Beyond the World of Words

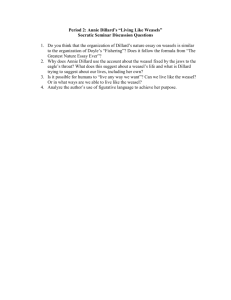

CONFERENCIA PLENARIA

Beyond the World of Words:

Edward Abbey, Annie Dillard, and Jorge Luis Borges

Kenichi Noda

Rikkyo University

Tokyo, Japan

Let us call this region beyond our representations---this ever-censored part---finititude,

….. (Yves Bonnefoy, “Image and Presence”)

This paper chiefly aims to offer and discuss the idea of Post-Romanticism for the purpose of clarifying what we inherit from the Romantic idea about nature mainly emerged and shaped around the early nineteenth century. Literary Romanticism, in one sense, provided us with several new and significant perspectives upon the human attitude toward the natural world.

One of the most important things to be reminded here is the invention of an epistemological device for changing things in nature or natural objects into symbols that represent or refer to a transcendental truth. Romantics found that natural objects are potential symbols for something eternal, though things themselves are finite. But this theological and philosophical device undoubtedly set a limit upon our 20 th

and 21 st

century-approach to nature because of its excessively religious and metaphysical implication.

I

“Nature couldn’t do without God, and God apparently couldn’t do without nature”

Once there was a time, which is called the age of Romanticism, when many poets and writers conceived thus: things in nature or natural objects are important because they are able to refer to the transcendental truth, or infinitude, or eternity or whatever. In other words, natural objects, whether they be rocks, plants, or animals, were regarded as epistemological routes to accessing religious truth and divinity. Romantic poets and writers somehow hoped or desired to make things speak for or refer to something eternal and immortal, something that is transcendental. Things were a frame of reference to be remarked so as to reach a less physical,

1

more metaphysical sphere of meaning. The idea of Romantic correspondence between human and nature took its shape in the idea that things are just the shadows or mirrors of “divine things,” if we borrow the title of a book by Jonathan Edwards, an American theologist in 18 th century.

After this kind of correspondential relationship between things and transcendental truth being shaped and established, any single object or thing in the natural world turns out to be capable of referring to infinitude. Moreover, any single object refers, as well, to a whole world that it consists a part of, and that includes innumerable interrelated objects, a web of things. Thus, Romanticism discovered an underlying oneness beneath the multiform of natural objects [ONE in MANY], and it sought for a radical bond or a system of representation and religious linkage of things, infinitude, and human being. It thus created, or invented, a system of representational relationship among them.

However, after Romanticism, things have ceased referring infinitude: they just refer to finitude or the finite or “presence,” not eternity nor “representation.” They have become fragmentary because they lost a whole system of representation that Romantics conceived or invented. “Presence” means “ just being-out-there,” and the particularity of a particular object at “such-and-such a time” in “such-and-such a place,” which Annie Dillard, for example, termed as “the scandal of particularity” in her book, Pilgrim at Tinker Creek . Things have lost their bonds with eternity and wholeness that Romantics created just a few centuries ago. In that sense, we are in the era of Post-Romanticism.

Physics/Meta-physics, the Natural/the Super-natural, and View/Vision

What we briefly observed so far in Romanticism is a newly developed or invented machinery of thought that makes physics (Nature) turn into meta-physics (Super-nature): views into vision, signs into symbols, sight into insight, land into landscape, the natural into the supernatural, to name a few. The latter part of each dichotomy indicates the specific aspect of the representational whole. This is the mechanism that stimulated an upward and vertical movement of thought for getting access to meta-physics. This is in sharp contrast with the ecological and horizontal relationship with those beings and things, not to mention that

Christianity was, in this way, re-structured upon that machinery that is called Romantic idea of correspondence.

The Romantic idea of correspondence, this vertical-upward movement for the

2

supernatural and metaphysics is the product of natural theology lying behind Romanticism.

Thus, as Lynn Barber showed in her book, The Heyday of Natural History 1820-1870,

Shakespeare’s well-known phrases quoted from

As You Like It were often mentioned in terms of natural theology .

Find tongues in trees, books in the running brooks,

Sermons in stones, and good in everything. (William Shakespeare, As You Like It .)

