lesson03

Software Paradigms

Software Paradigms (Lesson 3)

Object-Oriented Paradigm (2)

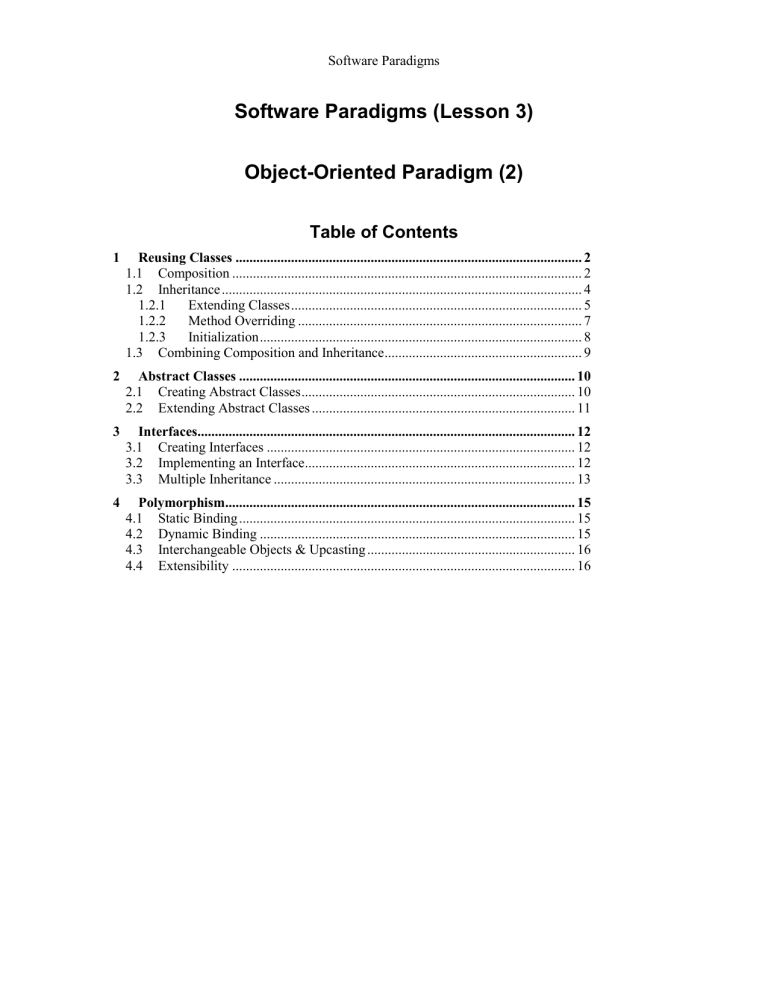

Table of Contents

1 Reusing Classes .................................................................................................... 2

1.1

Composition ..................................................................................................... 2

1.2

Inheritance ........................................................................................................ 4

1.2.1

Extending Classes .................................................................................... 5

1.2.2

Method Overriding .................................................................................. 7

1.2.3

Initialization ............................................................................................. 8

1.3

Combining Composition and Inheritance ......................................................... 9

2 Abstract Classes ................................................................................................. 10

2.1

Creating Abstract Classes ............................................................................... 10

2.2

Extending Abstract Classes ............................................................................ 11

3 Interfaces ............................................................................................................. 12

3.1

Creating Interfaces ......................................................................................... 12

3.2

Implementing an Interface .............................................................................. 12

3.3

Multiple Inheritance ....................................................................................... 13

4 Polymorphism ..................................................................................................... 15

4.1

Static Binding ................................................................................................. 15

4.2

Dynamic Binding ........................................................................................... 15

4.3

Interchangeable Objects & Upcasting ............................................................ 16

4.4

Extensibility ................................................................................................... 16

Software Paradigms

1 Reusing Classes

Once a class has been created and tested, it should (ideally) represent a useful unit of code. If it happens that such a class has a good design and is useful we might want to reuse this class. Code reuse is one of the greatest advantages that object-oriented programming languages provide.

