INSIDE THE LIFE OF THE MIGRANTS NEXT DOOR

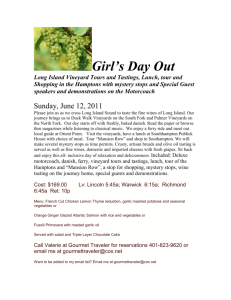

advertisement

INSIDE THE LIFE OF THE MIGRANTS NEXT DOOR Nathan Thornburgh. Time. New York: Feb 6, 2006.Vol.167, Iss. 6; pg. 34, 10 pgs Subjects: Migrant workers, Aliens, Social conditions & trends, Boundaries, Immigration policy, Towns, Territorial issues, Social impact Locations: Hamptons-Long Island NY, Mexico Author(s): Nathan Thornburgh Document types: Cover Story Section: SOCIETY Publication title: Time. New York: Feb 6, 2006. Vol. 167, Iss. 6; pg. 34, 10 pgs Source type: Periodical ISSN/ISBN: 0040781X ProQuest document ID: 985457391 Text Word Count 6155 Document URL: http://proquest.umi.com/pqdlink?did=985457391&sid=1&Fmt=3&clientId=9874&RQT=309&VN ame=PQD Full Text (6155 words) Copyright Time Incorporated Feb 6, 2006 [Headnote] Thirty years of migration-mostly illegal-connect a small town in Mexico to New York's wealthy Hamptons. How both sides have benefited, and paid a price ON A CRISP SATURDAY NIGHT IN EARLY winter, an armada of Hyundais and Saturns arrived at the colonnaded Bridgehampton Community House in the center of the Hamptons, a thin necklace of ultra-wealthy hamlets at the tip of New York's Long Island. The Hamptons are best known as a summer playground for Manhattan millionaires. But this night, the people who service the lavish Hamptons lifestyle were throwing their own party. They caravanned from a nearby church, little girls in frilly dresses and pomaded boys in squeaky shoes, shepherded by their parents-the roofers who tack gray slate to colonial homes, the maids who scrub toilets and dust Swarovski stemware, and the gardeners who feed the Hamptons' endless appetite for formal English gardens and straight hedgerows. The hundred or so guests had gathered for a quinceanera-a souped-up Latino version of a sweet-16 party, thrown for a girl's 15th birthday. But this was a coming-of-age celebration not just for the birthday girl but also for the Mexican community that has grown up in the Hamptons. Nearly all the attendees come from a town called Tuxpan in the green hills of the centralMexican state of Michoacán, which has seen several generations of young workers move to this far, affluent corner of the U.S. They came with nothing, and many have managed to build a solid facsimile of middle-class American life. Still, most of them are-in the hard parlance of the immigration debate-illegal aliens, part of an emerging presence that was once seen as a blessing but has turned into one of the Hamptons' biggest controversies. The same souring dynamic echoes in cities and towns from Tuscaloosa, Ala., to Tacoma, Wash., as migrants push into new communities with increasing numbers and confidence. Their ascension has caused a thousand brushfires of resentment throughout the country. A TIME poll conducted last week found that 63% of respondents consider illegal immigration a very serious or extremely serious problem in the U.S. Washington, having heard the call, is creaking into action. President George W. Bush has made it a New Year's resolution to pass a guest-worker program, coupled with robust policing of the border. Under his proposal, undocumented workers already in the U.S. would register here, work for as many as six more years and then return to their native country to reapply if they want to continue living in the U.S. Immigrant advocates oppose the idea, saying that a full amnesty giving permanent legal status is the only practical way to deal with the estimated 11 million illegal aliens in the U.S. without sending the economy, not to mention its poorest workers, into shock. But neither the President nor the amnesty crowd has a bill already rolling through Congress. That distinction belongs to House conservatives, who passed a hard-line border-security measure, stripped of any nod to guest-worker status, in December. The Senate will likely consider it this month. In the meantime, an estimated 700,000 undocumented immigrants from around the world continue to enter the U.S. each year, according to the Pew Hispanic Center. TIME followed the fortunes of those from Tuxpan-both in the U.S. and in Mexico-and found that American misgivings about illegal immigration are mirrored by the illegals. Again and again, the immigrants asked themselves the question: Is coming to the U.S. worth it? The wages are undeniably good, as much as $15 an hour for manual labor in the Hamptons, 10 times the rate for the same work in Tuxpan. But even among the relatively well-off guests at the quinceañera, there has been a heavy price to pay for the opportunity: estranged marriages, wayward children, hostile neighbors here in the U.S. and a beloved hometown in Mexico whose long-term prospects seem to