Microsoft Operations Framework

White Paper

Published: December 2000 version 1.0

For information on Microsoft Operations Framework, see

http://www.microsoft.com/business/services/mcsmof.asp

Risk Model for Operations

Contents

Abstract .....................................................................................................................3

Introduction ...............................................................................................................3

Why Operations Needs Risk Management ...............................................................4

Overview of the Risk Model for Operations .............................................................8

The Five Steps of Risk Management ......................................................................14

Relating the Risk Model to MOF ............................................................................26

Comparing the Risk Model for Operations to Other Risk Models ..........................31

Examples .................................................................................................................33

Conclusion...............................................................................................................37

Additional Information ............................................................................................37

Appendix A: Glossary .............................................................................................39

Appendix B: Detailed Examples .............................................................................42

2000 Microsoft Corporation. All rights reserved.

The information contained in this document represents the current view of Microsoft Corporation on the

issues discussed as of the date of publication. Because Microsoft must respond to changing market

conditions, it should not be interpreted to be a commitment on the part of Microsoft, and Microsoft cannot

guarantee the accuracy of any information presented after the date of publication.

This document is for informational purposes only. MICROSOFT MAKES NO WARRANTIES, EXPRESS

OR IMPLIED, IN THIS DOCUMENT.

Microsoft and Windows are either registered trademarks or trademarks of Microsoft in the United States

and/or other countries.

Risk Model for Operations

3

Abstract

This white paper is one of a series about Microsoft® Operations Framework (MOF).

For a complete list of these publications, please see the MOF Web site at

http://www.microsoft.com/mof.

This white paper is intended for all IT staff whose work involves operations and service

management. It explains why risk management is increasingly important in operations,

describes the risk model for operations, relates it to Microsoft Operations Framework,

and illustrates its applicability to real-world operations risks. An appendix details the

management of several risks, and a glossary explains key terms.

Anyone reading this paper already should have ready the Microsoft Operations

Framework “Executive Overview” white paper, which contains important background

information for this topic.

Introduction

Executive Summary

Information technology professionals who are responsible for mission-critical systems

have seen their work change in ways that make risk management increasingly

important. The business relies more on information technology (IT) than it used to,

which raises the impact of failure; the IT environment has more moving parts than it

used to, which raises the probability of problems; more people notice IT problems and

react to them, which creates additional consequences for failure; and more of the

infrastructure is outside the IT group’s direct control. At the same time, the IT group has

less time to react, and is less able to manage risk by applying tight change-control

measures. Combined, these trends mean that operations groups are facing larger

challenges with a smaller tool kit. The risk model for operations helps expand the tool

kit.

This white paper explains the core principles and components of the risk model for

operations. It is intended for operations staff at all levels, as well as Microsoft

Consulting Services and partner consultants. The model is applicable in nearly all

organizations, and the examples illustrate situations commonly found at service

providers, “dot-coms” and “e-businesses,” and IT groups of large organizations.

First, the paper makes the case that risk management is becoming more important and

more difficult. It then describes the risk model for operations: a process for managing

risks with a proactive approach that embeds risk management practices into every IT

team role and into every IT process. The paper concludes with examples that show how

the model can be applied to real-world operations risks.

4

Risk Model for Operations

Why Operations Needs Risk Management

Greater Risk of IT Failure

A risk is the possibility of suffering a loss, and risk management is essentially the

process of identifying risks and deciding what to do about them. Risk management is

increasingly important to IT in general, and to operations groups in particular, because

business is more able to suffer losses due to IT decisions.

Both the number and the severity of potential IT failures (specifically the ones related to

IT operations) are rising over time:

Business transactions are increasingly dependent on IT, so failures in IT are more

likely to impact the business, and that impact is more likely to be severe.

The IT environment is increasingly complex, so even if the environment stays the

same size, the number of potential failure points is rising.

IT directly controls less of the infrastructure, so managing the possibility of failure is

more important because IT has less ability to react after the failure occurs.

When an IT failure occurs, there is less time between the failure and its impact on

the business.

IT failures are increasingly visible outside the data center, so more people react

negatively when a failure occurs.

In short, IT today has more potential to enable business than ever before, but failures in

IT have more potential to disable business.

At the same time, the traditional risk management strategy of tight change control is less

often available, and less often effective.

As a result, operations needs a larger set of risk management tools.

The next sections provide a closer examination of trends in IT failure.

Risk Model for Operations

5

Business Is More Dependent on IT

Today, more of the systems that IT manages are critical to the business. For example, 10

years ago many companies’ communications were based on non-IT services such as

paper memos, an internal mailroom service, an external postal service, and the

telephone. Today, IT is responsible for communication hubs such as e-mail service,

intranets, and Internet sites: systems that were not considered business-critical a decade

ago. Companies involved in e-commerce are at even greater risk from IT failures,

because those businesses’ core processes (such as value chain, supply chain, businessto-customer, business-to-business, and business-to-employee) now rely on IT for their

success.

Because business is increasingly dependent on IT services, those services are

increasingly a source of risk to the business: Failures in the IT group are more able to

cause failure in the business as a whole.

The Environment Is More Complex

Simply put, the IT environment includes more “moving parts” today than it did in the

past. There are more desktops, more servers, more connections, more systems

integration, and more end-to-end services. This is partly due to the move from

centralized computing, to client/server computing, to the vision of Microsoft .NET, in

which all objects are distributed. As that progression takes place, the number of items in

the infrastructure increases even if the scope of the infrastructure stays the same.

The diversity of the infrastructure has also increased. For example, IT groups that used

to worry about the links between the terminals and a handful of hosts now keep track of

local area networks (LANs) and wide area networks (WANs); land lines and dial-up

access and wireless links; internal networks as well as connections to the Internet. Client

systems are another example—in the past IT dealt with terminals, but today the client

hardware could range from desktops and laptops, to handheld computers, to wireless

information appliances, to Internet-enabled phones and pagers.

The number of users is also increasing. In the early days, a few operators interacted with

a mainframe, then later the pool of users grew to include a few dozen clerks, then a few

hundred knowledge workers on the mainframe and on personal computers. Today, even

more customers reach e-commerce sites from their home systems. In addition to the

number of users, their autonomy is increasing as well. Mainframe users didn’t upgrade

software on their own, but home users do this all the time.

Because the environment is more complex and diverse, the IT group is more able to fail

the business than it was in the past.

6

Risk Model for Operations

Traditional IT Directly Controls Less of the Infrastructure

More of the systems that are part of IT services are managed outside of the company.

For example, a retailer that receives orders on its Web site might rely on other

companies’ systems for credit verification, warehousing, and shipping.

