View as DOC

'Disparate Impact' May Result in Less Than It Appears

Sid Steinberg

The Legal Intelligencer

04-13-2005

In Smith v. City of Jackson, the U.S. Supreme Court made it possible for plaintiffs to win a claim for age discrimination where an otherwise neutral policy disproportionately hurts older workers.

In finding that so-called "disparate impact" claims are viable under the Age Discrimination in

Employment Act (as they have been under Title VII for over 30 years), the Court held that plaintiffs may be able to prevail in such cases even without proving intentional age discrimination. While some commentators (and even a colleague or two) have suggested that Smith will be a major new plaintiff weapon in age discrimination cases, there may, in fact, be less to the decision than it initially appears.

PAY PLAN

In the case, a group of police officers and public safety dispatchers in Jackson, Miss., alleged that the city's newly implemented pay plan was discriminatory because it had the effect of giving younger workers larger pay raises than older workers. There was no mention of age in the plan, which was implemented in 1998 and revised the next year.

Instead, raises were based on the age-neutral considerations of seniority and rank

(awarding a larger annual percentage increase to employees with five years' or less seniority).

The plaintiffs argued that the city should be held liable for age discrimination because its pay plan resulted in a "disparate impact" on older workers. The district court and 5th U.S.

Circuit Court of Appeals found that disparate impact claims were not viable under the ADEA.

The 5th Circuit decision was consistent with those of four other circuits, while three appellate courts had found the ADEA supported disparate impact claims.

The 3rd Circuit had never addressed this issue directly, although it suggested strongly in

Dibiase v. SmithKline Beecham Corp. that disparate impact claims could not be brought under the ADEA.

In very broad terms, discrimination claims can be classified under "disparate treatment" or

"disparate impact" headings. Disparate treatment claims depend upon evidence that an employer treated one individual or group of individuals differently than another group and consideration of the protected category (age, race, sex, disability, etc.) played a role in the decision. Disparate impact claims, on the other hand, look to whether an otherwise neutral policy adversely impacts a set of employees in one protected category. Evidence of discriminatory motivation is not at issue.

The Supreme Court granted certiorari to resolve the circuit split. Without Chief Justice

William H. Rehnquist participating in the decision, a 5-3 majority recognized the viability of

disparate impact claims under the ADEA. There was unanimity, however, that the circuit court's decision in favor of the city of Jackson should be affirmed.

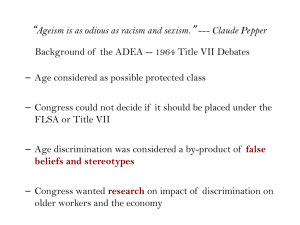

In finding that the ADEA, like Title VII, supports disparate impact claims, the court looked to the similarity in language between the two statutes and found that the reasoning of the court in Griggs v. Duke Power Co. -- finding disparate impact claims viable under Title VII -- applied to the ADEA.

The court found, however, a crucial difference between the language of Title VII and the

ADEA, which weakens any disparate impact claim. The ADEA contains what is sometimes referred to as "RFOA provision." RFOA stands for "reasonable factors other than age," and the statute provides that it is not unlawful for an employer to make a differentiation between employees where "it is based on reasonable factors other than age discrimination."

The court observed, therefore, that "in cases involving disparate-impact claims, [the RFOA provision precludes] liability if the adverse impact was attributable to a nonage factor that was 'reasonable.'" This led to the conclusion that "the scope of disparate-impact liability under ADEA is narrower than under Title VII."

In applying the RFOA to the facts of the case, the court found that plaintiffs had failed to identify the specific practice being challenged, as opposed to just pointing out that the pay plan at issue was relatively less generous to older workers. By failing to point to the practice being challenged, the plaintiffs ignored the "myriad of innocent causes that may lead to statistical imbalances." Moreover, the court found that the city's reliance on seniority and rank were "unquestionably reasonable."

For Supreme Court observers, the lineup of the justices was intriguing. Justice Antonin

Scalia concurred in the finding that the ADEA supports disparate impact claims on the grounds that the EEOC's regulations were entitled to deference on this issue. He joined

Justices John Paul Stevens, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen G. Breyer and David H. Souter in the decision and engaged in a rather caustic footnote exchange with Justice Sandra Day

O'Connor (who was joined by Justices Clarence Thomas and Anthony M. Kennedy), at one point saying that her dissent "makes little sense."

QUESTIONABLE EFFECT

As a practical matter, while disparate impact opens a new avenue for claims under the

ADEA, it is unlikely to have a significant effect on the vast majority of cases. Initially, of course, most cases are individual claims of age discrimination, asserting that a particular employee was treated worse than a younger member of the work force. While courts have recognized that individuals may bring disparate impact claims, such claims are far more complicated and expensive than the average age plaintiff will need to establish his or her case. Furthermore, where individuals are involved, the case will more likely be brought as a

"pattern and practice" claim.

While disparate impact is a type of "no-fault" theory (not requiring evidence of motivation), the plaintiff will need to establish that she or he was impacted by an otherwise neutral policy that disproportionately harms both the plaintiff and other employees over 40 and, under the RFOA provision, that the particular practice at issue was "unreasonable."

The more significant impact will be for class action litigation under the ADEA, where otherwise neutral policies will now be scrutinized for their effect and not just for their

motivation. Again, though, success under this theory will require a far more compelling scenario than presented by the City of Jackson plaintiffs.