dim with each worker lost to the north. * THE TRAILBLAZER THE STORY OF TUXPAN'S TRANSFORMATION from a provincial town of 30,000 into a major conduit of cheap labor for the Hamptons begins with a single wanderer. Mario Coria, 55, grew up so poor in Tuxpan that at age 11 he left for Mexico City to work in construction, a skinny kid carrying 80-lb. bags of cement and mortar on ramshackle scaffolding, sending nearly all his earnings back to Tuxpan. In January 1977, when he was 26, Coria had a chance encounter that would change his life-and that of Tuxpan-forever. He ran into a vacationing restaurateur from Bridgehampton who was asking directions to the Palace of Fine Arts in downtown Mexico City. Coria showed him the way, the men struck up a halting conversation in Spanish, and within two years, Coria had accepted the American's invitation to work as a gardener in the Hamptons. A tourist visa to the U.S. came included with his plane ticket, both easily arranged by a Mexico City travel agency. The Hamptons, like much of the U.S., had a very different relationship to illegal immigrants 30 years ago. Back then, Coria was one of only a handful of Spanish-speaking immigrants who lived in the area. His blend of industry, attention to detail and, eventually, confidence in his vision as a landscaper made him a hit with the wealthy Hamptonites. One family liked him so much that they had their personal attorney help him apply for legal residency. But even after he was legal, he still found it tricky being gardener to the rich and famous. He is fond of recalling how he walked out on the actress Lauren Bacall after, he says, she yelled at him for cutting a clutch of lilies too short. Overall, however, his perseverance has been richly rewarded. Coria started out making just $3.25 an hour, but today he is a U.S. citizen and owns a house in the Hamptons town of Wainscott. He bought it for $125,000 in 1996, but similar homes are selling for more than half a million dollars today. A trip to Ororicua, the shantytown in the mountains outside Tuxpan where his grandmother was born, highlights just how far Coria has come. His grandmother's people still live in sloping clapboard shacks with dirt floors. Coria's home in Tuxpan is a porticoed five-bedroom residence in the center of town, and he drives a late-model Nissan Pathfinder. In the front of his vast garden are orchids and lilies he brought from the Hamptons. In the back are groves of guava, orange and avocado. But Coria's pursuit of success has taken a heavy toll. Being just about the only Mexican gardener in the Hamptons when he first arrived meant less competition, but it also made him more homesick. He returned to Tuxpan in the winters, but "every March when I went back to America, there would be two weeks when I just didn't want to get out of bed "he says. In 2005 the depression came and didn't leave. The more financially secure he was, Coria says, the more overwhelmed he became by memories of his bitter past: the beatings he suffered as a boy working construction in Mexico City; the disapproval of his mother, who never seemed satisfied with the money he sent back every week. Coria fled the Hamptons abruptly last year in the middle of the busy summer season to recuperate in Tuxpan. Once a week, he makes the six-hour round-trip drive to see a therapist in Mexico City. He's planning on returning to the Hamptons in March to begin buying seeds and drawing up plans for his clients' summer 2006 gardens. But even if he goes back, he says, he doesn't think he can spend more than two additional seasons in the Hamptons. "Walking the streets of Tuxpan, I know who I am," he says. "Over there, even after all these years, I am just a stranger." * THE NEWCOMERS THE DARKER COMPLEXITIES OF BUILDING A life abroad are lost on most Tuxpeños, who see Coria's mansion in Mexico and his new truck as tangible evidence of his success. Early on, friends and relatives asked how they could make their way to the Hamptons. In 1985 he brought over his half brother Fernando. Fernando invited two friends, who started bringing their relatives. A handful became dozens. Dozens become hundreds. There are no reliable estimates, but workers in the Hamptons say there are as many as 500 Tuxpeños living full-time in the area, and scores more show up during the workfilled summer months. Many of the new arrivals cross by foot near Douglas, Ariz., and then get rides to big cities where they catch vans, buses or even airplanes to New York. ( Southwest Airlines is a popular choice for its fares, as low as $99 oneway.) The lucky ones with tourist visas can fly directly from Mexico City to New York City's J.F.K. Airport. But whether they travel by land or by air, relatively few get caught