The “virtual IT environment” does not necessarily increase the potential for failure, and

in fact it can decrease risk by outsourcing a service to specialists who are best able to

operate it and most able to prevent it from failing. This trend is important for risk

management because the customer may still expect the company to provide the end-toend service.

In other words, a virtual IT environment can reduce a company’s control over the entire

infrastructure without reducing the company’s responsibility for keeping the

infrastructure running.

Less Time Between Failure and Impact

If a service fails, there is a window of time during which the IT group can attempt to

recover the service before the failure impacts the business. If a system that prints

customers’ bills were to fail, that window might be hours or days in length because

there is often a three-week delay between printing a bill and expecting to receive the

customer’s payment. If IT can recover the service within that time then the customers

receive bills on time, or close enough that most won’t notice the delay, and the

company’s revenue stream won’t be interrupted. However, an e-commerce site’s

customers may expect transactions to complete within one minute, and expect e-mail

confirmation of each transaction within another five minutes.

In the past, the strategy of “fix-on-fail” was more feasible because there was time to

make the fix, and that’s less often true today.

Failure Is More Visible

Years ago, IT managers might have wondered, “If a service fails in the data center and

no one notices, is it a crisis?” That question has become irrelevant to many IT

organizations because so many more failures are immediately noticeable outside the

data center. Five years ago, if your company’s Web site was unavailable for an hour, the

few people who noticed were your own IT staff. Today, the list of people who would

notice that failure might include hundreds of customers, a dozen competitors, and every

analyst who tracks your company’s stock.

Visibility is important because people not only notice failures, they also react. A case in

point is a well-publicized day-long service outage suffered by an online auction site.

Customers noticed it; to satisfy them, the site’s parent company refunded all the fees it

collected for every auction in progress, a sum reportedly equal to one-third of the

company’s quarterly profits. Analysts and investors noticed the problem, too—the

company lost 25 percent of its market capitalization in two days.

The first four trends make failure more likely and more severe; the visibility of missioncritical systems outside the company amplifies the severity of failure.

Risk Model for Operations

7

Traditional Techniques Less Useful

The trends above make IT failure a greater risk to the business. At the same time, some

traditional risk management tools are less often applicable.

IT operations staff traditionally managed risks to the production infrastructure by using

change management practices. Changes to the infrastructure were either denied or they

were managed with a strict process and a long timeline. This ensured stability, but

reduced organizational flexibility.

Today, the business environment is changing more rapidly, and the business can adapt

only as quickly as its systems. Business management is more likely to tell IT what to

implement, rather than ask, so IT can less often manage risk by denying the change

requests. An IT group that used to reduce risk through six-week change cycles now

might find itself forced to make changes in six days, six hours, or even less.

Even if business management doesn’t limit the effectiveness of change control, the IT

technology can. For example:

In the past an IT group could limit risk by announcing that no changes to the

network infrastructure would be permitted for the next 30 days. That edict can’t be

enforced when the Internet is a part of the network.

In the past an IT group could limit risk by standardizing the hardware and software

of all order entry systems. That’s not an option when customers use their own

computers to order goods from a Web site.

Implications

Over time, environmental complexity increases the probability of failures, dependence

on IT increases the impact of those that occur, and increased visibility amplifies that

impact. As the number and impact of potential failures are rising, IT directly controls

less of the infrastructure, has less time to react, and is less able to apply traditional risk

management methods to deal with the possibility of failure. What’s an IT manager to

do?

Microsoft Operations Framework recommends that operations should integrate risk

management into decision-making the way it has already integrated other critical factors

such as time, money, and labor:

Risk management should be integrated into operations decision making in every job

function and every role.

Risk management should be taken seriously and given an appropriate amount of

effort.

Risk management should be done continuously to ensure that operations is dealing

with the risks that are relevant today, not just the ones that were relevant last quarter.

Fortunately, formalizing risk management practices is an achievable goal. Risk

management is a well-understood discipline, and it is readily applicable to IT

operations, as described in the next section.

8

Risk Model for Operations

Overview of the Risk Model for Operations

Benefits

The risk model for operations applies proven risk management techniques to the

problems that operations staff face every day. There are many models, frameworks, and

processes for managing risks. They’re all about planning for an uncertain future, and the

risk model for operations is no exception. However, it offers greater value than many

others through its key principles, a customized terminology, a structured and repeatable

five-step process, and integration into a larger operations framework. All of these are

elements are detailed below.

Origin of the Model

The risk model for operations was developed in response to customer requests for a

framework to help organizations that run their businesses on the Microsoft platform to

manage risk while operating and managing those services. Microsoft Solutions

Framework (MSF) defined a widely applicable risk model whose description is

customized to address risk management during projects, especially software

development and deployment projects. The risk model for operations is based on the

MSF risk model, with extensions and customizations to address the needs of operations

groups.

Characteristics of Risk

Risk has some basic aspects that most people don’t understand or don’t think about, and

a risk management model has to acknowledge them to be successful. Some aspects are

as follows:

Risk is a fundamental part of operations. The only environment that has no risk is

one whose future has no uncertainty: no question of whether or when a particular

hard disk will fail; no question of whether a Web site’s usage will spike or when or

how much; no question of whether or when illness will leave the help desk shortstaffed. Such an environment does not exist.

Risk is neither good nor bad. A risk is the possibility of a future loss, and although

the loss itself may be seen as “bad,” the risk as a whole is not. It may help to realize

that an opportunity is the possibility of a future gain. There is no risk without

opportunity, and no opportunity without risk.

Risk is not something to fear, but something to manage. Because risk is not bad,

it is not something to avoid. Operations teams deal with risks by recognizing and

minimizing uncertainty and by proactively addressing each identified risk. If a loss

is one possible future outcome, then the other possible outcomes are gains, smaller

losses, or larger losses. Risk management lets the team change the situation to favor

one outcome over the others.

Risk Model for Operations

9

Principles of Successful Risk Management

The risk model for operations advocates these principles:

Assess risks continuously. This means the team never stops searching for new

risks, and it means that existing risks are periodically reevaluated. If either part does

not happen, risk management will not benefit the company.

Integrate risk management into every role and every function. At a high level,

this means that every IT role shares part of the responsibility for managing risk, and

every IT process is designed with risk management in mind. At a more concrete

level, it means that every process owner:

Identifies potential sources of risk.

Assesses the probability of the risk occurring.

Plans to minimize the probability.

Understands the potential impact.

Plans to minimize the impact.

Identifies indicators that show the risk is imminent.

Plans how to react if the risk occurs.

For example, the support manager with overall responsibility for the help desk

function will perform all of these tasks to manage the risks that are most

important for the help desk. Other people in that manager’s extended team may

perform a subset of those tasks: Everyone will help identify new risks, but

perhaps only one or two people will be responsible for estimating probability or

making plans to minimize impact.