There are two possibilities to reuse classes in object-oriented programs:

Reusing implementation

Reusing interface

If we want to reuse implementation we basically compose a new class from the already existing classes, thus creating a composite class. We say that the composite class reuses the implementation from its components.

On the other hand, if we want to reuse interface of a class we create a subclass of that class. Then we say that the subclass inherits functionality (methods) from the superclass. Thus, the subclass reuses the interface of the superclass.

1.1 Composition

The simplest way to reuse a class within a new class is to place an object of that class inside the new class. The new class can be made up of any number and type of other objects, in any combination that is required to achieve the functionality that is needed. Because we are composing a new class from existing classes, this concept is called composition ( aggregation ).

Composition is often referred to as a “has-a” relationship, as in “a car has an engine.”

Let us look on the following example to see how composition works. Suppose we want to create the class definition for simple 2D shape objects. Each shape object has a color, a position where it is placed on the screen, a dimension (width and height), and so on. Now, suppose that we already have classes that represent color objects, point objects and dimension objects. For instance, the

Color class might look as follows: public class Point{ private int x_; private int y_; public Point(){

} public Point(int x, int y){

} x_ = x; y_ = y;

Software Paradigms public int getX(){

} return x_; public int getY(){ return y_;

}

} public void setX(int x){ x_ = x; public void setY(int y){ y_ = y;

}

}

Suppose that similar to that the Color class and the Dimension class have been defined and that they encapsulate the RGB values, and the values for width and height, respectively. Further, they provide a number of methods to manipulate the encapsulated data, as well as constructors for a parameterized initialization of objects.

Now we might compose the Shape class from the Color, Point and Dimension classes: public class Shape{ private Color color_; private Point position_; private Dimension dim_;

} public Shape(){

} public Shape(Point position, Dimension dim){ this(position, dim, new Color(0, 0, 0));

} public Shape(Point position, Dimension dim, Color color){ position_ = position; dim_ = dim; color_ = color

// here comes some code

Software Paradigms

// … public Rectangle getBounds(){ return new Rectangle(position_.getX(), position_.getY(), dim_.getWidth(), dim_.getHeight());

} public void setBounds(Rectangle bounds){ position_.setX(bounds.getX()); position_.setY(bounds.getY()); dim_.setWidth(bounds.getWidth()); dim_.setHeight(bounds.getHeight());

}

}

In two methods, printed in bold in the above code, we see an example of providing the Shape class with a certain functionality (getting and setting the bounds) by reusing the functionality, which is already provided by the Point and Dimension classes.

Another interesting thing to notice in the above example is how we nested constructor calls. The second constructor, which takes a Point and a Dimension object calls the third constructor, which takes a Point, a Dimension and a Color object. This is achieved by using the self-reference of an object: this .

Summarizing, composition comes with a great deal of flexibility. The member objects of the new class are usually private, making them inaccessible to the client programmers who are using the class. This allows programmers to change those members without disturbing existing client code. They can also change the member objects at run-time, to dynamically change the behavior of the composed objects.

1.2 Inheritance

The second way to reuse a class code can be achieved through inheritance . Inheritance allows programmers to define a class as a subclass of an existing class. The subclass inherits in this way all instance variables and all methods from the basic class, as long as they declared as public or protected.

The level of inheritance can be arbitrarily deep. That means that we can create a subclass from a class that is already a subclass of another class. If we have more then one level of inheritance then a subclass inherits variables and methods from all of ancestors of its superclass.

Software Paradigms

The subclass can use the instance variables or methods as is, or it can hide the member variables or override the methods.

1.2.1

Extending Classes

The inheritance concept is called extending a class in Java. Thus, when we create a subclass of a class we say that we extend that class.

Let us look again on an example. We use again the same example from the previous section.