or even delayed. Their safety comes in numbers: hundreds of thousands of migrants will always win a game of Red Rover with a little more than 11,000 border-patrol agents. Of course, people are not just coming from Tuxpan. Workers have been flooding into the Hamptons from other parts of Mexico, from Colombia, Costa Rica, Guatemala and Honduras. And the Hamptons, like so many suburban areas facing the same deluge, are feeling the strain. The community's complaints against the newcomers are varied and vigorous. Neighbors rail against single-family homes that are carved into hostels housing a dozen or more men at a time. Uninsured drivers, some of whom display the daredevil driving style of rural Latin America, anger local motorists. Day laborers looking for work clog parking lots, and they are more than just an inconvenience. Flooding the market with cheap labor, they're driving down wages for everyone. Even some of the more established undocumented workers are critical of the newcomers. "A hard worker used to be able to make $15 an hour here," says Gabriel, 33, a Tuxpan native who owns a small gardening business and who, like many of the people interviewed for this story, asked not to be identified by surname. "But there are too many workers here now. They're working for $10 an hour." A crowd of Ecuadorian day laborers gathered at the East Hampton train station in the fall were asking $12 an hour. The employers who stopped by ranged from heating repairmen to housemoms. Homeowners and renters make up almost half of those who hire day laborers, according to a recently published UCLA study. The day laborers, who exist on the bottom of the undocumented-worker food chain, say they feel slightly shut out by those immigrants who already have a foothold in the Hamptons. "Their attitude is, we were here first" says a worker named Oscar. "But we deserve the same chance they had." The old-timers, for their part, complain about the newcomers' work ethic. "The people who come these days just see the nice cars or the money on the streets of Tuxpan," says Coria. "They don't know how much hard work it takes to make it in the Hamptons. So many of them come, get disillusioned very quickly and return to Mexico empty handed." Octavio, 19, a shy mechanic from a poor settlement outside Tuxpan, knows how hard it can be, and he is trying to hold on. In March he paid $2,200 to a door-to-door smuggling service that picked him up in Tuxpan and dropped him off in the Hamptons. But it was no luxury ride. The trip took eight days, including three days and nights of nonstop driving from Douglas, Ariz., where he walked across the border, to the Hamptons. The Chevy Astro van that took him through the U.S. was crammed with 13 people-11 other Tuxpeño passengers and two alternating drivers. "I wasn't ever scared" Octavio says about the journey. "Just very tired." After he arrived, it took only a few weeks for his English-speaking uncle to find him a job in an auto-repair shop and a room to rent. Octavio now lives in a single-family home that got the illegal immigrant makeover: slap a lock on every bedroom and try to squeeze in as many families and workers as possible. He pays $500 a month to share his home with eight other workers he doesn't know and barely trusts. But Octavio knows he's one of the lucky ones. His spot at the garage spares him the insecurity of hustling for temporary jobs as a day worker. The UCLA study reported that even when laborers find work, 49% say they have been cheated out of at least some of their pay in the past two months. Octavio recently got a raise to $10 an hour and supplements his income by doing freelance car repairs after hours, but after paying his rent and sending more than $1,000 a month to his mother (who plans to build a bathroom with running water), he doesn't have much money left. His only furniture is a mattress and a milk crate. Cardboard does the job of window shades. Octavio speaks just a few words of English and says he lives in fear of his Anglo neighbors, who seem to be constantly scolding him on the street. He thinks they might be mistaking him for one of his housemates, who disrupted the quiet neighborhood with repeated attempts to do bodyrepair work on old cars in the driveway. * UNEASY NEIGHBORS THE HAMPTONS HAVE LONG CULTIVATED A climate of easygoing tolerance, and for years town leaders dealt with illegal immigration by simply looking the other way. But that too is changing, as the numbers grow larger and the complaints grow louder. Last November, in a crackdown that has been lauded by anti-immigration groups around the country, police began taking down information about the vehicles that came to the East Hampton railroad station to pick up day laborers. They