Assignment#1

advertisement

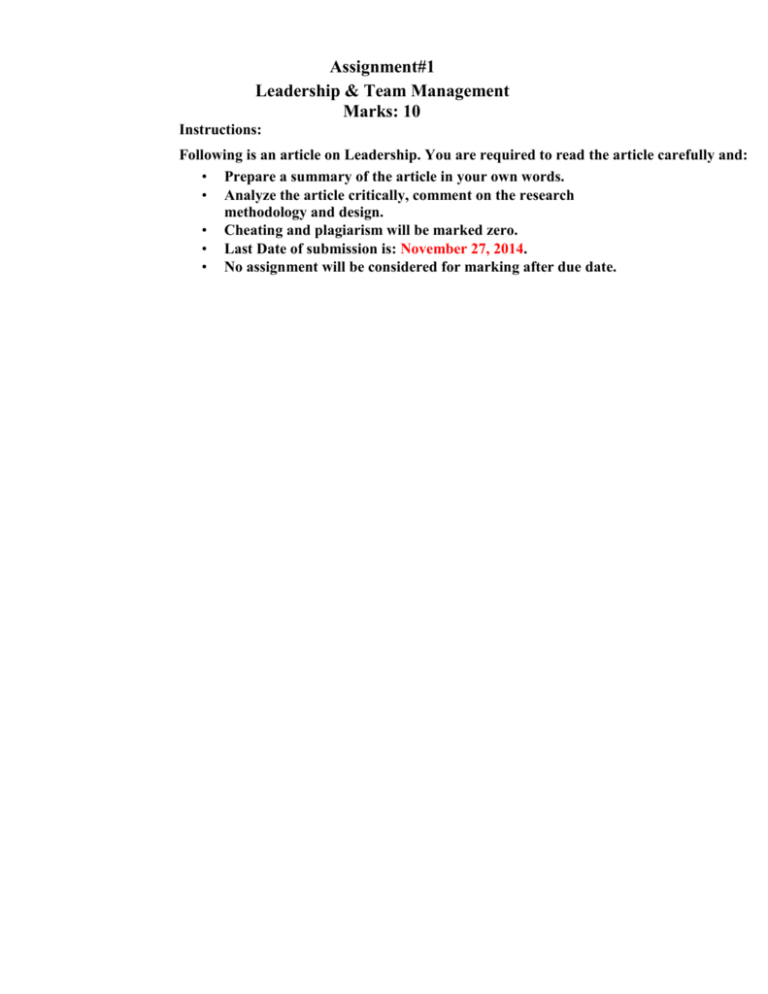

Assignment#1 Leadership & Team Management Marks: 10 Instructions: Following is an article on Leadership. You are required to read the article carefully and: • Prepare a summary of the article in your own words. • Analyze the article critically, comment on the research methodology and design. • Cheating and plagiarism will be marked zero. • Last Date of submission is: November 27, 2014. • No assignment will be considered for marking after due date. How Leaders Woo Followers in the Romance of Leadership Judy H. Gray Monash University, Melbourne, Australia Iain L. Densten Lancaster University, UK INTRODUCTION Prior to the development of the romance of leadership theory (Meindl & Ehrlich, 1987; Meindl, Ehrlich, & Dukerich, 1985), the importance of follower perspectives of leadership were largely overshadowed by the sheer volume of research which attributed organisational successes and failures primarily to the behaviors and personalities of leaders. As a social constructionist approach, the romance of leadership refers to followers overestimating the influence of leadership on organisational performance (Meindl, 1995). While not denying the importance of follower implicit theories of leadership, the current paper contends that leaders too play an active although subtle role in the development of follower perceptions of leaders and thereby contribute to the implicit theories of leadership held by followers. The study advances our understanding of the causes of leader attributions which Meindl and Ehrlich (1987) suggested should be explored to validate the romance of leadership. This study examines empirically the impact of social desirability biases (i.e. self-deception and impression management) on leaders’ perceptions of their leadership behaviors in order to better understand the origins of the romance of leadership and to clarify how this process occurs. Social desirability biases refer to the tactics leaders use to present themselves in a socially approved manner. We contend that leaders deceive themselves through the process of self-deception. At the same time, they project and transmit their biases to cultivate and perpetuate a favorable interpretation of their leadership by others using impression management. In other words, leaders have romantic views of their own leadership (self-deception) and they attempt to convince their followers to romanticise about leadership (impression management). In terms of the romance of leadership theory (Meindl, 1998), we suggest that leaders utilise social desirability biases to influence followers so that followers will attribute organisational successes to their leadership. The corollary is that leaders downplay negative aspects of their leadership so that they are not blamed by followers for negative organisational outcomes. In other words, the use of social desirability biases by leaders suggests that leaders have a tacit motive to achieve greater leverage in influencing follower thinking so that leaders can take credit for organisational successes and are not unduly blamed for failures. Therefore, leaders consciously and unconsciously contribute to the construction of leader images by followers in a way that produces romantic notions of leadership on the part of followers. Thus, the study proposes that leaders are the initiators of the romance of leadership and thereby “woo” followers. LITERATURE REVIEW The Follower-Centric Perspective The follower-centric perspective of leadership suggests that followers hold implicit theories or preconceived notions that underpin their “romanticised beliefs” about leadership (Meindl et al., 1985). The extant literature on implicit leadership theories (e.g. Den Hartog, House, Hanges, Ruiz-Quintanilla, & Dorfman, 1999; Epitropaki & Martin, 2004) elucidates follower perceptions of leader attributions. Several studies have attempted to identify the ascribed characteristics of implicit leadership theories (Den Hartog & Koopman, 2005; Muller & Schyns, 2005). For example, Offermann, Kennedy, and Wirtz (1994), in a study to describe the content of implicit theories, identified eight factors, namely: Leader sensitivity, dedication, tyranny, charisma, attractiveness, masculinity, intelligence, and strength. Further classification of these factors has identified positive (e.g. dedication) and negative (e.g. tyranny) attributions (Epitropaki & Martin, 2004). Similarly, Kouzes and Posner (1987) cited several studies which indicated that the leader characteristics most valued by followers are honesty, integrity, and truthfulness. The Leader-Centric Perspective The leader-centric perspective is predicated on the belief that the most important aspect of leadership is the ability to influence the interpretations that significant others give to events and actions (Daft & Weick, 1984). This view asserts that leadership involves “the framing of meaning and the mobilisation of support for a meaningful course of action” (Gronn, 1996, p. 8). Thus, if leaders influence how followers construct images of their leaders, then it follows that leaders would be more inclined to promote the aspects of their leadership behaviors that correspond to the more socially desirable factors such as leader sensitivity and attractiveness and would downplay less socially desirable factors such as tyranny. The research on leader cognitive and behavioral complexity (e.g. Hooijberg, Hunt, & Dodge, 1997) and social intelligence (e.g. Zaccaro, 2002) emphasises that to be effective, leaders need to have a large repertoire of influence tactics and select behaviors that are appropriate to particular social situations. For example, Kenny and Zaccaro (1983, p. 678) suggested that leaders must have the “ability to perceive the needs and goals of a constituency and to adjust [their] personal approach to group action accordingly”. Several studies have demonstrated that when leaders meet group goals and their behaviors correspond to follower implicit