Strictly speaking, Shakespeare was neither a Romantic nor a pre-Romantic, but he just foresaw a new idea arising that things or natural objects become symbols. The similar development was observed in the United States in the nineteenth century. In regard to the intellectual situation in which American landscape painting was placed, art historian, Barbara

Novak, pointed out as follows:

In the early nineteenth century in America, nature couldn’t do without God, and God apparently couldn’t do without nature. By the time Emerson wrote Nature in 1836, the terms “God” and “nature” were often the same thing, and could be used interchangeably.

“Nature couldn’t do without God, and God apparently couldn’t do without nature,” and “the terms “God” and “nature” could be used interchangeably,” Novak said. Perry Miller,

American historian, termed this as “Christianized naturalism,” and other scholars named something like “secularized Christianity,” or “Natural Supernaturalism,” and so on.

If the linkage between nature and God is necessary in developing Romantic idea of correspondence, the following two questions are arguable enough:

Question 1: Is nature poetry actually the poetry about nature? Romantic nature poetry might be regarded a variant of religious poetry because its subject matter lies NOT in natural objects but in the more-than-natural/physical world.

Question 2: Is landscape painting actually the painting about nature?

The possible answers to these questions are the same: both nature poetry and landscape painting are the so-called sister arts to find out God, literally or figuratively, in or through the

3

natural world, and the natural objects depicted in those works are carefully selected and described solely for achieving the purpose. If so, either nature poetry or landscape painting does not necessarily intend to describe nature for its own sake.

Nature for Its Own Sake

Nature poetry and landscape painting are a newly invented genres of art whose existence is justified only by the fact that the natural objects depicted in the works refer to the super-natural or meta-physical. They suggest that the real significance of physics or nature is given by the deep relationship with meta-physics or the supernatural. In other words, both nature and landscape described to function as representation, not as physical reality, in the works of Romantics.

That’s why Yves Bonnefoy, a French poet in the late 20 th

century, repeatedly claimed:

“Let us call this region beyond our representations—this ever-censored part—finititude.”

Romantics were less concerned with finititude than with infinititude because natural theology was firmly embedded in their work. Yes, “finititude” was, and has been the very thing that is beyond “our representations, ” as Bonnefoy suggests. So the physicality of physics has been censored and suppressed. Romanticism preferred nature as symbol to nature as sign.

Disregarded by Romantics was “finititude” and “presence,” that is, how they actually are, Bonnefoy insists. Again, Romantics were less interested in the real feature than the religiously overlying significance of the natural world. Ralph Waldo Emerson, a leader of

American Romanticism, wrote about how Romantic poets are and should be indifferent to the outer natural objects in his journal, the passage of which gives us a quite succinct account of the Romantic idea about natural objects:

But every man may be (as some men are) raised to a platform whence he sees beyond sense to moral and spiritual truth; when he no longer sees snow as snow, or horses as horses, but only sees or names them representatively, for those interior facts which they signify. This is the way prophets, this is the way poets use them. And in that exaltation small and great are as one, the mind strings worlds like beads upon its thought.

4

As Emerson quite honestly says, a true Romantic poet “no longer sees snow as snow, or horses as horses” even when he describes those things in his work. What is important for a poet is not those natural objects like snow or horses, but “ those interior facts which they signify,” not those “exterior facts”( Italics mine). This explains how Romantics are less concerned with those natural objects, how insignificant it is for them to observe those external facts rightly and objectively. They don’t see snow as snow, horses as horses: they see something else when they see those things! Their attention and focus of interest are entirely upon what things and objects “representatively” and symbolically means and refers.

Emerson’s view of poet described in this journal entry tells us that Romantic nature poets are not interested in describing the natural world itself.

Edward Abbey, one of the representative nature writers in the 20th century, writes about this same issue in his own way:

Through naming comes knowing; we grasp an object, mentally, by giving it a name—hension, prehension, apprehension. And thus through language create a whole world, corresponding to the other world out there. Or, we trust that it corresponds. Or perhaps, like a German poet, we cease to care, becoming more concerned with the naming than the things named; the former becomes more real than the latter. And so in the end the world is lost again. No, the world remains—those unique, particular, incorrigibly individual junipers and sandstone monoliths—and it is we who are lost. Again. Round and round, through the endless labyrinth of thought—the maze.

Amazing, says Waterman, going to sleep.

