life suggest ways in which life can believed in ways that are purposeful and fulfilling. Theologians speak of a ‘state of grace’ that God gives to enable each person to respond fruitfully to this calling. Vocation is therefore a religious concept. A person must discern and freely respond to God's call. It necessarily takes time and sometimes much trial before one discovers one's vocation. There are often practical barriers and disincentives to overcome. The support of family and of personal prayer is important. Sacraments of Commitment / Service Married life is a vocation to which most people are called. Through their union in love, the partners assist each other to live out their discipleship. They may also share in God's creative work by handing on life. For Christians who embrace marriage according to God's purpose, their union becomes a sacrament. It is a sign of the fruitful union between God and his people that is life-giving and that models community. The sacrament of matrimony offers the couple the graces they need to live out their commitment to each other and to raise a family. For this reason, sacramental marriage is an indissoluble and lifelong union. Within the life of the Church, some are called to serve in particular roles of leadership. The sacrament of Holy Orders consecrates bishops, priests and deacons to serve the people of God. The bishop is entrusted with a threefold ministry of teaching, sanctifying and governing a local church in communion with the church universal. The priest is a co-worker with the bishop, and usually serves a community known as a parish. The deacon, who has a more limited liturgical role, assists in the practical works of charity the local church undertakes. All baptised persons share in the priesthood of Jesus. In daily life they seek to bring about God's reign and to be instruments of grace to all they meet. Those called to Orders share in a special way in Jesus' priesthood. In the Latin (Roman) tradition of the Church, only males who undertake a celibate lifestyle are ordained. Since Vatican II one the three ordained orders, the diaconate has been made available to married males. Soon after Vatican II many dioceses in the United States ordained married deacons. In more recent times in Australia male, married deacons have been ordained as permanent deacons in some dioceses in Australia. Some of the roles of deacons include; preaching, baptising and presiding at funerals. Sacrament of Marriage Marriage is a basic way of giving and growing in love and together attaining salvation. We are not meant to live in isolation, but to find and fulfil ourselves through the love of others. (Gen 2:18 and 21-25). The marriage covenant, through which a man and a woman form with each other an intimate communion of life and love, is ordered to the good of the couple as well as to the generation and education of children. The Church regards the sacrament of matrimony as signifying the union of Christ and the Church. The sacrament gives spouses the grace to love each other with the love which Christ has loved the Church. The sacrament of matrimony perfects the human love of spouses, strengthens their indissoluble unity and sanctifies them on the way to eternal life. Marriage is based on the free consent of the man and the woman celebrating the sacrament. The parties entering into the covenant of matrimony must want to give themselves each to the other, mutually and definitively, in order to live a covenant of faithful and fruitful love. The sacrament of Matrimony establishes the couple in a public state of life in the Church. Because of its public and ecclesial nature, it is fitting that the celebration of the sacrament be public and within the framework of a liturgical celebration, before a priest (or a witness authorised by the Church), the witnesses and the assembly of the faithful. Unity, indissolubility and openness to fertility are essential to marriage. By its very nature marriage and married love is ordered to the procreation and education of the offspring. Spouses to whom God has not granted children can nevertheless have a married life full of meaning, in both human and Christian terms. The marriage of such couples can manifest fruitfulness of hospitality and of sacrifice. The Catechism of the Catholic Church recognises the pastoral reality that in spite of the high ideals of the sacrament some marriages break down and spouses separate and obtain a civil divorce. The Church shows pastoral concern and care for those whose marriages have broken down. Although spouses may be separated from each other, they are not separated from the Church because of the breakdown in their marriage. The Catholic Church does not recognise the possibility of a church sanctioned divorce for a sacramental marriage celebrated in the Catholic Church. In some cases, the Catholic Church may grant former spouses an annulment. Annulment is a declaration by Church authority that a given marriage did not fulfil the conditions and criteria of a truly sacramental marriage. An annulment or a “decree of nullity” as it is officially known, is a declaration by a competent authority of the Church that a marriage was invalid from the beginning. This can arise from a “diriment” or invalidating impediment: for example, a basic defect in consent to marriage, or a condition” placed by one or both parties on the nature of the marriage as understood by the Church. An annulment is not a divorce. Such a decision would be taken by the competent church authority on the recommendation of a competent church tribunal normally at the diocesan level. The Church may dissolve a valid marriage when one or (or both) of the parties is not baptised as a Christian. This was a practice of the early Church and is mentioned by St Paul in 1 Cor 7:12-15. It is known as the “Pauline Privilege”. It is preferred that Christians marry Christians rather than persons who do not share their faith, especially keeping in mind the advantage for children of the marriage. The marriage between a Catholic and a non-Catholic Christian is known as a “mixed marriage” in the Catholic Church. The Catholic party is bound to the normal form of marriage: this must take place in the presence of the local ordinary (bishop) or the pastor or priest (or deacon delegated by either of the parties) with two witnesses. Catholic marriages are normally celebrated at a nuptial Mass. In the case of a mixed marriage, a non-Catholic minister may also assist at the ceremony. Attendants at mixed marriages may also be non -Catholic. Called from the Community Teacher Background Holy Orders is the sacrament of apostolic ministry. The sacrament of Holy Orders includes three degrees: episcopate, presbyterate and diaconate. The word order in the ancient Roman world designated an established civil body, especially a governing body. The Latin word ordinatio (ordination) meant being admitted to and incorporated into an ordo (order). The liturgy of ordination speaks of the ordo episcoporum (order of bishops), ordo presbyterorum (order of priests) and ordo diaconorum (order of deacons) Today the word “ordination” refers to the sacramental act that integrates a man into the order of bishops, presbyters (priests) or deacons. The essential rite of the sacrament of Holy Orders for all three degrees consists in: 1. the placing of the hands of the ordaining bishop on the head of the person to be ordained (the ordinand) and 2. the bishop’s specific consecratory prayer petitioning God for the outpouring of the Holy Spirit and the gifts of the Holy Spirit related to the ministry to which the candidate for ordination is being called and ordained. As in all sacraments, additional rites surround the celebration of the sacrament vary greatly among the different liturgical traditions. In the Roman Catholic Latin rite, the following elements make up the liturgy of ordination: Presentation and election of the ordinand Instruction by the bishop Examination of the candidate Litany of the saints The above elements attest that the choice of the candidate is made in keeping with the practice of the Church and prepare for the solemn act of ordination. There follows: an anointing with holy chrism of bishop and priest as a sign of the special anointing of the Holy Spirit who makes fruitful the priestly and episcopal ministry. giving of the book of the Gospels, the ring the mitre and the crozier to the bishop, as the sign of his apostolic mission to proclaim the Word of God, of his fidelity to the Church and his office as shepherd of the Lord’s flock. presentation to the priest of the paten and the chalice, a symbol of the offering of the Eucharistic sacrifice on behalf of the people of God. the giving of the book of the Gospels to the deacon who has just received the mission to proclaim the Gospel of Christ. The sacrament of Holy Orders and the liturgy of ordination are to be seen in the context of the whole Church as a priestly people. Through baptism, all the faithful share in the priesthood of Christ. Based on this “common priesthood of all the faithful” and ordered to its service, there is another participation in the mission of Christ. This is the ministry conferred by the sacrament of Holy Orders. The ministerial priesthood differs in its essence from the priesthood of all the faithful, since it confers a sacred power for the service of the faithful. This service is exercised through teaching, divine worship and pastoral governance. The bishop receives the fullness of the sacraments of Holy Orders that integrates him into the College of Bishops and makes him the head of the particular Church entrusted to him. As a successor of the apostles and a member of the Episcopal College, a bishop shares in the apostolic responsibility and mission of the whole Church under the authority of the Pope. Priests are united with the bishops in priestly dignity and are called to be the co-workers of the bishop. Priests form a grouping (presbyterium) around their bishop and share with the bishop responsibility for a particular Church community- usually a diocese. Priests receive from the bishop the charge of a particular parish community or other responsibility in the local Church. Deacons are ministers ordained for tasks of service in the Church. Deacons do not receive the ministerial priesthood, but ordination confers on them important functions in the ministry of the word, divine worship, pastoral governance and especially the service of charity.