traced the plates and sent letters to the IRS and federal Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency, saying that the cars' owners might be hiring illegal contractors and should be investigated. "Sure, it's unlikely that the feds would take action," says East Hampton village police chief Gerard Larsen Jr., "but put it this way: Would you want a letter from your local police department to the IRS saying that you're probably paying people off the books?" Larsen sees the crackdown as a way of targeting the problem without going after the workers directly-an acceptable solution for the sensitive political ecosystem of the Hamptons. Suffolk County Executive Steve Levy, who mainly oversees the more working-class communities west of the Hamptons, takes a more direct approach. Levy, a Democrat, has initiated sting operations on local contractors and helped towns bust lawbreaking landlords. His police also forcibly removed day laborers from a Farmingville 7-Eleven parking lot. Levy says the voters in his county appreciate his strong arm. "There's a tremendous disconnect between the public and these do-nothing politicians," he says. "You're seeing the beginnings of a citizens' uprising." The tensions are most evident in the complex relationship between the Hispanic immigrants and the German, Italian and Irish families that for a century formed the area's working-class backbone. Those locals were the ones who did the gardening, cleaning and cooking in the Hamptons before Latinos started showing up and working longer for less. And it's the working-class residents, not the wealthy summer-estate owners, who end up not only competing for work with but also living next door to the newcomers. "We have up to 60 single men being stuffed into homes of up to 900 sq. ft. That's not an exaggeration. Single-family neighborhoods have been turned upside down," says Levy. "It's very politically incorrect to say, but that's not what those homeowners signed up for in suburbia." Despite their grievances, however, many of those same working-class families have become addicted to the cheap labor. As a landscaper, Jeremy Samuelson has seen starting hourly wages for gardeners fall from $14 to $12 in the past decade, but he admits that he and his neighbors view cheap labor as a perk of living in the Hamptons. "People are making less, maybe, but now lots of people have house cleaners come once a week," he says. "And if you want your roof redone, you can just go to the corner, round up 20 guys, and they'll have it done in an afternoon for less than $3,000." * RESTLESS EXILES AS CROSSING THE BORDER HAS BECOME more difficult and expensive, workers are staying longer and bringing their children to live with them in the U.S. Julio, 18, and Carlos, 15, moved to the Hamptons from Tuxpan almost a decade ago with their parents Julio Sr. and Yadira. The boys grew up on PlayStations, sledding in the winter and pool parties in the summer. They speak accentless English and for most of their childhood were average happy-go-lucky small-town kids. But because the brothers were born in Mexico, they have no legal American papers, no Social Security numbers. And that means they are not able to apply for federal college loans or even prove that they meet the residency requirements of the local community college. Their parents have seen enough to know that without a college degree the boys would get no further than their parents had. So just before Julio was about to enter the 10th grade, the decision was made for the boys to go back to Tuxpan with their mother to finish high school there, which would make them eligible to attend a Mexican university. Their father would keep working in New York alone. Finding their place in Tuxpan has been hard for the brothers. In America they were too Mexican. In Mexico they are too American. Julio, for example, started out wearing the baggy clothes he bought at Banana Republic and the Gap before he left the Hamptons, but he quickly found out that what passes for universal teenage fashion in the U.S. is viewed as the indelible mark of a hoodlum in Tuxpan. Even his friends greet him with "What's up, gringo?" So Julio and Carlos spend a lot of time hanging out with other kids who, like them, are Americans in exile. There's Flor, 15, a cousin who also grew up in the Hamptons and speaks a rapid teenage patois. There's her boyfriend Luis, also 15, a basketball-crazy redhead who grew up outside L.A. "People get mad at us when we speak English together" says Julio. "They think we're trying to act all big. But it's just how we are." As part of their return plan, Julio and Carlos' parents have built their dream house just outside Tuxpan. It is a grand two-story affair with granite