theories of “good” leadership, leaders are more likely to be able to influence followers (Kenney, Schwartz-Kenney, & Blascovich, 1996; Nye, 2005). Further, Schyns and Meindl (2005) suggested that it may be easier for leaders to lead followers who have “realistic” expectations (i.e. where there is a high degree of congruence between leaders’ self-expectations and followers’ expectations of their leaders). This contention may provide a powerful explanation for why leaders attempt to influence follower attributions of leadership. In other words, it would be in their own interest for leaders to behave in ways that attract follower approval. Alternatively, leaders would be more likely to win the support of followers if leaders appear to behave in ways that are congruent with follower implicit theories of leadership. A parallel explanation suggests that when leader behaviors match follower prototypes of a leader worthy of influence, then the leader earns the right to be influential (Kenney et al., 1996). Leaders have difficulty influencing followers until they can establish an image of being competent and trustworthy (Chemers, 2002). Image creation is predicated on the implicit theories that leaders have about their own leadership and the images they want to project. Although it has been acknowledged that leaders as well as followers are guided by their implicit theories (Lord, 2005), very little research has been conducted to investigate implicit theories held by leaders. To address this deficiency in the research literature, the current study examines leader self-attributions to further understanding of implicit leadership theories held by leaders. Leader self-attributions are susceptible to distortions, that is, leaders deny common faults or exaggerate personal strengths to project a positive image (Levin & Montag, 1987). Similarly, Donaldson and Grant-Vallone (2002) suggested that leaders accentuate the positive aspects of their leadership and under-report behaviors considered socially inappropriate. These distortions reflect the romantic notions of leadership that leaders hold and can be measured in terms of social desirability biases. Therefore, the current study examines the impact of social desirability biases on leader self-attributions to further understanding of how leaders create illusions of strength and competence (i.e. romantic images). This study examines two social desirability biases; namely, self-deception which relates to “internal” self-attributions of leaders, and impression management which operates as a “tool” to influence the “external” or public image of leaders. Self-Deception Self-deception has been defined as a dispositional or unconscious tendency to have an unrealistic or overly positive self-image (Sackeim, 1983; Zerbe & Paulhus, 1987). Lee and Klein (2002) described self-deception as a stable trait which remains unchanged despite new information that may challenge the person’s self-image. While self-deception is similar to other concepts such as self-serving bias (i.e. positively skewing perceptions to enhance selfimage) and wishful thinking, self-deception is more complex and can involve inten- tional underestimating of a person’s capacity (Litz, 2003). Self-deception is similar to the concept of self-denial of negative attributes (Helmes & Holden, 2003), while the antithesis of self-deception, self-awareness, involves recognition of the strengths and limitations of a person’s own behavior (Day & Lance, 2004). However, self-deception may handicap leader capacity to engage in appropriate relationships with followers because of the lack of awareness of personal shortcomings. Alternatively, there is evidence that well-adjusted individuals engage in self-deception through ignoring minor criticisms, discounting failures, and by having a high expectancy of success (Paulhus, 1986). Consequently, some degree of self-deception may promote a healthy outlook (Zerbe & Paulhus, 1987). Self-deception enables individuals to have more self-confidence, take more risks, and be able to command the loyalty of others more easily (Cowen, 2005). In other words, we suggest that leaders engage in self-deception in order to counter self-doubt and to thereby bolster their sense of self-efficacy which enhances performance through increased confidence and persistence. According to London (2002, p. 67), “leaders are often keenly aware of, and hesitant about, how others view them, especially in terms of how they compare to others [leaders]”. Therefore, while displaying self-confidence, leaders may experience self-doubt resulting from their concerns to meet the ever-changing demands in the environment. Consequently, self-deception is a means of self-defense and acts to allay fears concerning inabilities so that leaders can present a confident public image to followers. Leaders can attain and maintain a positive self-image by asserting that they have mostly positive traits (Moskowitz, 2005). Lord, De Vader, and Alliger (1986) suggested that leaders hold several stereotypic traits (i.e. control, competence, and consistency) that drive their romantic notions of leadership and provide “stereotype traps”, which according to Elsbach (2006) motivate leaders to alter their behaviors to remain consistent with these traits. For example, leaders caught in the “control trap” will attempt to maintain their image of being in charge and running the show (Sutton & Galunic, 1996); if leaders are in the “competency and consistency trap”, they may hide their misjudgments (Hendry, 2002) and behave in a way that is consistent with their ideas. Finally, if leaders are in the “certainty trap”, they will tend to speak of their beliefs and intentions in absolute terms (Clark & Rayne, 1997). Such traps distort the traits that leaders think they are required to display for strong leadership. These traps pro- mote the romantic notions of leadership (e.g. being competent and in control), thereby making it more likely that success would be attributed to the leader as suggested