Structural Analysis of Housing Remodeling Industry

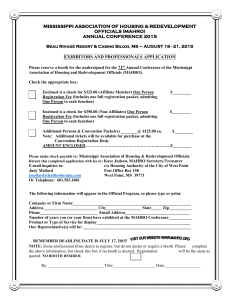

advertisement

A Losing Brown Field, Recolored Or Reshaped? Yee-Chaur Lee, Lih-Horng Chen1 Abstract Brown field in most of the developing countries are competing with time and tide nowadays. As competitors all over the world advance with hi-tech industries, brown field in old industrial area has situated in a dilemma while its competitive advantage can no longer be maintained. As worldwide competitions become more intense and immediate, old industrial areas, which are aimed by the government to enhance their competitiveness, may pursue to the redevelopment strategies including land use rezoning (recolor) and production revitalization/innovation (reshape). This article, mainly deals with brown field that normally cannot develop its competitiveness, is aimed to establish a mechanism for sustainable advantage of which a losing brown field may compose as capacities. A qualitative model is formulated to specify the critical point where reshape and recolor is split based on the land use intensity and thereby land use tax. Please be noted that some research spots proposed herein are seen from the authors’ view as a request for further comments and suggestions rather than being treated as conclusions to this article. Keywords: brown field, land use plan, land use tax, urban redevelopment, Laffer curve, critical point, innovation Were Industrialization and Urbanization Attributed to the Brown Field? Ever since the industrialization of modern cities in the late 19th century, cities were rapidly changed with production and population patterns. Farming was replaced with manufacturing whereas land use intensity was rapidly changed and upgraded. It is common that the more industrialized a city, the predominant the urbanization it is (Chen, 2002). As manufacturing industries grow and acquire more land, population and income normally increase simultaneously. Consequently a city expands with industries of diversity shown as Table 1. This table shows the different transformation patterns of industrialization along with the enhancement strategies on the corresponding time-frame stages. The “production chain” is found to tie up with the “income and population level” within a city. Confronting with the world tides of swift production patterns, traditional manufacturing industries within inner cities or isolated 1 Yee-Chaur Lee, Chung Hua University, Hsinchu, Taiwan. Email:joeychuc@yahoo.com.tw. O:03-5186651, Add: 707 Wu-Fu Rd. Sec.2, Chung Hua University, Hsinchu 300, TAIWAN. Lih-Horng Chen, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan, TAIWAN. 1 industrial parks have been losing their competitive advantages. Internal enclaves were found in old industrial areas and thus “brown fields” were found. Table 1 Industrialization Development Process and Enhancement Strategies Industry Pattern Transformation Industrialization Development Process Factory Initiated Farming with Light Industry Farming with Manufacturing Industry Enhancement Strategies Farming support industry Cities support industry Individual production unit Development without regulation or planning Factories Established Factories Clustered Intensive Labor Industry Manufacturing Mixed with Residential/Urban sprawl Industry agglomeration Planning mechanism Land use restrictions Industrial District Import Replacement Industry Over Developed / Environmental Concerns Hardware framework enhancement Zoning Decentralization Industrial Park Heavy and High Tech Industry Transformation of Industrial Area Software framework enhancement Zoning regulation Function improvement Sustainable Park Knowledge-based Economy Industry Demand diversified Large-scale land needed Redevelopment of Old Industrial Area Industries for Sustainability Coordination Revitalization Innovation Ever since the Ruhr area in Germany was successfully transformed by IBA and made itself a world famous revitalization project, brown field became an issue that 2 attracts the spotlight of planner from private and public sectors. Accompanied with old residential area in a city, brown field becomes an issue of urban infill. Brown field can be classified by its definition and formation. It implies to the area where previously developed, normal production decreasing or ceased, land use less intensive, and business downwardly reversed. It may be located around the periphery of or inside the city, and very often the existing industrial infrastructures are deteriorating or not in current use. Brown field may therefore include abandoned railway, station, factory, wharf, housing, and industrial facilities. All of which, as Roger Trancik (1994) put, are seen as “lost spaces” in today’s city. For the improvement of lost spaces, theoretically the “figure-ground”, “linkage”, and “genius loci” are proposed as planning and urban design strategies for urban redevelopment (Tancik, 1994). Diagram 