Treat risk identification positively. For risk management to succeed, team

members must be willing to identify risk without fear of retribution or criticism. The

identification of a risk means the team faces one less unpleasant surprise. Until a

risk is identified, the team cannot prepare for it.

Use risk-based scheduling. Maintaining an environment often means making

changes in a sequence, and where possible the team should make the riskiest

changes first. An example is beta-testing an application. If the company wants 10

features to work, and two of them are so important that the lack of either would

prevent the application’s adoption, test those two first. If they were to be tested last

and either was to fail, then the team would have lost the resources invested in testing

the first eight.

Establish an acceptable level of formality. Success requires a process that the team

understands and uses. This is a balancing act. If the process has too little structure,

people may use it but the outputs won’t be useful; if it is too prescriptive, people

probably won’t use it at all.

These principles are summarized in the word proactive. A team that practices

proactive risk management acknowledges that risk is a normal part of operations,

and instead of fearing it the team views it as an opportunity to safeguard the

future. Team members demonstrate a proactive mindset by adopting a visible,

measurable, repeatable, continuous process through which they objectively evaluate

risks and opportunities, and take action that addresses risks’ causes as well as

symptoms.

10

Risk Model for Operations

Process Overview

When operations teams use proactive risk management, they assess risks continuously

and use them for decision making. The team carries the risks forward and deals with

them until they are no longer important, or until they occur and become known

problems.

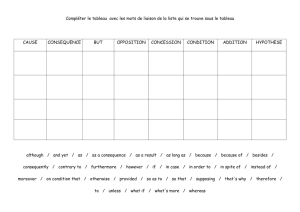

The following diagram illustrates the five steps of the risk management process:

identify, analyze, plan, track, and control. It is important to understand that each risk

goes through all of these steps at least once, and often cycles through numerous times.

Also, each risk has its own timeline, so multiple risks might be in each step at any point

in time.

Later sections will detail these steps.

1

2

Identify

Retired

Risk

List

5

Analyze

Risk

Assessment

Document

Control

3

Top

n

Risks

4

Track

Figure 1 - The proactive risk management process

Plan

Risk Model for Operations

11

Risk Lists

The simplest view of the process is that the five steps feed information into and out of

three lists of risks: the master risk list, the top risks list, and the retired risk list.

Understanding the three lists makes the five steps easier to learn.

The Master Risk List

Figure 2

During each step in the process, the team gathers information about a particular risk and

adds that information into the master risk list. Each subsequent step builds on the

previous ones by adding more elements of the risk, or it draws on the current elements

to support decision making. For example, the analyzing step initially adds information

about the risk’s impact and probability. The process is cyclic, so future passes through

the analyzing step may review and revise those impact and probability estimates.

The master risk list is technology-independent. It could be as crude as a set of index

cards, though that would make certain functions (such as sorting and linking) very

labor-intensive. The list can be implemented simply as a Microsoft® Word document or

a Microsoft® Excel spreadsheet, or it can be as complex as a multitiered database

application.

Note that the size of the master risk list is more an indicator of the team’s thoroughness

than an indicator of the IT group’s health or stability.

Top Risks List

Figure 3

12

Risk Model for Operations

Managing risk takes time and effort away from daily operations activities, so it is

important for the team to balance the overhead of risk management against the expected

savings. This usually means identifying a small number of major risks that are most

deserving of the team’s limited time and resources.

One way to think of this is that the master risk list is prioritized, and the risks at the top,

the ones that are important enough to be actively managed, make up a separate top risks

list. The size of this list will vary between IT groups, and within one IT group it is likely

to vary over time.

Retired Risk List

Figure 4

The master risk list holds all the risks that the team has identified, whether they’re

important enough to appear on the top risks list or not. Some of those risks never go

away, such as those related to natural disasters. Others reach a point where they’re no

longer relevant. For example, the team might reduce the probability of the risk to zero.

Or, the source of the risk may leave the environment. Risks specific to an outdated

software application are no longer relevant after that application has been completely

phased out.

Whenever a risk becomes irrelevant, it is moved from the master risk list to the retired

risk list. This list serves as a historical reference from which the team can draw in the

future. For example, if the team has previously tracked risks related to help desk

processes, and then the help desk function is outsourced to another company, some of

the help desk-related risks might be retired. If the help desk function is later brought

back in-house, the team can draw on the retired risk list for guidance. Also, people may

consult this list as a starting point for identifying new risks. Finally, if the team lowers a

risk’s probability or impact to zero, then the notes about what the team did may benefit

other people facing similar risks.

When thinking about retiring risks, it can be useful to consider risks as having multiple

instances. For example, a corporate merger introduces the risk of severe IT budget and

staff cuts. If the group survives one merger it can retire that instance of the risk, but

other instances remain because subsequent mergers might happen.

Risk Model for Operations

13

Process-wide Best Practices

These suggestions apply to all five steps of the risk model.

Adopting Risk Management

If an operations group does not already have a culture of risk management, then

adopting it can be a significant change. The biggest obstacle to that change is the

complexity of the process. People who are not yet doing risk management in a

structured way generally don’t see the need to change, and if the risk management

process is too complex then people are likely to dismiss it as unproductive busywork.

Keep this in mind when considering the best practices in this white paper. They make

risk management more effective, but some also increase the complexity.

Chief Risk Officers

A growing practice is to appoint chief risk officers (CROs) and to have a risk

management team within the IT organization that is separate from the operations teams.

In these cases, the division of responsibilities between the risk management team and

the operations team should be very clear.

At first glance, the CRO position might seem to contradict the key principle of

integrating risk management into all job roles and functions. The distinction is whether

everyone plays a part in risk management. If so, then having a specific role such as a

CRO focus on risk management full time can be very helpful, acting as a specialist and

mentor, and coordinating risk management activities that might otherwise be inefficient

or even contradictory.

Emergency Response Teams

Large organizations often have emergency response teams (ERTs) that react to critical

failures and disasters. They are trained to respond by following established emergency

response and contingency plans. These teams need to be included during all phases of

risk management, and especially contingency planning.

Human Resources and Training

Risk management is very much dependent on operations personnel. It should commence

from the day an employee is hired. Ideally, make risk-management skills a factor when

hiring people into the IT group. Give everyone access to risk management training.

Also, make sure that everyone receives proper job training. The better people

understand a job, the more effectively they will identify and address its risks.

14

Risk Model for Operations

The Five Steps of Risk Management

Step 1: Risk Identification

1

Figure 5

Risk identification is the first step in the proactive risk management process. It provides

the opportunities, cues, and information that allow the team to raise major risks before

they adversely affect operations and hence the business.

This step is closely related to the IT Infrastructure Library (ITIL) term

“classification”—formally identifying incidents, problems, and known errors by origin,

symptoms, and causes.