in the romance of leadership (Meindl et al., 1985). Impression Management Rosenfeld, Giacalone, and Riordan (2002, p. 117) viewed impression manage- ment as “the tendency to deliberately over-report desirable behaviors” in order to influence the perceptions of others by controlling the information others receive. The cluster of behaviors which contribute to impression management assists in the development of social identities and influences how people respond and treat each other (Schlenker, 2003). While impression management behaviors may be conscious, for example, when people rehearse in preparation for an interview (Rosenfeld et al., 2002), people are often unaware that they are engaging in such behaviors (Bozeman & Kacmar, 1997). According to Gardner and Cleavenger (1998), leaders use several impression management strategies to project and maintain socially desirable selfimages including: Exemplification behaviors which present the leader as a worthy role model; ingratiation where the leader appears more attractive or likable; self-promotion where the leader appears to be highly competent; and intimidation where the leader uses threats, punishment, or coercive behaviors to benefit the leader at the expense of others. Impression Management and Charismatic Leadership The concept of impression management has been extended to account for the development of charismatic leadership. Impression management has been considered a fundamental element of charismatic leadership (Conger & Kanungo, 1998). According to Turner (1993), to acquire charismatic power, leaders need to impress followers through promises or deeds which fit with the expectations of success and well-being on the part of followers. The leader transforms follower perceptions of risk and in doing so, the leader is perceived as a winner, who is more likely to achieve goals. Rather than supporting a loser, followers prefer leaders they perceive as winners who they assume will improve the odds of success. This suggests that leaders trade on follower expectations through impression management and self-promotion to elicit attributions of charisma from followers. Leader Motives Underpinning Social Desirability Biases Meindl et al. (1985, p. 97) asserted that organisations need leaders who have confidence in their convictions and convey “a sense of efficacy and control”. Therefore, self-deception serves to boost leader self-efficacy in the first instance while impression management is the mechanism by which leaders convey confidence in their own leadership and reinforce an illusion of control. Leaders in particular are driven to use impression management tactics to enhance favorable impressions of themselves and to influence the perceptions of followers so they are regarded as effective leaders who are able to achieve organisational objectives. In some situations, managing impressions may allow leaders to maintain a pretense of confidence and strength. Impression management can be used to highlight self-attributed virtues while minimising deficiencies (Ralston & Kirkwood, 1999). In addition, the use of impression management by leaders improves their subjective social well-being (Rosenberg, 1979). Therefore, the use of impression management allows leaders to attract follower support and build faith in their leadership. Social Desirability Biases and Leadership Behaviors Previous leadership studies have demonstrated that impression management and image building are associated with particular leadership behaviors. For example, impression management has been linked to leader behaviors which encourage followers to trust and be confident in their leaders’ abilities (Densten, 2003). Therefore, in studies using measures of leadership behaviors (e.g. Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Moorman, & Fetter, 1990; Podsakoff, Todor, Grover, & Huber, 1984), we would expect that leader self-perception scores on transformational factors such as Articulates Vision, Fosters Acceptance of Goals, Provides Individual Support, and Provides an Appropriate Model would be inflated by impression management because these factors reinforce favorable self-views of leaders through encouraging followers to perform at their best. In contrast, leader self-perceptions of the use of the more negative aspects of transactional leadership such as contingent punishment behaviors would be deflated because these behaviors could encourage followers to have a negative view of the leader’s contribution to organisational performance. In summary, the romance of leadership has been investigated mainly from a follower-centric perspective. While there is considerable evidence in the literature that leaders actively influence follower perceptions, the current study aims to clarify the origins of the romance of leadership from a leader- centric perspective. The study develops a model to measure to what extent leaders distort their self-attributions of leadership behaviors. We propose that the romantic notions held by leaders act as a precondition for leaders to “woo” followers by positively influencing follower implicit leadership theories through impression management. METHOD The data were drawn from a nation-wide survey where a stratified random sample of 6,500 business executives was selected from the population of 20,563 members of the Australian Institute of Management (AIM) at the time of data collection (May 2004). The sample was stratified on the basis of personal membership categorised by state of origin resulting in a total sample of 2,376 useable responses (a 37% response rate). Sample The majority of respondents were male (73% male), between 40 and 59 years of age (70%). Around half of the sample (53%) were at the top and executive levels (CEO, Chief Operating Officer, Vice President, Director, board level) and 47 per cent were Department Executives, Superintendents, or Plant Managers. Only 20 per cent were in organisations with 1,000 or more employees, while two-thirds (67%) of the sample were at executive