1. Definition and Scope of Brown Field Previously developed Rural and urban (location) Land and / or buildings Is Not in current use Brown Field Land contamination Partially occupied May Be Vacant Statutory contaminated land Derelict Green Belt Sandra, Victoria, Peter and Nathan (2000) The Definition of Brownfield Given that brown field may make city space fragmented and malfunctioned, the redevelopment of brown field and old industrial area is normally treated by articulation of urban function for sustainability. With diverse modes of production, articulation is a conjuncture of large-scale society strengths: specific time frame along with space configuration and industry formation. As brown field may be a reflection of industrialization and urbanization process, the redevelopment strategies that would apply to the old industrial area may not simply the issues of industry transformation and environment protection. Instead, it would be pursed from the perspective of urban function with articulation on economy, society, and civilization. Brown field, which turned out to be lost space as Trancik put in “Finding Lost Spaces”, becomes a place where previous urban function nowadays has deteriorated. However, these areas, from the authors’ viewpoints, are the places where the advantage of proximity to the center and the accessibility to the resources from existing periphery is maintained. The goals 3 for the redevelopment of brown field may include but not least to protection, revitalization, preservation, and therefore the comprehensive amenity of a city. Diagram 2. Goals For Brown Field Redevelopment Environmental cleanup & protection Neighborhood revitalization Brownfield Redevelopment Tax base growth utilization of existing infrastructure Green space preservation Civilization revival Job creation Sandra, Victoria, Peter and Nathan (2000) The Definition of Brownfield Literature Review On Regional Development Differences Brown field redevelopment issues have been reviewed from variety of perspectives. For years many studies have investigated spatial differences in old industrial areas of economic and urban redevelopment (Gehrke and Legler 2001, European Commission 2003). Some of the viewpoints are recognized: ‧ Old industrial areas have been identified being less innovative thus less productive. A focus is placed on incremental and process innovation due to a pre-dominance of mature industries and externally controlled firms (Tichy 2001). ‧ One concentrated industry area would be helpful for the spill over of technology, and the effect of redevelopment and innovation can be spread over to the nearby areas. To incorporate the benefits of innovation, reinvestment can enhance the R&D capacity of a firm, and thus incorporate the external benefit internalized. (Romer, 1986) ‧ Research activities are usually highly concentrated in larger agglomerations (Gehrke and Legler 2001, Simmie 2003) whereas brown fields were commonly clustered around the heavy industrial metro areas such as Chicago, Pittsburgh in the US (General Accounting Office, 1995). ‧ Competition, specialization, innovation can promote the industry growth and the competitiveness of an industry, whereas diversification would relieve the stress for innovation (Glaeser et al, 1992). ‧ Jacobs (1966) reminded us that technology improvement would shift and spread among the industries, which would enhance the growth and innovation of the industries. Competition and diversification would be helpful in maintaining the 4 competitiveness of an industry whereas specialization would to the contrary hamper them. ‧ Whether or not specialized or diversified agglomerations are conducive for industrial redevelopment. Porter (1998) argued for innovation advantages of specialization, while others state diversification is more favorable. From the viewpoint of dynamics of a city history, industries developed accompanied with a city. City by its nature is a place affluent with information, capital, population, and commodities. Due to its comparative advantage of proximity and locality, the land rent and economic activity are usually much higher and active. This explains the spillover effect of industry agglomeration. As an old industrial area gradually loses its competitiveness, and if a redevelopment stitch cannot be made in time, there finally we will see an “in-piece” city with inner decay. The main characteristic of many industrial institutions on periphery is that urban redevelopment prerequisites are constructed weakly as there is a lack of dynamic clusters and of support organizations. In these old industrial areas, industrial activities are generally at a lower level in comparison to more central and agglomerated areas (EC 2003). This does not rule out the possibilities that there are innovation and productivity prevailing in such areas, but often the critical mass for a dynamic cluster development is not reached. If there are clusters