2006 - ICES Gh.Zane

advertisement

ACADEMIA ROMÂNĂ

INSTITUTUL DE CERCETĂRI ECONOMICE “GHEORGHE ZANE”

ANUARUL

INSTITUTULUI DE CERCETĂRI ECONOMICE

“GHEORGHE ZANE” – IAŞI

(YEARBOOK OF THE “GHEORGHE ZANE”

INSTITUTE OF ECONOMIC RESEARCHES – JASSY)

TOMUL-15 ● 2006

(VOLUMES 15 ● 2006)

EDITURA ACADEMIEI ROMÂNE

2006

COMITETUL ŞTIINŢIFIC (SCIENTIFIC BOARD)

JAIME GIL ALUJA (Spania), AUREL BURCIU (România), EMILIAN

DOBRESCU redactor şef (România), OVIDIU GHERASIM (România),

MIHAI HAIVAS, (România), MARIO PAGLIACCI (Italia), MIHAI

PATRAŞ (Republica Moldova), TEODOR PĂDURARU secretar de

redacţie (România), ION TALABĂ (România), DORIAN VLĂDEANU

(România).

Adresa redacţiei

INSTITUTUL DE CERCETĂRI ECONOMICE “GH.ZANE”

Str. T.CODRESCU nr.2, cod 6600

Iaşi, tel. 02-32/ 315984

Pentru a vă asigura colecţia completă şi primirea la timp a revistelor,

apelaţi la serviciile de abonamente prin oficiile poştale şi factorii poştali.

Abonamente din străinătate se primesc la:

(Foreign subscriptions can be made through one of the following

companies):

EDITURA ACADEMIEI ROMÂNE, Calea 13 Septembrie nr.13,sector 5,

P.O. Box 5-42, Bucureşti , România, RO–050711,

Tel. 4021-411.90.08, 4021-410.32.00, Fax 4021-410.39.83

RODIPET S.A. Piaţa Presei Libere nr.1, sect.1, P.O. Box 33-57

Fax. 4021-222.64.07, Tel. 4021-618.51.03, 4021-222.41.26,

Bucureşti, România, Email: rodipet@ rodipet.ro.

ORION PRESS IMPEX 2000 S.R.L., Şos. Viilor nr. 101 Bl. 1, sc. 4, ap.

98, parter, P.O. Box 77-19, Bucureşti, sector 5,

Tel. 4021-301.87.86, fax. 4021-335.02.96

Adresa redacţiei

Adresa editurii

INSTITUTUL DE CERCETĂRI ECONOMICE

EDITURA ACADEMIEI ROMÂNE

“GHEORGHE ZANE”

Calea 13 Septembrie nr.13, sector 5,

Str. T.CODRESCU nr.2, cod 6600

P.O. Box 5-42, Bucureşti , România, RO–050711,

Iaşi, tel. 02-32/ 315984

Tel. 4021-411.90.08, 4021-410.32.00,

Fax. 4021-410.39.83

ACADEMIA ROMÂNĂ

FILIALA IAŞI

INSTITUTUL DE CERCETĂRI

ECONOMICE “GH. ZANE”

ANUARUL

INSTITUTULUI DE CERCETĂRI

ECONOMICE “GH. ZANE”

TOMUL nr. 15/2006

S U M A R

Mersul ideilor

ELISABETA JABA, CIPRIAN-IONEL TURTUREAN, Metodă

de analiză şi previziune a evoluţiei ponderilor

componentelor unui fenomen economic agregat. Aplicaţie

pentru exportul ţărilor UE-15 în perioada 1996-2005 …….

CORNELIU MUNTEANU, Studiu comparativ privind toleranţa

faţă de ambiguitate ………………………………………..

ALEXANDRU TRIFU, Informaţia factorul central al economiei

cunoaşterii sau al economiei informaţionale ? …………….

CĂTĂLINA LACHE, Gestiunea strategică a schimbărilor din

întreprinderile româneşti în perspectiva integrării europene

Probleme în actualitatate

MÁRTA STAUDER, Dezvoltarea rurală în Ungaria înainte şi

după aderarea la UE ……………………………………….

MARILENA MIRONIUC, Analiza şi managementul riscului

financiar în contextul mediului de afaceri din România …..

VIORICA CHIRILĂ, CIPRIAN CHIRILĂ, Analiza sincronizării

ciclurilor bursiere cu ciclurile economice: cazul României,

Franţei şi UE 15 ……………………………………..….…

ION TALABĂ, Aspecte specifice privind formarea, utilizarea şi

costul forţei de muncă în turism …………………………...

CIPRIAN-IONEL TURTUREAN, Structurarea informaţiei

economico-sociale la nivel microzonal – necesitate a

sistemului decizional al administraţiilor publice locale …...

An. Inst. cerc. ec. “Gh. Zane”, t. 15, Iaşi, 2006, p. 1–194

5

27

41

55

69

81

93

107

119

2

Puncte de vedere

ALEXANDER BOBRÓVNIKOV, Dinamica ondulatorie în

economia periferică

CORNELIU MUNTEANU, Strategia de marketing şi gestiunea

calităţii produselor universitare; studiu de caz …………….

VALERIU DORNESCU, Conversia datoriilor în acţiuni ca

metodă de asanare a economiei româneşti ………………...

IONEL-CIPRIAN ALECU, Asistarea deciziei la nivel regional

prin metoda pentagonului …………………………………

VALERIU DORNESCU, Corupţia “endemică” …………………

IONEL CIPRIAN ALECU, Consideraţii privind modelarea

incertitudinii economice utilizând intervale fuzzy

125

141

153

159

167

173

Contribuţii la dezvoltarea gândirii economice

TEODOR PĂDURARU, MIHAI HAIVAS, Alecsandru Puiu Tacu

– Creator de şcoală ...........................................................................

ALEXANDRU TRIFU, Centenar Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen

(1906-1994) ……………………………………………………….

183

185

Viaţa ştiinţifică ……………………………………………………... 191

An. Inst. cerc. ec. “Gh. Zane”, t. 15, Iaşi, 2006, p. 183–190

ROMANIAN ACADEMY

JASSY BRANCH

“GH. ZANE” INSTITUTE OF

ECONOMIC RESEARCHES

YEARBOOK

OF THE

“GH. ZANE” INSTITUTE OF

ECONOMIC RESEARCHES

VOLUME no. 15/2006.

CONTENTS

The progress of ideas

ELISABETA JABA, CIPRIAN-IONEL TURTUREAN, Method

for the analysis and forecast of the components’ evolution

in an aggregate economic phenomenon using their

weights. Application on the exports of EU-15 countries

from 1996 to 2005 ………..………………………….…….

CORNELIU MUNTEANU, Comparative Study on Managers’

Tolerance for Ambiguity …………………………………..

ALEXANDRU TRIFU, Information the core factor of the

Economics of Knowledge or of IT Economics ? ………...

CĂTĂLINA LACHE, Strategic management of the changes in

Romanian companies in view of the european integration

5

27

41

55

Present-day topics

MÁRTA STAUDER, Rural development in Hungary before and

after the EU-accession …………………………………….

MARILENA MIRONIUC, Analysis and management of the

financial risk within the romanian business framework …..

VIORICA CHIRILĂ, CIPRIAN CHIRILĂ, Statistical Analysis of

the Stock change Cycles and the Business Cycles: The

Case of Romania, France and UE 15 ……………………...

ION TALABĂ, Specific aspects of the training, use and cost of

labour in the travel industry ……………………………….

CIPRIAN-IONEL TURTUREAN, The structuring of socio–

economic information at micro-zone level – a necessity for

the public administration’s decisional system …………….

An. Inst. cerc. ec. “Gh. Zane”, t. 15, Iaşi, 2006, p. 1–194

69

81

93

107

119

Points of view

ALEXANDER BOBRÓVNIKOV, La dinámica ondularia en la

economía periférica ………………………………………..

CORNELIU MUNTEANU, Marketing Strategy and Quality

Management for Educational Programs; A Case Study …

VALERIU DORNESCU, The Debts’ conversion into shares as a

sanitation method for the Romanian economy ……………

IONEL-CIPRIAN ALECU, Assisting decision-making at regional

level using the pentagon method …………………………..