level in organisations of 499 or fewer employees. Due to excess statistical power, a large sample size can inflate tests of statistical significance such as estimates of chi-square model fit and standard errors (Loo & Loewen, 2002) and satisfactory models can be rejected because of trivial discrepancies (Bollen, 1989). Consequently, a randomly selected sub-sample of approximately 25 per cent (n = 594) of the total sample (N = 2,376) was used as the basis for initial structural equation calculations (i.e. the derivation sample). In addition, randomly selected sub-samples (approximately 25% of the total sample) were used to cross-validate the results. No statistically significant differences were detected for the results among the sub-samples in this cross-validation process. Consequently, the results are reported for the derivation sample only. Measures A multi-instrument survey was distributed which included measures of leadership, innovation, and social desirability biases. The study relied on gathering cross-sectional data on a single occasion and, consequently, a measure of common method variance was included. Leadership. The Transformational Leadership Scale (Podsakoff et al., 1990) was used to examine six Transformational Leadership factors (number of items and reliabilities are shown in parentheses): Articulates Vision (five items, α = .73), Fosters Acceptance of Goals (four items, α = .73), Intellectual Stimulation (four items, α = .77), Provides Individualised Support (four items, α = .80), High Performance Expectations (three items, α = .75), Provides an Appropriate Model (three items, α = .69), and the Transactional Leadership factors (Podsakoff et al., 1984) of Contingent Reward Behaviors (five items, α = .77) and Contingent Punishment Behav- iors (five items, α = .84). Respondents were asked to evaluate statements on a Likert scale from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree. The content validity of all items was assessed in terms of underlying factors and whether they represented reflective or formative indicators (MacKenzie, Podsakoff, & Jarvis, 2005). The examined item groupings were found to be reflective indicators and were tested using one-factor congeneric measure- ment models. The results supported the original factor structure for both instruments (see Podsakoff et al., 1984, 1990). Social Desirability Biases. A shortened-version (10 items) of the Social Desirability Scale (Crowne & Marlowe, 1960) was included in the questionnaire under the title: “View of yourself ”. Barlow, Jordan, and Hendrix (2003) used the same 10-item scale (α = .92) in a study of US cadets (N = 794). In the current study, respondents were asked to rate each statement on a Likert scale where 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. All items were evaluated for their contribution to the particular latent variable by assessing standardised regression weights, critical ratios, and factor scores (see Gray & Densten, 2007). Statistical analyses indicated that two items had non-significant critical ratios and were omitted from further calculations resulting in two reflective factors, namely Self-Deception: four items, α = .89 (e.g. no matter whom I’m talking to, I’m always a good listener); and Impression Management: four items reverse-scored, α = .75 (e.g. I sometimes try to get even rather than forgive and forget). While three items are considered statistically adequate for a just identified model, four items loading on a latent variable is sufficient to demonstrate convergent validity (Chin, 1998). Common Method Variance. Additional items were included among the leadership items to provide a marker variable to assess common method variance. The recommendations of Lindell and Whitney (2001) were followed which involved the creation of a highly reliable factor which operated at the organisational rather than at the individual level but was not theoretically distinct or statistically independent from the items in the main instruments. Items from the Organizational Citizenship Behaviors Scale (Podsakoff et al., 1990) were selected: Three items from the civic virtue and one from the conscientiousness sub-scales (α = .74). The resulting factor provided a robust measure of common method variance. Innovation. An innovation scale was included to enable the transformational and transactional leadership factors to be considered as formative rather than reflective constructs within the structural equation models (see Densten, Gray, & Sarros, 2006). Four items from the Organizational Culture Profile (Sarros, Gray, Densten, & Cooper, 2005) that represented Innovation (α = .80) were selected (e.g. to what extent is your organisation recognised for: being innovative, or quick to take advantage of opportunities). Respondents were asked to evaluate statements on a Likert scale from 1 = not at all to 5 = very much. Analyses The study used a multiple-method factor approach (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Podsakoff, & Lee, 2003) to assess the impact of social desirability biases on transformational and transactional leadership behaviors which also took into account common method variance. This approach developed from Schaubroeck, Ganster, and Fox’s (1992) research which presented a con- founded measurement model that assessed the measurement contamination within a latent-variable model. Several studies have since provided empirical support for this model (Brown & Keeping, 2005; Williams & Anderson, 1994) which involves allowing each substantive indicator to have additional factor loadings, attributable to the substantive factor and a bias factor (e.g. common methods variance). The technique involves multiple first-order bias factors being added to the model that load directly onto the items of the factors under investigation to provide a more precise assessment in terms of the items and their biases. According to Williams, Edwards, and Vandenberg (2003), this type of technique yields more evidence about the extent of