in the brown field, they are often in traditional industries with little R&D and innovation activities. Whether or not brown field may therefore dwells upon a critical point where reshape with innovation or recolor with rezoning based on the industrial thickness. That deals with the locality of “center and periphery” that each brown field may inherit from urban economy and geography viewpoints. Center vs. Periphery on the Redevelopment of Brown Field A city can be perceived as a center/periphery dichotomy where the center has a level of dominance over the periphery, which is reflected in business intensity, population, transportation, and land use pattern. Accessibility is higher within the elements of the center than within the periphery and most of the high-level economic activities and innovations are located in the center. This pattern was particularly prevalent in the pre-developing countries which favored the accessibility of the center to resources and markets of the periphery, a situation that endured until 1970s. In between the center and periphery of a city, the semi-periphery has a higher level of autonomy and has been the object of significant process of economic development in the countries with rare resource of land. The accessibility of the semi-periphery improved, permitting the exploitation of its comparative advantages in labor and resources. The problem regarding center and periphery is emphasized on incremental 5 innovation system. The low level of productivity does not only hamper the internal innovation activity in a region, rather it leads to a low absorption capacity of the industrial institutions. The low level of industry clustering and agglomeration implies an “anti-thickness” and less specialized structure of knowledge suppliers (Todtling 2003). Knowledge spillovers can be observed in industrial clusters and agglomerations, and they are constrained to a certain geographical distance from the centers (Baptista 2003). As Feldman (1994) and Fritsch (2000) pointed that peripheral regions are regarded as less innovation in comparison to agglomerations because of less R&D intensity and lower shares of product innovations. Old industrial regions and industries represent another type of problem area where learning and innovation has been insufficient, despite of efforts of renewal in recent years (Rehfeld 1999, Todtling 2003). In contrast to peripheral regions, where the lack of clusters appears to be an important development barrier, old industrial regions face the opposite problem of too strong clustering as crowded with mature industries experiencing decline (Tichy 2001). These regions have been confronted with the negative issues of clustering which leads to a loss of regional competitive advantage and innovation capacity. This can/could be observed in areas hosting heavy industries like Ruhr area in Germany, Wales in UK, Pittsburgh waterfront in US, Kobe seashore in Japan, Pusan harbor in South Korea, Taipei metro in Taiwan and the others in the world. Old industrial regions often have a highly developed and specialized knowledge generation and diffusion system. What appears to be problematic is that it is usually oriented on the traditional industries and technology fields (Cooke et al. 2000). The analysis of the main redevelopment barriers of old industrial regions shows that there is no single best practice policy approach addressing the problems and the challenges. A general view of redevelopment process is seen as being essential when it comes to formulate political initiatives adequate to foster learning process. This means that focusing only on technological aspects of redevelopment strategies is often not enough (Cooke and Memedovic 2003). They, according to Cooke, should be dealt with organization, financing, education and innovation techniques. Redevelopment can be well processed with physical capital such as R&D and technology infrastructure, human capital (training of employees) and social capital, namely the formation of trust-based relationships between regional actors (Nauwelaers 2001). Competitive Forces of Brown Field With respect to the relational assets of old industrial areas, it was found that a key feature of these regions is that they suffer from various forms of “lock-in” (Grabher 1993), which seriously curtail the development potential and innovation capabilities. Analyzing the adaptation and innovation problems of the Ruhr area, Grabher (1993) 6 identified “lock-ins” on the respect of function, cognition and politics. It was observed that too rigid inter-firm networks, homogenization of worldviews, and strong symbolic relationships between public and private key actors hampering industrial restructuring. Phenomena like these have been observed in many old industrial areas worldwide. In general, metro areas are regarded as centers of innovation, benefiting from scale economies and agglomerations. However, not all metro areas