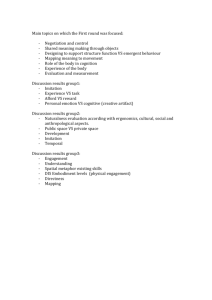

Some felt consequences of good and bad communication1

advertisement

Some felt consequences of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ communication “If it be now, ’t is not to come; if it be not to come, it will be now; if it be not now, yet it will come: the readiness is all” (Hamlet. Act v. Sc. 2). Communication as ‘transmission of information’: $ $ $ $ Currently, communication is thought of as the transmission of information: A tells B ‘something’, and B ‘gets it’. This is the case when everything works well. But there are a number of unexamined ‘background’ assumptions upon which its ‘working well’ depends (I will go into some of these in a moment). Indeed, the ‘information transmission’ transmission model of communication is not how our actual speech communication works at all – all our talk is understood for “another first time” (Garfinkel, 1967, p.9); if it wasn’t, if it was all a matter of talking according to already established rules, then no unique meanings would be possible. Communication and the ‘arousal of expectations’: $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ Before going further with the ‘transmission’ model of communication, I need to point out that human beings are living beings. All living things are responsive to events occurring in their surroundings – they cannot not be responsive. Thus we cannot not be responsive, bodily, to the others (and othenesses) around us. Our bodies spontaneously respond to events in our surroundings whether we like it or not. Indeed, we do not simply have living bodies; we are living bodies, and as a consequence, we have a bodily relation to our surroundings – we are (or can be) ‘in touch with them’, so to speak, in varying degrees. The degree of our ‘in touchness’ is known to us in terms of our feeling ‘at home’ or not within them. Perhaps the most well-known circumstance which brings this ‘home’ to us, i.e., which is familiar to us, is car driving – only after a fair degree of practice do we come to embody the required anticipations to drive safely in many variable situations. This raises the question: Can we learn similarly, in many others situations, to anticipate what we are about to encounter in our surroundings and be at the ready, so to speak, bodily, with the most appropriate kind of response? Yes we can – we often call such embodied readinesses, ‘habits’, ‘attitudes’, ‘inclinations’, ‘instincts’, and/or so on. I have used the term ‘readiness’ here as I want to suggest both that what is at issue is to do with our embodied expectations and anticipations in a particular situation, and also, that as such, these ‘instincts’ or ‘habits’, or whatever, are much more fluid and open to change than has been previously thought. These embodied readinessses are not open to our conscious deliberations – they have the character of the spontaneous readiness with which we approach another person with a smile, our hand outstretched, ready either to shake their hand or to hug and kiss. Failures to exhibit such expected readinesses can provoke a felt questioning: “Why so reluctant, why so unforthcoming, what’s wrong?” Difficulties of the mind and difficulties of the body: 1) solving problems, and 2) resolving on new lines of action: $ $ The comments above, if they have in any way been successful – as a communication, not of information, but as a set of events spontaneously evoking felt responses – have perhaps changed our orientation towards communication, i.e., changed the way we see it, changed our expectations and anticipations as to what we will ‘see’ as we look into it. With the ‘transmission model’ in mind, we look for and expect to find the ‘information’ transmitted. $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ With the fact in mind that we living embodied beings – who cannot not be responsive to events occurring in our surroundings – we can look for and expect to find living expressions of people’s felt responses to what is said to them. We ask someone a question and expect an answer to it (and both we and they know whether it is being answered or not); we issue a greeting (and in the vigour of the person’s response or lack of it we judge their mood today); we wish to explore an issue (instead of asking further open questions our respondent closes the issue with a ‘problem solved’ answer); and so on. In all the examples above, there are comparisons between two kinds of difficulties: (1) difficulties which can be seen as problems which can be solved by thinking of an appropriate framework, system, or theory of some kind, which enables one to say to those around one who are puzzled about something. Here, the criterion of success is their saying in reply: Oh, now I see it, now I get it – a trouble here is that this can be as far as it goes: the solution is at the level of talk, not practical action. (2) The other kind of difficulty is like the difficulty one experiences in coming to live in a new city: one does not know one’s way about – the difficulty is at best thought of in terms of our lack of an embodied readiness to act in certain ways, the lack of an embodied readiness, say, to recognize, i.e., notice, the signs relevant to the task in hand. Example: I have just moved to a new city (Norwich). I needed to find a special electronics shop, I go into an unsuitable one: “Can you tell me a shop where I can find an X?” “Oh yes, there’s one on St. Benedict’s street, and another on Anglia Square.” “Where’s Anglia Square?” “Oh, you know the Travel Inn?” “No!” “Well you know Duke Street?” “Yes.” “Well you cross over the road there.” “What road?” “The one at the bottom of Duke Street.” “Oh, OK, thanks, I’ll ask someone when at the bottom.” In a unique practical situation, getting ‘in touch’ with it, getting oriented, getting to ‘know one’s way around’ within it and where ‘to go next’, getting to know what kind of situation (context) it is and what it requires of you, is often one’s main bewilderment in a new circumstance. But sometimes, getting oriented can be a matter of ‘seeing’ the situation differently: as, for instance, in the circumstances here, where I have introduced the idea of communication being much more to do with arousing expectations, anticipations, changing orientations or relationships, than it being a matter of transmitting information. The importance of our being appropriately oriented cannot be emphasized