bias than traditional approaches using partial correlation and multiple regression. While the one-factor congeneric measurement model procedure is useful in determining construct validity of a single factor, higher-order confirma- tory factor analyses (HCFA) were used to assess the unique variance of each factor and to evaluate the overall model fit (McDonald, 1999). This proce- dure allows common method variance and other biases (i.e. social desirabil- ity biases) to be statistically investigated (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, 2003). MacKenzie et al. (2005) suggested that the leadership constructs should be organised into reflective and formative indicators. In practical terms, this means that the eight substantive first-order factors (e.g. Articulates Vision, Fosters Acceptance of Goals) were considered reflective while the two substantive second-order factors of transformational and transactional leadership were considered formative. Three additional reflective factors were included in the HCFA, namely Common Method Variance and the two social desirability factors of Impression Management and Self-Deception which were loaded directly on the item-level responses (see Podsakoff et al., 2003). Finally, a reflective outcome factor of Innova- tion from the Organizational Culture Profile (Sarros et al., 2005) was also included as recommended by MacKenzie et al. (2005) for models containing formative factors. An acceptable model (Model B, see Figure 1) was achieved, 2 =1573.77, df = 774, p = .000; CFI = .91; TLI = .89; RMSEA = .04; SRMR = .04 (for further details see Densten et al., 2006). RESULTS Table 1 presents the means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations among the leadership, common method variance, and social desirability factors. The relationships among the leadership factors were consistent with previous research (Podsakoff et al., 1984, 1990). Table 2 presents the two models, namely Model A: Baseline Model which shows the standardised loadings for each item on its respective factor without taking into consideration common method variance or social desirability 2 biases. This resulted in an inadequate fit ( = 2315.50, df = 832, p = .000; CFI = .82; TLI = .81; RMSEA = .06; SRMR = .14). Item 1 was the only item which had a non-significant estimation and therefore, this item was excluded from further analysis. Model B had a superior fit to Model A as a result of taking into account common method variance and the social desirability factors of Impression Management and Self-Deception. Common method variance had significant positive loadings on all except two leadership items (items 31 and 35). Common method variance was calculated to account for systematic sources of error (Cote & Buckley, 1987) which then allowed the unique impact of Self-Deception and Impression Management on each leadership factor to be examined. Overall, Self-Deception and Impression Management had differential effects on various leadership factors. Both Self-Deception and Impression Management had significant positive loadings for all items on Provides Individual Support and Provides an Appropriate Model. Self-Deception had significant positive loadings for all items on Fostering Acceptance of Goals, Intellectual Stimulation, and Contingent Reward Behaviors. There were significant negative loadings on two items for Contingent Punishment Behaviors (items 19 and 36). Impression Management had significant positive loadings on one item for Articulates Vision (item 34), two items for Fosters Acceptance of Goals (items 23 and 30), and three items for Contingent Reward Behaviors (items 8, 18, and 35). Impression Management had significant negative loadings for all items on High Performance Expectations and Contingent Punishment Behaviors. DISCUSSION This study examined the extent to which self-perceptions of leadership behaviors are distorted by self-deception and impression management in order to gauge the degree to which leaders hold and transmit romantic notions about their leadership. The unique relationships among the social desirability factors and the leadership factors were investigated after common method variance had been taken into account. A key contribution of the study is the identification of the variations in the impact of 570 © GRAY 2376) AND = © 2007 Inte rna tio nal SD 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1. Articulates Vision 4.64 .71 2. Fosters Acceptance of Goals 5.35 .59 .54*** 3. Intellectual Stimulation 5.81 .71 .54*** .51*** 4. Provides Individual Support 5.76 .73 .38*** .50*** .40*** 5. High Performance Expectations 5.59 .85 .46*** .48*** .39*** .60*** 6. Provides an Appropriate Model 6.03 .75 .47*** .80*** .46*** .49*** .43*** 7. Contingent Reward Behaviors 5.85 .68 .35*** .58*** .46*** .50*** .38*** .50*** 8. Contingent Punishment Behaviors 4.79 1.02 .18*** .15*** .16*** .19*** .46*** .16*** .18*** 9. Self-Deception 3.73 .75 .12*** .21** .09*** .19** − .03 .19*** .09* − .10* 10. Impression Management 3.86 .53 .15*** .26*** .22*** .27*** .09* .21*** .29*** − .03 11. Common Method Variance 5.55 .91 .26*** .28*** .22** .28*** .33*** .35** .20*** of Asso ciation Impression Management): 1 = * 8 p < .05 level (two-tailed); ** strongly disagree to 5 = p < .01; *** p < .001. strongly agree. 