(Edward Abbey, “Terra Incognita: Into the Maze,” p. 257)

According to Abbey, we “create a whole world” by using language, but we still believe that the world we create rightly corresponds to “the other world out there,” which means the natural world surrounding us. Yet, then, we become more concerned with the naming, and less concerned with the things named. Moreover, the representation or the represented becomes more real than the real things or objects. Thus, Abbey strongly indicates the pitfall of language and representation which Emerson, for example, and Romantics in general didn’t notice. “A whole world,” which Abbey calls, is the world linguistically created by poets and

5

writers. A world of representation. This might be also called “textualized nature,” by which

Romantics believed its authenticity.

However, as Abbey suggests, the textualized nature is not the same with the real nature, and he never believes it is so, because he is not a Romantic, but because he is a

Post-Romantic who clearly knows the difference between the textualized and the real, between the represented and the presence. His emphasis upon uniqueness, particularity, and individuality of the natural objects in the latter part of the quoted passage explicitly reveals that his approach is an attempt to avoid the natural symbolism.

Edward Abbey is one of the most representative contemporary nature writers (though he has been dead since 1989) with a discriminating and critical eye for the Romantics’ view of nature and language. In other words, he stresses that the natural world is, and should always be “beyond the world of words,” using his words in “Author’s Introduction” in the same book.

Romantics’ frequent use of the images of nature led to a certain style of literary description of the natural world, and we inherit a great deal from the tradition. But we need to pay more attention to what literary Romanticism lacks, that is, to the real world “beyond the world of words.” Otherwise, “the world is lost again,” as Abbey warns us. “No,” he adds, “the world remains—those unique, particular, incorrigibly individual junipers and sandstone monoliths—and it is we who are lost.” Abbey’s works includes a lot of important idea about how to rethink and reestablish the relationship between our language and the natural world, which leads us to the Post-Romanticism.

Toward the World of Here/Now

Edward Abbey suggests that we should be more careful about how the relationship between our language and the natural world should be. More simply: a poet should see snow as snow, horses as horses if she or he chooses NOT to be anthropocentric. What constitute the

Post-Romanticism are: The uniqueness, particularity, and individuality of the natural objects.

Annie Dillard’s Pilgrim at Tinker Creek is such a Post-Romanticist’s work, too. She is quite similar to Abbey in her concern with the relationship between language and natural objects.

6

When her doctor took her bandages off and led her into the garden, the girl who was no longer blind saw “the tree with the lights in it.” It was for this tree I searched through the peach orchards of summer, in the forests of fall and down winter and spring for years.

Then one day I was walking along Tinker Creek thinking of nothing at all and I saw the tree with the lights in it. I saw the backyard cedar where the morning doves roost charged and transfigured, each cell buzzing with flame. I stood on the grass with the lights in it, grass that was wholly fire, utterly focused and utterly dreamed. It was less like seeing than like being for the first time seen, knocked breathless by a powerful glance. (Annie Dillard,

“Seeing,”

Pilgrim at Tinker Creek , p.33)

The first part of this passage tells a story about a congenitally blind girl who recovered her eyesight through surgical operation. What she saw for the first time in her life is, the girl said,

“the tree with the lights in it.” This story that Annie Dillard read in some book is one of the several important stories or anecdotes which the author cherishes and repeatedly returns to in this book.

“The tree with the lights in it”: this frequently-repeated and unique image of the tree is quite important in thinking about Annie Dillard’s approach to the natural world. This image profoundly attracts the author because it makes her notice that an act of “seeing” is made possible by the light shed upon the objects, and that our visual experience is always with the lights. So when you say, “I can see,” you see not only objects but also “the lights” in them.

Through this story Annie Dillard discovered the simple fact that objects and lights are inseparable in our visual experience. The blind girl’s first comment on what she saw, “the tree with the lights in it,” is inspiring enough for the author because we usually don’t notice that we see the lights when looking at a tree, or that we see the lights as well as a tree. Without light we cannot see anything: this simple fact leads this author to an epistemological dilemma.

Why don’t we notice the lights when looking at a tree though the girl with a newly-acquired eyesight discovered? What prevents us not to do so? This question brings about an epistemological problem about the relationship between human and the natural environment. We often don’t see when looking at something because the things are not always the objects for seeing but the ones just for recognition. We often don’t see the trees even they are right before our eyes because what we need to get from those trees is just an epistemological information, a label, not their details and reality. Our seeing is a very

7

superficial seeing in our daily life.