are such centers of productivity. Despite these areas usually have highly developed organizational infrastructures of innovation, the problem of lack of networks and interactive learning seems to represent an important innovation barrier in such areas. As a consequence, the development of new technologies and industries as well as the formation of new firms are often below expectations. This phenomenon can be derived from the old industrial areas depending upon the locality of center and periphery. The main policy agenda usually is the strengthening and upgrading of regional economy. For old industrial areas, redevelopment policy should give priority to organizational and technological “catching up learning”. The target efforts may include the introduction of up-to-date management technique, product and process technologies enhancement, and organizational restructuring and practicing. To reshape the old industrial firm with support of formation and enhance the redevelopment/innovation capabilities of existing companies can be important (Todtling & Trippl, 2002). In many cases such as the Ruhr area in Germany and the Bay area in the US, an approach combing endogenous and exogenous elements seems to be workable. This includes linking regional old industries to new business partners and knowledge sources both inside and outside the periphery of old industrial areas. Development measures for old industrial areas should be strategically oriented on facilitating the renewal of the regional economy. Redevelopment policy in this context is encouraging transition to new fields and trajectories and stimulating product and process innovations for new markets. In the old industrial area, core issues for redevelopment include both the restructuring/revitalization of old industries and the development of clusters in new or related industries or technologies (Todtling and Trippl 2004). As Cooke put in 1995, there is little evidence so far that old industrial areas can “leapfrog” successfully into high tech sectors. Instead the “reshape” strategies may support the diversification and modernization activities of existing firms and the formation of new enterprises. However, such an endogenous approach may often not be sufficient to foster structural change in old industrial regions. Therefore, the feasible strategies for redevelopment should move to attract more foreign direct investment bringing complementary knowledge to the “reshape” clusters. The brown field and city redevelopment interaction circle is shown below on diagram 3. The impacts of the existing brown field on city, both on economy and 7 environment, may include externality and income decrease, which in the long run would affect the livability of a city. Diagram 3. Brown Field and City Redevelopment Interaction Circle ECONOMY productivity deterioration cost adjustment economy decline income decrease Brown Field society conflict Livability security issues City externality pollution & contamination space capacity energy I/O & waste ENVIRONMENT A Trial Empirical Study – Brown Field at Hsinchu Taiwan To identify the issues of redevelopment in brown field, the authors hold a survey on Hsiangshang Industrial Park (HIP) at Hsinchu Taiwan, where host mostly traditional manufacturing firms. The results show that more than 40% of the factories are vacant or abandoned, which suits HIP a brown field and needs account of either recolor for rezoning or reshape for regeneration. It is realized that more than 40% of the respondents unsatisfied with the current situations of the Park. Amongst the “lack of comprehensive planning” is mostly complained. Respondents agree that “rezoning” and “tax relief” are two effective measures for brown field redevelopment. Meanwhile around 60% of the respondents believe that the HIP has contributed to the local economy, would it be continued for manufacturing use. However, being asked for rezoning, about 70% of the respondents stand for “commercial” and “residential” with higher intensity land use. Given the existing facilities at HIP may not meet the needs of the firms, there are 70% respondents who are satisfied and confident with the 8 current business situation. As a whole, more than 80% of the respondents would stay at the Park and maintain business. Around 30% of the firms say that they would increase investment in HIP for the coming 3 years. Being asked what would be the considerable ingredients for effective production auras, “employee quality”, “transportation convenience”, “production machinery”, “government mechanism”, and “financing institution” are amongst the priority selections. It should be noted that about 90% of the respondent firms hiring less than 50 employees, 83% of which claiming its annual business turnover less than 50 million NT dollars (approximately 1.4 US dollars), which is about equal to the registered capital volume2. The result of this survey considerably fits well with the