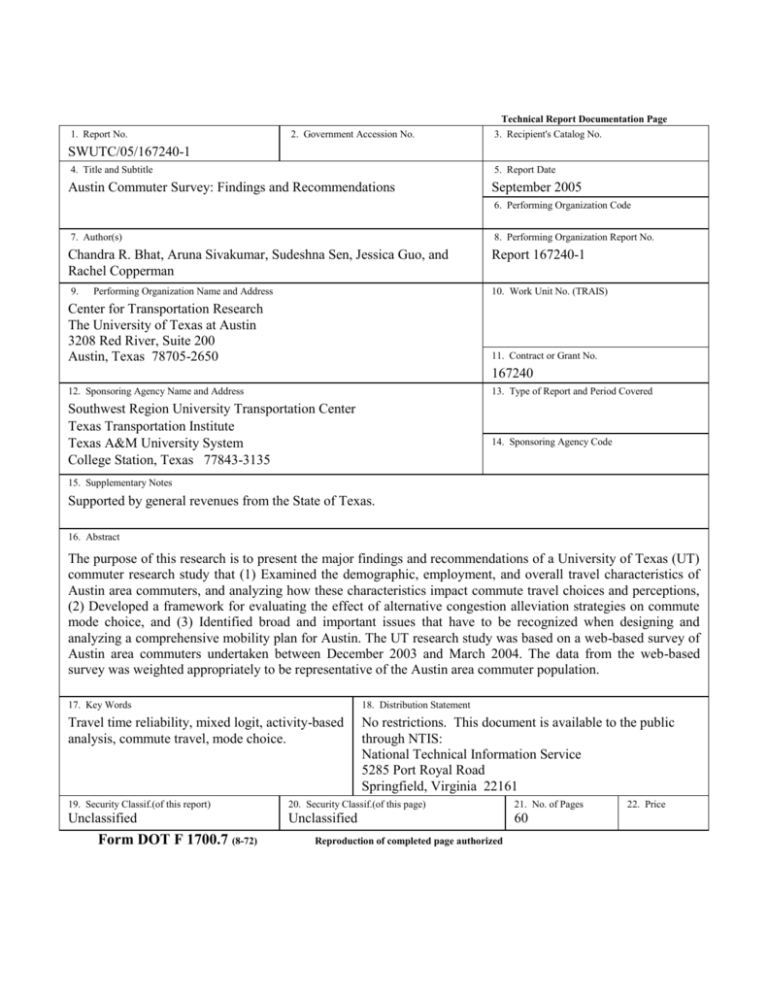

MS Word version - The University of Texas at Austin

advertisement