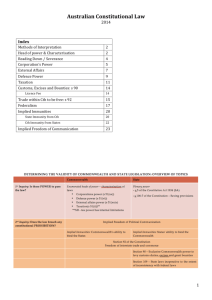

LAWS 2150

advertisement