concurring opinion of judge aa cançado trindade

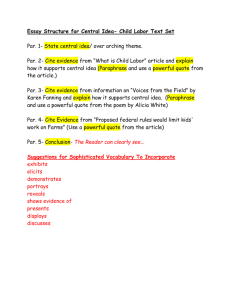

advertisement

CONCURRING OPINION OF JUDGE A. A. CANÇADO TRINDADE 1. I am voting in favor of adoption of these provisional measures through which the Inter-American Court of Human Rights is ordering that protection be extended to all the inmates at the Urso Branco Prison in Brazil. Still, I feel obliged to revisit the conceptual construct that I have been advocating in the Inter-American Court, which concerns obligations erga omnes of protection under the American Convention. I have no intention of repeating, in detail, everything I have thus far said on the subject, particularly in my other Concurring Opinions on the Orders for Provisional Measures adopted by the Court in the case of the Peace Community of San José de Apartadó (of June 18, 2002), the Communities of the Jiguamiandó and of the Curbaradó (of March 6, 2003), the Kankuamo Indigenous Community (of July 5, 2004) and the Indigenous Community of Sarayaku Indigenous People (July 6, 2004). Instead, I prefer to summarize some of the central points I made on the subject, with a view to effective protection of human rights in a complex situation such as that of the inmates at the Urso Branco Prison. 2. Indeed, well before these cases were brought to this Court’s attention, I had already warned of the pressing need to develop doctrine and jurisprudence on the legal regime of obligations erga omnes of protection of the rights of the human being ((for example, in my Concurring Opinions in Blake vs. Guatemala, Judgment on the Merits, January 24, 1998, par. 28, and Judgment on Reparations, January 22, 1999, par. 40). In my Concurring Opinion in the Las Palmeras vs. Colombia case, Judgment on Preliminary Objections, February 4, 2000, I suggested that a proper understanding of the broad scope of the general obligation to ensure the rights recognized in the American Convention, provided for in Article 1(1) thereof, could be instrumental in developing the obligations erga omnes of protection (paragraphs 2 and 6-7). 3. The general obligation to ensure –I added in my Concurring Opinion in the Las Palmeras case- is incumbent upon each State Party individually and on all of them collectively (obligation erga omnes partes - pars. 11-12). I wrote that "there could hardly be better examples of mechanism for application of the obligations erga omnes of protection (…) than the methods of supervision foreseen in the human rights treaties themselves (...) for the exercise of the collective guarantee of the protected rights. (...) the mechanisms for application of the obligations erga omnes partes of protection already exist, and what is urgently need is to develop their legal regime, with special attention to the positive obligations and the juridical consequences of the violations of such obligations. (par. 14). 4. The general obligation to ensure includes the application of provisional measures of protection under the American Convention. In my concurring opinion in the case of the Haitians and Dominicans of Haitian Origin in the Dominican Republic (Order of August 18, 2000), I took the liberty of pointing out the change that had occurred in both the rationale and object of provisional measures of protection (which historically moved from civil procedural law to public international law), resulting from the impact of their application within the framework of the International Law of Human Rights (paragraphs 17 and 23): with their introduction into the conceptual universe of the International Law of Human Rights, provisional measures undergo a transition where, rather than safeguarding the efficacy of the functions of courts, they protect the most fundamental rights of the human person. 2 With the transition from civil procedural law into international human rights law, they move out of the strictly precautionary realm and into the sphere of protection. 1 5. The jurisprudence of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights has made a decisive contribution to this subject, perhaps more than any other international tribunal to date. Its jurisprudence on the subject traces its roots to a convention and, in terms of the breadth of its scope, is unparalleled in contemporary international jurisprudence. In recent years, and right up to the present, it has tapped all the potential for protection –through prevention- that can be drawn from the language of Article 63(2) of the American Convention. 6. In my Concurring Opinion in the Matter of the Peace Community of San José de Apartadó (Order of June 18, 2002), I pointed out that the State’s obligation to protect is not confined to the State’s relations to persons under its jurisdiction; in certain circumstances that obligation also applies to relations between third parties; it is, then, a genuine obligation erga omnes of protection, which in the instant case is an obligation vis-à-vis all persons incarcerated in Urso Branco Prison. As I wrote in that Concurring Opinion –and do so in relation to the present case as well -- in the final analysis what we have here is the State’s obligation erga omnes to protect all persons subject to its jurisdiction, an obligation that becomes all the more important in a situation of constant violence and insecurity like the one at Urso Branco Prison and that "(...) requires clearly the recognition of the effects of the American Convention vis-à-vis third parties (the Drittwirkung), without which the conventional obligations of protection would be reduced to little more than a dead letter. The reasoning as from the thesis of the objective responsibility of the State is, in my view, ineluctable, particularly in a case of provisional measures of protection as the present. The intention here is to avoid irreparable harm to the members of a community and to the persons who render services to this latter, in a situation of extreme gravity and urgency, which encompasses actions, armed and otherwise, of paramilitary and clandestine groups, along with the actions of organs and agents of the public forces. (paragraphs 14-15). 