counters in the kitchen and views of the mountains from the boys' bedrooms. But cash is tight. In the U.S., Yadira had moved up from cleaning houses to working as a manicurist for an upscale spa in Bridgehampton. With tips from her wealthy clients, she made up to $200 a day. But returning to Tuxpan, she quickly found out that sustainable income is hard to come by in small-town Mexico. Yadira tried running a small convenience store-selling sodas, lollipops, toilet paperfrom the ground floor of her house. Those abarrotes can be found, it seems, in every other house in Tuxpan, and nobody appears to sell much of anything. After nine months, Yadira shut hers down. She now operates a clothing store. It is doing better than the convenience store, although on a typical afternoon, a few teenage girls stop in after school but don't have any money to buy anything. An elderly woman comes by to call a relative in Mexico City from one of the row of telephones in back. Yadira collects 20¢ for the call. To supplement her income, Yadira does manicures and facials when she can. She has also started to think about returning to New York, not solely for the money but because, like her sons, she has in many ways simply outgrown the town where cockfighting is the major pastime. "I thought it would be different coming back," she says with a sigh. "It can be so boring in this town." * AN ENDLESS CYCLE A QUICK GLANCE AT THE ECONOMY OF A SMALL Mexican town like Tuxpan makes it clear why undocumented workers continue to head north. Tuxpan's heyday was in the 1950s and '60s, when it gained fame throughout Mexico for its gladiolus. But overproduction slowly poisoned the soil, leaving Tuxpan in a slow decline. In the past decade, flowers have made a comeback, but the salary for working in the greenhouses or out in the field still averages only $10 a day. At the same time, the cost of living is comparatively high in Tuxpan. As in much of small-town Mexico, the large influx of cash from the U.S. has thrown the economy out of balance. According to Pew Hispanic Center estimates, almost half the 10.6 million adult Mexican immigrants living in the U.S. sent at least some money back to their relatives last year, for a 2005 total of $20 billion. In Tuxpan, as in many other towns in Mexico, the money is rarely used for bettering the community. Instead, there seem to be two impulses competing for those hard-earned dollars: a deep love of one's own family and a desire to show up everyone else's. Everyone buys Mom a house. Everyone buys a truck. Many buy subwoofers and chrome packages for their truck. When the returning workers descend on Tuxpan for the holidays in December, the local Yamaha motorcycle dealer has a field day. Rents in Tuxpan now average around $250 a month; completed houses can cost well over $100,000. Nike shoes cost up to $200 a pair. Seafood restaurants in town charge $10 a plate. "In America, we could go to restaurants whenever we wanted to," says the teenager Carlos. "Here, we can't afford it anymore." And the cycle of migration is selfpropelling. Bartender Alfonso Mayo López, 43, lost his job in the fall when the last bar in Tuxpan closed because all its customers had gone up north. López now sees fewer and fewer reasons not to leave his daughter and wife and join his brother in the Hamptons. "The more difficult it gets here" he says, "the more I think about going there." Roberto Suro, director of the Pew Hispanic Center in Washington, says the great irony of Mexican migration is that it often feeds the same problems that sent people north in the first place. "Many towns have lost the best of their labor force. There's money coming in [from the U.S.] but no job creation back home," he says. "It just shows that migration does not solve migration." The governments of the U.S. and Mexico are trying to encourage people to put the remittances to better use. In 2004 the U.S. Agency for International Development began a five-year, $10 million program to help Mexican microlenders boost small businesses. And the Mexican government is proud of its 3x1 initiative, a project that aims to unite the federal, state and local governments in Mexico with immigrants in the U.S. to fund programs for improving life in Mexico. But Tuxpan's Mayor Gilberto Coria Gudiño (no relation to Mario) says he doesn't know of any 3x1 projects in the region. When asked if he has a plan for ensuring that the next generation of Tuxpeños won't be lost to the U.S., he says his administration has paid $20,000 for a gigantic Mexican flag to be placed on the highest peak above Tuxpan. "This will send a message to all those who are working up north that they should be proud to be Mexican, not ashamed," he says. "It will tell them that