In this step, the team identifies the components of the risk statement:

Condition

Operations consequence

Business consequence

Source of risk

Mode of failure

Condition and Consequences

An intuitive way to discuss the future is “if-then” statements: The condition is the “if”

part of the statement, and the consequence is the “then” part. For example, “If the Web

server’s sole power supply fails, then the company’s Web site will be unavailable.”

Note that there can be a many-to-many relationship between condition and

consequence. A single condition can cause numerous consequences, as the following

table shows.

Condition

If the Web server’s sole power supply fails …

Consequences

… then the server will be unavailable.

… then the operations team will incur the cost of a

replacement power supply.

… then someone must interrupt their regular work

to install the new power supply.

Risk Model for Operations

15

Or, numerous conditions can cause the same consequence, as shown below.

Conditions

Consequence

If the Web server’s sole power supply fails …

… the server will be unavailable.

If a technician takes the server offline to install an

application patch …

If a construction crew cuts the buried cable that links

the data center to the rest of the company …

It is important to separate the consequence into two parts during identification: the

operations consequence and the business consequence. Continuing the previous

example, the operations consequences include the cost of a power supply and the labor

to install it; the business consequences might include the damage to the company’s

reputation, and lost revenue if the site was being used for e-commerce. Distinguishing

between these is critical later in the process when the team ranks risks to ensure the

most important ones get the attention they deserve, because a risk may have a high

operational consequence but a low business consequence, or vice versa.

Source of Risk

There are four main sources of risk in IT operations:

People. Everyone makes mistakes, and even if the group’s processes and technology

are flawless these human errors can put the business at risk.

Process. Flawed or badly documented processes can put the business at risk even if

they are followed perfectly.

Technology. The IT staff may perfectly follow a perfectly designed process, yet fail

the business because of problems with the hardware, software, and so on.

External. Some factors are beyond the IT group’s control but can still harm the

infrastructure in a way that fails the business. Natural events such as earthquakes

and floods fall into this category, as do externally generated, man-made problems

such as civil unrest, computer virus attacks, and changes to government regulations.

These are broad categories, and at face value they overlap. For example, if a newly

hired operator undergoes training on the backup software, and a week later makes a

mistake that causes the backup to fail, is the source of risk “people” or “process”? If the

company relies on a telecommunications company (a “telco”) for Internet access and

that telco’s hardware fails, is that “technology” or “external”?

There are many ways to decide which category a risk fits in, and it is more important to

define one way and stick to it, rather than spend time seeking a “perfect” way. One

option is to ask whether the IT group has any control over the risk’s cause. If not, the

source is external. This would define a telco’s hardware problem as “external.” For the

other three sources, would the problem have occurred if the person had been different,

or if the process had been different, or if the technology had been different? This would

define the operator’s failure as “people” if the operator didn’t pay attention during

training or forgot what the lesson, or as “process” if the training was incomplete or

badly designed.

Why worry about the source of risk? Because it will affect the way the team manages

the risk in later steps of the process. For example, the team will deal with the possibility

of inattentive trainees differently than the possibility of poor-quality training materials.

16

Risk Model for Operations

Mode of Failure

There are four main ways in which operations can fail the business:

Cost. The infrastructure can work properly, but at too high a cost, causing too little

return on investment.

Agility. The infrastructure can work properly, but be unable to change quickly

enough to meet the business needs. Capacity problems are the most obvious case.

For example, someone might have a dozen new servers ready to support increased

processing needs, but forget that the cooling systems in the data center were already

at peak capacity, and upgrading those systems will take a month.

Performance. The infrastructure can fail to meet users’ expectations, either because

the expectations were set wrong, or because the infrastructure performs incorrectly.

Security. The infrastructure can fail the business by not providing enough protection

for data and resources, or by enforcing so much security that legitimate users can’t

access data and resources.

Best Practices

These best practices will be beneficial during the risk identification step.

Continual Identification

When a group adopts risk management, the first step is often a brainstorming session to

identify risks. Identification does not end with that meeting. Identification happens as

often as changes are able to impact the IT infrastructure—which is to say, it happens

every day.

Discussions

Identification discussions are very important, and a key to success is representing all

relevant viewpoints, including stakeholders as well as different parts of the operations

staff. This is a powerful way to expose assumptions and differing viewpoints.

The ultimate goal of the identification discussion is to improve the team’s risk

management. Measure progress against that goal by the substance of the discussion, not

by the number of words in the risk statement it produces, or by how many minutes it

takes to create each risk statement. Sometimes the most valuable discussions take the

most time and yet produce the fewest words. This is especially true when the team first

starts using the risk model for operations.

Thinking about risk is a skill that takes time to develop, and it is far easier to develop in

group discussions than alone in an office.

Risk Model for Operations

17

Source-Mode Matrix

The set of all possible conditions is nearly infinite, and the sheer volume can make it

hard for the team to focus on one at a time, especially during brainstorming. An

effective solution, and one that has benefits later in the process, is to subdivide all of the

possible conditions into a table with one row for each of the four sources of risk, and

one column for each of the four modes of failure:

Mode of failure

Cost

Source

of risk

Agility

Performance

Security

People

Process

Technology

External

The team can then focus on one cell of the table at a time. For example, team members

might ask themselves, “How might people in the operations group make mistakes that

would cause us to do the right work at too high a cost?” Or they might ask, “How could

our technology fail to meet customers’ performance expectations? Or more specifically,

how might hardware problems cause the sales group’s order entry system to bog

down?”

The Risk Statement

Before a team can manage a risk, the team must clearly express it, and in practice this

can be a bigger challenge than it seems at first:

Phrasing a risk often requires rethinking assumptions about a situation and

reevaluating the elements that are most important.

Writing down risks is critical, yet for various reasons the risks a person has thought

through often stay locked inside his or her mind. The team can’t manage a risk that

isn’t shared.

The risk statement should include all parts diagrammed in the example below. Note that

the condition and the two consequences reflect the risk’s source of risk and mode of

failure, respectively.

Risk Model for Operations

Operations

Consequence

Security

Performance

Agility

Cost

Mode of

Failure

Source of

Risk

18

Condition

... then

operations will

suffer this

loss of

performance ...

People

If people do

this ...

Process

Technology

External

Business

Consequence

... which will

harm the

business in this

way...

Figure 6 - The risk statement

Risk Statement Form

A helpful way to present the information gathered during this step is through a risk

statement form, which may add information that will be valuable later, during the risk

tracking step. In addition to the five parts of the risk statement (condition, source of risk,

mode of failure, operational consequence, business consequence), the statement form

should include the following:

Role or function. The service management function most directly involved with the

risk situation.

Risk context. A paragraph containing additional background information that helps

to clarify the risk situation.

Related risks.