VALERIU DORNESCU, The “endemic” corruption ……………

IONEL CIPRIAN ALECU, Remarks on the modelling of

economic uncertainty by using fuzzy intervals ……………

125

141

153

159

167

173

Contributions to the development of economic thinking ………... 183

Scientific life …..………………………………………………….…. 191

ELISABETA JABA

CIPRIAN-IONEL TURTUREAN

The progress of ideas

METHOD FOR THE ANALYSIS AND FORECAST

OF THE COMPONENTS’ EVOLUTION IN AN

AGGREGATE ECONOMIC PHENOMENON USING

THEIR WEIGHTS. APPLICATION ON THE EXPORTS

OF EU-15 COUNTRIES FROM 1996 TO 2005

In this article the authors propose a new method for the analysis

and forecast of structural weights dynamics of an aggregate

phenomenon. This method implies the analysis and forecast of real

values’ dynamics of the structural components of the aggregate

phenomenon, structured by clusters, using their weights in aggregate

phenomenon.

By this analysis and forecast method we will obtain several

advantages regarding the quality of regression equations parameters

estimation and, implicitly, it improves the forecast quality based on such

models.

Key words: weights, regression analysis, time series forecast, clusters.

1. Introduction

In the process of analyzing and forecasting an aggregate

phenomenon’s components for obtaining real results, we must consider

the relations established: between the components of the aggregate

phenomenon and between each components and the aggregate

phenomenon because the values of an aggregate phenomenon’s

components are linked between them by aggregation operator. This link

implies a dependency relation between components and the aggregate

phenomenon.

The method suggested by the authors of this article is adjusted to

the specific of aggregate phenomenon and it is conceived to observe the

restrictions which appear in the dynamics of its components.

By this analysis and forecast method we will obtain several

advantages regarding quality of parameters estimations of equation

regression and implicitly improvement of forecast quality by using this

equation regression.

An. Inst. cerc. ec. “Gh. Zane”, t. 15, Iaşi, 2006, p. 5–26

6

Elisabeta Jaba, Ciprian-Ionel Turturean

2. Working method description

The method suggested for the analysis and forecast of economic

aggregates phenomena (e.g. UE 15 export defined by the aggregation of

country groups’ exports) implies covering the following phases:

Phase I:

- aggregate phenomenon’s analysis and forecast by using the

regression analysis [1, pp.72-89];

Phase II: - weights calculating corresponding to each component by

aggregate phenomenon for each year, from 1996 to 2005;

Phase III: - component weights grouping according to characteristics of

their dynamics, using cluster analysis [8, pp. 515-535];

Phase IV: - cluster dynamics analysis and forecasting by using the

regression method;

Phase V: - correcting forecasted weights according to a priori

restrictions;

Phase VI: - calculating the forecasted absolute values for the aggregate

phenomenon’s components, structured by clusters, for an h

forecast’s horizon, by combining the forecasted absolute

values with the forecasted weights of each cluster for the

same year.

The fundamental principle of the method presented in this article

is a model of aggregate phenomenon’s weights analysis, presented for

the first time by Professor E. JABA (1979) [3, pp. 50-100] combined

with the regression analysis applied to time series.

The literature in the field [9, pp.1-13] identifies A. Bravais

(1946), F. Galton (1984), and K. Pearson (1896) as initiators of classical

regression analysis. The issue was approached in further detail by D. B.

Pearson (1938), N. R. Draper and H. Smith(1966), R. H. Williams

(1975). The fathers of modern regression analysis are considered to be

H. Wold (1938, 1952), A. Walters (1968), G. E. P. Box and G. M.

Jenkins (1970, 1976). A reference point in the evolution of modern

regression analysis (stochastic approach) was represented by Box &

Jenkins(1976) methodology, which unified all the discoveries up to that

date in the field of the stochastic analysis of time series, affording

continuity in the modelling process [7, pp.529-531].

Method for the analysis and forecast of the components’ evolution …

7

3. Working Hypothesis

The analysis and forecasting of time series through the classical

or modern regression methods depend on the nature of the variables

analyzed in their evolution in time, with each variable being

characterized by certain variation limits and a distribution law, which can

influence the quality of the models describing them [5, pp.227-228].

Through the proposed method, the dynamics of a variable X can

be analyzed both on the aggregate phenomenon on the whole (e.g.: EU

foreign trade), and on structural components (e.g.: foreign trade of EU

member countries), grouped according to certain criteria.

In our paper, the analysis and forecast of cluster-structured

components of the studied phenomenon will be made by using their

weights (pit%), calculated according to relation (1),

p it %

x it

k

100 , i 1, k , t 1, T

(1)

x it

i 1

where: - i - represents the number of the component (group) aggregated

in variable X, i 1, k ;

- t - represents the time (moment, period) when the value of

variable X was registered, t 1, T ;

- xit - represents the value of variable X registered for component

(group) i at time (moment, period) t.

The observed variable X is:

X: {x t }, t 1, T

(2)

and its values are defined according to relation:

k

x t x it , i 1, k , t 1, T

(3)

i 1

The weights of the k components corresponding to the T periods/

time moments are presented in Table 1.

8

Elisabeta Jaba, Ciprian-Ionel Turturean

Table 1.

The X phenomenon structured by component groups,

specific for different time periods/ moments

pi1 %

pi2 %

....

pit %

....

p11 %

pi2 %

....

p1t %

....

p1t %

p21 %

pi2 %

....

p2t %

....

p2t %

....

....

....

....

....

....

pi1 %

pi2 %

....

pit %

....

pit %

....

....

....

....

....

....

pk1 %

pk2 %

pkt %

pkt %

TOTAL

100%

100%

100%

piT %

p1T %

p2T %

....

piT %

....

pkT %

100%

The presentation of the proposed method for the analysis and

forecast of cluster-structured components of an aggregate economic

phenomenon by using their weights related to on the whole is achieved in

this paper by using an example referring to the exports of the UE 15

countries for the period 1996-2005.

The following notations will be used in this article:

- X – “real value of exports” variable of EU 15 countries;

- k – number of groups/clusters;

- T – number of time periods/ moments in time;

- h – forecast horizon;

- i – number of reference group according to which the

analysis of EU 15 exports is made, i 1, k

(clusters/groups);

- t – time (moment, period) when the level of variable X was

registered, t 1, T ;

- xi,t – value of exports of group i of EU 15 countries at time t;

- xi ,t – estimated value of xi,t through regression model;

- xi ,t h – forecasted value of xi ,t for a forecast horizon h;

- Pi% – weight variable of group i of EU 15 countries related

to EU 15 total exports, i = 1, k ;

%

- pi,t – weight variable of group i of EU 15 countries related

to EU 15 total exports at time t;

%

- pi ,t – estimated value of pi,t% through regression model;

- pi%,t h – predicted value of pi,t% for a forecast horizon h.

Method for the analysis and forecast of the components’ evolution …

9

The volume dynamics in the exports of EU 15 countries and the

export weights of EU 15 component countries related total EU 15 exports

in the period 1996-2005 are presented in Table A1 and Table A2, in the

appendix.

4. Grouping of UE-15 countries

The proposed method of analysis and forecasting presents as its

distinctive stage the grouping of the evolutions of the aggregate variable

components in function of their typology. Of course, an individual

approach to the aggregate variable components is also possible (e.g.: EU

15 component countries), but their clustering according of their

evolutionary similarities is much more advantage because:

1. it attenuates the influence of random variations of weights

corresponding to elementary components by aggregation at cluster

level for the observed period, 1996-2005. This property is verified

by the fact that the defined weights must satisfy the restrictions

presented in relations (5) and (6). By grouping, more statistically

stable1 series of weights are obtained than the series of component

elements (see Table A.3). This will facilitate the identification of a

new model, in what representativity is concerned, to characterize the

evolution of the group better than the models that characterize the

evolution of each individual component;

2. it reduces the number of employed calculations and models – from

15 to 4 in the present case.

For grouping, the hierarchical cluster analysis was used through

the method of between-groups linkage, while for measuring the distances

between components, the squared Euclidian distance was applied [8, pp.