current situation in today’s brown field in Taiwan. It should be noted that the majority of the manufacturing firms in old industrial area in Taiwan is normally belonged to the “small business”, which hires lesser employees with smaller business volume and least R&D activities. They are usually clustered by business train and vulnerable to the fluctuations of foreign currency exchange and domestic economy. As the competitiveness of the firms are no longer existed, business will be forced to close waiting for recolor or to reinvest for reshape. Some research studies suggest there are three different dimensions to the cluster concept, related to space, business function and government policy. Making explicit distinction between these three dimensions may contribute to the dynamics of spatial issues in old industrial areas. Turning to the case of the traditional manufacturing industry at HIP Taiwan, there is a stronger emphasis on clusters as sets of functionally interrelated industries and supporting institutions (Lee 2003). This allows for the analysis of relations and other interdependencies across industries that may be important for identifying the sources of competitive advantage but not necessarily fit into a spatially defined territorial system. Then the problem rises: on what critical point would the firms in an old industrial area would pursue to the different brown field redevelopment strategies, reshape or recolor? Nevertheless, it is not necessarily to say that the preceding survey and situation analysis would apply worldwide. To adopt an explicit cluster strategy seems to be a crucial step in this context. Relevant policy actions are to identify newly emerging regional complexes of related industries, which have a strong local knowledge base in the region and to promote their growth and dynamic development. In order to enhance the synergy potential in old industrial areas and to improve international visibility measures directed towards redevelopment, complementary activities that both private and public sectors can exert for the best interests for the region are strongly recommended. 2 This survey was undertaken in May 2004 and sponsored by Hsinchu City Government. Totally 62 out of 166 existing firms were interviewed. More details can be referred upon request. 9 Critical Point for A Brown Field to Recolor or Reshape Spatial analysis related to the industry development is a central area of research for planners. It deals with core concepts in economy and geography, as the role of space for industrial location and transformation is frequently discussed. It seems to be a commonly held opinion that our understanding of the causes and economic impact of spatial analysis still limited or at least not crystal clear. There is one question that should be considered in the old industrial areas: what has to do with the difficulties concerning empirical validation of the advantages of recolor or reshape? Theoretically some spots from economics can be applied for this concern. The critical point for a brown field to recolor or reshape is compared to the situation that at this point, there exists no difference either for recolor or for reshape. It is commonly pursued by the firms that the purpose for business activities is aimed for maximization of the benefit, namely the bottom line. Taking the whole old industrial area, the total productivity and the benefit normally would be maximized if only if the bottom line of each individual hits the ceiling. Despite the land use pattern may in some sense change the land use intensity, an old industrial area can be evaluated by the critical point where the marginal utility of manufacturing equals to the marginal utility of non-manufacturing (usually residential and commercial). This implies that a “parabolic” curve with a maximization value of reflection point can be attempted to formulate. Given that the land use plan is an independent valuable, the business totality can be seen as a dependent variable that would change with land use plan3. Presumably, the authors reviewed some of the articles that would basically fit the preceding situation. Given that the preposition of marginality and the fact that land use pattern and intensity is somewhat paralleled to the land use tax rate, Laffer curve is adopted for transformation. Because of its explanation ability on the cause and effect of the variables, the structure of Laffer curve can be reformed and incorporated with reshape and recolor issue. Laffer curve4 is a curve which supposes that for a given economy there is an optimal income tax level to maximize tax revenues. If the income tax level is set below this level, raising taxes will increase tax revenue. And if the income tax level is set above this level, then lowering taxes will increase tax revenue. Although the theory claims that there is a single maximum and that the further one moves in either 3 For the purpose of analysis simplicity, the authors would instead propose a more generalized prototype of parabolic, which needs more empirical examination with reliable data and details. 