Risk Factor Charts

A risk factor chart helps the group quickly determine the exposure it faces in general

categories of risk. One line of such a chart might look like this:

Risk

If a hard disk

fails, its data

cannot be

recovered from

tape backup.

Cues of High Exposure

Cues of Medium Exposure

Cues of Low Exposure

No one is formally

accountable for

performing backups.

Only one operator has

been trained on the new

version of the software.

The backup operator who

has been trained cannot

be reached except during

his/her shift.

Managers ensure that backups

are made every day, but

making them is a low-status

job assigned to operators with

the least seniority.

All backup operators attend a

one-hour class, but that

training covers only the backup

software User’s Guide and it

has no hands-on exercises.

Each week’s tapes are

sampled and restored to

verify integrity.

Two backup operators

are on shift at all times.

Only backup operators

who have vendor

certification are allowed

to make backups without

supervision.

Risk Model for Operations

19

Step 2: Risk Analysis

2

Figure 7

Risk analysis builds on the risk information generated in the identification step,

converting it into decision-making information. In the analyzing step, the team adds

three more elements to the risk’s entry on the master risk list: the risk’s probability,

impact, and exposure. These elements allow the team to rank risks, which in turn allows

the team to put the most energy into managing the most important risks.

Risk Probability

This is the likelihood that the condition will actually occur. Risk probability must be

greater than zero, or the operations risk does not pose a threat to the business. Likewise,

the probability must be less than 100 percent or the risk is a certainty—in other words, it

is a known problem.

The probability can also be seen as the likelihood of the consequence, because if the

condition occurs, the probability of the consequence is assumed to be 100 percent.

Risk Impact

Risk impact measures the severity of adverse effects, or the magnitude of a loss, caused

by the consequences.

The most effective solution is a numeric scale. Deciding how to estimate losses is not a

trivial matter. The best solution is a numeric scale: the larger the number, the greater the

impact. As a rule of thumb, the scale should go at least as high as three, in order to

produce a range of exposure values. However, note that the higher the scale goes, the

more time people spend picking exactly the right number, without producing much real

additional accuracy.

20

Risk Model for Operations

Risk Exposure

The exposure is the result of multiplying the probability by the impact. Sometimes a

high-probability risk has low impact and can be safely ignored; sometimes a highimpact risk has low probability and can be safely ignored. The risks that have high

probability and high impact are the ones most worth managing, and they’re the ones that

produce the highest exposure values.

When estimating probability and impact, it is often valuable to note your confidence

level. For example, if a risk might result in a million-dollar loss but the confidence that

the data are accurate is only 20 percent, document it so that the people who review the

risk analysis can put this estimate in proper perspective.

Best Practices

These best practices will be beneficial during the risk analysis step.

Settle Differences of Opinion

It is unlikely that a team will agree on risk ranking because team members with

different experiences or viewpoints will rate probability and impact differently.

Discussions can easily turn emotional, or at least political, and to maintain objectivity in

the discussion and to limit arguments, be sure to decide as a team how to resolve these

differences before starting this step. Options include a majority-rule vote, picking the

worst-case estimate, or siding with the person who has the longest experience dealing

with the situation in which the risk occurs.

Measure Financial Impact

It is often helpful to roughly estimate the impact in financial terms, and record this in

addition to the impact’s numeric estimate. If several risks have the same exposure value

then the financial estimate can help determine which one is most important. Also, the

financial data helps in the planning step to ensure that the cost of preventing a risk is

lower than the cost of incurring the consequences.

It might seem that the financial estimate is preferable, and could be used in place of a

numeric value. However, in practice, financial impact values tend to be a much more

labor-intensive way to produce the same top risks list.

If you decide to use a monetary scale for impact, use it for all risks. If one risk’s impact

uses a numeric scale and another’s uses a monetary scale, then the two can’t be

compared to each other, so there’s no way to rank one over the other.

Perform a Business Impact Analysis

Perform a business impact analysis, for example using a questionnaire that IT users fill

out, estimating the importance and impact of service outages. This can help IT

understand the services’ perceived value, and this might be a factor to consider when

ranking risks.

Record the Impact’s Classification

Some IT groups find it useful to categorize the nature of the impact, such as capital

expenditure, legal, labor, and so on.

Risk Model for Operations

21

Step 3: Risk Action Planning

3

Figure 8

The planning step turns risk information into decisions and actions. Planning involves

developing actions to address individual risks, prioritizing the actions related to each

risk, and creating an integrated risk management plan.

Key tasks within this step include defining three more elements of the risk: mitigations,

triggers, and contingencies.

Mitigations

Mitigations are steps the team can take before the condition occurs, and each has one of

three effects on the risk:

Reduce. Risk reduction minimizes the risk’s probability or its impact, or both. For

example, redundancy generally reduces the impact of failure. If one component fails

there is no impact because the redundant component is still working. Keeping track

of those components’ expected lifespan and replacing them before they’re expected

to fail reduces the probability of the failure. Ideally, a reduction method reduces

probability or impact to zero, but this is not always possible.

Avoid. Risk avoidance prevents the team from taking actions that increase exposure

too much to justify the benefit. An example is upgrading an unimportant, rarely used

application on all 50,000 desktops of an enterprise. In most cases, the benefit doesn’t

justify the exposure, so IT avoids the risk by not upgrading the application.

Transfer. Whereas the avoidance strategy eliminates a risk, the transference

strategy often leaves the risk intact but shifts responsibility for it to another group.

For example, a company with an e-commerce site might outsource credit

verification to another company. The risks still exist, but they become the outsource

partner’s responsibility. However, if the outsource partner is better able to perform

credit verification, then transferring the risks can also reduce them.

It is vitally important to assign an owner to every mitigation plan, and it is helpful to

define the plan’s milestones in order to track its progress, and its success metrics in

order to track whether it is having the desired effect.

22

Risk Model for Operations

Triggers

Triggers are indicators that tell the team a condition is about to occur, or has occurred,

and therefore it is time to put the contingency plan into effect.

When defining the risk elements, it can be difficult to distinguish between consequences

and triggers. Ideally, the trigger becomes true before the consequences occur. It may

help to think of them as warning lights that illuminate while there is still time to avoid

danger. For example, if the condition is that the server runs out of hard disk space, the

trigger might be that the server’s disk has reached 95 percent of its capacity and is

trending upward.

In some cases, the triggers may be date-driven. For example, if the condition is that a

newly ordered server might not arrive in time to support the launch of a mission-critical

application, a trigger might be set for the latest date on which the server could safely

arrive.

Contingencies

A contingency is a step the team takes if the condition occurs or a trigger becomes true.

The contingency plan documents the set of contingencies the team will use when

reacting to a particular condition.