Instead, Annie Dillard’s motif of “the tree with the lights in it” is an experimental attempt to deepen our visual experience into its own wholeness. It’s just like an impressionist painting always holding the lights on canvas with the shapes and colors of things. “[T]he tree with the lights in it” is not just an epistemological information, but an image of the wholeness of the tree, and this is what the author searched for. And she finally encountered, she writes, the tree, backyard cedar, and the grass “with the lights in it.” The grass she saw is described as something like “wholly fire, utterly focused and utterly dreamed.” The objects we see in

Annie Dillard’s sense are not concepts, nor symbols, but the things themselves, which strongly impress us with a paradoxical sense of being in a dream: “utterly focused and utterly dreamed.”

Also, this experience of seeing is so intense for the authors that it brings about the reversal of the relationship between the subject and the object as the author writes as “[I]t was less like seeing than like being for the first time seen.” This highly impressive scene reveals one of the most profound correspondential experiences with the natural world that have ever been written. Especially, the collapse or the reversal of the distinction between subject and object displays how the author encountered the oneness caused by the correspondence between human and the natural world. However, we need to confirm that this experience of

Annie Dillard is Post-Romantic one, not Romantic, for the scene of “the tree with the lights in it” informs us that the door for this correspondential oneness is not opened toward eternity as often was in the Romantic writings. Surely, a door is opened. Dillard writes about “the great door” like this:

I had thought, because I had seen the tree with the lights in it, that the great door, by definition, opens on eternity. Now that I have “patted the puppy”---now that I have experienced the present purely through my senses---I discover that, although the door to the tree with the lights in it was opened from eternity, as it were, and shone on that tree eternal lights, it nevertheless opened on the real and present cedar. It opened on time:

Where else? (p. 80)

Annie Dillard emphasizes, as it were, more the Post-Romantic-ness than the Romantic-ness by focusing “the present” time experienced “through [my] senses.” “The great door,” she

8

writes, “opened on the real and present cedar. It opened on time: Where else?” Yes, the door opened on time, opened on the temporal, opened on Here/Now. This is one of the conspicuous features that distinguishs Post-Romanticism from Romanticism. As with the case of Abbey, the uniqueness, particularity, and individuality of the natural objects account for the Dillard’s approach.

The World of Funes

Jorge Luis Borges’ short story entitled “Funes, the Momorius” is an interesting story because this work shares the Post-Romantic view of nature and language with Edward Abbey and

Annie Dillard. This story is a memoir about a 19-year-old young man called Ireneo Funes, who had an extraordinary memory which he could not get off from his brain. He confessed:

“I have more memories in myself alone than all men have had since the world was a world.”

He suffered “an unusable mental catalogue of all the images of memory” compiled like a

“garbage disposal” and for him “the present was almost intolerable it was so rich and bright.”

Although this is a story about a man with too much memory, a story about insomnia, what afflicted him most is the incessant assault with the “present” moments of time, so rich and bright.

He was, let us not forget, almost incapable of general, platonic ideas. It was not only difficult for him to understand that the generic term dog embraced so many unlike specimens of differing sizes and different forms; he was disturbed by the fact that a dog at three-fourteen (seen in profile) should have the same name as the dog at three-fifteen

(seen from the front). (Jorge Luis Borges, “Funes, the Memorious,” p. 42)

Funes is placed in and obsessed with the excessive present moment of time, Here/Now, as

Annie Dillard is. And his extravagant memory is due to his lack of “general, platonic ideas.”

His life was surrounded by “a multiform world which was instantaneously and almost intolerably exact.” Who is Ireneo Funes? He is the man who looks at a dark passion flower as

“no one has ever looked at such flower.” The man who does not perceive the sameness of a dog at three-fourteen with a dog at three-fifteen. The “multiform world” that Funes witnesses has a great resemblance to Annie Dillard’s “tree with the lights in it” and “grass that was

9

wholly fire.” Both writers decidedly suggest us that there is a “multiform world,” a world of

MANYness, of noise and chaos, which is to be called the real world, and it is beyond the world of words, beyond our representation. Borges writes:

Without effort, he[Funes] had learned English, French, Portuguese, Latin. I suspect, nevertheless, that he was not very capable of thought. To think is to forget a difference, to generalize, to abstract. In the overly replete world of Funes there were nothing but details, almost contiguous details.