515-555]. In the present application, we opt for grouping the evolutions

of the weight of EU 15 states’ exports related to total EU 15 exports into

groups of 4 states. We have chosen a four-cluster grouping because, as

can be seen from Table A.4, a structuring into 3 clusters is insufficient,

and the structuring into 5 clusters does not bring significant changes.

1

A phenomenon is said to be more statistically stable than another if the former is

characterized by a lower variance in relation to its average. The statistical

stability of a phenomenon can be quantified by means of a variation coefficient:

v=

100 [2., p. 151]

x

10

Elisabeta Jaba, Ciprian-Ionel Turturean

The four groups of states will have the following componence

(Table A.4):

- group 1: Belgium, Denmark, Greece, Ireland, Luxemburg, Austria,

Portugal, Finland, Sweden;

- group 2: Spain, Netherlands;

- group 3: Germany;

- group 4: France, UK, Italy.

The data aggregation at a group level is made by summing the

values of the weights of EU 15 component countries’ exports within total

EU 15 exports.

In analyzing and forecasting the evolution of exports of the EU 15

countries grouped into four clusters, two approaches are available:

1. Analysis and forecasting of evolution of exports expressed in

absolute values, both at the level of each group, and at the level of

the whole volume of exports, taking into consideration the restriction

defined by relation (4).

xt

k 4

x it x1t x 2t x 3t x 4t , for

t 1, T

(4)

i 1

2. Analysis and forecast of evolution of exports expressed in relative

values. This approach involves the expression in the form of weights

(Table 2) of exports on groups of countries related to total EU- 15

exports, taking into consideration the restrictions defined by relations

(5) and (6).

-

k

100% =

p

i 1

%

it

, t

0%≤ pit%≤ 100%, i 1,k şi t=1,T

(5)

(6)

We here opt for the second approach due to the fact that:

it reduces the variation amplitude of the phenomenon (Table 3) from

(-∞, +∞) to (0%, 100%);

it reduces variance, respectively, the standard mean deviation

corresponding to the phenomenon (Table 3), which will have a

positive influence on the quality of estimates made on these values as

an alternative to value standardization.

Method for the analysis and forecast of the components’ evolution …

11

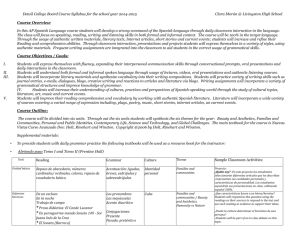

Table 2.

Dynamics of UE-15 country exports weights’ related to total UE-15

exports, structured by 4 groups for 1996-2005 period

Year

(t)

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

% for group 1 of

UE-15 countries

% for group 2 of

UE-15 countries

% for group 3 of

UE-15 countries

% for group 4 of

UE-15 countries

%

(p 1t

)

(p %

2t )

%

(p 3t

)

(p %

4t )

0,160

0,159

0,158

0,160

0,161

0,159

0,161

0,164

0,165

0,167

0,116

0,114

0,116

0,119

0,120

0,125

0,128

0,132

0,133

0,137

0,273

0,257

0,252

0,247

0,237

0,234

0,229

0,227

0,223

0,219

0,450

0,469

0,474

0,475

0,482

0,482

0,482

0,476

0,479

0,477

Source: Values calculated using data from Table A1

The only variable used in the calculations as an absolute value is

the total volume of exports of EU 15 countries.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics for the UE-15 country exports structured

by 4 groups and for the weight series corresponding for each groups

related to the total exports of UE-15 countries, from 1996 to 2005

Group 1

Weight for group 1 (p1t%)

Group 2

Weight for group 2 (p2t%)

Group 3

Weight for group 3 (p3t%)

Group 4

Weight for group 4 (p4t%)

EU - 15

Mean

Median

1410287,250

16,149

2074014,370

23,979

1088840,180

12,401

4144085,650

47,459

8718183,670

1421746,800

16,070

2087830,000

23,540

1087898,000

12,260

4272831,650

47,656

8870306,600

Standard

deviance

199214,941

0,294

122270,326

1,705

206159,166

0,819

573287,800

0,949

1094546,033

Source: Values calculated using data from Table A1 and Table A 2 according to clusters

grouping.

12

Elisabeta Jaba, Ciprian-Ionel Turturean

5. Phases of the method for the analysis and forecast of

exports made by EU 15 countries, grouped into four

clusters, based on their weights related to total EU 15

exports in the period 1996-2005

Phase I: Analysis and forecast of aggregate phenomenon through

the method of classical regression analysis. For analyzing the total

exports of EU 15 countries in the period 1996-2005, specific methods for

the analysis of time series will be used. In our example, due to the fact

that the time series has a reduced volume (10 registrations), we shall opt

for an analysis based on the method of tendency adjustment by analytical

function [5, pp. 67-81]. The selection of the best model will be made

considering the following criteria:

Criterion 1: - maximum adjusted R square (R2). This criterion will

lead to the selection of those models generating a small modelling

error in relation to the variance of the studied phenomenon and the

number of estimated coefficients in the employed regression model

[6, pp.76-78].

For variable X (exports of EU 15 component states), 4 models are

retained with the highest values of adjusted correlation coefficients

(Table 4), significantly different from zero (value sig. <0.05): the

cubic model (0.996), the square model (0.985), and the linear model

(0.992).

Criterion 2: - R square significantly different from zero. This

criterion determines the selection, from among the models meeting

criterion 1, of those models for which the value of the R square

significantly differs from zero [5, p. 79].

For testing the equality hypothesis in relation to zero of the

determination ratio, one-way factorial ANOVA is used and its

corresponding Fisher statistics (F) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Values of R square and their testing for models which describe the

dynamics of UE-15’s total exports (X), from 1996 to 2005

Model

Cubic

Quadratic

Linear

R2 Adjusted R2 F statistic

0.996

0.993

449.237

0.995

0.994

769.556

0.992

0.991

1010.099

Source: Values calculated using data from Table A1

Df 1

3.000

2.000

1.000

Df 2

6.000

7.000

8.000

Sig.

0.000

0.000

0.000

Method for the analysis and forecast of the components’ evolution …

13

Criterion 3: - criterion of parameters significantly different from

zero. This criterion will be applied to the models selected following

the successive application of criteria 1 and 2, and will result in the

retention of those models for which the values of regression equation

parameter estimators2 significantly differ from zero [7, pp.79-81]. To

this aim, the Student test will be used and its corresponding statistics t

(Table 5). In our example, only the linear model described by relation

(7) will be retained.

(7)

x̂ t = 6737669,447 + 360093,495 t

Table 5.

Testing estimated parameters for cubic model, quadratic model and linear

model which describe the tendency of the variable X

Coefficient Standard

T

Model

Sig.

value

error

statistic

3-rd order coefficient

-576.538

1605.822 -0.359 0.732

2-nd order coefficient

1266.184 26779.225

0.047 0.964

Cubic

1-st order coefficient

406932.610 129828.529

3.134 0.020

Constant

6605709.070 173209.214 38.137 0.000

2-nd order coefficient

-8246.698

3634.275 -2.269 0.058

Quadratic 1-st order coefficient

450807.178 41020.645 10.990 0.000

Constant

6556242.080 98219.599 66.751 0.000

1-st order coefficient

360093,495 11330,091 31.782 0.000

Linear

Constant

6737669,447 70301,368 95.840 0.000

Source: Values calculated using data from Table A1

Criterion 4: - criterion of the most accurate model. This criterion is

used in the case when, following the cumulative application of

criteria 1, 2, and 3, several models are obtained. In this situation, we

shall opt for the model generating the minimum sum of squares error

[1, p.20].

Criterion 5: - criterion of the simplest model. This criterion is used in

the case when, following the cumulative application of criteria 1, 2, 3,

and 4, several models are obtained. The criterion usually uses

indicators from the family of information energy criteria: Akaike

information criterion [7, p.488], Schwartz information criterion

We refer here especially to the testing of some “strategic” parameters in relation to

zero. For instance, in the linear regression equation: xt = β0 + β1 t, parameter β1 is a

strategic parameter because it gives the order of the regression equation and,

consequently, its value in relation to zero needs to be tested. Parameter β 0 cannot differ

significantly from zero and, in this case, we shall use the modified linear model xt = β1 t

2

for describing the tendency modelling of series xt, t 1, T .