9 10 .17*** .14** .08 .17*** DENS TEN among Variables (N Note: Leadership Behavior and Common Method Variance: 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree; Social Desirability Biases (Self-Deception and Applied .Ps ycholo gy 20 07 The .A uth ors M Factors com pila tion Jour na l TABLE 1 Means, Standard Deviations, and Intercorrelations TABLE 2 Estimates, Common Method Variance, Impression Management, and Selfdeception Loadings on Leadership Factors (N = 594) Model A Item Factor Q11 Q21 Q29 Articulates Vision Q34 Articulates Vision Q03 Fosters Acceptance of Goals Q13 Fosters Acceptance of Goals Q23 Fosters Acceptance of Goals Q30 Q07 Q17 Q26 Model B SD IM .43*** .09 .05 .46*** .51*** .50*** .47*** .51*** .53*** .40*** −.08 Est. Est. Articulates Vision .65*** .47*** Articulates Vision Fosters Acceptance of Goals .64*** .80*** .69*** .70*** .70*** .76*** .66*** .47*** .63*** .43*** .17*** .21*** .45*** .32*** Intellectual Stimulation Intellectual Stimulation Intellectual Stimulation .21*** .28*** .51*** .46*** .57*** .69*** .34*** .37*** .41*** .16** .17** .23*** −.05 Q32 Q16 Q25 Q31 Q04 Intellectual Stimulation Provides Individual Support Provides Individual Support Provides Individual Support .46*** .80*** .87*** .51*** .54*** .58*** .42*** .34*** .37*** −.09 Q14 High Performance Expectations .33*** .47*** .61*** .20*** .20*** .33*** −.03 .60*** .63*** .15* .33*** .39*** .20*** .04 .09 Q24 High Performance Expectations Provides an Appropriate Model Q12 Provides an Appropriate Model Q22 Provides an Appropriate Model Q08 Q18 Q27 Q33 Q35 Contingent Contingent Contingent Contingent Contingent .90*** .50*** .60*** .81*** .64*** .76*** .81*** .80*** .35*** .87*** .31*** .30*** .84*** .40*** .59*** .55*** .56*** .23*** .47*** .39*** .52*** .51*** .28*** .39*** .45*** .43*** .07 −.03 Q2 Q09 Q19 Q28 Contingent Punishment Behaviors .69*** .82*** .83*** .53*** .67*** .66*** .35*** .39*** .46*** −.03 −.14* .02 Q36 Q37 Contingent Punishment Behaviors .48*** .58*** .39*** .46*** .19*** .29*** −.20** −.29*** −.27*** −.22*** −.20*** −.01 −.16*** High Performance Expectations Reward Reward Reward Reward Reward Behaviors Behaviors Behaviors Behaviors Behaviors Contingent Punishment Behaviors Contingent Punishment Behaviors Contingent punishment Behaviors Note: Est. = Estimate, CMV Impression Management. * p < .05 level; ** p = Common Method Variance, SD < .01; *** p CMV .08 .05 .19** .09 .06 .16** .15** .11 .10 .39*** .47*** .27*** .38*** .02 .05 .34* .31*** .22* −.17*** −.22** −.11** .12* .35*** .16** .40*** .29** .37*** .36*** .29*** = Self-Deception, IM .12* .16*** .12* .10** .10*** .08 .10 .18*** = < .001. Self-Deception and Impression Management across leadership factors. These variations suggest that different processes underpin how leaders attempt to convince themselves and others of their leadership abilities. Although it is logical to expect that Self-Deception and Impression Management would inflate all transformational leadership factors because these behaviors contribute to promoting socially desirable self-images, surprisingly, the results indicate that Self-Deception had no impact on the transformational leadership factors of Articulates Vision and High Performance Expectations. Both Self-Deception and Impression Management had a positive impact and thereby inflated the responses for items loading on the two transforma- tional leadership factors of Provides Individual Support and Provides an Appropriate Model. The inflated scores in relation to Self-Deception suggest that leaders bolster their self-perceptions in regard to these aspects of leadership which contribute to a favorable self-image. The positive impact of Impression Management on Provides Individual Support and Provides an Appropriate Model reflects the promotion of socially desirable images of an effective leader in terms of: Showing respect for others, being thoughtful and considerate, as well as leading by example and providing a good model. These behaviors are likely to contribute to projecting an image of a trustworthy and competent leader (Chemers, 2002). The results are consistent with the findings of a study by Gardner and Cleavenger (1998) who con- cluded that the use of the impression management strategy, exemplification, was related to presenting an image as a worthy role model and was positively related to leader effectiveness. Also, Rozell and Gundersen (2003, p. 212) suggested that exemplification is related to “perceptions that a leader is transformational, effective, and capable of creating follower satisfaction”. A similar relationship is evident in regard to Contingent Reward Behaviors. SelfDeception inflated scores on items such as provide rewards and recognition. Therefore, leaders appear to deceive themselves concerning the extent to which they provide rewards and recognition. Giving rewards plays a central role in the social exchange process between leaders and followers ( Hollander, 1978), so it is feasible that leaders would perceive themselves as providing rewards that are likely to be valued by followers. Thus, such behaviors contribute to positive leader self-identity. The significant positive impact of Impression Management on two items for Contingent Reward Behaviors: Giving positive feedback and providing recognition is consistent with leaders using ingratiation strategies to appear more likable in the eyes of followers (Gardner & Cleavenger, 1998). Further, leaders are likely to assume in terms of their implicit theories concerning follower expectations of leaders that these behaviors would be considered socially desirable by followers and would encourage follower support. In terms of Fostering Acceptance of Goals, the results suggest that leaders deceive themselves in regard to the extent to which they encourage team work and collaboration among followers. In addition, leaders appear to project an image that they facilitate team attitudes and spirit to achieve group goals. According to van Knippenberg and Hogg (2003), promoting group or team salience increases the status of members and such behaviors are likely to be well received by followers. Consequently, leaders are likely to promote these behaviors as part of creating a favorable image and making a good impres- sion on followers. Self-Deception inflated the scores on all items loading on Intellectual Stimulation (e.g. challenge others to think about old problems in new ways, ask questions that prompt others to think) which suggests that leaders appear deceive themselves about the extent to which they challenge followers to think in new ways. Intellectual stimulation is a very desirable leadership behavior because leaders view themselves as the main drivers of innovation and change. Therefore, leaders