Yes, “To think is to forget a difference,” as the author succinctly writes, and to think is “to generalize” and “to abstract” by means of language. Abstraction and generalization are the essential and necessary functions of human language, through which our intellectual activity is made possible. But Borges wrote this story about Funes. It is not because the author was interested in a certain kind of pathological issue regarding language, but because he was deeply interested in thinking about what it means for us to have language, to use it, to think by means of it. As Borges says, “[t]o think is to forget a difference,” and to think is to forget “the overly replete world of Funes” fraught with “nothing but details, almost contiguous details.”

Borges writes:

We, in a glance, perceive three wine glasses on the table; Funes saw all the shoots, clusters, and grapes of the vine.

This passage clearly illustrates the difference between Funes and us in sensitivity and attitude toward the world and nature. I think that Funes should not be considered as an exceptional insomnious person. As with Edward Abbey and Annie Dillard, Borges ask us pay more attention to the world, to the natural world, in a quite different way. To think about the relationship between human and the natural world is to think more about our language because language might prevent us from contacting the world itself, “a multiform of world,” the real world, and the thing itself.

The writers I mentioned are, as it were, can be called Post-Romantic writers because all of them are very conscious about the radical gap between the represented nature and the real

10

nature. And they know, and we should know, too, that the moment Romanticism opened up its eye for the natural world, paradoxically it lost the sight of the otherness of the other world.

We should ask again and again: whether the world we linguistically create “correspond[s] to the other world out there,” as Edward Abbey points out. I would like to refer Abbey’s well-known statement before concluding my lecture:

I want to be able to look at and into a juniper tree, a piece of quartz, a vulture, a spider, and see it as it is in itself, devoid of all humanly ascribed qualities, anti-Kantian, even the categories of scientific description.

This should be the manifest of the Post-Romanticism, I think. If time permits, I would like to cite two more instances for rethinking about the subject I have discussed so far:

Alain Robbe-Grillet

To assert that he speaks for things, with them, in their heart , comes down, under these conditions, to denying their reality, their opaque presence: in this universe populated by things, they are lo longer anything but mirrors for a man that endlessly reflect his own image back to him. Calm, tames, they stare at man with his own gaze.

(Alain Robbe-Grillet, “Nature, Humanism, Tragedy,” For a New Novel: Essays on Fiction , p.69.)

Onno Dag Oerlemans

Theorizing an understanding of the "Other" has been a major impetus of philosophy and literary criticism this century, especially over the past several decades. Even a casual survey of such writing (think of Levinas, Derrida and Foucault), though, reveals that the concept of the Other is commonly assumed to include only the human, the foreignness of other individuals, races or cultures. Outside of explicitly environmentalist writing, and perhaps, indirectly, Heidegger's writing on "Being" (which need not be specifically human), the

Otherness of the natural world in general, and animals in particular, has been overlooked.

While those who write on environmental and animal rights issues often make use of the ethical and political implications of abstract and human-centered notions of otherness, there is

11

no real scholarly dialogue between those with ecological concerns and those who speak for

(or as) excluded or oppressed voices within political or literary realms.

(Onno Dag Oerlemans, ““The Meanest Thing That Feels”: Anthropomorphizing Animals in

Romanticism,”

Mozaic , vol. 27, 1994.

Works Cited

Abbey, Edward. Desert Solitaire: A Season in the Wilderness . New York: Touchstone Book,

1968.

Barber, Lynn. The Heyday of Natural History 1820-1870 . New York: Doubleday & Company,

Inc., 1980

Bonnefoy, Yves. The Act and the Place of Poetry: Selected Essays . Chicago and London: The

University of Chicago Press, 1989.

Borges, Jorge Luis. “Funes, the Memorious,” A Personal Anthology . New York: Grove Press,

Inc., 1967.

Miller, Angela. “Everywhere and Nowhere: The Making of the National Landscape.”

American Literary History , Vol. 4, No.2: Summer, 1992.

Novak, Barbara. Nature and Culture: American Landscape and Painting 1825-1875. New

York: Oxford University Press, 1980.

Oerlemans, Onno Dag. ““The Meanest Thing That Feels”: Anthropomorphizing Animals in

Romanticism.”

Mozaic , Vol. 27, 1994.

