Lynne remembers Van Damm, when she was the very young age of

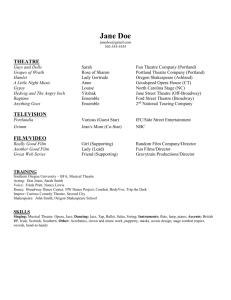

advertisement