Continuing the previous example, if the server does not arrive in time and the trigger

becomes true, one contingency might be to borrow an existing server from a lessimportant service.

If the condition is that the server runs out of disk space, a trigger might be set to notify

operators when only 5 percent of the disk is still free. One contingency might be to free

disk space by moving little-used files to another server. Another contingency might be

to shut down non-critical applications so that a mission-critical one has no competition

for the remaining 5 percent of the disk’s space.

Best Practices

This best practice will be beneficial during the risk action planning step.

Prioritize

A mitigation plan might have several actions, and the sequence might affect the

mitigation’s success at reducing, avoiding, or transferring the risk, so it is important to

prioritize the steps in this plan.

A contingency plan is essentially a description of how to shift away from normal

operations when a condition occurs. Especially if the consequences disrupt many

services, it may be valuable to bring some services back on line first. Decide beforehand

the order in which to restore service, and decide how long each part can be offline.

Risk Model for Operations

23

Step 4: Risk Tracking

4

Figure 9

During the tracking step, the team gathers information about how risks are changing;

this information supports the decisions and actions that will be made in the next step

(control).

This step monitors three main changes:

Trigger values. If a trigger becomes true, the contingency plan needs to be

executed.

The risk’s condition, consequences, probability, and impact. If any of these

change (or are found to be inaccurate), they need to be reevaluated.

The progress of a mitigation plan. If the plan is behind schedule or isn’t having the

desired effect, it needs to be reevaluated.

This step monitors the above changes on three main timeframes:

Constant. Many risks in operations can be monitored constantly, or at least many

times each day. For example, automated tools can monitor a Web server’s

bandwidth usage every few seconds.

Periodic. The team periodically reviews the top risks list, looking for changes in the

major elements. This often happens at team meetings, change advisory board

meetings, and so on.

Ad-hoc. In some cases, someone simply notices that part of a risk has changed.

Risk Status Reporting

For operations reviews, the team should show the major risks and the status of risk

management actions. If operations reviews are regularly scheduled (monthly or at major

milestones), it helps to show the previous ranking of risks as well as the number of

times a risk was in the “top risk” list.

24

Risk Model for Operations

Best Practices

This best practice will be beneficial during the risk tracking step.

Review Routinely

Make risk review a part of regular work. This typically means making it a permanent

agenda item for any recurring meeting. The review can be highly effective without

taking very much time. This is the key to managing risks continuously.

Review Triggers

If the team has highly visible triggers that are automated and constantly monitored, it

can be easy to focus on them and overlook triggers that can’t be automated. Forgetting

to review triggers during a team meeting means that if one of them has become true, it

won’t be noticed until the next meeting, further delaying the contingency plan, and

often compounding the consequences.

Review Trends

Look for trends in risk data. For example, if a particular risk’s probability has increased

5 percent every week for the last month, then even though the probability is still low,

the trend may justify ranking the risk higher on the top risks list.

Step 5: Risk Control

5

Figure 10

The previous step (tracking) gathers information about a risk, and when something

changes, the controlling step executes a planned reaction to the change:

If a trigger value has become true, then execute the contingency plan.

If a risk has become irrelevant, then retire the risk.

If the condition or a consequence has changed, then redirect to the identification step

to reevaluate that element.

If the probability or impact has changed, then redirect to the analyzing step to update

the analysis.

If a mitigation plan is no longer on track, then redirect to the planning step to review

and revise the plan.

At first this step may not seem necessary, and the distinction between it and the tracking

step may be unclear. In practice, the need to act is often detected by a tool, or by people

who don’t have the required responsibility, authority, or expertise to react on their own.

The controlling step ensures that the right people act at the right time.

Risk Model for Operations

25

For example:

An automated tool might constantly monitor a Web server’s bandwidth usage. A

trigger has been defined so that if the usage jumps 10 percent in 10 minutes, then the

tool pages an operator who can execute a contingency plan by allocating more

bandwidth to the server. Detecting the change is part of the tracking step, paging the

operator is the transition from tracking to control, and the operator’s action is the

controlling step.

The IT group might not have the expertise to operate certain applications involved

with e-commerce, and that lack of expertise creates certain risks. Suppose that

another company is contracted to manage those applications, so some of those risks

may no longer be relevant. Realizing that some risks might now be irrelevant is part

of the tracking step. The controlling step starts the reevaluation, and if the risk is

found to be irrelevant, the controlling step retires the risk.

Suppose someone researches security problems and finds that the impact of a known

risk may be much smaller than its current estimate. Realizing the need to reevaluate

the risk is the tracking step. In the controlling step someone is assigned to reevaluate

the probability, and control of the risk passes to the analyzing step where the

probability can be reviewed.

Suppose a mitigation plan was designed to reduce a particular risk’s probability by

20 percent within three months. A periodic review of the mitigation plan shows that

in the first two months it has reduced the probability only 5 percent, and the risk

owner is told to investigate the shortfall. The periodic review is the tracking step.

The controlling step consists of notifying the owner that the mitigation plan needs

reevaluating.

Best Practices

The controlling step relies heavily on effective communication, both to receive

notification that parts of risks and plans have changed, and to ensure that the right

people take action at the right time. The controlling step can’t be effective unless

communication within IT is also effective.

26

Risk Model for Operations

Relating the Risk Model to MOF

One of Three Core Models

MOF is a collection of best practices, principles, and models. It provides comprehensive

technical guidance for achieving mission-critical production system reliability,

availability, supportability, and manageability on Microsoft’s products and

technologies.

MOF is composed of three core models that are closely integrated with each other:

The process model for operations

The team model for operations

The risk model for operations

The process model defines a set of service management functions (SMFs) and four

review milestones that provide operational integrity in the IT infrastructure. The team

model consists of a set of operations team role clusters that efficiently support the

operations process. The associated risk model manages the risks inherent in the IT

operations.

Additionally, MOF is based on and recognizes the current industry best practices for IT

service management that have been documented in the Central Computer and

Telecommunications Agency’s (CCTA) IT Infrastructure Library.

Risk Model for Operations

27

The MOF Process Model

MOF simplifies the complex set of dynamics involved in the IT operations

infrastructure into a framework that is easy to understand and whose principles and

practices are easy to incorporate and apply. The power of this simplified approach will

enable the operations staff of an enterprise of any size, regardless of maturity level, to

realize tangible benefits to the existing, or proposed, operations.

The MOF process model has four main concepts that are key to understanding the

model:

IT service management, like software development, has a life cycle.

The life cycle is made up of distinct, logical phases that run concurrently.

Each phase has an operations review process. Operations reviews must be release

based and time based.

IT service management touches every aspect of the enterprise.

With this understanding, the MOF process model consists of four integrated phases or

“quadrants”:

Changing

Operating

Supporting

Optimizing

These quadrants form a spiral life cycle that can be applied to a specific application, a

data center, or an entire operations environment with multiple data centers, including

outsourced operations and hosted applications.