7. Later, in my Concurring Opinion in the case of the Communities of the Jiguamiandó and of the Curbaradó (Order of March 6, 2003), a case that also involved individual and collective dimensions, I took the liberty of once again insisting that the response to acts of violence committed by armed irregulars of any kind must be recognition of the third-party effects of the American Convention “(the Drittwirkung),” – inherent in obligations erga omnes, - "without which the conventional obligations of protection would be reduced to little more than a dead letter.” (pars. 2-3). I added that given the circumstances of that case –and of the present case as well- it is clear that the protection of human rights determined by the American Convention, to be effective, comprises not only the relations between the individuals and the public power, but also their relations with third parties (…). This reveals the new dimensions of the international protection of human rights, as well as the great potential of the existing mechanisms of protection, - such as that of the American Convention, - set in motion in . For a study of this evolution, cf. A.A. Cançado Trindade, Tratado de Direito Internacional dos Direitos Humanos, vol. III, Porto Alegre, S.A. Fabris Ed., 2003, pp. 80-83; A.A. Cançado Trindade, "Provisional Measures of Protection in the Evolving Case-Law of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (1987-2001)", in El Derecho Internacional en los Albores del Siglo XXI - Homenaje al Prof. J.M. Castro-Rial Canosa (ed. F.M. Mariño Menéndez), Madrid, Ed. Trotta, 2002, pp. 61-74; A.A. Cançado Trindade, "Les mesures provisoires de protection dans la jurisprudence de la Cour Interaméricaine des Droits de l'Homme", 4 Revista do Instituto Brasileiro de Direitos Humanos (2003) pp. 13-25. 1 3 order to protect collectively the members of a whole community, 2 even though the basis of action is the breach - or the probability or imminence of breach - of individual rights. (par. 4). 8. As for the broad scope of the obligations erga omes of protection, in my Concurring Opinion in the Inter-American Court’s Advisory Opinion OC-18 on the Juridical Condition and Rights of Undocumented Migrants (of September 17, 2003), I noted that the jus cogens (from whence the obligations erga omnes emanate)3 characterizes them as being objective of necessity. They thus encompass all the parties for whom the legal norms were intended (omnes), whether they be members of public organs of the State or private persons (par. 76). I went on to write the following: (...) In a vertical dimension, the obligations erga omnes of protection bind both the organs and agents of (State) public power, and the individuals themselves (in the inter-individual relations). (...) as to the vertical dimension, the general obligation, set forth in Article 1(1) of the American Convention, to respect and to ensure respect for the free exercise of the rights protected by it, generates effects erga omnes, encompassing the relations of the individual both with the public (State) power as well as with other individuals (particuliers).4 (pars. 77-78). 9. Thus, given the circumstances of the present Matter of the Urso Branco Prison, as narrated in the Court’s order, the State cannot disclaim responsibility for the human rights violations (the rights to life and to humane treatment) that occurred in that prison merely because the acts of violence that resulted in those violations were committed by some inmates at the prison against other inmates. The State’s responsibility is immediately engaged, from the moment those violations occurred,5 regardless of pending legislative reforms or administrative measures (some of which have been pending for a long time). The State has an ineluctable duty of protection erga omnes, even in relations between individuals, inasmuch as victims and perpetrators alike were in the State’s custody. 10. It is true that throughout the public hearing this Court held on June 28, 2004, the parties demonstrated a spirit of procedural cooperation, which this Court has viewed in a positive light. Nevertheless, the answers given to the various questions that I asked of the parties (the petitioners seeking provisional measures, the InterAmerican Commission and the Brazilian State) during that hearing made it clear that the situation at the Urso Branco Prison is still one of extreme gravity and urgency, in 2 . Suggesting an affinity with the class actions. . In this same Opinion I wrote the following: “By definition, all the norms of jus cogens generate necessarily obligations erga omnes. While jus cogens is a concept of material law, the obligations erga omnes refer to the structure of their performance on the part of all the entities and all the individuals bound by them. In their turn, not all the obligations erga omnes necessarily refer to norms of jus cogens.” (par. 80). 3 4 . Cf., in this respect, in general, the resolution adopted by the Institut de Droit International (I.D.I.) at the 1989 Santiago de Compostela session (Article 1), in: I.D.I., 63 Annuaire de l'Institut de Droit International (1989)-II, pp. 286 and 288-289. 