14

Elisabeta Jaba, Ciprian-Ionel Turturean

[1, p.24], etc., which improve criterion 4 by penalizing the latter with

the number of coefficients included in the model describing the time

series.

Observation: In our example, it is not necessary to apply criteria 4

and 5 because there is only one potential model that describes the

tendency of variable X in the period 1996-2005. This model is

described by relation (7) and cumulatively meets criteria 1-3.

Table 6.

Export’s real values (xt) and estimate values ( x̂ t )

calculated for a 2 years forecast horizon

-

Year

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

Bill. EU (from 01.01.1999) / Bill.. ECU (to 31.12.1998) -

xt

7044446

7415942

7751446

8151819

8711406

9029207

9356548

9511032

9946401

10263591

-----------------

x̂ t

7097762,942

7457856,437

7817949,932

8178043,427

8538136,922

8898230,418

9258323,913

9618417,408

9978510,903

10338604,40

10698697,89

11058791,39

Note: Forecast is made using the linear model described by relation (7).

Source: Values calculated using data from Table A1

Based on the linear model chosen in the first part of this phase and

given the hypothesis that all conditions are preserved over modelling

time (variance and series tendency are constant), we shall make the

forecast for a prognosis horizon of 2 years. It follows that, based on the

model described in relation (7) we shall predict the value of EU 15 total

exports for years 2006 and 2007 (Table 6).

Phase II: - calculation of weights which corresponding to each

component of the aggregate phenomenon for each individual year.

Weights are calculate for exports corresponding to each EU 15

component country related to the total EU 15 exports for the period

1996-2005 (Table A.2).

Phase III: - clustering the weights of EU 15 countries’ exports

within total EU 15 exports for the period 1996-2005, according to their

evolutionary characteristics, calculated in the previous phase by using

hierarchical cluster analysis (Table A.4).

Method for the analysis and forecast of the components’ evolution …

15

Phase IV: - analysis and forecast of weight evolution of EU 15

countries’ exports, grouped in four clusters, within the total EU 15

exports for the period 1996-2005, by using modelling by analytical

function as a method of tendency analysis. Modelling the evolution of the

weight of EU 15 countries’ exports, structured into four clusters, related

to the total EU 15 exports in the period 1996-2005 will be made by

observing the approach in phase II.

For variable P1%, we retain the following models with the highest

values of the adjusted correlation coefficient (Table 7), significantly

different from zero: the cubic model (0.913) and the square model

(0.910).

Table 7.

Values of R square and their testing for models which describe the

dynamics of export’s weights (X) of UE countries’ group 1 reported to

the total of UE15 exports, from 1996 to 2005

- P1% 2

2

R

Adjusted R

F statistic df 1 df 2

Sig.

SSE

Model

Cubic

0,913

0,869

20,981

3

6 0,001 0,087

Quadratic

0,910

0,884

35,338

2

7 0,000 0,088

Source: Values calculated using data from Table 2

For variable P2%, we retain the models with the highest values of

the adjusted correlation coefficient (Table 8): the cubic model (0.991),

the square model (0.986), and the logarithmic model3 (0.985), which can

describe the weight dynamics of the exports in the 2nd group of EU 15

countries related to the total EU 15 exports.

Table 8.

Values of R square and their testing for models which describe the

dynamics of export’s weights (X) of UE countries’ group 2 reported to

the total of UE15 exports, from 1996 to 2005

- P2% R2

Adjusted R2 F statistic df 1 df 2

Sig.

SSE

Model

Cubic

0,991

0,987

224,133 3

6 0,000 0,160

Quadratic

0,986

0,982

242,053 2

7 0,000 0,204

Logarithmic 0,985

0,983

525,271 1

8 0,000 0,209

Source: Values calculated using data from Table 2

For variable P3%, we retain among the best models (Table 9): the

cubic model (0.993) and the square model (0.974) as having the highest

values of the correlation coefficient significantly different from zero.

3

xt = β0 + β1 ln(t).

16

Elisabeta Jaba, Ciprian-Ionel Turturean

Table 9.

Values of R square and testing of these for models which describe the

dynamic of export’s weights (X) of UE countries’ group 3 reported to the

total of UE15 exports, from 1996 to 2005

- P3% 2

2

R

Adjusted R

F statistic df 1 df 2

Sig.

SSE

Model

Cubic

0,993

0,990

289,493

3

6 0,000 0,068

Quadratic 0,974

0,967

131,487

2

7 0,000 0,132

Source: Values calculated using data from Table 2

The best models to describe the series of export weights in the 4th

group of EU 15 countries within total EU 15 exports for the period 19962005 (p4t%) are (Table 10): the cubic model (0.932), S4 model 4 (0.911),

and the reverse model5 (0.909).

Table 10.

Values of R square and testing of these for models which describe the

dynamic of export’s weights (X) of UE countries’ group 4 reported to the

total of UE15 exports, from 1996 to 2005

- P4% R2

Adjusted R2 F statistic df 1 df 2

Sig.

SSE

Model

Cubic

0,932

0,898

27,475

3

6 0,001 0,068

S

0,911

0,900

82,171

1

8 0,000 0,609

Inverse 0,909

0,898

79,992

1

8 0,000 0,618

Source: Values calculated using data from Table 2

For these models, the estimation and testing of the regression

equation coefficients will be made.

Table 11.

Regression equations coefficients testing for quadratic model and cubic

model corresponding to the tendency of P1% variable, from 1996 to 2005.

Coefficient

value

Model

Quadratic

Cubic

4

5

+ /t

2-nd order coefficient

1-st order coefficient

Constant

3-rd order coefficient

2-nd order coefficient

1-st order coefficient

Constant

xt = e 0 1 or ln(xt) = β0 + β1/t.

xt = β0 + β1/t.

0,017

-0,106

16,074

-0,001

0,032

-0,173

16,150

Standard

error

0,004

0,049

0,118

0,002

0,032

0,155

0,206

T statistic

Sig.

3,919

-2,152

136,458

-0,462

0,992

-1,119

78,276

0,006

0,068

0,000

0,661

0,359

0,306

0,000

Method for the analysis and forecast of the components’ evolution …

17

From the analysis of the data in Table 11, it can be noticed that

the parameters of the components of orders 3, 2, and 1 of the cubic model

are not significantly different from zero, which leads to the invalidation

of the model for value series p1,t%, t= 1996, 2005 . It follows that the

model to describe the evolution of variable P1% will be the square model

described by relation (8).

p̂ 1,t% = 16.074 -0,106 t + 0,017 t2

(8)

From the analysis of the results in Table 12 it can be seen that, for

t= 1996, 2005 , the cubic model is not validated because the

coefficient of the third-order term of the model is not significantly

different from zero. The models that pass this modelling phase are the

logarithmic and square ones. Considering that there are no large

differences between the resulted error sums of squares (Table 8) we shall

choose the square model described by relation (9) as being the best

model to describe the evolution in time of variable P2%.

p2t%,,

Table 12.

Regression equation coefficients testing for logarithmic model, quadratic

model and cubic model corresponding to the tendency of P2% variable,

from 1996 to 2005

Model

Coefficient Standard

T

value

error

statistic

1-st order coefficient

-2,308

Constant

27,465

2-nd order coefficient

0,045

1-st order coefficient

Quadratic

-1,046

Constant

27,985

3-rd order coefficient

-0,007

2-nd order coefficient

0,157

Cubic

1-st order coefficient

-1,561

Constant

28,566

*

Dependent variable is ln(p2t%).

Source: Values calculated using data from Table 3

Logarithmic*

Sig.

0,101 -22,919 0,000

0,167 164,023 0,000

0,010

4,517 0,003

0,113

-9,228 0,000

0,271 103,115 0,000

0,004

-1,916 0,104

0,059

2,665 0,037

0,286

-5,466 0,002

0,381 74,969 0,000

p̂ 2,t% = 27,985-1,046 t + 0,045 t2

(9)

18

Elisabeta Jaba, Ciprian-Ionel Turturean

Table 13.

