- Openground

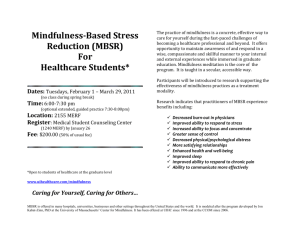

advertisement