Each quadrant culminates with a review milestone specifically tailored to assess the

operational effectiveness of the preceding quadrant. These quadrants, coupled with their

designated review milestones, work together to meet organizational goals and

objectives.

The following diagram illustrates the MOF process model and the relationship of the

life cycle quadrants, the reviews following each quadrant, and the concept of IT service

management at the core of the model. The diagram depicts each quadrant of the IT

operation connected in a continuous spiral life cycle.

28

Risk Model for Operations

Figure 11 - MOF and IT service management functions

Service Management Functions

IT SMFs are the core of the MOF process model. Although no SMF is exclusive to a

given quadrant in MOF, each SMF has a “home” quadrant or primary planning and

execution quadrant. Grouping SMFs with a primary MOF quadrant is a more intuitive

way to introduce an SMF in the context of the process model. The following is a

comprehensive list of MOF SMFs along with their description.

Changing

Change management. Responsible for managing any change in the organization.

Configuration management. Responsible for identifying, recording, tracking, and

reporting key IT components or assets.

Release management. Facilitates the introduction of software and hardware releases

into the managed IT environment.

Risk Model for Operations

29

Operating

Security administration. Responsible for maintaining a safe computing environment.

System administration. Responsible for keeping the enterprise systems running.

Network administration. Designs and manages all networks within an organization.

Service monitoring and control. Allows operations to observe the health of an IT

service in real time.

Directory services administration. Allows users and applications to find network

resources such as users, servers, applications, tools, services, and other information over

the network.

Storage management. Deals with on-site and off-site data storage for the purposes of

data restoration and historical archiving.

Job scheduling. Deals with assigning batch processing tasks at different times to

maximize the use of system resources while not compromising business and system

functions.

Print and output management. Deals with all data that is printed or compiled into

reports that are distributed to various members of the organization.

Supporting

Service desk management. Responsible for first-line support to the user community for

problems associated with the use of IT services.

Incident management. Manages and controls faults and disruptions in the use or

implementation of IT services as reported by customers or IT partners.

Problem management. Investigates and resolves the root causes of faults and

disruptions that affect large numbers of users.

Failover and recovery. Ensures that if a failure occurs, services are available in

accordance with the service continuity plan and service level agreements.

30

Risk Model for Operations

Optimizing

Service level management. Responsible for planning, coordinating, drafting, agreeing,

monitoring, and reporting on service level agreements (SLAs), and the ongoing review

of service achievements to ensure that IT and business are aligned and that service

quality is cost justifiable.

Capacity management. Ensures that appropriate IT resources are available to meet

business requirements.

Availability management. Concerned with the availability and reliability of the overall

system.

Financial management. Provides sound management of monetary resources in support

of organizational goals.

Workforce management. Recommends best practices to continuously assess key

aspects of the IT.

IT service continuity management. Focuses on preventing service outages and also on

recovery planning.

With regard to risk management, it is worth noting that some SMFs traditionally do

quite a bit of risk management. The obvious example is IT service continuity

management (formerly known as contingency planning), which focuses on disaster

recovery but employs risk management techniques. Availability management also relies

on risk management to ensure that changes in the environment don’t impact service

availability.

Risk Model for Operations

31

The MOF Team Model

The MOF team model offers guidelines for IT service management based on a set of

consistent, quality goals that exist in successful IT operations at organizations of various

sizes, from large corporate IT departments to smaller, growing e-business data centers

and application service providers.

The team model describes:

How to structure operations teams.

The key activities, tasks, and skills of each of the role functions.

What guiding principles to uphold to be most successful at running and operating

distributed computing environments on the Microsoft platform.

The following diagram illustrates the MOF team model and each team’s associated

SMFs.

intellectual property protection

network & system security

intrusion detection

virus protection

audit and compliance admin

contingency planning

maintenance vendors

environment support

managed services,

outsourcers, trading

partners

software/hardware

suppliers

change management

release/systems engineering

configuration control/asset

mgmt

software distribution/licensing

quality assurance

Release

Security

Infrastructure

enterprise architecture

infrastructure engineering

capacity mgmt

cost/IT budget mgmt

resource & long range

planning

service desk/helpdesk

production/product support

problem management

service level management

Communication

Support

Partner

Operations

messaging ops

database ops

network admin

monintoring/metrics

availability mgmt

Example Function Teams within Ops Team Model Roles

Figure 12

32

Risk Model for Operations

Comparing the Risk Model for Operations to Other Risk Models

Beyond Security

Many risk models focus on security and view management of risks from the perspective

of maintaining hardware and data security and integrity. One example is the CCTA’s

Risk Analysis and Management Methodology (CRAMM). This is a valuable approach,

but the risk model for operations broadens the scope of potential risks beyond security

to include risks related to people, process, and technology.

CRAMM

Sanctioned by ITIL, CRAMM was developed by Insight Consulting. CRAMM is a

structured method for assessing risks to information systems and identifying appropriate

countermeasures. As such, MOF acknowledges the value of this approach.

When comparing the security aspects of risk management, CRAMM’s structured

approach, embodied in a software package, is a three-step process that allows users to

identify the valuation of their assets, assess the threats and vulnerabilities, and then

apply recommended countermeasures to their IT infrastructure.

Comparison with Risk Model for Operations

MOF risk management as applied to security provides guidance and stresses continual

review of security risks in five steps. MOF risk management emphasizes the continual

process of identifying, analyzing, planning, tracking, and controlling security measures

because new security threats are continually surfacing.

Moreover, MOF recognizes that security management is just one component of

managing risks in the operations environment. Where the MOF risk model differs from

other risk models is that it takes on a comprehensive view of risk management that

includes risks associated with agility, performance, and cost in addition to security.

From the business perspective, an IT operation can have a tight security structure that

takes into account and manages potential security threats, but it still could fail if it

doesn’t address the risks inherent in agility, performance, and cost.

Risk Model for Operations

33

Examples

Risk Management in Each Role

The first section of this white paper made the case that business is changing and

operations needs new risk management tools in order to adjust. The second section

described the theory behind the risk model for operations. This section demonstrates

that the risk model for operations actually works when applied to real-world operations

risks.

A basic principle of the risk model for operations is that risk management should be

integrated into every role in the MOF team model. The examples below are organized

according to those roles. For each role, a representative SMF has been selected.

MOF Team Role

Release

Infrastructure

Support

Operations

Partner

Security

SMF

Configuration management

Capacity management

Service desk

Availability management

Financial management

Security

Please note that:

All of the SMFs in MOF are important and operations needs to manage risks in

each. One has been selected here for each role simply to avoid presenting an

unmanageable number of examples.