Regression equation coefficients testing for logarithmic model, quadratic

model and cubic model corresponding to the tendency of P2% variable,

from 1996 to 2005

Model

Coefficient Standard

T statistic

value

error

1-st order coefficient

-2,308

Constant

27,465

2-nd order coefficient

0,045

1-st order coefficient

Quadratic

-1,046

Constant

27,985

3-rd order coefficient

-0,007

2-nd order coefficient

0,157

Cubic

1-st order coefficient

-1,561

Constant

28,566

*

Dependent variable is ln(p2t%).

Source: Values calculated using data from Table 3

Logarithmic*

Sig.

0,101 -22,919 0,000

0,167 164,023 0,000

0,010

4,517 0,003

0,113

-9,228 0,000

0,271 103,115 0,000

0,004

-1,916 0,104

0,059

2,665 0,037

0,286

-5,466 0,002

0,381 74,969 0,000

From the analysis of the results in Table 13, it can be noticed that,

for p3,t , t= 1996, 2005 , the following models are validated: the square

model and the cubic model. Considering the values in Table 9, we shall

choose the cubic model described by relation (10) as being the best

model to describe the evolution of variable P3% in the period 1996-2005.

%

p̂ 3,t% = 11,878 - 0,402 t + 0,119 t2 – 0,006 t3

(10)

Table 14.

Regression equations coefficients testing for inverse model, cubic model

and S model corresponding to the tendency of P4% variable,

from 1996 to 2005

Model

Coefficient

value

(-1) order coefficient

-3,264

Constant

48,415

3-rd order coefficient

0,013

2-nd order coefficient

-0,304

Cubic

1-st order coefficient

2,126

Constant

43,380

(-1) order coefficient

-0,070

S*

Constant

3,880

*

The Dependent variable is ln(p4t%).

Source: Values calculated using data from Table 3

Inverse*

Standard

error

T statistic

0,365

-8,944

0,144 337,036

0,005

2,477

0,091

-3,344

0,440

4,827

0,588

73,824

0,008

-9,065

0,003 1274,330

Sig.

0,000

0,000

0,048

0,016

0,003

0,000

0,000

0,000

Method for the analysis and forecast of the components’ evolution …

19

For variable P4%, the reverse model, cubic model and S model

(Table 14) are validated. Considering the data in Table 10, we shall

choose the cubic model described by relation (11) as being the best

model to describe the evolution of variable P4% in the period 1996-2005.

p̂ 4,t% = 43,38 + 2,126 t - 0,304 t2 – 0,013 t3

(11)

Table 15.

Real and estimated / forecasted values for the variables: P1%, P2%, P3%

and P4% for a 2 years forecast horizon, using the regression equation

models selected in the IV-th Phase

Year

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

p1,t%

16,04

15,89

15,80

15,98

16,11

15,95

16,10

16,43

16,50

16,70

---------------

p2,t%

27,28

25,72

25,18

24,68

23,68

23,40

22,93

22,75

22,28

21,90

---------------

p3,t%

11,64

11,42

11,57

11,85

12,03

12,49

12,76

13,22

13,33

13,70

---------------

p4,t%

45,01

46,95

47,42

47,45

48,18

48,16

48,21

47,61

47,90

47,70

---------------

p 1,t%

15,985

15,931

15,910

15,924

15,972

16,054

16,170

16,320

16,505

16,723

16,976

17,263

p 2,t %

26,985

26,075

25,256

24,527

23,889

23,342

22,886

22,520

22,245

22,061

21,968

21,965

p 3,t %

11,589

11,501

11,578

11,783

12,079

12,430

12,800

13,150

13,445

13,649

13,724

13,634

p 4,t %

45,216

46,525

47,388

47,887

48,102

48,114

48,004

47,854

47,744

47,755

47,967

48,463

Source: Values calculated using data from Table 2

Using the models selected for the variables export weights

corresponding to the four groups of EU 15 states related to the total EU

15 exports and assuming that all conditions remain the same throughout

modelling (constant series variance), the forecast will be made for a

prognosis horizon equal to 2 years, i.e. for years 2006 and 2007 (Table

15).

Phase V: correction of predicted weights so as to satisfy the

conditions described by relations (5) and (6). For the specific weight

values obtained through forecast for a 2-year horizon in phase III, the

observance of the conditions described by relations (5) and (6) will be

checked.

20

Elisabeta Jaba, Ciprian-Ionel Turturean

Table 16.

Coefficient adjustment values of the theoretical / forecast values for the

variables P1%, P2%, P3% and P4% according to restrictions (5) and (6)

Year

(t)

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

3

p

%

1,t

p 2,t

%

p 3,t

%

p 4,t

%

p it

100% –

3

%

i 1

15,985

15,931

15,910

15,924

15,972

16,054

16,170

16,320

16,505

16,723

16,976

17,263

26,985

26,075

25,256

24,527

23,889

23,342

22,886

22,520

22,245

22,061

21,968

21,965

11,589

11,501

11,578

11,783

12,079

12,430

12,800

13,150

13,445

13,649

13,724

13,634

45,216

46,525

47,388

47,887

48,102

48,114

48,004

47,854

47,744

47,755

47,967

48,463

– p it %

Ct

0,225

-0,032

-0,132

-0,121

-0,042

0,06

0,14

0,156

0,061

-0,188

-0,635

-1,325

0,056

-0,008

-0,033

-0,030

-0,011

0,015

0,035

0,039

0,015

-0,047

-0,159

-0,331

i 1

99,775

100,032

100,132

100,121

100,042

99,94

99,86

99,844

99,939

100,188

100,635

101,325

Source: Values calculated using data from Table 15

Should there be an infringement of the restrictions presented

through relations (5) and (6), then the deviation of the predicted values

from the restriction values will be calculated and a weighted or

unweighted adjustment of the weights obtained in phase IV will be

resorted to in order to satisfy the condition given by relation (6). The

indicators which represent the quantity with which adjustment will made

shall be called of the adjustment coefficient and marked ct. In case of an

unweighted adjustment, relation (12) (Table 16) will be used for the

calculation of ct.

4

ct

100% p̂ i%,t

i 1

4

,

(12)

where:

- p̂ i%,t represents the estimated weight value of the exports of group i

of EU 15 countries at period/time t;

- ct represents the unweighted adjustment coefficient specific to

period/moment t belonging to the forecast horizon.

Method for the analysis and forecast of the components’ evolution …

21

The correction of the predicted weights in the case of unbalanced

adjustment will be made according to relation (12) (Table 17).

Table 17.

Adjusted, theoretical and forecasted values corresponding to variables

P1%, P2%, P3% and P4%, for a 2 years forecast horizon, according to the

models selected in IV-th phase

Year

(t)

p̂1%,t

p̂ %

2, t

p̂ 3%, t

p̂ %

4, t

Ct

p̂1%,t

p̂ %

2, t

adjusted adjusted

1996 15,985 26,985 11,589 45,216 0,056 16,041 27,041

1997 15,931 26,075 11,501 46,525 -0,008 15,923 26,067

1998 15,910 25,256 11,578 47,388 -0,033 15,877 25,223

1999 15,924 24,527 11,783 47,887 -0,030 15,894 24,497

2000 15,972 23,889 12,079 48,102 -0,011 15,961 23,878

2001 16,054 23,342 12,430 48,114 0,015 16,069 23,357

2002 16,170 22,886 12,800 48,004 0,035 16,205 22,921

2003 16,320 22,520 13,150 47,854 0,039 16,359 22,559

2004 16,505 22,245 13,445 47,744 0,015 16,52 22,26

2005 16,723 22,061 13,649 47,755 -0,047 16,676 22,014

2006 16,976 21,968 13,724 47,967 -0,159 16,817 21,809

2007 17,263 21,965 13,634 48,463 -0,331 16,932 21,634

Source: Values calculated using data from Table 15 and Table 16.

p̂ i%,t adjusted = p̂ i%,t + ct ,

p̂ 3%, t

p̂ %

4, t

adjusted adjusted

11,645 45,272

11,493 46,517

11,545 47,355

11,753 47,857

12,068 48,091

12,445 48,129

12,835 48,039

13,189 47,893

13,46 47,759

13,602 47,708

13,565 47,808

13,303 48,132

(13)

Considering the relations (11) and (12), the first restriction in

relation (5) is noted to be met. It must be taken into consideration that, in

the case in which the corrected predicted value of the weight related to

the total of one group surpasses 100%, then, according to the restriction

described by relation (6), the predicted value will be given the value of

100%, and the difference between 100% and the value resulted from the

forecast is to be distributed to the other groups. The same procedure shall

be applied in the case in which, following forecast and adjustment,

respectively, weight values lower than 0% are obtained.