4 The Laffer curve is aptly named after Professor Art Laffer, an former advisor to President Reagan in the early 1980s. Laffer and other right-wing economists used the curve to argue that taxes were currently too high and should therefore be reduced to encourage incentives and harder work. 10 direction from this point, the lower the tax revenues will be. In reality this is only an approximation. The Curve suggested that, as taxes increased from fairly low levels, tax revenue received by the government would also increase. However, as tax rates rose, there would come a point where people would not regard it as worth working hard. This lack of incentives would lead to a fall in income and therefore a fall in tax revenue. The logical end-point is with tax rates at 100% where no one would bother to work and so tax revenue would become zero. Thee Laffer curve is illustrated below: Diagram 4. The Laffer Curve Tax Revenue Tx tax rate (%) T* represents the optimum tax rate where the maximum amount of tax revenue can be collected. One might think that doubling the tax-rate would double the taxation revenue. Mathematically it is true, but this is not so in reality. As tax-rate increases, people just choose to quit, because it is not worth their while. This is called dead-weight loss. If we introduce a tax and increase it slightly from very low tax rate, taxation revenue normally increases. But if the tax rates are already very high and increased, the tax revenue raised by the government actually goes down, because of the “drop-out” from the trading system. It takes a number of forms, such as leaving jobs and drawing welfare, or making things at home for free tax. There is a point on the Laffer curve at which the taxation revenue is maximized. At this point the government actually reduces its revenue either by increasing or decreasing tax-rates. The dead-weight losses at the Laffer curve maximum are beyond expectation. Once a government hit the Curve maximum, taxpayer would pay the ever most taxes if they cannot be aware of this situation (ie. they are locked in instead of drop out). Then government cannot raise more tax revenue. It must either get by with what they already have, borrow money, or increase the country's income. At this point, dynamic optimization between tax rate and tax revenue is reached. The Laffer curve simplified a situation that the tax revenue is the consequence of articulate manipulation of government. The authors then further examine the concept of Laffer curve and find that to address the problem of brown field, the structure of the curve may be transformed as such. Details follow. 11 Diagram 5. Genres of City Development Donought City (center decay) land use intensity (%) Dumpling City (center clustering) (%) center distance to the center (%) As a city is a reflection and a consequence of the industry development, land use intensity may dominate the pace and pattern of a city. There are two typical genres that can be classified based on the development intensity of center. The majority goes with the “dumpling city”, where the more close to the center, the higher land use intensity it will be. However, a “donought city” goes reverse, in which inner city decay is detected. Given other things being constant, the strategy that a brown field may pursue for redevelopment would depend on the genre and the locality that can be measured by the distance to the center. From diagram 5 we learn that the land use intensity is comparatively high in a “dumpling city”, where spatial clustering and agglomeration would occur around the center. To the contrary, a “donought city”, which is not quite common, represents an industrial thinness around the center and in some sense implies a phenomenon of urban sprawl with inner city decay. Diagram 6. Development Intensity vs. Land Use Tax Rate Decreasing development intensity Cx land use tax rate decreasing from the center This diagram represents the land use intensity along with land use tax rate decreasing from the center, where C* has the highest land use intensity and land use tax. Given that the land use tax rate is positively compared to the distance to the center5, the first major assumption in this article, we can redraw diagram 5 to diagram 5 In this paper, only the city development lands are considered, not including the green land and agricultural area. Besides, only the “dumpling city” is considered since the “donought city” is not 12 6. This stands quite natural. Wherever there is no development intensity, there should be no tax. It should be noted that the development intensity is somewhat in relation to the land use intensity, which is normally represented by floor area ratio (FAR) and/or building coverage ratio. The second major assumption in this article is