5 . Concerning the finding that the State’s international responsibility was engaged, cf. my opinion (which I presented to this Court today) in the case of the Gómez Paquiyauri Brothers vs. Peru (Judgment of July 8, 2004), paragraphs 11-18. And for a study on this subject, cf. A.A. Cançado Trindade, "A Determinação do Surgimento da Responsabilidade Internacional dos Estados", 26 Revista da Faculdade de Direito da Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais - Belo Horizonte (1978) pp. 158-199; A.A. Cançado Trindade, O Direito Internacional em um Mundo em Transformação, Rio de Janeiro, Ed. Renovar, 2002, pp. 371-408. 4 the language of Article 63(2) of the American Convention. Hence the Inter-American Court’s adoption of these provisional measures. 11. In effect, in this Order of July 7, 2004, the Court has expressed its “concern” over the fact that "(…) while these provisional measures were in effect, more people have died at the Urso Branco Prison, even though the fundamental purpose to be served with adoption of these measures is to effectively protect the lives and personal safety of all persons incarcerated in the prison and those who enter it. (...)Although the prison riot was brought to an end in late April 2004, the InterAmerican Commission, the petitioners and the State all agree that the situation at the prison is unacceptable. (...) (...)The information recently provided by the Inter-American Commission, the petitioners and the State, and their statements during the public hearing held on June 28, 2004, demonstrate that the prevailing situation at Urso Branco Prison is one of extreme gravity and urgency (...). (...) Given the gravity of the situation at the Urso Branco Prison, the State must immediately adopt all measures necessary to ensure that the rights to life and to the integrity of one’s person are preserve, independently of whatever other measures are gradually adopted in the area of prison policy. (...) (...)The State must adopt forthwith the measures necessary to ensure that no one in the Urso Branco Prison is either killed or injured.(...)6 12. It seems self-evident to me that the fundamental principle of respect for human dignity applies to all human beings, no matter what their circumstance. That includes those deprived of their liberty. This is the direction that the international jurisprudence on the subject of human rights protection has taken. Indeed, the jurisprudence constante of the Inter-American Court has been to remind the State that because it is in charge of prison institutions, it is the guarantor of the rights of the detainees who are in its custody.7 13. The Inter-American Court has held that “every person deprived of her or his liberty has the right to live in detention conditions compatible with her or his personal dignity, and the State must guarantee to that person the right to life and to humane treatment."8 That being the case, the Court added, the State’s “power is not unlimited, as it has the duty, at all times, of applying procedures that are in accordance with the Law and that respect the fundamental rights of all individuals under its jurisdiction (...) [I]f a person was detained in good health conditions and subsequently died, the State has the obligation to provide (…) information and evidence pertaining to what happened to the detainee."9 14. The European Court of Human Rights has followed the same line of reasoning, having repeatedly held that “Detained persons are in a vulnerable position and the 6 . Considering 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12 of the present Order. 7 . Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR), Case of Bulacio v. Argentina, Judgment of September 18, 2003, Series C, No.100, pars. 126-127 and 138); IACtHR, Case of Hilaire, Constantine and Benjamin et al. v. Trinidad and Tobago, Judgment of June 21, 2002, Series C, No. 94, par. 165; IACtHR, Case of Bámaca Velásquez v. Guatemala, Judgment of November 25, 2000, Series C, No. 70, par. 171; Case of Neira Alegría et al. v. Peru, Judgment of January 1, 1995, Series C, No.20, par. 60. . 195. 8 IACHR, Case of Castillo Petruzzi et al. v. Peru, Judgment of May 30, 1999, Series C, No. 52, par. . IACtHR, Case of Juan Humberto Sánchez v. Honduras, Judgment of June 7, 2003, Series C, No. 99, pars. 86 and 111. 9 5 authorities are under a duty to protect them.” 10 Concerning persons in custody, time and time again the European Court has made the point that "it is incumbent on the State to account for any injuries suffered in custody, which obligation is particularly stringent where that individual dies."11 The Court has also held that "there should be some form of effective official investigation when individuals have been killed as a result of the use of force." 