Orth, Ralph H. and Alfred R. Ferguson, eds. The Journals and Miscellaneous Notebooks of

Ralph Waldo Emerson , Vol. XIII, 1852-1855 . Cambridge, Mass and London: The Belknap

Press of Harvard University Press, 1977.

Robbe-Grillet, Alain. “Nature, Humanism, Tragedy.” For a New Novel: Essays on Fiction.

Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University Press, 1989.

Quotes

Yves Bonnefoy

[Much will therefore be lost from beings and objects evoked in this manner, and in particular their own inner relationship with themselves, their very act of being, this right they have to be here, in spite of the dreamer and in conflict with his idea of the world, albeit in agreement

12

with the very necessity he denies.] Let us call this region beyond our representations--this ever-censored part--finititude, since if we knew how to listen to it, it would assign to us our limits.

(Yves Bonnefoy, ““Image and Presence”: Inaugural address at the College de France,”

The

Act and the Place of Poetry: Selected Essays, p. 163)

For as Hegel has shown, seemingly with relief, speech can retain nothing that is immediate.

(Yves Bonnefoy, “The Act and the Place of Poetry,” p. 107)

Lynn Barber

[They did not need to, because] natural history had a far superior claim to attention, one that made it automatically more rational and respectable than all the other sciences put together.

This was natural theology, the spiritual exercise that enabled one to look ‘through Nature up to Nature’s God’ and to

Find tongues in trees, books in the running brooks,

Sermons in stones, and good in everything. (William Shakespeare, As You Like It .)

(Lynn Barber, The Heyday of Natural History 1820-1870 , 1980.)

In the early nineteenth century in America, nature couldn’t do without God, and God apparently couldn’t do without nature. By the time Emerson wrote

Nature in 1836, the terms

“God” and “nature” were often the same thing, and could be used interchangeably. The

Transcendentalists accepted God’s immanence. More orthodox religions, which had always insisted on a separation of God and nature, also capitulated to their union. A “Christianized naturalism,” to use Perry Miller’s phrase, transcended theological boundaries, so that one could find “sermons in stones, and good in every thing,” “Nature,” wrote Miller, “somehow, by a legerdemain that even so highly literate Christians as the editors of The New York Review could not quite admit to themselves, had efectually taken the place of the Bible. … . .”

(Barbara Novak, Nature and Culture , p.3)

The rule of positive and superlative is this. As long as you deal with things from your common sense, or as other people in the street, call things by their right names. But every man

13

may be (as some men are) raised to a platform whence he sees beyond sense to moral and spiritual truth; when he no longer sees snow as snow, or horses as horses, but only sees or names them representatively, for those interior facts which they signify. This is the way prophets, this is the way poets use them. And in that exaltation small and great are as one, the mind strings worlds like beads upon its thought. The success with which this is done can alone determine how genuine is the inspiration.

( The Journals and Miscellaneous Notebooks of Ralph Waldo Emerson , Vol. XIII, 1852-1855 , edited by Ralph H Orth and Alfred R. Ferguson. Cambridge, Mass and London: The Belknap

Press of Harvard University Press, 1977, p. 392.)

Edward Abbey

Through naming comes knowing; we grasp an object, mentally, by giving it a name--hension, prehension, apprehension. And thus through language create a whole world, corresponding to the other world out there. Or, we trust that it corresponds. Or perhaps, like a German poet, we cease to care, becoming more concerned with the naming than the things named; the former becomes more real than the latter. And so in the end the world is lost again. No, the world remains--those unique, particular, incorrigibly individual junipers and sandstone monoliths--and it is we who are lost. Again. Round and round, through the endless labyrinth of thought--the maze.

Amazing, says Waterman, going to sleep.

(Edward Abbey, “Terra Incognita: Into the Maze,” p. 257)

What I have tried to do then is something a bit different. Since you cannot get the desert into a book any more than a fisherman can haul up the sea with his nets, I have tried to create a world of words in which the desert figures more as medium than as material. Not imitation but evocation has been the goal. (Edward Abbey, “Author’s Introduction,” p. xii)

Annie Dillard

When her doctor took her bandages off and led her into the garden, the girl who was no longer blind saw “the tree with the lights in it.” It was for this tree I searched through the peach orchards of summer, in the forests of fall and down winter and spring for years. Then one day I was walking along Tinker Creek thinking of nothing at all and I saw the tree with