Suppose we have the Shape class representing 2D shapes that we can draw on the screen. In the previous section we presented this class to demonstrate the composition principle. Here we give the complete code for the Shape class. Note, that the code now includes methods that reflect a typical behavior that we would expect from the Shape class. Thus, we have methods that we can call in order to draw a shape or erase a shape for example. public class Shape{ protected Color color_; protected Point position_; protected Dimension dim_; public Shape(){

}

} public Shape(Point position, Dimension dim){ this(position, dim, new Color(0, 0, 0)); public Shape(Point position, Dimension dim, Color color){ position_ = position; dim_ = dim; color_ = color

}

} public void draw(Graphics g){

// here comes implementation public void erase(){

// here comes implementation

}

public Rectangle getBounds(){

Software Paradigms return new Rectangle(position_.getX(), position_.getY(), dim_.getWidth(), dim_.getHeight());

} public void setBounds(Rectangle bounds){ position_.setX(bounds.getX()); position_.setY(bounds.getY()); dim_.setWidth(bounds.getWidth());

} dim_.setHeight(bounds.getHeight());

}

Suppose now that we want to represent different Shape objects, such as circles, rectangles, polygons, triangles, ellipses, etc. Obviously all these objects are shapes and share the same characteristics and behavior, such as they all have a color, a position, a dimension, or they can all be drawn, moved, erased, and so on. However, they all differ from each other in some way. For example, a triangle has three distinct points, whereas a polygon can have 6 points, etc.

Obviously, the Shape class that we introduced represents very well the things that all shapes have in common, but we need more specialized classes in order to represent different shapes. These subclasses would extend the Shape class and add required instance variables or implement different, more specialized behavior. Thus, the Circle class would draw a circle on a user screen and the Triangle class would draw a triangle.

Note also that we changed the access modifiers for instance variables of the Shape class from private to protected. We did so because we want subclasses of the Shape class to obtain access to its instance variables.

Let us now look on an example for the Circle class: public class Circle extends Shape{ public void draw(Graphics g){

// here comes the Circle specific code

}

}

First, we notice the keyword extend , which declares a class to be a subclass of another class.

Then we see that the Circle class just overrides (implements in another way) the draw method of the basic Shape class in order to implement a specific behavior for circle objects.

Let us look now on another example: public class Polygon extends Shape{

Software Paradigms private Point[] points_;

} public Polygon(Point[] points){ points_ = points;

} public void draw(Graphics g){

// here comes the Polygon specific code

}

Note that the Polygon class not only overrides the draw method, but also adds a new, specific instance variable to the Polygon class. It is an array of Points that represent points of that polygon.

1.2.2

Method Overriding

The ability of a subclass to override a method in its superclass allows a class to inherit from a superclass whose behavior is "close enough" and then override methods as needed. We saw this already on the examples of the Circle and the Polygon class that override the draw method of the basic Shape class.

Let us look more closely on these two overridden methods: public class Polygon extends Shape{ public void draw(Graphics g){ g.setColor(color_); for(int i = 0; i < (points_.length – 1); i++) g.drawLine(points_[i].getX(), points[i].getY(),

points_[i+1].getX(), points_[i+1].getY());

}

// here is other code

}

Software Paradigms public class Circle extends Shape{ public void draw(Graphics g){

} g.setColor(color_); g.drawOval(position_.getX(), position_.getY(), dim_.getWidth(), dim_.getHeight());

}

Thus, we see that these two classes provide different implementations for the draw method and therefore a different behavior for the two classes.

Another important thing to notice is that the return type, method name, and number and type of the parameters for the overriding method must match those in the overridden method.

1.2.3

Initialization

Another important aspect of the inheritance mechanism is the initialization of objects of a subclass. Basically, an object of a subclass is an instance of both classes: subclass and superclass. Thus, a proper initialization of both “objects” has to be accomplished.

In Java, the default empty constructor of a class is automatically called when an object is created.

If a class is a subclass of another class then the Java system automatically invokes first the constructor of the superclass.

In the case that programmer wants to define constructors that takes arguments, then he/she has to call the constructor of the superclass by him/herself.

Let us look on the following example to demonstrate this: public class Polygon extends Shape{ private Point[] points_; public Polygon(Point[] points, Point position,

Dimension dim){ super(position, dim); points_ = points;

}

// here comes the rest

}

The code in bold calls the constructor of the superclass to initialize its instance variables properly.

Note that this call has to be the first thing that a subclass constructor executes.

Software Paradigms

1.3 Combining Composition and Inheritance

Sometimes we want to create more complex classes that possible combine composition and inheritance mechanism.

The following example shows the creation of a more complex class, using both inheritance and composition. Suppose that we want to have a composite shape object, which groups together a number of other shapes. In that way we can treat all shapes object that are put into the grouped object as just one shape object.

Obviously, such object is a special shape object, i.e., it can be represented by a subclass of the

Shape class and at the same time it is a composite object composed of say an array of other shape objects. The code for such Group class might look as follows: public class Group extends Shape{

} private Shape[] shapes_; public Group(Shape[] shapes){ shapes_ = shapes; public void draw(Graphics g){ for(int i = 0; i < shapes_.length; i++)

} shapes_[i].draw(g);

}

The cold in bold from the example above represents inheritance and composition mechanisms.

Software Paradigms

2 Abstract Classes

Sometimes, a class that we define represents an abstract concept and, as such, should not be instantiated. Rather it should just serve as a base superclass for a number of more specialized classes. That means a basic abstract class defines just an interface that should be shared among its subclasses.

Let us revisit our Shape class example and try to think about it in terms of an abstract class.

Basically, we used the Shape class just as a superclass for a number of different subclasses, such as the Circle, Polygon, Group class and so on. We didn’t use the Shape class to directly create instances of it.

If we think more about it we can conclude that it is not necessary to create instances of the Shape class, because an instance of a Shape class that is not also an instance of a special subclass is of no much use, because such Shape instance is not aware of how to draw itself, for example. It knows that it is a Shape but it doesn’t know which Shape it is.

Obviously, we could and should (to prevent creation of objects that don’t know how to draw themselves, for example) define the Shape class to be an abstract class. Technically, to define an abstract class means that we define a number of its methods to be abstract, i.e., we don’t provide the implementation for them but rather leave the subclasses to do so. Obviously, the draw method and for example the erase method of the Shape classes should be defined abstract, because special classes should implement this special behavior themselves.

2.1 Creating Abstract Classes

To create an abstract class we must declare it to be abstract and in addition to that we must declare a number of its methods to be abstract. Let us revisit the Shape class from above and define it to be an abstract class: abstract public class Shape{ protected Color color_; protected Point position_; protected Dimension dim_; public Shape(){

} public Shape(Point position, Dimension dim){ this(position, dim, new Color(0, 0, 0));

}

Software Paradigms public Shape(Point position, Dimension dim, Color color){

} position_ = position; dim_ = dim; color_ = color abstract public void draw(Graphics g); abstract public void erase(); public Rectangle getBounds(){ return new Rectangle(position_.getX(),

} position_.getY(), dim_.getWidth(), dim_.getHeight()); public void setBounds(Rectangle bounds){ position_.setX(bounds.getX()); position_.setY(bounds.getY()); dim_.setWidth(bounds.getWidth()); dim_.setHeight(bounds.getHeight());

}

}

Note the code in bold declaring the Shape class and two methods of it to be abstract.

Another important thing to notice here are constructors of the abstract Shape class. Although the

Shape class defines a number of constructors we cannot use these constructors directly to create instances of the Shape class. The only way we can use these constructors is from subclasses of the

Shape class. Thus, if we have a subclass of the Shape class, say the Polygon class, it can invoke as the first line in its constructor a constructor from the Shape class in order to initialize instance variables from the Shape class.

2.2 Extending Abstract Classes

Basically, extending an abstract class is same as extending a normal class. The only difference is that a subclass in order to become a normal class, i.e., a class from which we can create instances has to implement all abstract methods from its abstract superclass. Otherwise this subclass is considered to be an abstract class as well and therefore it is not possible to create its instances.

Software Paradigms

3 Interfaces

In the last section we saw in which way we can use and create abstract classes. Let us now think about an abstract class that has all its methods declared to be abstract. Obviously, such abstract class provides just an interface for all of its subclasses.

In Java this concept obtained a special keyword: interface . An interface defines a protocol of behavior that can be implemented by any class anywhere in the class hierarchy. An interface defines a set of methods but does not implement them. A class that implements the interface agrees to implement all the methods defined in the interface, thereby agreeing to certain behavior.

This class obtains also the type of that interface.

Because an interface is simply a list of unimplemented, and therefore abstract methods, what is the difference between an interface and an abstract class? The differences are significant:

An interface cannot implement any methods, whereas an abstract class can.

A class can implement many interfaces but can have only one superclass.

An interface is not part of the class hierarchy. Unrelated classes can implement the same interface.

3.1 Creating Interfaces

}

Let us now look on an example of an interface. We already saw how we can use collections to store objects of different types. We also introduced the concept of an iterator , which is an object that we use to traverse through the objects of a particular collection. The iterator object is a typical example of where we would use an interface instead of a class.

Basically, an iterator object allows us to go forth and back, for example, between members of a collection. These members are stored within that collection, but an iterator just agrees to traverse behavior. It does not contain the objects from that collection. We could define an iterator interface like this: public interface Iterator{ public Object next(); public boolean hasNext();

Note, the interface keyword in bold. We also see from the above example that an interface just declares a number of methods similarly to an abstract class. The difference here is that we don’t need to use the abstract keyword to do so.

3.2 Implementing an Interface

If a class chooses to extend an interface we say that this class implements that interface. The principle here is the same as with abstract classes. If a class implements an interface it should implement all of its methods in order not to be an abstract class. Otherwise the class is considered to be an abstract class and therefore we cannot create instances of that class.

Let us look on an example of a class that implements the Iterator interface from above:

Software Paradigms public class ArrayList implements Iterator{

}

} private int cursor_; public boolean hasNext(){ return (cursor_ != size()); public Object next(){ return get(cursor_++);

} public Iterator iterator(){ cursor_ = 0; return this;

// other code comes here

}

In the example above the ArrayList class implements the Iterator interface. The ArrayList class implements all methods declared in the Iterator interface, thus this class is not an abstract class and we can create its instances.

There are several important issues of the example above that we have to mention here:

ArrayList class implements itself the Iterator interface, therefore the method iterator returns this reference, i.e., the reference of the ArrayList object itself. Recollect that a class implementing an interface has also the type of that interface.

Because the ArrayList class implements the Iterator interface, the methods that override that interface might call other methods of the ArrayList directly. For example, the method next calls the method get of the ArrayList class.

Another class could be created, say ArrayListIterator, which could be a separate class only implementing the Iterator interface. In that case the iterator method from the

ArrayList class would create a separate instance of the ArrayListIterator class and return this instance.

3.3 Multiple Inheritance

As we mentioned before a class can extend another class in order to specialize its characteristics and its behavior. In some object-oriented languages a class can extend not only one class but also a number of other classes. This is called multiple inheritance .

There are a number of problems with this concept. For instance, suppose a class extends two classes that declare two same methods but with other implementations (e.g. in both classes we have one method with the same name, arguments and return values but with a different implementation). Now, if we call this method on an instance of the subclass, it is not clear to which code to bind it, i.e., should we call this method from the first or from the second superclass.

Software Paradigms

Such and similar issues caused that there is no support for pure multiple inheritance in Java. That means in Java a class can extend just one superclass.