Tuxpan welcomes them home with open arms!" There are some signs of change, but they're planted in rocky soil. Like Mario Coria, a Tuxpeño named Pancho found wealthy patrons who valued his hard work in the Hamptons. He worked as a gardener at one family's East Hampton estate for more than a decade while his wife Ruth worked as their housekeeper. When the matriarch of the family died, she left Pancho, his wife and three daughters a fair sum of money. Pancho won't say exactly how much, but it was enough to seed his American Dream for Tuxpan: state-of-the-art greenhouses for growing roses, orchids and gladiolus to be sold around Mexico. He hoped to supplement his inheritance with low-interest loans that the state of Michoacán earmarked for returning emigrants. He says the loans would allow him to employ up to 40 people. "When this greenhouse gets going," says Pancho, "I hope to be able to save many people from having to go to the Hamptons, myself included." Right now, however, the several plots of land he bought in the hills outside Tuxpan lie fallow. Applying for the loans proved more complicated than Pancho anticipated, and he has no backup plan. He ended up spending much of a recent visit to Tuxpan driving his beat-up Dodge Caravan around town, drinking with old friends, trying to figure out how to raise more money. * THE PRICE OF PROGRESS DESPITE THE FLOOD OF AMERICAN MONEY streaming into towns like Tuxpan, there is a palpable lack of vitality on the streets. In the summer working season, Tuxpan feels as if there's some great war on: all the fighting-age men have gone to battle the hedgerows up north. Only women, children and the elderly remain. That emptiness is felt acutely by Lucila, 75, mother of 13, eight of whom live in the U.S. She proudly gives a tour of her renovated house on one of the town's main streets. The back of the building is neat and thoroughly modern, with tile floors in the living room, modern appliances in the kitchen. Still standing in the front part are the three tiny adobe-walled rooms that used to be the entire house. Lucila and her husband slept in one room. The five girls slept in another. The eight boys slept in the third. Out back, just past where the refrigerator now stands, was a large pen that held up to 70 pigs. Besides tending the pigs, Lucila's husband grew corn and beans and did odd jobs as a tailor. Lucila taught knitting classes at her house to help the family scrape by. Nowadays Lucila doesn't have to worry about money-her children paid for the renovations in cash, a 50th wedding anniversary present in 1995 for her and her late husband-but she is lonely. Four of her daughters live in the U.S. permanently; three are citizens by marriage. Five sons work in the Hamptons; the other three are scattered across Mexico. Visits outside of Christmas are rare. Lucila occasionally talks on the phone with her children, but she spends most of her time walking through the enclosed town market and waiting for visits from the local priest. She keeps a bowl of salsa on the table at all times, just in case he stops by unexpectedly. "The padre loves spicy things," she says. But most days, not even the padre shows up. "There are times when I really miss my children," she says. The northern migration has taken its toll on nuclear family life in towns like Tuxpan. Countless men have girlfriends in the north, while their wives and children remain in the south. And the women left behind in Mexico are faced with the same temptations. Workers in the U.S. regard this threat with black humor. The idea that there's a guy who's back home in Mexico drinking your beer, sleeping with your wife and spending your hardearned money looms large in their mythology. He has even been given a name: Sancho. Taking a break from sodding a lawn in the Hampton town of Springs, a worker named Neftalí jokes that he has to wire some money to Mexico that weekend because, he says with a grin, "Sancho needs new shoes." The relentless separations put particular stress on children. When schoolteacher Claudia González's husband returned after a two-year stint as a farmworker in Texas, her young daughter chased her father out of the house, yelling, "You don't live here. Go back to Texas!" Says Gonzalez: "No amount of money from up north can bring those years back." * TIGHTENING BORDERS BEFORE THE U.S. BEGAN CRACKING DOWN on illegal immigration in the early 1990s, a push only accelerated by 9/11, many Tuxpeños flew back and forth easily on 10-year tourist visas. But as those visas expire, they're not being renewed under policies that seek to control more closely who gets into the U.S. The heightened border security has not, however, stopped undocumented Mexicans from getting in. The Pew Hispanic