14

the lights in it. I saw the backyard cedar where the morning doves roost charged and transfigured, each cell buzzing with flame. I stood on the grass with the lights in it, grass that was wholly fire, utterly focused and utterly dreamed. It was less like seeing than like being for the first time seen, knocked breathless by a powerful glance. (Annie Dillard, “Seeing,”

Pilgrim at Tinker Creek , p.33)

I had thought, because I had seen the tree with the lights in it, that the great door, by definition, opens on eternity. Now that I have “patted the puppy”---now that I have experienced the present purely through my senses---I discover that, although the door to the tree with the lights in it was opened from eternity, as it were, and shone on that tree eternal lights, it nevertheless opened on the real and present cedar. It opened on time: Where else? (p. 80)

Jorge Luis Borges

He told me: I have more memories in myself alone than all men have had since the world was a world. And again: My dreams are like your vigils. And again, toward dawn: My memory, sir, is like a garbage disposal.

(Jorge Luis Borges, “Funes, the Memorious,”

A Personal

Anthology , p. 40)

He was, let us not forget, almost incapable of general, platonic ideas. It was not only difficult for him to understand that the generic term dog embraced so many unlike specimens of differing sizes and different forms; he was disturbed by the fact that a dog at three-fourteen

(seen in profile) should have the same name as the dog at three-fifteen (seen from the front).

(Jorge Luis Borges, “Funes, the Memorious,” p. 42)

Without effort, he had learned English, French, Portuguese, Latin. I suspect, nevertheless, that he was not very capable of thought. To think is to forget a difference, to generalize, to abstract.

In the overly replete world of Funes there were nothing but details, almost contiguous details.

(p.43)

For nineteen years, he said, he had lived like a person in a dream: he looked without seeing, heard without hearing, forget everything---almost everything. On the falling from the horse, he lost consciousness; when he discovered it, the present was almost intolerable it was so rich

15

and bright; the same was true of the most ancient and most trivial memories. (p. 40)

We, in a glance, perceive three wine glasses on the table; Funes saw all the shoots, clusters, and grapes of the vine. (p.40)

I remember him (I scarcely have the right to use this ghostly verb; only one man on earth deserved the right, and he is dead), I remember him with a dark passionflower in his hand, looking at it as no one has ever looked at such a flower, though they might look from the twilight of day until the twilight of night, for a whole life long. (p. 35)

He was the solitary and lucid spectator of a multiform world which was instantaneously and almost intolerably exact. ( Ibid .)

Alain Robbe-Grillet

To assert that he speaks for things, with them, in their heart , comes down, under these conditions, to denying their reality, their opaque presence: in this universe populated by things, they are lo longer anything but mirrors for a man that endlessly reflect his own image back to him. Calm, tames, they stare at man with his own gaze.

(Alain Robbe-Grillet, “Nature, Humanism, Tragedy,” For a New Novel: Essays on Fiction , p.69.)

Angela Miller

This landscape of self was an uncolonized place of freedom and potential anarchy whose contours reflected the perceiving subject more than any shared communal identity. These two forms of landscape---the one aesthetically and ideologically constructed, the other experientially wrought and shaped by a resistance to public mythologies---confronted and contradicted one another most forcibly at various points in the nineteenth century.

(Angela

Miller, “Everywhere and Nowhere: The Making of the National

Landscape,“

American Literary History , Vol. 4, No.2: Summer, 1992, p. 221)

Onno Dag Oerlemans

16

Theorizing an understanding of the "Other" has been a major impetus of philosophy and literary criticism this century, especially over the past several decades. Even a casual survey of such writing (think of Levinas, Derrida and Foucault), though, reveals that the concept of the Other is commonly assumed to include only the human, the foreignness of other individuals, races or cultures. Outside of explicitly environmentalist writing, and perhaps, indirectly, Heidegger's writing on "Being" (which need not be specifically human), the

Otherness of the natural world in general, and animals in particular, has been overlooked.

While those who write on environmental and animal rights issues often make use of the ethical and political implications of abstract and human-centered notions of otherness, there is no real scholarly dialogue between those with ecological concerns and those who speak for

(or as) excluded or oppressed voices within political or literary realms.

(Onno Dag Oerlemans, “The Meanest Thing That Feels”: Anthropomorphizing Animals in

Romanticism,” Mozaic , vol. 27, 1994.

17