may be protecting their self-image by deceiving themselves about the extent to which they encourage others to to rethink the way they do things. Interestingly, there was no relationship between Impression Management and Intellectual Stimulation. These results suggest that while leaders may be aware of the importance of intellectual stimulation for encouraging innovation, they realise intuitively that there is little social benefit for them personally from encouraging followers to challenge the status quo. This conclusion is consistent with Rosenberg’s (1979) theory that individuals are only motivated to use impression management where it improves social relations, enhances self-esteem, or contributes to desired identities. In addition, actually encouraging others to be innovative involves risk and frightens leaders (Ahmed, 1998) which could also account for why there was no relationship between Impression Management and Intellectual Stimulation. The negative impact of Self-Deception on two items of Contingent Punishment Behaviors suggests that leaders engage in self-denial concerning their use of these behaviors as part of their repertoire, namely to show displeasure when employees’ work is below acceptable standards and to reprimand employees if their work is below standard. In other words, these behaviors make little positive contribution to favorable self-presentation by leaders. Further, the negative impact of Impression Management on all items for Contingent Punishment Behaviors suggests that leaders appear to downplay their use of these behaviors because it is unlikely that if leaders demonstrate their disapproval and reprimand followers that such behaviors would attract follower approval. The results appear to corroborate Gardner and Cleavenger’s (1998) conclusions that leader intimidation is associated with negative follower perceptions of leaders. The results are consistent with implicit leadership theory which identified that negative attributions of leaders by followers (e.g. tyranny) does not facilitate constructive leadership ( Epitropaki & Martin, 2004). Similarly, in our study, leaders appear to recognise the negative consequences of using contingent punishment on productive relationships with followers. Leaders did not engage in Self-Deception in relation to High Performance Expectations. However, the negative impact of Impression Management on High Performance Expectations (expect a lot from employees, insist on only the best performance, and will not settle for second best) suggests that leaders downplay their use of High Performance Expectations and recognise that expecting exceptional performance from followers may not ingratiate themselves to followers. The results might indicate that leaders appreciate that followers may have concerns regarding whether they are able to fulfill high leader expectations. While encouraging or exhorting followers to search for new and better ways of operating has been shown to increase performance in the long term, it decreases performance in the short term (MacKenzie, Podsakoff, & Rich, 2001). Consequently, in the short term, using high performance expectation behaviors could have negative social outcomes for leaders and may account for the under-reporting of these behaviors. There was no relationship between Self-Deception and Articulates Vision, which suggests that leaders do not distort their self-perceptions concerning the degree to which they share their visions. Apart from one item: Able to get others committed to my dream, there was no relationship between Impression Management and Articulates Vision. The results seem counter-intuitive but may relate to the particular sample of Australian executive leaders in the study. Articulates Vision had the lowest mean score of all the leadership factors, which suggests that respondents perceive that their engagement in all other leadership behaviors exceeds sharing a vision. These findings pro- vide an opportunity for further research. Practical and Theoretical Implications Overall, the results provide evidence that Self-Deception inflates most transformational leadership and Contingent Reward Behaviors and deflates Contingent Punishment Behaviors in leader self-attributions. In a practical sense, giving feedback to leaders in regard to their use of self- deception could provide opportunities for leaders to gain insight into the extent to which they use self-deception for self-enhancement purposes. In addition, it may draw attention to possible discrepancies between their “espoused theo- ries”, that is, how people talk about thoughts, feelings, and ideas and their “theories-in-use” which determine actual behavior (Argyris, 1999). Leaders should be encouraged to engage in self-monitoring which could enable them to develop greater self-awareness of their strengths and limitations. In terms of impression management, the results indicate that leaders tend to over-report most transformational leadership behaviors but downplay expectations of follower high performance as well as their use of contingent punishment. Again, providing feedback to leaders may assist them to understand the likely impact various impression management tactics may have on followers. Coaching could enable leaders to appreciate the impression management strategies that are most effective. These strategies may assist leaders to develop more accurate self-perceptions which are associated with enhanced individual and organisational outcomes ( Yammarino & Atwater, 1993). The findings suggest that leaders appear to distort the images they project to appear more favourably disposed to followers. The results have implica- tions in terms of leader–follower relational authenticity. According to Eagly (2005), unless relational authenticity can be established, leaders are unable to elicit the personal and social identification of followers required to achieve success. In addition, if followers hold romantic notions of leader- ship and expect too much of their leaders, there