the case of the project method (1918-1939)

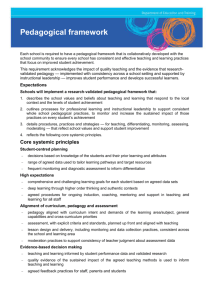

advertisement