Example 2 - Northern Arizona University

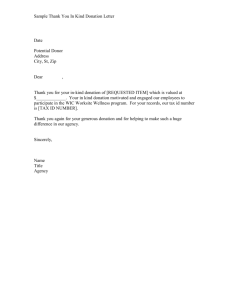

advertisement