Center found that even though immigration is down since its peak in 2000, about 485,000 undocumented Mexicans were still crossing each year from 2000 to '04. In fact, the tougher restrictions have been a boon for the smugglers who sneak human traffic across the border. When Mario Coria's half-brother Fernando went to the U.S. in 1985, the trip from Tuxpan cost $200. Now the same trip costs more than $2,000. For Pancho, the rising profitability of human smuggling is proving too tempting. He used to work as an enganchador, or wrangler, in Tuxpan, earning $200 for each would-be migrant he steered toward his friends who worked as coyotes, smuggling people across the Arizona border. Now, with the business plan for his greenhouses in disarray, he says he plans to move to Phoenix, Ariz., and work as a facilitator for the coyotes, watching over the newcomers and arranging bus or plane tickets for them to their final destination. Pancho estimates he could clear close to $1,000 a week. Working as a facilitator isn't as dangerous as sneaking through the desert with a group of immigrants as the coyotes do, but under the tough new laws aimed at traffickers, Pancho could face felony time of up to 20 years if he's caught. It's a stunning risk for a family man to take, but Pancho just shrugs. "I think it will be fine," he says. "And besides, where am I going to get that kind of money in Tuxpan?" For those who are crossing, the traveling has become more arduous. The first time Gabriel, one of the guests at the Bridgehampton quinceañera, crossed the border in 1990, he left Tijuana at 6 p.m. and reached his sister in Los Angeles by 8 a.m. the next day. But after the border crackdowns of the mid-1990s, he has had to seek out new routes. In 1999 he flew from Mexico City to Montreal and went to a random downtown McDonald's, where he thought he could bump into Hispanics. If he found some Mexicans there, he reasoned, one of them would know how to sneak across the nearby U.S. border. Before long, he got a ride to a secluded place in the woods just north of the border, but an off-duty U.S. customs agent getting lunch at a Burger King drive-through spotted Gabriel as he walked out of the trees. He was fingerprinted, handed a summons to appear before a judge and released. The judge later issued Gabriel a voluntary departure order, giving him two months to arrange his affairs and move back to Mexico. For an already overburdened immigration system, voluntary departure keeps the U.S. from having to pay for jailing or deporting low-risk illegal immigrants like Gabriel. He did fly back to Tuxpan at his own expense but stayed only a couple months before illegally crossing once again, this time through Arizona, to rejoin his family up north. For anti-immigration advocates, the episode is typical of the leniency on both the northern and southern borders that is killing the system. Their outrage was directed at Mexico's National Human Rights Commission last week for its planscrapped a few days later-to distribute maps showing safe routes into the U.S. For Gabriel, however, the prospect of creeping and crawling through the woods just to reach his wife and two children in New York is humiliating. "I've got 15 years here," he says. "And crossing like that makes you feel like trash, like you're worth nothing." Rather than run the risk and expense of going home in the winter, many Tuxpeños, particularly the families, simply choose to stay year round, putting even more pressure on the educational, health and social-service agencies in the Hamptons. The East Hampton school system now has a population that is 25% Hispanic, including legal and illegal kids. At East Hampton High School, new students who don't speak a word of English drop in so frequently that the school has developed a twoweek crash course in basic phrases and American culture. There are signs of backlash from local taxpayers. A $90 million construction bond meant to alleviate overcrowding in East Hampton schools was rejected by voters last June, and some locals attribute the defeat to anger at the perceived costs of educating the kids of immigrant workers. BACK AT THE QUINCEAÑERA in Bridgehampton, the festivities continued, yet the price and the promises of immigration were never far out of mind. Julio Sr. was there, but his wife and sons were 2,000 miles away in Tuxpan. Pancho was still in Mexico, so his wife Ruth waltzed with their daughter Samantha, 3. Gabriel sat with his arm around his wife Jani and talked about how their daughter Lena, 8, born in the Hamptons, could petition to obtain permanent legal residency for her parents in 2015, when she turns 18. "But by then," he said, as if suddenly remembering, "I really hope we're living in Tuxpan."