The examples below have been chosen to demonstrate the model’s applicability to

the widest audience. They are not intended to be comprehensive or exhaustive.

Microsoft Consulting Services consultants and partner consultants can help

demonstrate the application of these principles to a particular operations

environment.

Detailed analysis of each risk below is presented in Appendix B.

34

Risk Model for Operations

Release Role

The configuration management SMF is most commonly associated with this role.

Configuration management is responsible for the identification, recording, tracking, and

reporting of key IT components or assets. The goal of configuration management is to

ensure that only authorized configuration items are used in the IT environment and that

all changes to configuration items are recorded and tracked through their component life

cycle.

Suppose someone is doing configuration management work related to the deployment

of Microsoft® Windows® 2000. Recently, the team has debated the level of detail to

collect on the systems being upgraded. If the team collects too much information it may

fall behind schedule, but what if it collects too little? An operational consequence might

be that the other SMFs don’t have the information they need to perform correctly, so

problems occur that would have been easy to prevent. Once recognized, the team could

mitigate the risk by collecting additional detail.

Infrastructure Role

The capacity management SMF is most commonly associated with this role.

Suppose someone is doing capacity management work at an application service

provider (ASP). This person spends considerable time analyzing statistics generated by

various tools. Everyone in the group is impressed by the volume of detail that a new

tool provides, so much that it can be hard to find the most important measurements.

What if it becomes too hard to spot them? One consequence might be that outages and

bottlenecks seem to occur without warning, which severely impacts customer

satisfaction. Mitigations include reconfiguring the user interface, upgrading the tool, or

replacing it with one that does not pose this risk. If none of these are an option, or if

they will take time to implement, a contingency is to add capacity in hopes of staying

ahead of demand.

Risk Model for Operations

35

Support Role

The service desk SMF is typically associated with the support role from the MOF team

model.

The service desk function is responsible for first-line support to the user community for

problems associated with the use of IT services. The service desk also attempts to

identify a problem or rectify a known error through discrepancies or incidents

communicated by users. A service desk may be an organizational unit composed of

multiple service groups—for example, a call center and one or more site support teams.

Suppose that service desk personnel are working to recover service levels at a businessto-customer (B2C) e-commerce site. The customers are encountering problems and

reporting them, and the incident management staff are trying to gather all the relevant

information, but the automated tool they use (a database front end) wasn’t designed to

accept information that is critical to the problem. For example, the front end might

include hard-coded fields for items like the customer’s computer make and model, but

not the bandwidth of the line they use to connect to the Internet. This would prevent the

correct information from reaching the problem management group, which would slow

its response to problems and leave customers with the impression that the company isn’t

committed to providing good service. The group can try to change the tool if possible,

or work around the problem by repurposing existing fields to store the newly needed

data.

Operations Role

The operations role from the MOF team model often provides availability management.

Availability management is concerned with the availability and reliability of the overall

system. The goal of availability management is to ensure optimal availability of IT

services with the correct use of resources, methods, and technology.

Someone in the operations role, performing availability management, might realize that

if the group’s staffing were to drop, the group would not be able to meet the required

service levels. In particular, there are rumors of a merger with another company. If that

happens, then some IT staff roles are likely to be cut. If the staff levels are cut, the

messaging service would experience more frequent failures and it would take longer to

recover from each, which would reduce the company’s internal productivity, and

damage its reputation with other companies. Automated tools might reduce the impact

of the staff cuts, and if the cuts take place the availability management group might

borrow resources from other departments or hire contingent staff, and reset customer

expectations about service levels.

36

Risk Model for Operations

Partner Role

The partner role includes a broad collection of IT partners, service suppliers, and

outsource vendors who work as virtual members of the IT staff in providing hardware,

software, networking, hosting, and support services. The degree to which an IT

organization utilizes supplier services varies widely from business to business,

depending on the size, location, industry type, and the strategic goals of the business.

Internet e-businesses, for example, will focus on their core competencies of building

and running an e-commerce site, while they might outsource their customer service and

product fulfillment, hardware support, and possibly other functions.

The partner role is most closely associated with the financial management SMF.

Financial management encompasses many of the same accounting principles found in

use today across a wide variety of industries. In common practice today, cost

management for IT includes budgeting, cost accounting, cost recovery, cost allocations,

charge-back models, and revenue accounting. The key aspects of financial management

that ITIL and MOF address are its linkage to other service management functions.

This role is often responsible for service level agreements and maintenance contracts,

such as the ones that govern how one company might outsource part of its operations

work to another company. Outsourcing often makes financial sense, and it can be a risk

management strategy by itself: It transfers certain risks to the vendor or contractor.

However, this doesn’t mean the company is immune to external sources of risk, such as

a tightening of the labor market. One consequence of that risk is that operational costs

go up, which can impact other IT budgets. Labor-saving tools can somewhat reduce

impacts such as high turnover, less-skilled staff, and decreased staff availability

resulting from the need for additional training. The group might react to this market by

implementing non-monetary reward systems to encourage staff retention.

Security Administration Role

Security administration is responsible for maintaining a safe computing environment.

Security is an important part of the infrastructure of the enterprise.

This role and SMF are critical in nearly every environment. Someone in this role might

face many risks while managing security in a business-to-business e-commerce site that

one company uses to facilitate transactions with its business partners. For example, if

business management understands the needs and the costs of maintaining security, then

this role’s job is easier. What might happen if management does not have a realistic

understanding of security costs, and underfunds this role? One possible consequence is

that an under-funded staff does not properly protect partner data, leading to lawsuits.

The security staff can mitigate the risk by convincing upper management that additional

funding is required, and if that does prevent the condition from occurring, the staff

should at least prioritize their work to ensure they do the best job they can with the

limited resources.

Risk Model for Operations

37

Conclusion

Making Risk Management Easier

Most IT groups have seen the changes described above: business becoming more reliant

on IT, computing environments becoming more complex, visibility to the outside world

increasing, and IT groups having less control. The risks are getting bigger, but the risk

model for operations makes them easier to manage through the principles of proactive

management, and embedding risk management in all processes and all roles.

The example risk statements above are intended to prove this point, to demonstrate how

the risk model for operations can be applied to real-world situations. A larger set of

specific risk statements will be made available, especially through guides released by

OpsCentral, and through the personalized assistance of MCS and Microsoft’s consulting

partners.

Additional Information

Courses

For course availability, see http://www.microsoft.com/es.

A MOF course is being developed and will be available shortly.

Books

The following book serves as a bibliography for this paper or as recommended reading

to further understand the concepts contained herein:

IT Service Management. IT Service Management Forum/CCTA. ITIMF Ltd., 1995.

38

Risk Model for Operations

Web Sites

For more information on Microsoft’s enterprise frameworks and offerings, see: