Carris_Introduction to Fungi Copyright Table

advertisement

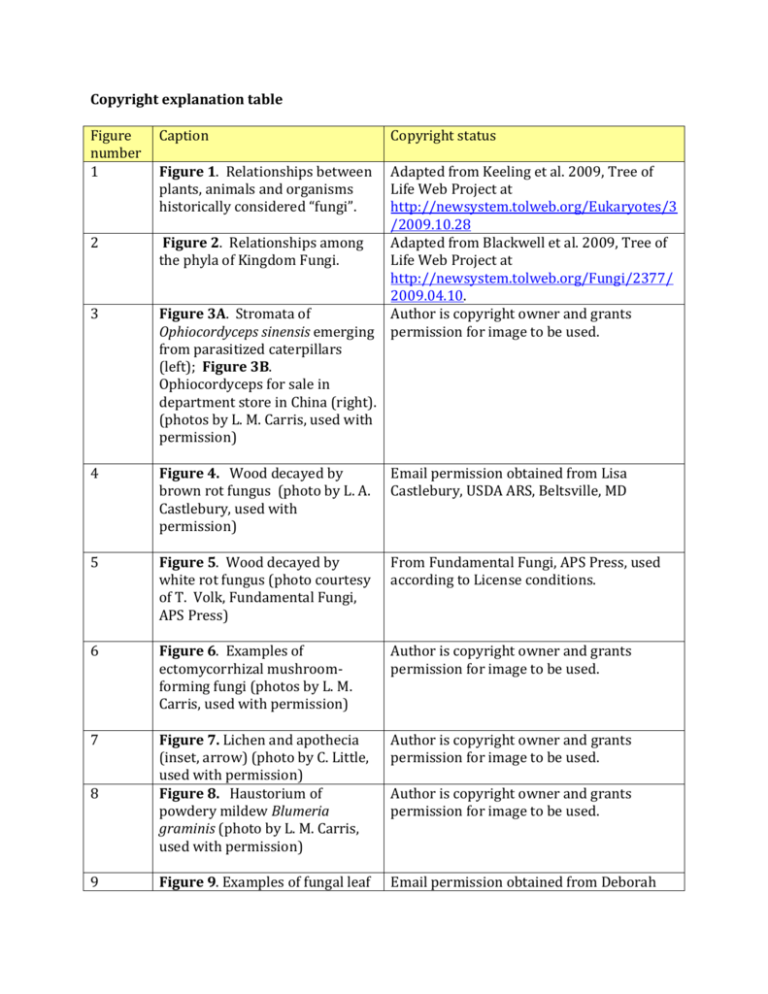

Copyright explanation table Figure number 1 Caption Copyright status Figure 1. Relationships between plants, animals and organisms historically considered “fungi”. 2 Figure 2. Relationships among the phyla of Kingdom Fungi. 3 Figure 3A. Stromata of Ophiocordyceps sinensis emerging from parasitized caterpillars (left); Figure 3B. Ophiocordyceps for sale in department store in China (right). (photos by L. M. Carris, used with permission) Adapted from Keeling et al. 2009, Tree of Life Web Project at http://newsystem.tolweb.org/Eukaryotes/3 /2009.10.28 Adapted from Blackwell et al. 2009, Tree of Life Web Project at http://newsystem.tolweb.org/Fungi/2377/ 2009.04.10. Author is copyright owner and grants permission for image to be used. 4 Figure 4. Wood decayed by brown rot fungus (photo by L. A. Castlebury, used with permission) Email permission obtained from Lisa Castlebury, USDA ARS, Beltsville, MD 5 Figure 5. Wood decayed by white rot fungus (photo courtesy of T. Volk, Fundamental Fungi, APS Press) From Fundamental Fungi, APS Press, used according to License conditions. 6 Figure 6. Examples of ectomycorrhizal mushroomforming fungi (photos by L. M. Carris, used with permission) Author is copyright owner and grants permission for image to be used. 7 Author is copyright owner and grants permission for image to be used. 8 Figure 7. Lichen and apothecia (inset, arrow) (photo by C. Little, used with permission) Figure 8. Haustorium of powdery mildew Blumeria graminis (photo by L. M. Carris, used with permission) 9 Figure 9. Examples of fungal leaf Email permission obtained from Deborah Author is copyright owner and grants permission for image to be used. spots: (A) Black spot of rose, (B) Colletotrichum leaf spot of English ivy, (C) Phyllosticta leaf spot of rhododendron, and (D) shot-hole symptom as seen in eggplant leaf spot. (photos courtesy of Deborah Miller, Davey Expert Tree Company, used with permission) Miller (Davey Expert Tree Company). 10 Figure 10. Examples of chlorotic halos surrounding fungal lesions in two fungal plant diseases: (A) sooty stripe of sorghum (Ramulispora sorghi) and (B) greasy spot of citrus (Mycosphaerella citri). (photo by C. Little, used with permission) Author is copyright owner and grants permission for image to be used. 11 Figure 11. Black knot caused by Apiosporina morbosa (photo courtesy of T. Volk, Fundamental Fungi, APS Press) From Fundamental Fungi, APS Press, used according to License conditions. 12 Figure 12. Galls and telial horns of Gymnosporangium juniperivirginiae (cedar-apple rust) in cedar tree. (Photos by Elizabeth Bush, Megan Kennelly, and John Olive, respectively, used with permission) Figure 13. Hyphae of Rhizopus stolonifera (photo by L.M. Carris, used with permission) Email permissions obtained from Elizabeth Bush (Virginia Tech), Megan Kennelly (Kansas State University), and John Olive (Auburn University). 14 Figure 14. Examples of fungal colonies belonging to the genus Fusarium in pure culture growing on artificial media. (A) Fusarium equiseti, (B) F. graminearum, (C) F. proliferatum, and (D) F. verticillioides (photos by C. Little, used with permission) Author is copyright owner and grants permission for image to be used. 15 Figure 15. Budding yeast cells Author is copyright owner and grants 13 Author is copyright owner and grants permission for image to be used. of Saccharomyces cerevisae. This yeast is important in the production of bread, wine and beer. (photo by L.M. Carris, used with permission) permission for image to be used. 16 Figure 16. Mature and developing asci of Pseudorhizina californica. Asci typically contain 8 ascospores as in ascus at bottom of image. (photo by L.M. Carris, used with permission) Author is copyright owner and grants permission for image to be used. 17 Figure 17. Basidium with developing basidiospores (photo by L. M. Carris, used with permission) Author is copyright owner and grants permission for image to be used. 18 Figure 18. General ascomycete life cycle. In order to form eight ascospores, which is typical, an additional round of mitosis must occur after meiosis. Haploid (n), dikaryotic (n+n), and diploid (2n) phases of the life cycle are denoted by thin, double, and thick lines, respectively. (Image by C. Little, used with permission) Author is copyright owner and grants permission for image to be used. 19 Figure 19. Mature and developing asci of Pleospora sp. Each mature ascus contains eight dark brown, multicellular ascospores. (photo by L. M. Carris, used with permission) Figure 20. Fission yeast, Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Cells reproduce by fission—note cells in process of division. Asci containing four ascospores also present. (photo by L. M. Carris, used with permission) Figure 21. Peach Leaf Curl Author is copyright owner and grants permission for image to be used. 20 21 Author is copyright owner and grants permission for image to be used. From Fundamental Fungi, APS Press, used caused by Taphrina deformans (photo courtesy of A. B. Baudoin, Fundamental Fungi, APS Press) according to License conditions. 22 Figure 22. Asci containing ascospores, Taphrina deformans; asci are formed when the fungus ruptures the cuticle of the infected host. (photo by G. J. Weidman, Fundamental Fungi, APS Press) From Fundamental Fungi, APS Press, used according to License conditions. 23 Figure 23. Yeast cells and asci with two ascospores of Williopsis saturna (photo by L. M. Carris, used with permission) Figure 24. Rock lichens (photo by L. M. Carris, used with permission) Author is copyright owner and grants permission for image to be used. 25 Figure 25. Cleistothecia developing in culture of Emericella nidulans. White arrow indicates a cleistothecium. (photo by Richard Todd, used with permission) Email permission received from Richard Todd, Kansas State University 26 Figure 26. Conidia and conidiophores of Aspergillus (left) and Penicillium (right) (photo by L. M. Carris, used with permission) Figure 27. Cross-section of a blue cheese wedge showing accumulations of Penicillium (often P. roquefortii) mold (white arrow) giving the cheese its distinct smell and flavor. (photo by C. Little, used with permission) Author is copyright owner and grants permission for image to be used. Figure 28. Mature and immature chasmothecia of Erysiphe penicillata from lilac. Several asci are emerging through fissure Author is copyright owner and grants permission for image to be used. 24 27 28 Author is copyright owner and grants permission for image to be used. Author is copyright owner and grants permission for image to be used. (chasm) in wall of the mature chasmothecium. Note the dicotomously branched appendages on mature chasmothecium (photo by L. M. Carris, used with permission) 29 30 31 32 33 Figure 29. Powdery mildew (Erysiphe palszewskii) on Siberian peashrub (Caragana arborescens). Photo on left shows the white fungal growth on leaves that is characteristic of powdery mildews. Photo on top right shows a dichotomously branched appendage from a chasmothecium, and photo on bottom right shows asci emerging from chasmothecium. (photo on left by C. Nischwitz, photos on right by L. M. Carris) Figure 30. Orange apothecia of Caloscypha fulgens, a common spring cup fungus in the U.S. Pacific Northwest. (photo by L. M. Carris, used with permission) Figure 31. Black morels (Morchella elata group), another common spring fungus in the U.S. Pacific Northwest. (photo by L. M. Carris, used with permission) Email permission received from Claudia Nischwitz (Utah State University) for photo on left. Autho is copyright owner and grants permission for two images on right to be used. Figure 32. Peaches infected by Monilinia fructicola. As the infected fruits dry, they form “mummies” which will fall to the ground, overwinter, and produce apothecia in the spring. (photo courtesy of A. B. Baudoin, Fundamental Fungi, APS Press) Figure 33. Apothecia of Monilinia fructicola forming from mummified peaches (photo courtesy of Plant Pathology Department, University of From Fundamental Fungi, APS Press, used according to License conditions. Author is copyright owner and grants permission for image to be used. Author is copyright owner and grants permission for image to be used. From Fundamental Fungi, APS Press, used according to License conditions. Arkansas, Fundamental Fungi, APS Press) 34 Figure 34. Perithecium of Coniochaeta sp. The ostiole is located in the darkened apical portion of the perithecium, and asci containing dark ascospores can be seen through the wall of the perithecium. (photo courtesy of B. Kendrick, Fundamental Fungi, APS Press) 35 Figure 35. (A) Apple scab lesions From Fundamental Fungi, APS Press, used on the abaxial surface according to License conditions. (underside) of crabapple leaves caused by Venturia inaequalis. (B) Cross section through pseudothecium in scab lesion (photo courtesy of W. E. MacHardy, Fundamental Fungi, APS Press) 36 Figure 36. Conidiophores and conidia of Alternaria spp. (photo by C. Little, used with permission) Figure 37. Conidiophores and conidia of Cladosporium sp. (photo by C. Little, used with permission) Author is copyright owner and grants permission for image to be used. 38 Figure 38. Rock lichens forming black apothecia (photo by L. M. Carris, used with permission) Author is copyright owner and grants permission for image to be used. 39 Figure 39. Lichen (Cladonia sp.) forming orange-red apothecia on stalks called podetia. (photo by L. M. Carris, used with permission) Figure 40. Development of clamp connections in basidiomycete hyphae. Each hyphal cell is dikaryotic, containing a pair of compatible Author is copyright owner and grants permission for image to be used. 37 40 From Fundamental Fungi, APS Press, used according to License conditions. Author is copyright owner and grants permission for image to be used. Author is copyright owner and grants permission for image to be used. nuclei, and this condition is maintained by the formation of the clamp connection. (image by L. M. Carris, used with permission) 41 42 43 44 45 46 Figure 41. Clamp connection as seen under microscope. (photo by L. M. Carris, used with permission) Figure 42. Dark, thick-walled, teliospores of Tilletia sp. (photo by L. M. Carris, used with permission) Figure 43. Dark, thick-walled, two-celled teliospores of Puccinia asparagi. (photo by L. M. Carris, used by permission) Author is copyright owner and grants permission for image to be used. Figure 44. Common corn smut (Ustilago maydis) galls produced on corn ears (A), tassels (B), midrib (C), and leaf sheath above the brace roots (D). (photos by C. Little, used with permission) Figure 45. Wheat kernels converted to bunt balls by Tilletia caries (common bunt of wheat); the fungus fills the seeds with masses of dark, powdery teliospores. (photo by L. M. Carris, used with permission) Figure 46. General life cycle for a macrocyclic, heteroecious rust. Red arrows indicate production of spermatagonia (of both mating types) on the upper surface (upward arrow) of the aecial host leaf, whereas aecia are produced on the lower surface (downward arrow) of the aecial host leaf. Haploid (n), dikaryotic (n+n), and diploid (2n) phases of the life cycle are denoted by thin, double, and thick lines, respectively. The Author is copyright owner and grants permission for image to be used. Author is copyright owner and grants permission for image to be used. Author is copyright owner and grants permission for image to be used. Author is copyright owner and grants permission for image to be used. Author is copyright owner and grants permission for image to be used. 47 dashed line indicates separation of the aecial and telial hosts as is required to complete the life cycle of heteroecious rusts. Thus, aeciospores from the aecial host infect the telial host to produce uredinia (in a macrocyclic rust), and basidiospores (of both mating types, denoted in red and blue) from the telial host infect the aecial host to produce crossfertile spermatagonia so that the dikaryon may be reestablished. (image by C. Little, used with permission) Figure 47. Black stem rust of wheat, Puccinia graminis var. triciti. Uredinial stage on wheat stems. (photo by X. Chen, used with permission) Email permission obtained from X. Chen, USDA ARS, Pullman WA 48 Figure 48. Puccinia graminis var. Email permission obtained from X. Chen, tritici, aecial stage on abaxial side USDA ARS, Pullman WA of barberry (Berberis sp.) (photo by X. Chen, used with permission) 49 Figure 49. General life cycle for a basidiomycete. The red arrows indicate the hymenium of a basidiocarp where basidia are located and basidiospore development occurs. Although only mushroom-like and bracketlike basidiocarps are shown, many other types exist, but have the same function. Haploid (n), dikaryotic (n+n), and diploid (2n) phases of the life cycle are denoted by thin, double, and thick lines, respectively. (image by C. Little, used with permission) Author is copyright owner and grants permission for image to be used. 50 Figure 50. Example of mushrooms (photo by L. M. Author is copyright owner and grants permission for image to be used. 51 52 53 54 55 56 Carris, used with permission) Figure 51. Puffballs growing on rotting log (photo by L. M. Carris, used with permission) Figure 52. Fomitopsis pinicola, a common shelf fungus in the U. S. Pacific Northwest (photo by L. M. Carris, used with permission) Figure 53. Dictyophora duplicata, a skirted stinkhorn. Spores are in the brown slimy mass at the apex; the smell of rotting flesh attracts flies and other insects, which pick up the spores on their bodies and hence facilitate spore dispersal. (photo courtesy of T. J. Volk, Fundamental Fungi, APS Press) Figure 54. Brown, gelatinous fruiting bodies shaped like human ears give Auricularia auriculara its common name, the ‘Wood Ear’ fungus. A related species is cultivated and widely used in Asian cuisine. (photo by L. M. Carris, used with permission) Figure 55. Orange, gelatinous fruiting bodies of the jelly fungus Dacrymyces palmatus growing on wood (photo by L. M. Carris, used with permission) Figure 56. Fruiting bodies of two common birds nest fungi, Crucibulum laeve (left) and Nidula niveotomentosa (right). Basidiospores are formed inside the peridioles (lozenge-shaped structures inside the cups); the peridioles are splashed out of the cups by drops of rain. The basidiospores are released when the peridioles decay or are eaten by insects. (photos by L. M. Carris, used with permission) Author is copyright owner and grants permission for image to be used. Author is copyright owner and grants permission for image to be used. From Fundamental Fungi, APS Press, used according to License conditions. Author is copyright owner and grants permission for image to be used. Author is copyright owner and grants permission for image to be used. Author is copyright owner and grants permission for image to be used. 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 Figure 57. General zygomycete life cycle. Plasmogamy, karyogamy, and meiosis are highlighted. Haploid (n), dikaryotic (n+n), and diploid (2n) phases of the life cycle are denoted by thin, double, and thick lines, respectively. (image by C. Little, used with permission) Figure 58. Sporangiophores and sporangia of Rhizopus stolonifera. A characteristic of this fungus is the formation of dark, root-like rhizoids at the base of the sporangiophore. (photo by L. M. Carris, used with permission) Author is copyright owner and grants permission for image to be used. Figure 59. Sporangiophores of Pilobolus sp. developing on horse dung in laboratory. (photo by L. M. Carris, used with permission) Figure 60. Closeup of sporangiophores and sporangia of Pilobolus sp. The sporangiophores are growing towards a light source. The dark, cap-like sporangia are explosively shot off when the swollen apical portion of the sporangiophore ruptures. The sporangia can travel over 3 meters before landing on a substrate. (photos by Marco Hernandez-Bello, used with permission) Figure 61. Plasmodium (photo by S. Stevenson, used with permission) Author is copyright owner and grants permission for image to be used. Figure 62. Colorful sporophores of slime mold. (photo by S. Stevenson, used with permission) Figure 63. Bright yellow plasmodia of Fuligo septa such as Email permission obtained from Steven Stevenson, Univ. of Arkansas Author is copyright owner and grants permission for image to be used. Email permission obtained from Marco Hernandez-Bello, Univ. California-Davis Email permission obtained from Steven Stevenson, Univ. of Arkansas Author is copyright owner and grants permission for image to be used. 64 65 66 this one can appear overnight in landscaping beds. (photo by L. M. Carris, used with permission) Figure 64. Sporophore of Fuligo septica developing on woodchips in landscaping (photo by L. M. Carris, used with permission) Figure 65. The club root pathogen Plasmodiophora brassica causes host roots to become grossly swollen as with this infected broccoli plant. (photo courtesy of R. N. Campbell, Fundamental Fungi, APS Press) Figure 66. Spongospora subterranean causes powdery scab of potato, so-named because of the scabby-appearing lesions that form on infected tubers as seen in this picture. (photo courtesy of W. J. Hooker, Fundamental Fungi, APS Press) Author is copyright owner and grants permission for image to be used. From Fundamental Fungi, APS Press, used according to License conditions. From Fundamental Fungi, APS Press, used according to License conditions.