Phase VI: absolute predicted values of the exports of EU 15

countries grouped into clusters are obtained by multiplying the total

volume of EU 15 exports predicted for years 2006 and 2007 with the

corresponding values of the adjusted weights predicted in phase V,

according to relation (14) (Table 18).

x̂ i, t h p̂ i%,t adjusted x̂ t h ,

(14)

22

Elisabeta Jaba, Ciprian-Ionel Turturean

Table 18.

Real and forecasted values for the export’s weights of UE-15 countries

grouped in 4 clusters, for a 2 years forecast horizon, 2006 and 2007

Year

(t)

2006

2007

Year

(t)

2006

2007

x̂ t+h

10698697,89

11058791,39

p̂ 1,t%

adjusted

16,817

16,932

p̂ 2,t %

adjusted

21,809

21,634

p̂ 3,t %

adjusted

13,565

13,303

p̂ 4,t %

adjusted

47,808

48,132

x̂ 1,t+h

x̂ 2,t+h

x̂ 3,t+h

x̂ 4,t+h

1799200,024

1872474,558

2333279,023

2392458,929

1451278,369

1471151,019

5114833,487

5322817,472

Source: Values calculated using data from Table 6 and Table 17.

6. Conclusions

The method for the analysis and forecast of the evolution of

components’ weights in an aggregate phenomenon is of great use when it

is possible to break down the phenomenon into component parts, which

allows for the employment of the weights of components, structured into

clusters, related to the total, instead of absolute values.

The advantages of this method result from the reduction of the

variation field of component phenomena, with immediate implications on

the quality of model estimations and in the correction of predicted weight

values according to the restrictions defined by relations (5) and (6).

By employing the weights of each group instead of absolute

values, a new variable is introduced into the model, together with the

division by the total value of EU 15 exports, a variable which weighted

the real increase or decrease. For example, if the exports of one group of

EU 15 countries remain constant in time, but the total volume of EU 15

exports decreases, then this situation will be perceived differently at the

level of real values as compared to the weights’ level. By using weights,

a tendency increase will be perceived, while, by using absolute values,

the tendency will be perceived as stationary in time.

Another advantage of using this method results from the fact that

it is no longer necessary to update the export values of EU 15 component

countries structured on clusters, correlated to inflation rate, but only the

total volume of EU 15 exports.

Method for the analysis and forecast of the components’ evolution …

23

The aggregate variable introduced into the model by using

weights instead of real values is a restrictive variable that relates all the

real values of the components, according to relation (5).

There are, of course, disadvantages of this method, which can

appear in the case in which the evolution in the volume of exports of an

EU 15 component state is much too variable in time and the tendency

cannot be adjusted in optimum conditions; this shortcoming is done away

with by clustering the evolutions of exports of EU 15 component states.

In our paper, we have opted for the classical modelling of the

time series through the analytical adjustment of the trend (the determinist

method). If necessary, depending on the specificity of the studied series,

one can opt for more comprehensive analysis methods of the time series,

such as: exponential adjustment, ARIMA-model-based seasonal

adjustment, etc, but the phases of the methodological approach remain

broadly the same.

References

1. Diebold X., F. , 2001, Elements of Forecasting, South-Western,

Thomson Learning

2. Jaba E. , 2002, Statistica, Ed. Economica, Bucureşti, Ediţia a III-a

3. Jaba E., 1979, Forţa de muncă a femeii – zona Iaşi. Studiu de

statistică socială, Teză de doctorat, IAŞI

4. Klein L. R., 2003, Welfe A., Welfe W., Principiile modelării

macroeconometrice, Ed. Economică, Bucureşti

5. Melard G., Methodes de prevision a court term, Edition de

l’Universite de Bruxelles, 1990

6. Pindyck R. S., Rubinfeld D. L, 1991, Econometric models and

economic forecasts, Mc.Graw-Hill, Inc., New York

7. Madala G. S., 2001, Introduction to econometrics, John Wiley &

Sons, LTD., Chichester England

8. Timm N. H., 2002, Applied Multivariate Analysis, Springer Verlag,

New York Inc.

9. Stanton J. M., 2001, Galton, Pearson, and the Peas: A Brief History

of Linear Regression for Statistics Instructors, in e-review “ Journal

of Statistics Education”, Vol. 9, Nr. 3 (2001),

http://www.amstat.org/publications/jse/

24

Elisabeta Jaba, Ciprian-Ionel Turturean

Appendix

Table A1.

UE 15 export value from 1996 to 2005

– Billions EUR (from 01.01.1999)/ Billions ECU (to 31.12.1998) –

UE 15

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

217001,10 220129,40 227984,80 238233,40 251740,60

Belgium

145323,90 150414,10 155163,10 163199,90 173597,90

Denmark

1921660,50 1907246,20 1952107,00 2012000,00 2062500,00

Germany

97972,90 107103,00 108977,30 117849,50 125892,10

Greece

490446,20 505391,70 536943,10 579983,00 630263,00

Spain

1240362,40 1258310,70 1316171,70 1366466,00 1441371,00

France

58370,00

71717,60

78810,70

90612,40 104379,00

Ireland

992152,10 1052553,80 1087220,40 1127091,10 1191057,30

Italy

16215,10

16342,40

17294,30

19886,80

22000,60

Luxembourg

329315,50 341138,60 359858,70 386193,00 417960,00

Netherlands

186282,80 184287,10 191076,40 200025,30 210392,30

Austria

92690,30

98831,50 105760,30 114192,80 122270,00

Portugal

101366,30 109075,00 116643,50 120965,00 130859,00

Finland

214854,80 220161,80 222886,80 238020,20 262550,30

Sweden

United Kingdom 938269,00 1170875,10 1272142,20 1374499,80 1564573,10

TOTAL EU15

7044445,70 7415942,10 7751446,00 8151819,30 8711406,40

UE 15

2001

2002

2003

258883,50 267577,90 274582,40

Belgium

179226,10 184743,60 189640,50

Denmark

2113160,00 2145020,00 2163400,00

Germany

133104,60 143482,20 155543,20

Greece

679842,00 729021,00 780550,00

Spain

1497174,00 1548555,00 1594814,00

France

117114,10 130515,40 139097,00

Ireland

1248648,10 1295225,70 1335353,70

Italy

22572,30

24028,20

25683,80

Luxembourg

447731,00 465214,00 476349,00

Netherlands

215877,90 220687,70 226967,90

Austria

129308,30 135433,60 137522,80

Portugal

136472,00 140853,00 143807,00

Finland

247253,00 258877,90 269548,30

Sweden

United Kingdom 1602839,80 1667312,30 1598171,90

TOTAL EU15

9029206,80 9356547,50 9511031,80

Sursa: EuroStat, http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/portal/

2004

288089,10

197221,70

2215650,00

168417,20

837316,00

1659020,00

148556,50

1388870,30

27055,70

488642,00

237038,60

143028,80

149725,00

282013,50

1715941,70

9946400,60

2005

298179,80

208206,10

2247400,00

181087,50

904323,00

1710023,60

160322,00

1417241,40

29324,50

501921,00

246113,20

147395,40

155320,00

287970,30

1768549,30

10263590,50

Method for the analysis and forecast of the components’ evolution …

25

Table A2.