that the business amount is directly or indirectly confined to the land use (or development) intensity. We may as well derive diagram 7 from diagram 6. It should be noted that for an old industrial area, if the land use intensity is lower than the critical point (as C denoted in the diagram), the reshape strategy is pursued whereas land use intensity is higher than C, the recolor strategy would apply. However, this critical point, like the optimal tax rate in Laffer curve, is not easily identified in practice. It varies and is confined with the other elements beside land use tax rate. Nevertheless, the development intensity is specified within a land use plan, which is a tool that can be manipulated by the government. This implies that, if other things being equal, to manipulate the land use intensity up to the critical point may offer the firms in brown field an opportunity to select “reshape” or “recolor” for redevelopment. Diagram 7. Business amount vs. Land Use Intensity business amount (tax revenue) Reshape Recolor C land use (development) intensity The advantage of this measure is that each individual firm may determine its goal out of its best and maximum interest. In other word, at this point there would be two alternatives that would bring forward the same business amount. However, it should be noted that the tax revenue collected from the firms may not be the same as either a reshape or a recolor strategy is pursued. “Government subsidy” tells the difference6. That is a quite common strategy in the countries where the so-called “hi-tech” are regarded as prime industries. However not every firm in a brown field has the commonly perceived. 6 Some countries offer tax reduction mechanism, such as intended low corporate tax rate, by endowing the hi-tech firms with tax subsidy. Therefore the taxable corporate income differs between diverse industries. 13 capability to select, let alone advance itself up to the “hi-tech club”. It should be noted that if the willingness and preference is against “reshape”, then the selection is limited. The buck is back to the government: the critical point should be manipulated either by lowering the tax (from diagram 6) or increase the development intensity (from diagram 7). Be reminded that as utility maximization is pursued at the critical point and is based on the self-interest of each activist, other things being equal, the redevelopment strategy that a firm in a brown field would pursue would formulate an indifference curve below. At this point, there it makes no difference whether reshape (innovation) or recolor (rezoning) is pursued. However, the total utility can be increased on the condition that the curve itself is move outwardly (utility curve II). What would constitute the strategies that will feasibly push out the curve to increase the utility? The redevelopment of a brown field is not only an economic issue but also a social problem. Whatever strategies may pursue, that would simultaneously deal with from the perspectives of economy, environment, and society. For the purpose of brown field redevelopment, the empirical study at HIP and the qualitative model suggest “tax relief” may be one of the feasible measures7. The government may make changes in tax for a number of reasons. A Keynesian government may choose to vary the level of tax to try to influence the level of aggregate demand and therefore economic growth. A Classical government would view the role of tax as an instrument very differently. It would argue that taxation should be as low as possible to create incentives for people to work harder. Low tax should be encouraging firms as they will not lose much of the profit in taxation. One point needs our consideration is that what would in reality a firm would be benefit should there be a critical point? Or what would in reverse affect a firm if this point does not exist or hard to be set or detected? Diagram 8. The Indifference Curve at the Critical Point reshape (innovation) utility curve II utility curve I 0 7 recolor (rezoning) In practice, many governments will use taxation in a combination of these two ways and will formulate their policy to fit the prevailing condition. 14 Brown Field Redevelopment Guidelines The redevelopment of brown field is getting more attention from the public sectors. It is found that the regional economy, job opportunity, environment quality, greenbelt preservation would be hampered if the situation worsens. What would be the strategies that a losing brown field can apply to compete for redevelopment rezone or/and reshape? Brown field redevelopment is an issue of public domain. One of the key actions is to introduce the resources from the NPO/NGO. With the assistance from these groups, the interested parties may reach consensus than it otherwise without. Meanwhile, the public sector is encouraged to prepare the strategies and guidelines for redevelopment including: 1. Highlights the