enough. Lacking the ability to ready ourselves appropriately, i.e., to orient, to the unique nature of our current circumstances (in a conversation, say), we would not only not know ‘where’ at any one moment we are, we would also not know ‘where to go next’. Without the appropriate responses ‘at the ready’, so to speak, as scientists and academics we would not know how to test our theories empirically, nor would we be able to judge whether ‘evidence’ was in fact evidence, or whether ‘a proof’ was in fact a proof. The issue is the same for any practitioner also: What kind of situation (context) are we in? What kinds of actions does it require of us? What kinds of action does it afford us? The ‘background’ to ‘good’ communication: feelings of fear, anger, resentment, the erosion of trust, the dissipation of vitality — the courage to ‘speak out’: $ $ $ $ $ If it is the case, as I have supposed, that ‘good’ communication depends upon people being able to have the right kinds of spontaneous bodily responses to each other’s utterances ‘at the ready’, so to speak, then, if that is not the case, kinds of consequences will ensue. ‘Good’ communication works smoothly in terms of our fulfilling each other’s anticipations and expectations – shared anticipations and expectations that we have all developed from growing up, with similar aims, in similar surroundings (and so on). Indeed, there are in the background to all our communications are a set of what we might call normal expectations: questions receive answers; requests are satisfied; refusals are followed by justifications; greetings are answered with a return greeting; apologies are normally accepted; accusations lead either to a denial or a confession; and so on. Central to them is our expectation, as autonomous, adult individuals, that we are free to act as we see fit, as long as we can give good reasons for our actions, i.e., reasons which can be traced back and linked with the values we all share in our community. Being told we cannot do something, irrespective of any of the good reasons we give for doing it, not only arouses resentments at the attack on our freedoms. $ It can also arouse a feeling in us that the refuser – to whom we have given our good reasons – cannot be trusted. He/she is not a part of the same community as us; they do not share our values. $ As we explore the consequences of ‘bad’ communication, of failures, we will also come to understand the conditions required to afford ‘good’ communication. $ As I have already indicated above, when we ask a question, we already have sense, i.e., an embodied expectation, of what an answer to it will be like, and it will be against the background of that anticipation that we will judge whether our respondent is actually giving us an ‘answer’ or not – we all know of Jeremy Paxman’s 12 repeatings of a question to Michael Howard, and our 12 hearings of him not answering it. $ $ Let us now turn to a request: I ask for help. It is refused, full stop. The normal expectation is – unless a good justification for refusal is given – that the other will help; the beggar on the street relies of being able to tear at our heart with their requests for help; we feel our sense of failure to fulfill an obligation as we walk past unresponsive. But there can be further consequences: We make a reasonable appeal to a bureaucrat the easement of a regulation – you even give them the reason that it will make everything run much more efficiently. They refuse. You feel a shattering of the normal expectancies making for human affiliation: giving good reasons. As a consequence, (1) you can feel a certain loss of self-confidence – you don’t know how to express yourself in a sufficiently eloquent manner; (2) you can feel a good deal of anger – you have not been afforded the basic human right of being properly listen to and responded to; (3) you can habour the lack of trust created – thus, in the future, not seek to ask that bureaucrat ever again for help; and so on. $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ What can give us courage to ‘speak out’ in a situation? First, having ‘good reasons’ which you know link to the values all in the situation share, and which you can express in terms they will understand (i.e., that works in terms of the relevant background normal expectancies). Second, knowing all the alternatives that have been previously mooted, and having good reasons for rejected them here (with a similar ability to express them). Thirdly, have taken the trouble oneself ‘to walk the streets of the new city’, so to speak – in other words, your good reasons can be articulated, not just in terms of theories, suppositions, etc., but in terms of an actual ‘in touchness’ with the concrete details of the situation in question. Speaking with the ‘courage of one’s convictions’ can ‘move’ others, i.e., reorient them, toward ‘seeing’ the circumstances that all occupy ‘in anew light’. What can give us courage ‘to act in the moment’? The situation here is a bit similar to the championship tennis player running for a winning shot. The player makes the shot: (1) because they have embodied the relevant ‘readinesses’ as a result of hours of ‘on court’ and ‘off court’ practice, plus hours of playing good opponents, all of whom have ‘called out’ from them, spontaneous responses that no other activity could call out. (2) As a result, the player has an embodied sense of the complex unity formed by the nexus of influences at work in both his/herself and the dynamics of their surrounding situation. (3) In such circumstances, they simply and directly, with all but no conscious deliberation, answer to the unfolding calls they sense, as they change moment-by-moment, as a result of their own moving around on the court. (4) And strangely, it is only in their moving around that the relevant ‘calls’ arise. In our work-life situations, we can find the same kind of courage, the same kind of poise and calmness in the face of chaotic complexity, if we can sense our (invisible) relations to all the others around us. For that sense can arouse in us the action guiding anticipations that will ready us, in anticipation, to respond to how they respond, to our actions. What we call ‘acting rationally’ is being able to act in ways in which we can account to others for our actions, i.e., give them good reasons, thus to show them that we acted with concern for many, many relational details in our ‘doings’.