is a risk that followers may be disappointed in their leaders and become disillusioned. In other words, creating romantic images of leaders may hinder leader–follower relationships because followers may develop unrealistic and unfulfilled expectations. This can be seen as the downside of impression management. Transformational leadership is predicated on leaders having credibility and building trust with followers. Consequently, leaders need to be aware of the potential ramifications when they consciously or unconsciously attempt to influence follower perceptions. This study makes several valuable contributions to the romance of leadership theory. While most of the research on the romance of leadership has taken a follower-centric approach, a major contribution of this study using a leader-centric approach is to develop theory concerning the pro- cesses involved in the romance of leadership. The study demonstrates how selfdeception and impression management have unique relationships with various transformational and transactional leadership factors which suggests that different and complex processes are occurring as leaders attempt to convince themselves and others of their abilities to lead. Further, the findings challenge theories of authentic leadership (e.g. Bass & Steidlmeier, 1999; Gardner, Avolio, Luthans, May, & Walumbwa, 2005). Given the self-serving nature of self-deception ( Litz, 2003) and the demonstrated impact of impression management, it would seem to be a romantic notion to contemplate that leaders could ever behave in a totally authentic manner. The results provide empirical evidence of the distortions to self-attributions which underpin implicit theories of leadership. In other words, the results indicate that leaders hold overly positive self-images as a result of attributional “errors” which reflect romantic or idealised images of themselves as leaders. Given that it is well established in the impression management literature that leaders influence follower behaviors and leaders stand to gain from perpetuating romantic ideas concerning their leadership, we contend that leaders initiate the leader attribution process. Our research highlights the potential for leaders to play a more active role in influencing follower attributions of leaders than previously acknowledged in the follower-centric approach to the romance of leadership. Therefore, we propose that leaders “woo” followers by using impression management strategies to create a frame of reference for followers so that leaders appear “successful” in the eyes of followers. This proposition goes to the heart of leadership by clarifying the origins of the romance of leadership and raises a key question: To what extent should leaders engage in self-deception and impression management to optimise their influence in leader–follower relationships without creating unrealistic follower expectations that cannot be met? Limitations and Further Research A number of limitations need to be taken into account which suggest directions for future research. This study was based on a nation-wide survey of Australian business executives and therefore we recommend that the study should be replicated in other countries to investigate the impact of different cultures on self-deception and impression management. Although common method variance was taken into account, all the usual limitations associated with studies based on cross-sectional data apply. The study relies on self-report data gathered from leaders only, which may be seen as a limitation of the study. To address this concern and to validate the conclusions of the current study, we recommend that further research be conducted based on an investigation of the implicit leadership theories of leader–follower dyads. This research would allow the compari- son of follower perceptions of their leaders with leader self-attributions and may assist in clarifying the reciprocal relationships between leaders and followers that contribute to the development of leader attributions. Such an approach could provide additional insights into the romance of leadership process. In addition, this research could be extended to explore the motives of leaders to use self-deception and impression management to influence others by undertaking 360 degree research which would involve collecting data from superiors and peers in addition to followers (i.e. to investigate how leaders “woo” their bosses and colleagues). Longitudinal research could clarify how the romance of leadership develops over time in association with leader–follower relationships. Further research should investigate whether there are significant differences among respondents grouped according to gender, organisational level, and distance from leader. For example, followers who are closer to their leader may see through the impression management tactics used by their leader while those further away might have greater difficulty. Given that this study demonstrates the significant impact that self-deception and impression management have on leadership, we recommend that future studies of leadership behaviors using self-rated measures should control for the powerful effects of these two processes. Future research could also con- sider using other measures of impression management, for example, the Leader Impression Management Questionnaire (Gardner & Cleavenger, 1998), to provide further insights into the range of impression management tactics utilised and their corresponding effects. Qualitative research should be conducted to investigate leaders’ own prototypes of effective leadership which could be compared with follower prototypes of leadership to advance understanding of the similarities and differences in leader–follower perceptions of leadership. While Meindl (1995) suggested that follower construction of leadership leads to follower commitment to the leader, further investigation of the motives that underpin the construction of leadership images by leaders and followers is required.