contaminated and deteriorated areas where are prioritized for redevelopment purpose; 2. Recognizes the brown fields where the private sectors may be of interest on redevelopment; 3. Detects the catalyst districts where may be of redevelopment paradigm; 4. Improves the brown field where would create job opportunity; 5. Exerts the spillover effect that would maximize the public welfare. The knowledge economy and innovation have moved to the foreground both in regional and industrial policies in the past decade. This paper takes differences into account by analyzing the strengths and weaknesses of old industrial areas where redevelopment approach may fail in “organizational thinness” and “fragmentation”. Old industrial areas often have combinations of reshape (innovation) and recolor (clustering) barriers. The main problems are the low level of R&D and productivity due to a dominance of “lock-in” in traditional industries, weakly developed firm clusters. Critical thresholds for innovation networks for reshape are very often not reached. For the purpose of reshape, external firms should be focused to embed them into the old industrial areas. They are encouraged to link to the outside clusters and resources providers, which would in the long run construct the “multi-mode park”, where urban functions of livability can be enhanced. In old industrial areas, there are many firms and dominant clusters, which are too often oriented on old industries and hi-tech perspectives. The challenge lies in the business and policy networks. For the purpose of reshape, the old industrial areas should focus on the reorganization of firms and networks, the attraction and generation of new firms, and the establishment of research institutions. The key issue then comes to how to stimulate more innovations and development of new industries, which should be related to the existing industries. The proposals outlined in this paper should be considered as basic guidelines for the preparation of a more differentiated redevelopment policy approach. Each old industrial area should further develop and 15 adapt these strategies to its own circumstances. In order to formulate and implement redevelopment actions, planners must possess a detailed knowledge on the critical point where old industrial areas would pursue for reshape (innovation) or recolor (rezoning). Conclusions This article attempts to bring out the issues and redevelopment strategies of brown field where current situation is no longer productive and friendly. Based on the structure of Laffer curve, the authors propose a similar diagram with a critical point where the “reshape” and the “recolor” strategies make no difference. A firm in a brown field can thus determine the strategies that would benefit most theoretically from the diagram. This paper is by no means a final conclusion. Instead it needs more effort on quantitative analysis and empirical study for this concern. Without any doubt, this article requires more in depth research. Therefore the authors would be more than glad to receive any comments regarding the methodology and framework of this article. References 1. Baptista, R., Do firms in clusters innovate more?, Research Policy, 27, 1998. 2. Cooke, P., Knowledge Economies. Clusters, learning and cooperative advantage, Routledge, London, 2002. 3. Cooke, P. & Memedovic, O., Strategies for Regional Innovation Systems: Learning Transfer and Applications, Policy Papers, UNIDO, Vienna, 2003. 4. Doloreux, D., What we should know about regional systems of innovation, Technology in Society, 24, pp.243~263, 2002. 5. European Commission, 2003 European Innovation Scoreboard: Technical Paper No3 Regional innovation performances, EC, Brussels, 2003. 6. Feldman M. & Audretsch, D., Innovation in Cities: Science-based Diversity, Specialization and Localized Competition, European Economic Review, 43, pp. 409~429. 7. Grabher, G., The weakness of strong ties: the lock-in of regional development in the Rhur-area, The embedded firm: on the socioeconomics of industrial networks, T.J. Press, London. 8. Kaufmann, A. & Todtling, F., Systems of Innovation in Traditional Industrial Regions: The case of Styria in a Comparative Perspective, Regional Studies, 34, pp.29~40. 9. Lundequist, P., Spatial Clustering and Industrial Competitiveness, Dissertation for Ph.D. in Social and Economic Geography at Uppsala University, 2002. 10. Morgan, K., The Learning Region: Institutions, Innovation and Regional Renewal, Regional Studies, 31, pp.491~503. 16 11. Porter, M. The Competitive Advantage of Nations, Free Press, New York, 1990. 12. Romer, Paul M., Increasing returns and long-run growth, Journal of Political Economy, 98, 1990. 13. Todtling, F & Trippl, M, One size fits all? Towards a differentiated policy approach with respect to regional innovation systems, Draft version, Paper prepared for DIW Berlin, 2004. 14. http://www.bized.ac.uk/virtual/economy/policy/tools/income. 17