Chapter VII: Palliation

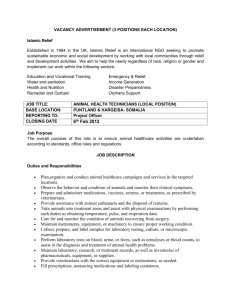

advertisement

Chapter VII: Palliation The experience of and response to pain • Pain • Pain and suffering • Care givers’ responses to patients’ pain The moral imperative to relieve pain: Autonomy, beneficence and consent Physician-assisted suicide • Care giver’s role • Doctrine of double effect • Supreme Court decisions The end of life and palliative care • Background • Evolution of the care giver role • Goals of care • Palliative care definition and philosophy Mrs. H has been a resident of a long-term care facility for many years, during which her COPD, diabetes and osteoarthritis have become more severe. She is now confined to a wheelchair because of the intense pain in her back and hips, which she often describes as excruciating. The mild analgesics, including Tylenol, that have been prescribed do not bring relief and she has become increasingly immobilized, withdrawn and depressed. When her nephew, Dr. A, visited recently, he was alarmed by the deterioration he saw in his aunt. The person he remembered as vibrant and active was now saying, “I have no life. All I have is pain.” When he asked what she would like to be able to do that the pain prevented, he expected her to talk about missing her hiking, gardening and painting. Instead, she replied, “Sleep. I don’t remember the last time I was able to sleep without being awakened by pain.” Dr. A requests a meeting to discuss his aunt’s pain management. I. The Experience of and Response to Pain A. Pain Despite its subjective quality, the experience of pain is both real and reverberating. As one writer describes it, Pain is dehumanizing. The severer the pain, the more it overshadows the patient’s intelligence. All she or he can think about is pain: there is no past pain-free memory, no pain-free future, only the pain-filled present. Pain destroys autonomy: the patient is afraid to make the slightest movement. All choices are focused on either relieving the present pain or preventing greater future pain, and for this, one will sell one’s soul. Pain is humiliating: it destroys all sense of selfesteem accompanied by feelings of helplessness in the grip of pain, dependency on drugs, and being a burden to others. In its extreme, pain destroys the soul itself and all will to live. (E.L. Lisson, “Ethical Issues Related to Pain Control,” Nursing Clinics of North America, 22 (1987): 654.) In the face of advances in science and technology, one care giver mandate remains constant and compelling—the relief of pain. Even when cure is impossible, the duty of care includes palliation. Moreover, the centrality of this obligation is both unquestioned and universal, transcending time and cultural boundaries. People often distinguish between physical and spiritual or emotional pain, that is, between pain that is physiological or psychological in origin. However we speak of it, the relief of pain is regarded as a primary moral goal of medicine because of its intimate connection with patient well-being. Although universally acknowledged, pain is a complex phenomenon for both the patient and the physician, influenced as much by personal values and cultural traditions as by physiological injury and disease. Indeed, if the perception of and response to pain are to be understood in a useful way, they must be examined in the context of culture, gender, power imbalances, morality and myth. These factors take on special importance in the health care setting, where pain becomes an interpersonal experience between the sufferer and the reliever. How pain is signified by the patient and understood by the provider determines in large measure how it is valued and, ultimately, how it is treated. B. Pain and Suffering An important theme that threads its way through the bioethics analysis is the distinction between pain and suffering. In a classic 1982 article called “The Nature of Suffering and the Goals of Medicine,” Dr. Eric Cassell wrote about pain as a physiological response of the body and suffering as an existential assault on the person. He described how one could experience pain without suffering when the goal is a noble or joyous one, using as an example the pain of childbirth. Conversely, a person can suffer without physical pain when he feels the disintegration of his personhood and his sense of control. When pain and suffering are closely related, Cassell claims, it is for one or more of the following reasons: the pain is overwhelming; the patient does not believe the pain can be controlled; the source of the pain is unknown; or the pain is apparently without end. Suffering is a threat, not merely to patients’ lives, but also to “their integrity as persons.” Only when one’s continued existence is threatened in this way can the experience of pain properly be said to cause suffering. Thus, when patients are told their pain cannot be managed, diminished, or controlled, they frequently experience suffering, because they believe their personal intactness is jeopardized. In some instances, emotional isolation adds to patients’ suffering, as when the physician suggests that the pain is only imagined. It is impossible to spend any time in a clinical setting without recognizing this distinction and it is one of the key issues in bioethics consultation. Patients are often asked to endure pain in the pursuit of a cure or a remission and, in weighing the benefits and burdens of a proposed treatment, the balance of current discomfort for future relief seems an ethically appropriate one. The calculus is different when the intervention will impose pain or suffering with no benefit. Likewise, suffering without pain is evident in the patient with aphasia that prevents him from communicating with his family, the trained athlete who can no longer care for her most basic physical needs, the father who must accept that his infant will never develop, and the artist trying to create faster than her eyesight is failing. C. Response to Patients’ Pain Ms. P is a 27-year-old African American woman with sickle cell anemia, admitted to the ER in sickle cell crisis. She has severe pain in her thighs, arms, hands and feet. She is dehydrated and anemic. An ER resident orders an injection of Demerol for pain and a normal saline IV for hydration. She is admitted to the hospital. Following admission, Ms. P questions the nurses closely about her medication and continues to complain of pain. During morning rounds the next day, the medical team discovers that the patient knows a great deal about her disease and its management. When she is not having a crisis, she is able to use a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, such as Motrin, to manage her pain. She claims that, during a crisis, intravenous morphine provides the most effective pain relief and she asks that she be given this drug rather than Demerol. She even suggests dosages and schedules. In the past, she says, she has self-administered the morphine with a patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) pump, which allows her to have a steady drip on a round-the-clock (RTC) basis, as well as supplementary morphine on a prescribe-as- needed (PRN) basis for breakthrough pain. The medical team is somewhat dumbfounded by Ms. P’s request. The attending tells her that, while her suggestion is considered, Demerol on a PRN basis will be continued. He also asks who has treated her in the past so that he can confer with the physicians who know her well. Ms. P says that she has no primary care physician, but provides the names of several hospitals where she has received care during the past few years. After leaving Ms. P’s room, the team discusses her case. One resident questions her detailed request for particular type of pain medication. He is concerned that she may be an addict trying to get a fix and that she likes the euphoria from the morphine. Another resident points out that Demerol provides a more euphoric effect than a morphine drip or other opioids, such as methadone. Just as patients’ attitudes about and responses to pain are affected by their personal and cultural values, so are those of their care providers. For example, physicians' clinical judgments about pain are influenced by group-based factors, including age, gender, race, ethnicity and physical appearance, with more attractive patients perceived as experiencing less pain than those who are unattractive. Studies have found that, because women are often seen as emotionally labile and prone to exaggerating pain complaints, they are given analgesia less frequently and sedation more frequently than male patients. Likewise, younger patients of both genders tend to receive more frequent pain medication than their elders. Physicians have been found to respond differently to the pain of patients from ethnic backgrounds different from their own. The balance of power between provider and patient is yet another theme in the pain management interaction. So long as therapeutic control is vested in the care giver, the patient remains the passive victim of pain, a supplicant in the standard p.r.n. regimen. Physicians’ responses to their patients’ pain are also shaped by their understanding— often misunderstanding—of pain and the agents for its relief. Numerous studies have shown that inadequate professional education and susceptibility to misconceptions about opioid addiction and related regulations undermine effective analgesia. These misconceptions are also shared by the lay public. Americans tend to reject what they believe to be effective medicinal pain relief because they fear overreliance and/or addiction. These fears, plus concerns about legal liability, are reflected in the stringent laws regulating drug prescription and the suspicions of health care providers who see patient requests for pain relief as drug-seeking behaviors related to addiction. Reluctance to provide adequate pain medication has also been related to physician fears that analgesics, especially opioids, will “kill patients.” The unsurprising result is the routine undermedication of even terminally ill patients. These findings may have their roots in beliefs that are common to Western cultures. It has been suggested that the current standard of treating acute pain responsively rather than preventively stems from two persistent Western myths: (1) enduring pain is a character-building, moral-enhancing endeavor; and (2) patients who receive pain medication become addicted to the drugs. II. The Moral Imperative to Relieve Pain: Autonomy, Beneficence and Consent The relief of pain is more than a professional obligation, it is a moral imperative. Pain and its relief implicate two of the fundamental ethical principles—autonomy and beneficence—and discussions of pain management and informed consent highlight the tension between the two principles. Principled analyses of the therapeutic relationship suggest that it is the dual obligation of physicians to respect and promote the autonomy of their patients and to protect and enhance their well-being. Relieving pain is considered a conditional obligation, something care givers ought to do unless some other duty or moral consideration takes precedence. One such consideration is the refusal of a decisionally capable patient to have her pain relieved. For example, if a patient with the capacity to make health care decisions says she wants the pain to continue because for her it has redemptive meaning, then the obligation to relieve pain is overridden. The patient is saying that, although in pain, she is not suffering or that the suffering is chosen and accepted. A more common reason for electing to experience pain is the choice of cognition and affective response over relief. Many patients refuse higher doses or more potent pain medication because they do not want to chemically compromise their intellectual and emotional awareness. For these individuals, the choice is a deliberate value-based balance between relief of pain and erosion of personality. But suppose a patient is incapacitated and clearly in pain. Should efforts always be made to provide relief or is consent necessary? While honoring the wishes of a capable individual shows respect for the person, withholding relief from one who cannot decide or communicate would be a form of abandonment, indefensible for care givers. Compassion, then, is the basis of a moral presumption favoring pain relief for the patient who can no longer choose or whose intent is in question. Pain is not always disvalued, but it is something we need a compelling reason not to treat. The most humane approach, and the one to which physicians are disposed, is to relieve pain until clear evidence of patient refusal is forthcoming. Fortunately, in the context of pain management the twin duties of respect for autonomy and beneficence are not mutually exclusive or even necessarily conflicting. Rather, principled and compassionate caring embraces both the respect for and the protection of persons. Thus, no expressed informed consent is required precisely because providing relief from pain is central to the very notion of healing and, for that reason alone, it requires no additional justifications. Let us return to Mrs. H, the nursing home resident with multiple medical problems and severe pain. Her suffering is persistent and significant enough to interfere with her activities. Despite her best efforts, her pain has become the focus of her attention and has profoundly impaired her quality of life. Far from rejecting pain medication, she is clearly asking for relief. Her care team has both a clinical and an ethical mandate to carefully assess her pain, discuss with her the benefits, burdens and risks of the analgesic options, and provide her with sufficient analgesia to relieve her suffering. The team should also identify and address the barriers to adequate pain relief that prevented her symptoms from being appropriately managed. III. Physician-Assisted Suicide The lab results of Diane’s blood tests confirmed Dr. Quill’s worst fears—she did indeed have leukemia. His obvious distress reflected both the disappointment common to physicians whose patients contract life-threatening illnesses, as well as the special concern he had for someone who had been his patient for many years and with whom he had developed a close and trusting therapeutic relationship. In addition, he had great admiration for the strength and determination with which she had overcome significant physical and emotional difficulties. In the process, she strengthened her relationships with her husband, college-age son, and friends and reinvigorated her business and artistic work. Now they faced this devastating news together, going through the confirmatory tests and discussing with her husband the various options, including chemotherapy, followed by radiation and possible bone marrow transplants. Even with the most aggressive treatment regimen, the chances for long-term survival were 25%; the certain outcome of no treatment was death within a few months. After considerable discussion and reflection, Diane decided not to undergo chemotherapy because she was convinced that she would not survive it and that the quality of whatever time she had left was more important than the unlikely benefits of treatment. Despite Dr. Quill’s misgivings and her family’s attempts to persuade her to change her mind, she remained steadfast in her determination to make the most of her time at home. Ultimately, her family and physician reluctantly supported her decision. Dr. Quill had known throughout their relationship that, for Diane, regaining and maintaining control of her life was a central value. Now he realized that being in control of her dying was just as important to her as she faced the end of her life. She became preoccupied with concern about deteriorating, lingering, being helpless and in pain. Her anxiety about the prospect of a protracted death became so severe that it threatened to undermine the quality end of life she had as her goal. She asked Dr. Quill to help her avoid the painful, debilitating and dehumanizing ravages in store by providing drugs that she could take to end her life when she chose. She was convinced that having the ability to control her death would give her the dignity and peace of mind that she needed. After extensive discussion and psychiatric consultation, Dr. Quill acceded to Diane’s unwavering determination, prescribed the barbiturates and provided the information necessary for her to take her own life. She was able to spend the next several months focusing on the people, relationships and activities that were most important to her. She received aggressive palliative treatment but, eventually, she determined that the benefits of life no longer outweighed its burdens. Her death was on her own terms, at the time and in the manner of her choosing. Yet, concerns about potential legal liability prevented her from having her family or physician with her at the end and she died alone. A. Care Giver’s Role Discussions of pain, suffering and death lead inevitably to the subject of physicianassisted suicide. “Assisted death” as a synonym for voluntary euthanasia remains illegal in all states but Oregon. While all states have decriminalized suicide, most states punish those who assist another to commit suicide, although these prosecutions are rare and unsuccessful. The ethical analysis of assisted dying addresses the issues of physician obligations, individual autonomy, public policy and the ethical imperative to relieve suffering. At the very core of the healing professions is the principle of nonmaleficence, the maxim “Do no harm.” The concept of killing patients, however passively, is an anathema to those who devote themselves to promoting and protecting life. Yet, there has been a perceptible shift in the dialogue. Many have come to see assisting a rational suicide as the last act in a compassionate continuum of care and forcing the patient to take that final step alone as an act of abandonment. Others argue that, in vulnerable and disempowered populations, such as the poor and elderly, the right to die may become the obligation to die as a way of relieving family or society of the unwanted burden of their care. Ultimately, there is concern that the individual, morally justified act of assisted suicide could become the generalized policy of euthanasia. A critical distinction is the doctrine of double effect, which holds that a single act having two foreseen effects, one good and one bad, is not morally or legally prohibited if the harmful effect is not intended. The doctrine, which has its basis in Catholic theology, requires that: • the act itself is not wrong; • the good effect is the result of the act and not the bad or harmful effect; and • the benefits of the good effect outweigh the foreseen but unintended bad effect. All three conditions are essential to prevent the doctrine from being abused or perverted in an effort to justify actions intended to cause harm. Correctly applied, however, the doctrine of double effect permits the administration of sufficient opioids to relieve pain at the end of life, knowing that it could depress respirations enough to hasten death. Providing analgesia is not inherently wrong; the desired good effect (relief of pain) is the result of the act (providing analgesia), not the bad effect (death); and the benefits of relieving pain at the end of life outweigh the foreseen but unintended hastening of death. Using the rationale of the doctrine of double effect, the intervention is both approved and protected. B. Supreme Court Decisions In June 1997, the United States Supreme Court ruled in two cases seeking to turn the right to refuse treatment into a right to assisted death. The plaintiffs in Washington v. Glucksberg claimed that the Fourteenth Amendment due process clause could embrace the right to determine the time and manner of one’s death. The plaintiffs in Vacco v. Quill claimed that, under the Fourteenth Amendment equal protection clause, terminally ill patients without the opportunity to reject life-sustaining measures should have the same right to end their lives. The Supreme Court rejected both arguments in two rulings that have more to do with palliative care than assisted suicide. The Court held that, while there is no constitutionally protected right to assisted suicide, there is a protected interest in pain relief. The Court reaffirmed the doctrine of double effect, saying that it is both legally and ethically appropriate to give terminally ill patients as much medication as necessary to relieve pain, even if the effect is to hasten death. The Court also strongly reaffirmed the distinction between foregoing life-sustaining treatment and assisted suicide. Finally, the decisions indicated that if states did not statutorily make it easier and less threatening for physicians to provide adequate analgesia to patients who need it, the Court would not rule out the possibility of revisiting the issue of assisted suicide in a future case. The importance of these rulings to compassionate care cannot be overstated. IV. A. The End of Life and Palliative Care Background Among health care’s most important challenges is the need to improve palliation. Both the public and professionals are troubled by the reality of overtreated disease and undertreated pain, especially at the end of life. Considerable research and literature demonstrate that the health care profession does a shockingly inadequate job of pain management and that many people who request assistance in killing themselves are actually asking for the assurance of pain relief. Part of the blame falls to the legal and lay communities that have created a climate in which physicians are reluctant to provide drugs for fear of legal liability, even though there has never been in this country a successful prosecution in a case of patient death when a narcotic was given with the intent to relieve pain. It should be a matter of concern when the debate centers on the questionable constitutional right of terminally ill patients to receive physician assistance in ending rather than easing their lives. B. Evolution of the Care Giver Role Providing comfort at the end of life is neither a departure from nor an abdication of the traditional responsibilities of medicine. Indeed, it is worth remembering that, until the middle of the last century, the cure of disease and the prevention of death were not the primary therapeutic goals because they were largely beyond the capability of those who ministered to the sick; rather, they were the hoped-for by-products of efforts aimed at easing the discomfort of the afflicted. It was only with the relatively recent advent of biotechnology that “care givers” came to be seen as “cure givers,” and comfort came to be seen as what was left when there was “nothing more to do.” In the process, death was perceived as a failure of skill and dying made professionals uncomfortable. Now, increasingly sophisticated science and skill present the biotechnological imperative, and we are faced with questions of when, how and even whether to die. C. Goals of Care For this reason, a bioethics analysis begins with the question, “What is the overall goal of care for this patient?,” not “What is the goal of this intervention?” The tendency to do everything makes it easy to justify this one treatment and then the next and then the next. The patient’s interest is better served by asking, “Where does this treatment fit into the overall plan of care? If it advances the goal, then we should begin or continue it. If not, we probably have no business doing it.” Using this approach permits the initiation of a life-sustaining treatment, such as dialysis or ventilatory support, for a limited time with the clear understanding that, if it does not achieve the desired effect, it can be discontinued. Keeping the goals at the center of care planning also permits a wider range of therapeutic options, which is especially important at the end of life. Interventions can and should be evaluated in terms of what they can accomplish for the patient rather than categorized according to conventional labels. For example, surgery, radiation or antibiotics can be appropriately considered for a dying patient when it is clear that the goal is comfort rather than cure. When patients are beyond the reach of medicine’s ability to improve their quality of life, palliative care can profoundly affect the quality of their death.. D. Palliative Care Definition and Philosophy Clinical ethics consultation services and ethics committees are regularly confronted with end-of-life issues. As more institutions establish dedicated palliative care teams, the collaboration between the two services creates a powerful set of resources to benefit patients at or approaching the end of life. The following definition and philosophy of palliative care, including principles and clinical guidelines, were developed by the Bioethics Committee at Montefiore Medical Center. 1. Definition Palliative care is active intervention, which has as its goal the achievement of maximum comfort and function of the total patient. While palliation can and should always be an integral part of the entire spectrum of patient care, it stands alone as the care for the patient who has been diagnosed with an irreversibly deteriorating or terminal condition and for whom curative treatment is no longer the goal of care. Palliative care shares with cure-oriented care the qualities of plan-driven activity, purposeful organization and evaluation, range of treatment options, care giver-patient engagement and collaborative decision making. The only distinguishing characteristic is the goal of care: palliation has compassionate caring rather than cure as its goal. Because palliation remains on the care continuum after cure is no longer the goal, it may encompass particular comfort measures posing risks to life that might not have been acceptable when cure was still the goal of care. 2. Clinical Issues • Most decisions, particularly about health care matters with significant implications, are determined by how the issues are framed. This is perhaps most apparent in relation to end-of-life care. The willingness of patients and families to embrace or even accept the notion of palliative care will depend on whether it is presented as a defeat or an opportunity to make the most of the time remaining. Withholding or withdrawing life-sustaining measures can be seen as depriving the patient of needed treatment or protecting the patient from unnecessary and burdensome interventions. • When patients are aware at any level, their interests are paramount. When patients are beyond help and beyond suffering, the interests of their loved ones may be elevated. When the family of a comatose patient says, “We can’t let go just yet. His daughter is coming from California on Sunday,” it may be appropriate to say, “Let’s wait 48 hours before discontinuing life support. But let’s be clear about why we are doing this—not because we are hoping for a miracle cure for him, but because you need the time.” • There is a difference between truth telling and truth dumping. Most dying patients, including children, deserve to have their questions answered and not be protected into isolation because others are uncomfortable. This is precisely the time patients need to know they are not alone. • Patients and families who insist on “doing everything” should trigger an analysis of whose needs are being met and who is being burdened. There is no obligation to provide ineffective treatment and no right to impose pain and suffering on the patient just to exhaust every therapeutic possibility. 3. Philosophy Promoting the patient’s physical and emotional comfort is always a therapeutic goal. There is a time when this becomes the therapeutic goal—a time when care, not cure, becomes paramount. Care givers have a responsibility to communicate to patients and families their commitment to promoting patient comfort, and to provide reassurance that the patient will not be abandoned. Care givers have a responsibility to shift the focus from the interventions that are being discontinued to all the comfort measures that will be continued or initiated. Care givers have a responsibility to recognize when the goal of care shifts from cure to comfort, and to engage patients, families and other care givers in discussing and planning for the change in orientation. Palliation is a multidisciplinary undertaking, involving the patient and family, and calling on the efforts and skills of medicine, nursing, pain management, bioethics, social services, pastoral care, and recreational therapy. • Because notions of health, illness, pain and relief are perceived and interpreted according to the background and traditions of patients and care givers, knowledge of and respect for culture and religion are integral to the responsibilities of care givers. • Palliation is not all that is left when there is nothing left to do. • Palliation is not a response that begins when the patient is in pain. • Palliation is a philosophy and a set of active behaviors that continue throughout the therapeutic process, becoming the single focus of care giving for the patient and family as death nears. Conclusion The role of the physician—to promote the patient’s well-being—takes on a heightened intensity at the end of life. In times of death and dying—when patients and their loved ones look to you for skill and guidance—you are sometimes most ethical and compassionate by supporting a pain-free, peaceful and dignified death as a legitimate care goal. References: American Board of Internal Medicine: Committee on Evaluation of Clinical Competence. Caring for the Dying: Identification and Promotion of Physician Competency. (Philadelphia: American Board of Internal Medicine, 1996). Bascom PB, Tolle SW. “Responding to Requests for Physician-Assisted Suicide,” JAMA 2002;288(1):91-98. Cassel CK , Vladeck BC. “ICD-9 code for Palliative Care,” New England Journal of Medicine 1996;335(16):1232-12-33. Cassell E, “The Nature of Suffering and the Goals of Medicine,” New England Journal of Medicine 1982;306(11):639-645. Dworkin R. “Assisted Suicide: The Philosophers’ Brief, Introduction” in Ethical Issues in Modern Medicine, Sixth Edition. Steinbock B, Arras JD, London AJ, eds. Boston: McGraw-Hill, 2003, pp. 382-385. Dworkin R et al. “The Philosophers’ Brief” in Ethical Issues in Modern Medicine, Sixth Edition. Steinbock B, Arras JD, London AJ, eds. Boston: McGraw-Hill, 2003, pp. 386394. Emanuel LL. “Facing Requests for Physician-Assisted Suicide: Toward A Practical and Principled Clinical Skill Set,” JAMA 1998;280:643-647. Lopez SR “Patient Variable Biases in Clinical Judgment: Conceptual Overview and Considerations,” Psychological Bulletin 106 (1989): 184-203. Post LF , Blustein J, Gordon E, Dubler NN. “Pain: Ethics, Culture and Informed Consent to Relief,” Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics 1996;24:348-359. Post LF, Dubler NN. “Palliative Care: A Bioethical Definition, Principles and Clinical Guidelines,” Bioethics Forum 1997;13(3):17-24. Steinbock B, Arras JD, London AJ. “Moral Reasoning in the Medical Context,” in Ethical Issues in Modern Medicine, Sixth Edition, Steinbock B, Arras JD, London AJ, eds. (Boston: McGraw- Hill, 2003), pp. 1-41. Quill TE. “Death and Dignity: A Case of Individualized Decision Making,” New England Journal of Medicine 1991; 324(10):691-694.