UE 15 export weights related to the total UE 15 export

from 1996 to 2005

–%–

Ţări ale

UE 15

Belgium

Denmark

Germany

1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005

3,08

2,97

2,94

2,92

2,89

2,87

2,86

2,89

2,90

2,91

2,06

2,03

2,00

2,00

1,99

1,98

1,97

1,99

1,98

2,03

27,28 25,72 25,18 24,68 23,68 23,40 22,93 22,75 22,28 21,90

Greece

1,39

1,44

1,41

1,45

1,45

1,47

1,53

1,64

1,69

1,76

Spain

6,96

6,81

6,93

7,11

7,23

7,53

7,79

8,21

8,42

8,81

France

Ireland

Italy

17,61 16,97 16,98 16,76 16,55 16,58 16,55 16,77 16,68 16,66

0,83

0,97

1,02

1,11

1,20

1,30

1,39

1,46

1,49

1,56

14,08 14,19 14,03 13,83 13,67 13,83 13,84 14,04 13,96 13,81

Luxembourg

0,23

0,22

0,22

0,24

0,25

0,25

0,26

0,27

0,27

0,29

Netherlands

4,67

4,60

4,64

4,74

4,80

4,96

4,97

5,01

4,91

4,89

Austria

2,64

2,49

2,47

2,45

2,42

2,39

2,36

2,39

2,38

2,40

Portugal

1,32

1,33

1,36

1,40

1,40

1,43

1,45

1,45

1,44

1,44

Finland

1,44

1,47

1,50

1,48

1,50

1,51

1,51

1,51

1,51

1,51

Sweden

3,05

2,97

2,88

2,92

3,01

2,74

2,77

2,83

2,84

2,81

United Kingdom 13,32 15,79 16,41 16,86 17,96 17,75 17,82 16,80 17,25 17,23

TOTAL EU 15 100,0 100,0 100,0 100,0 100,0 100,0 100,0 100,0 100,0 100,0

Source: Values calculated using data from Table A1

26

Elisabeta Jaba, Ciprian-Ionel Turturean

Table A3.

Descriptive statistics for weights of UE-15 country exports related to

total UE-15 export from 196-2005

Standard

Variation

UE 15*countries

Mean

Median

deviation

coefficient

Belgium

2,92

2,90

0,06

2,22

Denmark

2,01

2,00

0,03

1,35

Greece

1,52

1,46

0,13

8,53

Ireland

1,23

1,25

0,25

20,16

Austria

2.44

2.41

0.08

3.41

Luxembourg

0.25

0.25

0.02

8.67

Finland

1.49

1.51

0.02

1.59

Sweden

2.88

2.86

0.10

3.64

Portugal

1.40

1.42

0.05

3.45

Group 1 of UE 15 counties

16.15

16.07

0.29

1.82

Germany

23.98

23.54

1.70

7.11

Group 1 of UE 15 counties

23.98

23.54

1.70

7.11

Spain

7.58

7.38

0.70

9.21

Netherlands

4.82

4.84

0.15

3.09

Group 1 of UE 15 counties

12.40

12.26

0.82

6.61

Italy

13.93

13.90

0.16

1.14

France

16.81

16.72

0.32

1.90

United Kingdom

16.72

17.05

1.37

8.20

Group 1 of UE 15 counties

47.46

47.66

0.95

2.00

*Countries were grouped in 4 clusters using Hierarchical Clusters Method.

Table A4.

Grouping weights of UE-15 countries exports by clusters using

Hierarchical Clusters Method

Cluster Components

Grouping

of

Grouping of

Grouping of

UE-15

countries

by

5

countries

by

4

countries

by 3

Countries

clusters

clusters

clusters

Belgium

1

1

1

Denmark

1

1

1

Greece

1

1

1

Ireland

1

1

1

Luxembourg

1

1

1

Austria

1

1

1

Portugal

1

1

1

Finland

1

1

1

Sweden

1

1

1

Spain

3

3

1

Netherlands

3

3

1

Germany

2

2

2

France

4

4

3

United Kingdom

4

4

3

Italy

5

4

3

SPSS 13 output for Table A3 data.

CORNELIU MUNTEANU

COMPARATIVE STUDY ON MANAGERS’

TOLERANCE FOR AMBIGUITY

Tolerance of ambiguity can be defined as the tendency to perceive

ambiguous situations as desirable; intolerance is the tendency to interpret

ambiguous situations as sources of threat. An ambiguous situation is that

one which cannot de adequately structured or categorized by a person

because of the lack of sufficient cues. The problem of identifying

tendencies to perceive a situation as a source of threat may be approached

on two levels: phenomenological and operative.

Based on this psychological structure, an empirical analysis was

developed in order to compare tolerance of ambiguity between groups of

managers. A total group of 104 managers is divided into subgroups by

age, gender, functional area, hierarchical level, and entrepreneur status.

Final results indicate differences of ambiguity tolerance between age

groups, and functional groups; there are no major differences between

gender groups, hierarchical groups or entrepreneurial groups.

Introduction

Ambiguity is a characteristic which can be found in an

occupational environment in different degrees. Thus, on one hand, some

jobs are characterized by an almost continuous change of context and

expectations to which the employee must answer. On the other hand,

other jobs are characterized by a repetitive confruntation with very

similar or even identical situations.

In a similar way, people react differently to ambiguous situations.

At one extreme point there are the ones who feel comfortable and

consider the new situations to be challenges which arouse their

ambitions. They react in a favourable way when unexpected turnings

come up and they adapt quickly to changing requirements. At the other

extreme are the ones who get nervous, frustrated or even hostile to new

situations. In many cases they become aggressive to the persons whom

they consider the source of the change.

An. Inst. cerc. ec. “Gh. Zane”, t. 15, Iaşi, 2006, p. 27–40

28

Corneliu Munteanu

The conceptual frame

The tolerance of ambiguity is the tendency to perceive the

ambigous situations as desirable. Intolerance, on the other hand, is the

tendency to interpret the ambiguous situations as a threat. At least two of

the elements of this definition need further explanations, namely: 1)

ambiguous situation and 2) interpret the ambiguous situations as a

threat.

An ambigous situation is that context which cannot be defined or

described properly due to the lack of available clues. Thus, there can be

identified three categories of ambiguous situations: 1) completely new

situations, which do not present any familiar clues, 2) very complex

situations, when the number of clues to be analysed is too big for the

human intellectual capability and 3) the contradictory situations, when

the clues are equivocal and suggest the framing of the same situation in

different structural patterns. In short, the three situations can be labelled

as newness, complexity and unsolvability.

The difficulty of defining, or, more precisely, of identifying the

tendency to perceive a situation as a source of threat can be approached

in several ways. The people’s reactions to stimuli have two levels: the

phenomenological and the operational level. The first level is that of

perceptions and feelings and the second is represented by the open

expression to the natural and social objects. In other words, on one hand,

people perceive, evaluate and feel, on the other hand behave in one way

or the other depending on the relation with the environment. In order to

obtain a correct estimation of the tolerance or intolerance shown by a

person towards ambiguity there should be analysed the reactions on both

levels, the phenomenological and operational.

From this point onward, the next step is to identify the reactions

which show that the situation is perceived as a threat. The palette of

possible reactions to threats can be divided into two categories, namely:

1) obedience, acceptance and 2) arguments, disagreement. By aceptance,

the person admits that the situation is an inevitable phenomenon, that he

cannot change. As a consequence, he has nothing else to do but to accept

it as such, even if it causes cognitive dissonance. In case of disagreement,

the person makes a phenomenological or operational deed through which

he changes the reality according to his wishes. He either restructures the

information so as not to perceive the threat, or he behaves in such a

manner so as to put away the source of threat.

Thus, if one of the following types of reactions should come up,

we can deduce that the person is feeling threatened. There are four

possibilities: 1) phenomenological disagreement (suppression, denial), 2)

Comparative study on managers’ tolerance for ambiguity

29

phenomenological acceptance (anxiety and psychic distress), 3)

operational dispute (destructive and reconstructive) or 4) operational

acceptance (slip away, avoid). If we relate this to the ones mentioned

above, we can say that when these reactions are caused by new

situations, complex or impossible to solve, the person shows intolerance

of ambiguity.

The level of tolerance of ambiguity can be considered a

permanent variable. The description of the reactions caused by different

levels of tolerance can be done on three steps, namely:

Low tolerance. The person feels at difficulty when facing the

ambiguous situation and shows excessive anger and frustration. He

adapts very slowly and expresses verbally the hostility towards the

people in leading positions, who control the evolution of the

situation.

Average tolerance. The person reacts with moderate anger and

frustration to ambiguous situations but adapts to them with an

acceptable speed. The personal, interpersonal or group reactions

due to the psychic discomfort are not noticeable. The people who

are in leading positions can be the target of mean allusions,

comments or sarcastic jokes – which do not go beyond the limit of

aggressiveness.