However, this might be too restrictive in some cases and therefore Java supports “a kind of” multiple inheritance in the following way. A class in Java might implement a number of interfaces, thus it “inherits” from multiple sources. Since interfaces are just declarations of methods and there is no implementation defined by interfaces the problem that we described before does not exist in Java.

Software Paradigms

4 Polymorphism

Let us look again on the example of the Group shape class from above. Precisely, let us investigate in more details its draw method: public class Group extends Shape{

} public void draw(Graphics g){ for(int i = 0; i < shapes_.length; i++) shapes_[i].draw(g);

// …

}

An instance of the Group class holds an array of instances of other Shape classes, such as circles, polygons, triangles, etc. The draw method of the Group class iterates through all shapes and draws them one by one on the user screen. Lines of the code in bold above show the invocation of the draw method of each particular Shape object.

Here we encounter a very important mechanism in object-oriented languages. We call in our code the method of an instance of a base class (the Shape class), but at the run-time the system calls the right method of each particular object, i.e., if it encounters a circle object it calls the draw method of that circle object; if it encounters a polygon object it calls the draw method of the polygon object, etc. As the effect of that shape objects are drawn in the way we expect them to be drawn.

This mechanism is called polymorphism . Technically, due to polymorphism objects are interchangeable or substitutable in object-oriented programs. This means we can write code that talks to shapes and automatically handle anything that fits the description of a shape, i.e., handle anything that is a subclass of the Shape class.

Let us now examine how object-oriented programming languages implement polymorphism.

4.1 Static Binding

In traditional programming languages, e.g. in procedural programming languages such as C, the compiler makes a function call statically . It means the compiler generates a call to a specific function name, and the linker resolves this call to the absolute address of the code to be executed.

This principle is called static binding or early binding of a function call.

The static binding means that in the case of the above Shape example the compiler would bind the call to the draw method of the Shape class at the compile time, thus at the run-time the draw method of the base Shape class would be called for each particular shape object regardless of its real type.

4.2 Dynamic Binding

As we already saw static binding cannot be applied if we want to support polymorphism.

Therefore, object-oriented languages support another type of binding function calls. Binding supported by object-oriented languages is called dynamic binding or late binding .

Software Paradigms

Dynamic binding means that when you send a message to an object, the code being called isn’t determined until run-time. The compiler does ensure that the function exists and performs type checking on the arguments and return value, but it doesn’t know the exact code to execute.

To perform late binding, Java uses a special bit of code in lieu of the absolute call. This code calculates the address of the function body, using information stored in the object. Thus, each object can behave differently according to the contents of that special bit of code. When you send a message to an object, the object actually does figure out what to do with that message.

4.3 Interchangeable Objects & Upcasting

Polymorphism allows us to interchange (substitute) an object of the type A for an object of the type B, where the type A is a subclass of the type B (no matter at which level of inheritance). Let us look again on the Shape example:

Shape[] shapes = new Shape[2]; shapes[0] = new Circle(new Point(100, 100), 50); shapes[1] = new Polygon(new Point(0, 0), 100, 50);

Group group = new Group(shapes);

First, we notice that we substitute a circle and a polygon object for objects of its base Shape class

(e.g., shapes[0] and shapes[1]). We treat instances of inheriting classes as instances of a base class.

We call this process of treating a derived type as though it were its base type upcasting . The name cast is used in the sense of casting into a mold and the up comes from the way the inheritance diagram is typically arranged, with the base type at the top and the derived classes fanning out downward. Thus, casting to a base type is moving up the inheritance diagram: “upcasting.”

4.4 Extensibility

Polymorphism allows object-oriented programs to be easily extensible. Imagine that we write the code for another Shape class, say Ellipse class. It is clear that we don’t need to change the code for the Group class in order to include ellipse objects in new group objects. Since the Ellipse class is a subclass of the Shape class everything perfectly fits. It doesn’t matter that we created the

Ellipse class additionally.