12 The State’s due diligence obligation also covers relations between or among individuals, as the European Court held in Osman v. United Kingdom (1998), by noting that in certain circumstances it may well imply a "positive obligation on the authorities to take preventive operational measures to protect an individual whose life is at risk from the criminal acts of another individual."13 15. In the present Matter of Urso Branco Prison, the State cannot disclaim international responsibility for human rights violations (the inmates’ rights to life and to humane treatment) for reasons of internal order having to do with its federal structure. In its August 27, 1998 judgment on reparations in the Case of Garrido and Baigorria v. Argentina, the Inter-American Court invoked “case law, which has stood unchanged for more than a century,” which holds that “a State cannot plead its federal structure to avoid complying with an international obligation” (par. 46). And its famous Advisory Opinion OC-16 (October 1, 1999) on The Right to Information on Consular Assistance. In the Framework of the Guarantees of the Due Process of Law, - a truly groundbreaking and historic decision that has been a source of inspiration to international jurisprudence in statu nascendi on the subject- the Inter-American Court held, on this very point, that States must comply with their obligations under conventions, "regardless of whether theirs is a federal or unitary structure." (par. 140 and operative paragraph 8). 16. In short, as the above-cited case law illustrates, no matter what the circumstance, the State has a due diligence obligation to prevent irreparable harm to persons under its jurisdiction and in its custody. Provisional measures of protection such as those that the Inter-American Court just adopted in the present Order on the Matter of Urso Branco Prison, serve to establish continual monitoring of a situation of extreme gravity and urgency, based on a provision of a human rights treaty like the American Convention (Article 63(2)). As I had already anticipated in my Concurring Opinion in the Matter of The Communities of the Jiguamiandó and Curbaradó (pars. 6-8), such measures also contribute to the gradual establishment of a genuine right to humanitarian assistance. . Cf., inter alia, European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), Orhan v. Turkey, Judgment of June 18, 2002, Series A, No. 3645, par. 326; and ECtHR, Case of Aksoy v. Turkey, Judgment of November 26, 1996, paragraph 61; ECtHR, Case of Anguelova v. Bulgaria, Judgment of May 23, 2002, par. 110. 10 . ECtHR, Case of Paul and Audrey Edwards v. United Kingdom, Judgment of March 14, 2002, Series A, No. 3449, par. 56; ECtHR, Case of Avsar v. Turkey, Judgment of July 10, 2001, Series A, No. 2637, par. 391; ECtHR, Case of Keenan v. United Kingdom, Judgment of April 3, 2001, Series A, No. 2421, par. 91. 11 12 . ECtHR, Case of Cakici v. Turkey, Judgment of July 8, 1999, Series A, No. 1090, par. 86. . ECtHR, Case of Osman v. United Kingdom, Judgment of October 28, 1998, Series A, No. 1050, par. 115. 13 6 17. They illustrate that in situations of this kind, it is possible and viable to act strictly within the framework of the Law, 14 thereby reaffirming the primacy of the law over the indiscriminate use of force. They testify to the current process of humanization of international law (moving toward a new jus gentium) in the area of provisional measures of protection as well. All this points up the fact that the human conscience (the ultimate source of all Law) has awakened to the need to protect the human person from violations of his rights by both the State and third parties. 18. At the Institut de Droit International, I have maintained that in the exercise of the emerging right to humanitarian assistance, the emphasis must be on the persons of the beneficiaries of the humanitarian assistance, and not on the potential for action of the agents materially trained to provide that humanitarian assistance. The ultimate basis for the exercise of that right lies in the inherent dignity of the human person: human beings are, in effect, the titulaires of the protected rights and of the right to humanitarian assistance. Their defenselessness and suffering (in prison) – especially in situations of poverty, economic exploitation, social marginalization and perhaps brutalization-merely underscore the need for obligations erga omnes to protect the rights that are inherent in the human person. 19. As I see it, those obligations erga omnes must be developed and complied with in order to put an end to violence within prisons, impunity and institutionalized injustice. Moreover, the titulaires of the protected rights (or their legal representatives) are those best qualified to identify their basic humanitarian relief needs, which constitutes a response, informed by the Law, to the new needs for human protection. If the human person’s international legal personality and standing ultimately materialize, then the right to humanitarian assistance may gradually become justiciable.15 20. Furthermore, as recent cases before this Court involving members of human collectivities have made clear, the current expansion of international juridical personality and standing16 is a response to a pressing need of the international community in our times. The development of the doctrine and jurisprudence on obligations erga omnes of protection of the human person, in any and all situations or circumstances, will certainly be a contribution toward the formation of a true international ordre public based on respect for and observance of human rights, capable of ensuring greater cohesiveness in the organized international community (the civitas maxima gentium), centered around the human person as the subject of international law. Antônio Augusto Cançado Trindade Judge Pablo Saavedra-Alessandri Secretary . Without having to resort to the unconvincing and unfounded rhetoric of so-called “humanitarian intervention.” 14 . Cf. A.A. Cançado Trindade, "Reply [- Assistance Humanitaire]", 70 Annuaire de l'Institut de Droit International - Session de Bruges (2002-2003) n. 1, pp. 536-540. 15 . Cf. A.A. Cançado Trindade, El Acceso Directo del Individuo a los Tribunales Internacionales de Derechos Humanos, Bilbao, Universidad de Deusto, 2001, pp. 9-104. 16