High tolerance. The person reacts without any anger or frustration.

He adapts quickly to the change, without any consequences to the

personal, interpersonal or group onsequences. On the contrary, he

feels even more comfortable when the context is changed.

The issue of tolerance towards ambiguity and the behaviour

implications has been approached in different fields. There are

approaches from the educational field, which discuss the control of

ambiguity when working with pupils and students. (Frenkel-Brunswik,

1949; Owen and Sweeney, 2005). There are also approaches which

regard the reactions in different contexts, the most frequently met one is

the field of financial placement. This kind of studies analyse the

differences between the reactions of the two sexual groups (Schubert,

Gysler, Brown and Brachinger, 2000).

This study limits its investigation area to the level of the business

men, on the managerial levels 1 (general manager), 2 (deputy manager)

and 3 (department manager).

30

Corneliu Munteanu

Research hypotheses

This study aims to investigate whether there are differences in

the attitude towards ambiguity of the persons from management

positions in business.

The first issue regards the differences in tolerance depending on

age. As people grow older, the physiological paramenters are changing,

especially the ones related to information processing. The volume of new

information which can be processed in a time unit is decreasing.

Consequently, older people feel a stronger sensation of discomfort in

ambiguous situations compared to younger persons.

H1: The level of tolerance of ambiguity differs according to the age

group

A second issue refers to the existence of differences in tolerance

depending on sex. Previous studies have proved that there are such

differences. But the meaning of the differences differs depending on

the decisional context. It has been noticed that women are more

intolerant to ambiguity when the decisional context is related to

investment, but they are more tolerant when the context is related to

insurance.

H2: The level of tolerance of ambiguity differs according to sex

The third issue regards the existence of differences depending on the

field. The management positions were divided into three categories:

technical, financial-accountancy and management-marketing. The

variability of the contexts is very different between the three fields.

At one extreme there is the financial-accountancy field, in which the

situations present a very repetitive character, novelty and ambiguity

are rarely met. At the other extreme there is the managementmarketing field. In this field, novelty is almost permanent: new

clients, new products, new competitives, new employees. The

technical field occupies the intermediary level; novelty and

ambiguity are present, but more rare than in the field of

management-marketing. As a consequence, it is expected that

persons with different levels of tolerance of ambiguity will choose

the three fields.

H3: The level of tolerance of ambiguity differs according to the field:

tehnical, financial-accountancy, management-marketing

The fourth issue regards the analysis of the differences depending on

the hierarchical level. Thus, the degree of ambiguity that a leading

person has to face increases along with the hierarchical level. The

persons on top positions must face much more complex situations

Comparative study on managers’ tolerance for ambiguity

31

than the persons from lower level. A general manager must have

control over technical problems, as well as over economic or psychosocial problems. A technical manager faces only technical problems,

while a department manager has an even more limited level of

problems.

H4: The level of tolerance of ambiguity differs according to the

hierarhical level

In the end, the last issue regards the existence of differences

depending on the entrepreneurial status. Unlike managers, the

entrepreneurs face a higher level of ambiguity. We consider first of

all the uncertainty from the moments at the beginning of the

business, an uncertainty that the managers do not have to face. Also,

there are differences as regards the level of responsability. An

entrepreneur undertakes the responsibility related to all categories of

people included in the organization; the manager is responsible only

in front of the shareholders.

H5: The level of tolerance of ambiguity differs according to the

entrepreneurial status

We present in the following the empirical investigation that was

done starting from the five hypotheses of research.

The research method

Taking into consideration the fact that the tolerance of ambiguity

can appear at phenomenological level as well as operational, the most

appropriate method to test each of the five hypotheses is the survey. The

population included in the survey are the managers from the three

hierarchical levels, from companies of private capital as well as

companies with state capital or joint ventures.

Sample

Taking into consideration the exploratory character of research of

the survey, there was chosen a sample of more than 100 persons who

work in private companies, as well as in public companies (firms or )

from the town of Iasi. At the end of the data gathering, 104 persons out of

the 117 participants proved to have the characteristics of the population

to be surveyed. The other 13 persons were working either for non-profit

organizations or they were from the managerial level 4 (office managers)

and they were excluded from the data processing.

32

Corneliu Munteanu

The structure of the final sample is the following:

by sex: 35 women (33.7%) and 69 men (66.3%);

by age: 41 persons under 35 years old (39.4%), 23 persons between

36-45 years old (22.1%), 31 persons between 46-55 years old

(29.8%) and 9 persons over 55 years old (8.7%);

by level of education: 1 high school graduate (1.0%), 69 university

graduates (66.3%), 27 following or graduates of post-graduate

programmes (26.0%) and 7 following or graduates of PHD

programmes (6.7%);

by field of activity: 33 persons from the technical field (31.7%), 19

persons from Finances-Accountancy (18.3%) and 35 persons from

Management and Marketing (33.7%). The general managers were

not included in a certain field (17 persons).

by hierarchical level: 17 general managers (16.3%), 40 deputy

managers (38.5%) and 47 department managers (45.2%);

by entrepreneurial profile: 19 entrepreneurs (18.3%) and 85

managers (81.7%). The persons who own shares, but who have

become shareholders after the state company turned into private

company, were not given the status of entrepreneurs.

by type of company: 37 persons work for state companies, 48 în

private companies şi 19 in joint ventures (private and state property)

The selection of the companies to be involved was done

according to the possibility to approach the general manager, whom was

asked to cooperate in the accomplishment of the study.

Data gathering

For the data gathering, it was necessary to go to the premises of

the involved companies. Each person was interviewed alone, so as not to

appear negative influences from the social environment. At the beginning

of the meeting there was presented the purpose of the study – namely, a

comparative study on different categories of managers – it was also

mentioned that there would not be required confidential information and

they were asked whether they agreed to participate. Once the agreement

was given, there was filled in the questionnaire which contains 19 basic

items and a set of identification items.

Comparative study on managers’ tolerance for ambiguity

33

The research instrument

In order to make the study operational, the research instrument

was a questionnaire with 19 items formulated on the Likert scale, with 5

steps. The questionnaire is an adaptation of the set of questions proposed

by Budner (1962), a set which is often mentioned in the articles and

studies from the same field (Ghosh and Crain, 1993; Ghosh and Manash,

1992, 1997).

If the interviewed person accepts the challenge of novelty,

complexity or unsolvability, we can deduce he/she is tolerant to

ambiguity. If, on the contrary, he/she rejects the challenges which come

up in these three situations, we deduce he/she is intolerant to ambiguity.

Acceptance or rejection can appear either on phenomenological or on

operational level..

For the ranking, the possible answers were given numbers from 1

to 5, taking into consideration the answer expected in case of tolerance,

so that a TOLAMB score will show the existence of high tolerance of

ambiguity, and the small score will show low tolerance.

We present in the folowing part, as an example, two of the items

which were used, for which the interviewed person was asked to mention

the degree in which he agreed or not to each statement.

"I like more the parties or the business cocktails where there

are many unknown people, rather than the ones where I know

almost all the guests.”

disagreement disagreement neutral

agreement

agreement

total

average

average

total

From the point of view of the tipology of the reaction to ambiguity, this

item presents itself in the following way:

Situation

level

Reaction of

Tolerant

intolerance

answer

complex,

phenomenological Fight against

agreement

new

1. „I would be afraid to pilot alone an orbital space ship.”

disagreement disagreement neutral

agreement

agreement

total

average

average

total

From the point of view of the tipology of the reaction to ambiguity, this

item presents itself as follows:

Situation

level

Intolerant

Tolerant

Reaction

answer

new

phenomenological Fight against

disagreement

34

Corneliu Munteanu

All the 9 items describe this kind of situations, characterized by novelty,

complexity or unsolvability.

Results

There was calculated a global score for TOLAMB tolerance, by

adding the point obtained for all the 19 items.

1. The first comparison of the TOLAMB scores is done between

the age groups, in order to see whether there are significant differences.

The TOLAMB averages for the age groups are shown in the table below.

Table no 1

TOLAMB score for age groups

Age group

under 35 years old

36-45 years old

46-55 years old

56 years old and above

Number of

interviewed

persons

41

23

31